A Confederate bullet strikes James Longstreet and derails a Wilderness victory.

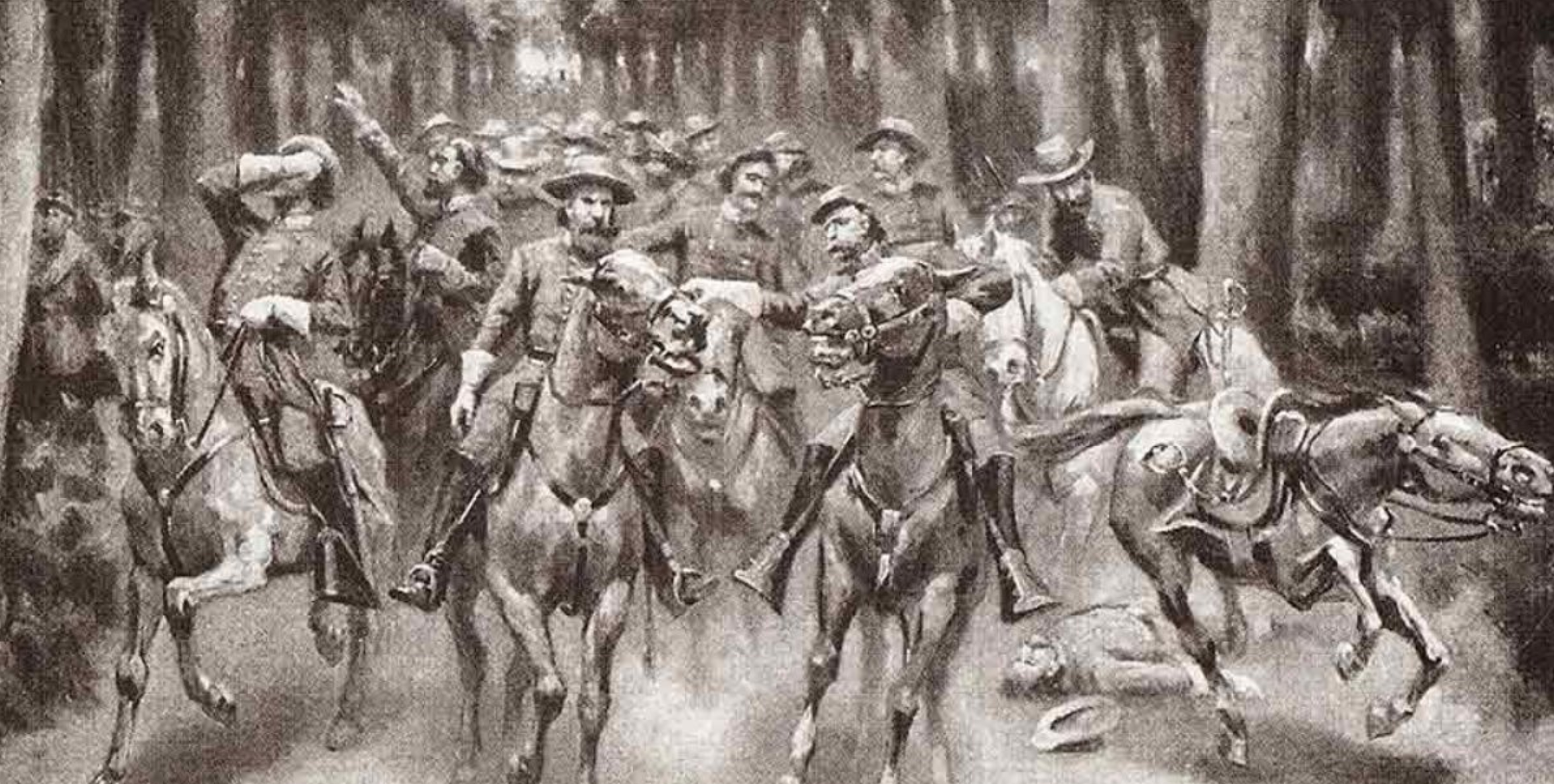

The Confederate flank attack had worked to perfection May 6, 1864, the second day of the Battle of the Wilderness. Just before noon, the men in Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s First Corps had hurtled down the Orange Plank Road, and an unfinished railroad cut, to slam into the exposed left flank of the Union II Corps. Avid to push his advantage, the general knew his men, weary from a long morning march and the fierce fighting that followed, would still do anything he asked.

Nature, however, was proving to be as much an enemy as the Federals. Many of Longstreet’s troops were bogged down and lost in the thick, confusing foliage. The general and his staff officers rode out ahead, looking for a way to further press the attack.

Suddenly bullets tore through the general’s party, fired from the woods along the road. Longstreet himself was among those hit, shot through the neck.

One year and four days earlier, about four miles away, Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, had been mortally wounded under similar circumstances. But while Jackson’s wounding is frequently cited as a pivotal event of the Civil War, Longstreet’s wounding in the Wilderness is frequently forgotten. Yet the absence of the man General Robert E. Lee called his “Old War Horse” had a more immediate impact on the battle at hand and on the Army of Northern Virginia as a whole.

When the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia first clashed May 5 in the Wilderness—70 square miles of dense second-growth forest not far from Fredericksburg—Longstreet’s First Corps had been camped in Gordonsville, some 27 miles west. The corps was the farthest away from the action that morning, and as it marched toward the fighting, the Second and Third Corps were being battered by Federal attacks.

Lee had moved his men into position along two parallel roads that ran against the flank of the Union army. The Confederates had roughly 66,000 men against Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s 123,000-man command, but the odds were evened by the terrain’s thick growth, which made maneuvering difficult for the Army of the Potomac.

The Rebels held their own on the first day of battle, but a dawn attack by the Federals May 6 threatened to overwhelm the Confederate right. Literally in the nick of time, Longstreet arrived on the field with desperately needed reinforcements. “The instant the head of his column was seen, the cries resounded on every side, ‘Here’s Longstreet. The old War Horse is up at last. It’s all right now,’” one Rebel private remembered.

This terrain was unlike any most of Longstreet’s men had experienced, as they had been detailed on a foraging mission to southeastern Virginia during the Battle of Chancellorsville the previous May.

“The ground was covered with brush and small timber, so dense that it was impossible for an officer at any point of the line to see any other point several yards distant,” said a Vermonter in the Union ranks. And the dust was “so thick as to reduce every tree and shrub to one uniform shade of gray,” remembered one of Longstreet’s staff officers, which compounded the visibility problems.

Using intelligence gathered by one of Lee’s engineers, Longstreet sent four units—George “Tige” Anderson’s and William Wofford’s Georgia brigades, along with elements of Joe Davis’ mixed brigade from Mississippi and North Carolina and William Mahone’s all-Virginia brigade—along an abandoned railroad cut that put them on the Union left flank near the intersection of the Brock and Plank roads. Longstreet’s chief of staff, Lt. Col. G. Moxley Sorrel, was assigned to lead the maneuver. He would attack in concert with a push down the Orange Plank Road by Maj. Gens. Charles Field and Richard Anderson and Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw against the center of the Federal position. By hitting the Federals in front and flank, Longstreet hoped to force them north toward the Rapidan River.

Sorrel’s flank attack, headed by the Texas Brigade and assisted by troops from Georgia, Alabama and South Carolina, drove forward “like a storm,” according to one Georgian involved. The result, recalled a Federal soldier, was a “terrific tempest of disaster.” The converging wings collapsed the Union left, sending blue-coated soldiers retreating to the north and west. Union Brig. Gen. James Samuel Wadsworth fell mortally wounded along the Plank Road while trying to rally his men.

Sorrel rode back to his commander to see what the next course of action would be. “There was a pause for some time to rest the men, to get the lines straightened, and to replenish ammunition,” Major John C. Haskell remembered. Longstreet warmly congratulated General Field, and then held a quick council with his subordinates and staff.

“Longstreet intended to play his hand for all it was worth, & to push the pursuit with his whole force,” noted Brig. Gen. E. Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s chief of artillery. Longstreet detailed another flanking force to attack the new Union position forming a few hundred yards to the east on the Brock Road. He would again launch a frontal assault to coincide with the flank assault.

Brigadier General Micah Jenkins’ South Carolina Brigade, which Alexander called one of the “best & largest” in the army, would lead the frontal assault. Having just returned from an assignment in the Western theater, the South Carolinians were “dressed in new uniforms made of cloth so dark a gray as to be almost black,” noted an observer.

Longstreet and Jenkins rode at the head of the column, accompanied by Sorrel, Kershaw, Wofford, Captain Francis Dawson and at least six others. Lieutenant Andrew Dunn, from Long – street’s staff, suggested that perhaps the general was unduly exposing himself to danger. “That is our business,” Longstreet replied.

Farther east on the Orange Plank Road, the Confederate flank attack continued to unfold. Between fierce fighting and awful terrain, Mahone’s Brigade had started to lag. “[W]e passed through marsh, swamp, and burning woods,” remembered one Virginian.

In the confusion, the 12th Virginia, which had been holding the right flank of Mahone’s Brigade, was separated from the regiment next to it. The men of the 12th had to veer around a forest fire, and then found themselves advancing along the bottom of a dip between two pieces of high ground.

With their view so obstructed, they neither saw their fellow Confederates to the left nor were seen by the re-forming Federals just 100 yards or so to their right. But ahead, across the Plank Road, the men could see scattered remnants of other Federal units. They crossed the road to do battle. Realizing they were the only unit across the road, though, the Virginians quickly “wheeled around so as to be parallel with the road,” said James E. Phillips, a member of the regiment. This would bring the 12th Virginia up out of the low ground, advancing back toward the road up the northern slope of one of the hillocks they had been skirting.

The rest of Mahone’s Brigade, meanwhile, had stopped to dress ranks and re-form. They were lined up between 35 and 75 yards to the south of the Plank Road. With the 12th Virginia absent, the 41st Virginia now held the brigade’s right flank.

As the 12th Virginia moved along the north side of the road and the rest of Mahone’s Brigade on the south side, Longstreet and his party rode right between them at the head of Jenkins’ Brigade.

Dawson recalled a jubilant Jenkins, “his face flushed with joy” at the Confederate success thus far. At Jenkins’ urging, the men “cheered lustily” for Longstreet. And then disaster struck. “In the shaded light of the dense tangle, a shot or two went off, then more, and finally a strong fusillade,” said Sorrel, who was riding next to Longstreet.

Hardly had the cheering died away, Dawson recalled, “when a withering fire was poured upon us from the woods. [Mahone’s] men supposed that the enemy were upon them. Without orders one soldier discharged his piece, and a volley was then fired by the whole line.”

“Steady, men! For God’s sake, steady!” Jenkins yelled before slumping in the saddle with a bullet wound to the head.

At that moment, Longstreet received a “severe shock from a minie ball passing through my throat and right shoulder,” he would recall. “The ball struck him on the right of the larynx, passing under the skin, carrying away a part of the spine of the scapula, and coming out behind the right shoulder,” according to a newspaper account published May 28.

Sorrel saw the bullet strike. “He was a heavy man, with a very firm seat in the saddle, but he was actually lifted straight up and came down hard,” the chief of staff later wrote.

As the 12th and 41st Virginia regiments traded fire, the color-bearer of the 12th stepped out onto the Plank Road and brazenly waved his colors over his head, “although a line of our own men, not more than fifty yards—indeed, not that far—in his front were at the time pouring a deadly fire into us,” said one 12th Virginia soldier.

Meanwhile, the leading files of Jenkins’ Brigade fell out of line and prepared to fire into the woods as well. Kershaw, who had escaped injury, dashed his horse into their ranks and, in a clear voice, called “F-r-i-e-n-d-s!” Signal officer J.H. Manning did likewise. “They…instantaneously realized the position of things and fell on their faces where they stood,” Kershaw said.

Longstreet settled back in his seat and started to ride on, “waving his left hand…to Mahone’s troops, who recognized him and stopped, horror-stricken at what they had done,” Hawkins said. But Longstreet quickly realized the severity of his wound. “[T]he flow of blood admonished me that my work for the day was done,” the general later wrote.

According to Dawson, Longstreet “who had stood there like a lion at bay…reeled as the blood poured down over his breast, and was evidently badly hurt.” Jenkins, insensible, convulsed on the ground as a friend tried to comfort him. Captain Alfred E. Doby and courier Marcus Baum were killed. A witness at the First Corps hospital later described “the white horse of Marcus Baum…trotting into camp, his neck sprinkled with the lifeblood of the gallant rider.”

Haskell, for one, believed the casualty list could have been worse. “Fortunately they fired high, or there would have been a terrible slaughter. As it was…the effect was horrible,” he wrote.

As Longstreet turned to ride back, he swooned. His staff immediately helped him dismount and laid him near the foot of a tree. “He was almost choked with blood,” Sorrel noted.

“It seemed that he had not many minutes to live,” Dawson recalled. In “desperate haste,” he rode off to the nearest field hospital and found Dr. John Syng Dorsey Cullen, the First Corps’ medical director. “I made him jump on my horse, and bade him, for Heaven’s sake, ride as rapidly as he could to the front where Longstreet was,” Dawson said.

Meanwhile Longstreet, with bloody foam bubbling from his lips, beckoned staff members to lean close. He whispered for someone to find Lee and “tell him that the enemy were in utter rout, and if pressed, would all be his before night,” Haskell remembered.

Cullen soon arrived and stanched the bleeding, and Longstreet was quickly loaded onto a litter into an ambulance. Federal artillerists, who had heard the exchange of gunfire, began to lob shells into the vicinity. “Fortunately, the shots were passing high but were nevertheless dangerous,” one observer said.

Jenkins had also received medical attention, but did not fare as well. He babbled incoherently, gray matter oozing from the wound in his forehead. Colonel Ashbury Coward, a boyhood friend, knelt down to comfort him. “Taking his hand in mind, I said: ‘Jenkins…Mike, do you know me?’” Coward recalled. “I felt a convulsive pressure of my hand. Then I noticed that his features, in fact his whole body, was convulsed.”

The downed brigadier would last a few hours before finally dying. “Jenkins was a loss to the army,” Sorrel later observed, “brave, ardent, experienced and highly trained, there was much to expect of him.” On more than one occasion, he had urged Richmond to promote Jenkins to full-time division command.

The ambulance carried Longstreet to the field hospital at Parker’s Store, three miles to the rear. “The members of his staff surrounded the vehicle, some riding in front, some on [either] side and…some behind,” said artillerist Major Robert Stiles, who encountered the group on their trek. “I never on any occasion during the four years of the war saw a group of officers and gentlemen more deeply distressed. They were literally bowed down with grief. All of them were in tears.”

When Stiles rode up to the ambulance and looked in, he noticed that Cullen had removed Longstreet’s hat, coat and boots. “The blood had paled out of his face and its somewhat gross aspect was gone. I noticed how white and dome-like his great forehead looked,” Stiles recalled.

Stiles also noted red gore that stained Longstreet’s vest. “Longstreet very quietly moved his unwounded arm,” Stiles said, “and, with his thumb and two fingers, carefully lifted the saturated undershirt from his chest, holding it up a moment, and heaved a deep sign. He is not dead, I said to myself, and is calm and entirely master of the situation.”

Soldiers lining the road, who could not see Longstreet, began to suspect the general was dead and that they were only being told he was wounded in order to hide the calamity. “Hearing this repeated from time to time,” Longstreet later wrote, “I raised my hat with my left hand, when the burst of voices and the flying of hats in the air eased my pains somewhat.”

Soon the ambulance crossed Lee’s path. “I shall not soon forget the sadness in his face, and the almost despairing movement of his hands, when he was told Longstreet had fallen,” Dawson remembered. Lee would sorely miss his Old War Horse as the battle continued that afternoon. Before being loaded onto the ambulance, Longstreet had turned over command to Field and urged him to continue the attack. Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson soon arrived, and, as the senior major general on the field, command technically devolved to him, although at that moment he had little idea of what was going on or what to do next.

Field opted to reorganize the brigades on hand. “No advance could be possibly be made till the troops parallel to the road were placed perpendicular to it,” he said, “otherwise, as the enemy had fallen back down the road, our right flank would have been exposed to him, besides…neither could move without interfering with the other. To rectify this alignment consumed precious time.”

It would be 4 p.m. before the realigned troops were ready to advance. In the meantime, Sorrel later wrote, “the foe was not idle. He had used the intervening hours in strengthening his position and making really formidable works across the road.” Union Maj. Gen. William Scott Hancock, in charge of the Federal position, later admitted that even by 3 p.m. his position hadn’t been solidified, but by 4, when the attack finally came, Hancock was ready for it. The Confederates broke through briefly but were repulsed with heavy losses.

“Could we have pushed forward at once I believe Grant’s army would have been routed, as all that part which I had attacked was on the run,” Field would write.

He wasn’t the only Confederate to hold that opinion. “I have always thought that had General Longstreet not been wounded, he would have rolled back that wing of General Grant’s army in such a manner as to have forced the Federals to recross the Rapidan,” said Walter Taylor, Lee’s chief of staff.

On May 7, Longstreet was moved to the home of his friend and quartermaster, Colonel Erasmus Taylor, before being put on a train to Lynchburg. “He is very feeble and nervous and suffers much from his wound,” observed one of the women who tended him on a stopover in Charlottesville. “He sheds tears on the slightest provocation and apologizes for it. He says he does not see why a bullet going through a man’s shoulder should make a baby of him.”

Once in Lynchburg, he stayed for a time with a relative, but Federal raiding parties made the area unsafe, so Longstreet was moved even farther south—to Augusta, Ga. Longstreet would not return to active duty until October; by that point, the army had settled in to fend off Grant’s siege of Petersburg. From there, it would be a slow, inexorable grind to Appomattox.

When Longstreet was preparing to leave on May 7, newspaper correspondent Peter Alexander noted that the general was doing remarkably well. “Gen. Lee called to see him just before he was moved,” Alexander wrote, “and when he bade him farewell and came out of the tent where his great lieutenant lay, his eyes were filled with tears.”

Referencing Jackson’s wounding the year before, Alexander added, “Heaven grant that Lee may not lose his left arm now, as he lost his right arm then!”

Alexander was hardly the only person to connect the incidents. The reaction of Alexander Boteler, an aide on the staff of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, was typical: “It seems almost impossible to prevent blunders of this kind during the excitement and confusion of a battle in such a place where…the contending forces are fighting unseen foes even when at short range and almost face to face.”

Others blamed a more sinister force. “[T]he evil genius of the South is still hovering over those desolate woods,” wrote Brig. Gen. Edward A. Perry. “We almost seem to be struggling against destiny itself.”

Longstreet, for his part, took a simpler view. In his 1896 memoir, he called the incident “an honest mistake, one of the accidents of the war.” Longstreet would never regain the full use of his right arm, and his once-powerful voice would never again rise much above a whisper.

But Longstreet’s wounding, and his subsequent months-long absence, had a profound effect on Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. “Longstreet’s fall seemed actually to paralyse our whole corps,” wrote artillery chief E. Porter Alexander.

Kristopher D. White is a historian with Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park and a licensed battlefield guide at Gettysburg National Battlefield. Chris Mackowski, an associate professor of journalism and mass communication at St. Bonaventure University, is an interpreter for Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Originally published in the May 2009 issue of America’s Civil War. To subscribe, click here.