Author: Neither side innocent in conflict

between whites and Native Americans

PETER COZZENS is the author of The Earth Is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West, Alfred A. Knopf, October 2016, $35. He has written or edited 16 books on the Civil War and the Indian Wars of the American West. His next book will be a biography of Shawnee Chief Tecumseh.

What does it mean to balance the historical accounts of whites’ conflicts with American Indians? It means presenting both perspectives as faithfully and evenhandedly as sources permit and examining the actions of both American Indians and  white Americans within the context of those cultures. It’s less a question of restoring balance than of creating balance. No epoch in American history has been more subject to narrative imbalance and mythologizing than the Indian Wars of the American West. The popular concept tends to be an absolute struggle between good and evil, in which the roles of hero and villain reverse as needed to accommodate a changing national conscience. The story was far more nuanced.

white Americans within the context of those cultures. It’s less a question of restoring balance than of creating balance. No epoch in American history has been more subject to narrative imbalance and mythologizing than the Indian Wars of the American West. The popular concept tends to be an absolute struggle between good and evil, in which the roles of hero and villain reverse as needed to accommodate a changing national conscience. The story was far more nuanced.

Why isn’t what happened to the Indians genocide?What is genocide? The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines genocide as “the deliberate killing of a large group of people, especially those of a particular ethnic group or nation.” The government never intended the physical extermination of the native population of the West. But the government did recognize that cultural genocide would be the outcome of a policy, which, in the parlance of the day, was to “civilize” or “Christianize” American Indians—make them peaceable farmers and citizens. And honestly, as tragic as the story is, it really was inevitable that the Indians would be pushed aside. The United States was growing so fast in the 19th century that native ways of life requiring millions of acres of land to support tribal populations of a few thousand were unsustainable.

Who started the cycle of violence? Clearly the whites; in the West, American Indians fought defensively. The proximate cause of certain conflicts was Indian raids—“depredations” as they were often called—but you have to remember that’s the way Indians fought. For them, the common practice of mutilating the dead, which so outraged whites, had a spiritual basis. Warriors believed that a body that entered the afterlife mutilated would pose no threat in that world.

Talk about personalities, starting with the Plains Indian warrior. He would have been raised from boyhood in a culture that extolled warrior virtues. Unless he showed the necessary spiritual gifts to become a medicine man, really the only way to wealth, prestige—and women—was to prove himself as a warrior. So young men strove to distinguish themselves as early as they could on raids against other tribes. Among the Crow, a young man could not even court a girl until he had proven himself in battle by stealing horses or taking a scalp. The greatest feat of courage was counting coup, or touching a live enemy, usually with a decorated lance called a coup stick. Getting close enough to touch an armed enemy without trying to kill him ranked higher than counting a dead enemy. Plains Indians, by the way, considered white scalps far less desirable than tribal enemy scalps. Warriors saw whites—civilians and soldiers—as far less able opponents.

What about the U.S. Army cavalryman? Soldiers in the frontier army were generally from the lowest rungs of society, or were recent immigrants. Many saw the Army as a free ticket to the West. Soldiers deserted in droves after reaching their stations. The exception were the Buffalo Soldiers—black troops who enlisted in large measure to prove the worth of their people. Black cavalrymen were much more reliable, much more dedicated, much less likely to desert than white counterparts. And Buffalo Soldiers were more skilled because they served longer.

Indian agents. During the Indian Wars there were three classes of Indian agent: Many agents were political appointees, who took the job to amass small fortunes by cheating Indians out of their annuities. Army officers, from time to time, were appointed Indian agents. I’ve found no instance of dishonesty among them, and they generally had the Indians’ welfare at heart—after all, if they engaged in any corrupt act, they would be court-martialed and cashiered. The third type were agents chosen by religious denominations, particularly Quakers. They could be too idealistic but they were uniformly honest.

General William T. Sherman. Sherman was doing as ordered, clearing areas of the West for white settlement. When he was angry, he had a tendency to utter some very infelicitous comments. Once, after soldiers were killed, he said, “We must exterminate the Sioux down to the last man, woman, and child.” He didn’t mean that literally. In another breath, addressing a West Point graduating class in the late 1860s while, he advised young officers to help achieve the “inevitable result”—herding the Indians onto reservations—as humanely as possible. So Sherman was of two minds. He was not an exterminationist.

Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull was determined to resist white encroachment—but not by aggressive, offensive warfare. He and his followers wanted to be left alone, and fought only when they had to. So if you define greatness as the determination to defend the traditional way of life, then you could argue that Sitting Bull was the greatest of the Plains chiefs. But is that realistic? I would argue that Spotted Tail of the Brulé was as great a chief as Sitting Bull. Many Lakota viewed Spotted Tail as a sellout because he was the first of the leading Lakota chiefs to come to an accommodation with the whites and settle peaceably on the reservation. But Spotted Tail fought hard and continually for the best possible terms and preserve what he could of his people’s way of life. It depends on how you define greatness.

What do we get wrong about the Little Bighorn? The assumption that General George Armstrong Custer was a fool and that he disobeyed orders. I subscribed to that theory until I began researching the Little Bighorn and realized that in attacking the Lakota-Cheyenne village Custer was carrying out orders from General Alfred Terry. And yes, Custer was outnumbered but he was acting on the best intelligence that the Army had at the moment that he began his mission. The Army assumed that there were at most 800 warriors in the village when in fact, in the days before Custer began his four-day march to the Little Bighorn, that number grew to 1,800. Custer had no way of knowing that—and there was also a longstanding assumption among soldiers that when attacked, the inhabitants of an Indian village would flee. On the afternoon of June 25, 1876, Custer didn’t want to attack; his men were exhausted and he wanted to rest overnight and attack in the morning. But he was led to believe, incorrectly, that he had been discovered. He erred in splitting his command. But to say that he disobeyed orders is incorrect, and to call him a fool for launching an attack is unfair. I think if he had kept his men together he would have prevailed.

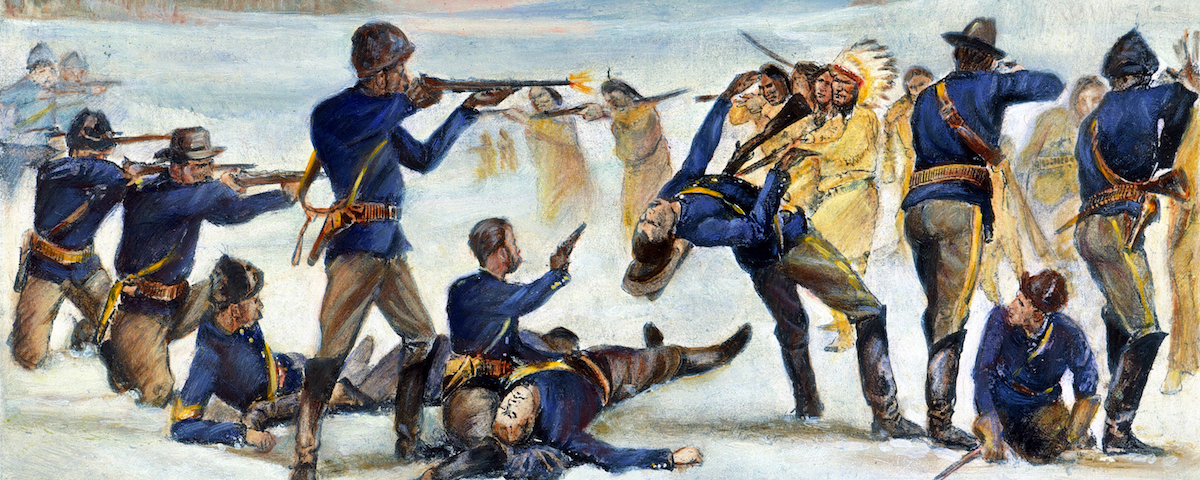

If you could have been present at one moment, what would it be? The tragedy at Wounded Knee, just to make sure that what I conclude is in fact what happened. I do not call Wounded Knee a massacre, because a massacre is the purposeful killing of noncombatants with little or no threat to the perpetrators.

Even in the ravine? In the ravine, individual soldiers committed atrocities. Firing Hotchkiss guns into the ravine was horrible, but among those women and children, there were warriors still firing on the soldiers. It was not the intent of the Seventh Cavalry leadership to massacre noncombatants. Tragically, many women and children who were killed early on were hit by Indian bullets in the crossfire.

Which site did you find the most moving? The site of the Dull Knife fight in November 1876. This was the principal village of the Northern Cheyenne. They were camped in a huge box canyon along a fork of the Powder River in Wyoming Territory. The 4th Cavalry attacked at daylight and the entire village was destroyed—and with it, almost all of the Northern Cheyennes’ cultural patrimony. After the battle, the villagers were forced to flee into the mountains in temperatures that dropped that night to 30 or 40 degrees below zero. That battlefield is preserved with complete integrity because it is on a private ranch. The fact that the site is so well preserved and was the scene of a cultural apocalypse make it particularly haunting and poignant.