The battle of Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana, on June 7, 1863, had little strategic importance, and the total forces involved was small, 1,500 or less on each side. It has been largely forgotten, one of the war’s countless skirmishes. But the percentage of casualties on both sides was among the war’s highest; it was an early test of the Union Army’s new regiments comprised of men of “African Descent”; and the aftermath led to a Congressional investigation and contributed to the decision to end prisoner exchanges.

Author and archivist Linda Barnickel recently brought new attention to the battle with her book, Milliken’s Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory (Louisiana State University Press, 2013). The book was reviewed in the December 2013 issue of Civil War Times. Recently, Barnickel answered some questions for HistoryNet about her book and the battle.

HistoryNet: The battle of Milliken’s Bend isn’t on the radar of most Civil War buffs. How did you come to get interested in it?

Linda Barnickel: It started with a single sentence. I was looking at a post–Civil War broadside for the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery, and it said, Corodon Heath had been “Taken prisoner and murdered by the rebels, July 1862.” Murdered? Why “murdered”? That’s an odd word to encounter when you’re talking about wartime. I wanted to learn more. One of the first things I learned was that the sentence I had read contained several errors.

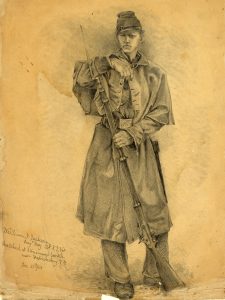

The man’s name was Corydon Heath, not “Corodon,” and the events transpired in June 1863, not in July 1862. He had been a sergeant in Battery G of the 2nd Illinois, but became a captain commanding Company B, 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiment (African Descent) in April 1863. He was taken prisoner during the battle of Milliken’s Bend.

HN: A number of what were called “colored regiments,” comprised of men of African descent, but led by white officers, were formed in areas of the South occupied by Union troops, after Congress authorized the use of “Negro” soldiers. Weren’t some of the men in the Louisiana regiments forcibly recruited?

LB: I think that was quite common. There was a lot of competition for men to fill these new regiments—not only from other regiments, but because “plantation leasees,” Northerners who came South to manage plantations, needed black laborers. Grant was also using them as laborers in his Vicksburg campaign. One officer said something like, “Every man I try to recruit gets snapped up the Quartermaster Department.”

HN: So none of men in these African Descent regiments had been in the army long?

LB: No, a month or two at most. During the battle, an officer was trying to get men to load and fire their rifles, and he asked them, “Don’t you know where your caps are?” (Percussion caps, to be placed on the nipple of a musket to allow it to fire.—Editor) When he looked in the cap boxes, they were full. The men were so new, they didn’t even know what part of their gear held their caps.

Remember, most of the officers were newly appointed, too, like Corydon Heath. They were trying to learn their jobs, so there was a lot of confusion during the battle.

HN: Let’s talk about that battle. What was the significance of Milliken’s Bend? Why did the Confederates attack there?

LB: Grant had his headquarters at Milliken’s Bend in March 1863, but by June it was just one of several supply points along the Mississippi River and was a recruiting point for enlisting former slaves into the Union army. It was a small town about 15 miles above Vicksburg, Mississippi, on the Louisiana side of the river. I have a map showing its location on my Milliken’s Bend website. The town doesn’t exist today; a flood washed it away.

The attack was made by part of (Major General) John G. Walker’s Texas Division. General Richard Taylor wanted to use that division to attack toward New Orleans but was overruled. In the book he wrote after the war he said he was told public opinion would condemn them if they didn’t try to do something to aid Vicksburg. (“I was informed that all the Confederate authorities in the east were urgent for some effort on our part in behalf of Vicksburg, and that public opinion would condemn us if we did not try to do something.”—Ed.)

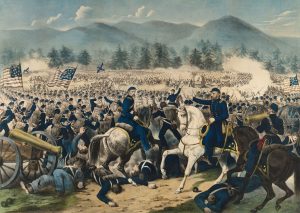

Walker was ordered to simultaneously attack Milliken’s Bend and Young’s Point nearby. (Brigadier General) Henry McCulloch’s Brigade was sent to Milliken’s Bend, which was defended by a brigade of four African Descent infantry regiments—9th, 11th and 13th Louisiana and 1st Mississippi—reinforced with about 120 men from the all-white 23rd Iowa Infantry. The African Brigade was commanded by Colonel Hermann Lieb.

HN: Lieb was originally from Switzerland. Do you think that made commanding black troops more acceptable to him than it was for many Northern officers?

LB: That’s possible; I’ve never seen anything that directly addresses it. But like most European officers of the time he was a stickler for discipline. He was commanding the African Brigade because its commander Isaac Shepherd—who was an abolitionist—was removed for having a white cavalryman whipped by black soldiers of the 1st Mississippi. A court of inquiry later exonerated him.

So Lieb was in charge when McCulloch’s men attacked. Some of the defenders only got off one shot, but a lot of the fighting was hand-to-hand. Even the Confederates praised the courage of the African Brigade.

So Lieb was in charge when McCulloch’s men attacked. Some of the defenders only got off one shot, but a lot of the fighting was hand-to-hand. Even the Confederates praised the courage of the African Brigade.

The casualties were minor compared with those of larger battles, but when you consider the size of the forces involved—about 1,500 or less on each side—the percentage is extraordinary. Estimates of Union losses vary wildly, but most likely they suffered about 100 killed, another 250 wounded, and around 500 missing or captured. The 9th Louisiana lost 68%, the highest total of any of the “colored” regiments during the Civil War; 23% of the regiment was killed—66 men, the highest number killed in action in a single day of any regiment during the entire Vicksburg campaign.

McCulloch lost nearly 200 killed, wounded and missing. On both sides some companies reported losses of 50%. (Confederate casualties totaled about 12%.—Ed.)

HN: There were reports of black troops and white officers being executed after the battle. What did you learn about that?

LB: A man who was a prisoner of the Confederates in Monroe, Louisiana, said two officers captured at Milliken’s Bend were jailed in Monroe, but one night they were taken from the jail and across the Ouachita River where they were killed and buried in a shallow grave.

Most of the black soldiers were put back into slavery. A few may have been executed, but curiously, others seem to have been treated as prisoners of war. They returned to their regiments after the war.

HN: Why do you think some were treated as POWs? That wasn’t common.

LB: I think there was a lot of confusion about what to do; this was an unprecedented situation. The state legislature passed a law two weeks after the battle at Milliken’s Bend calling for the death penalty for any slave enlisting in the Union army. The Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia, had already passed a law permitting the execution of white officers who led black troops, for inciting slave rebellions.

HN: Slave insurrections were always the monster lurking under the bed in the South, Did the battle at Milliken’s Bend increase those fears in Louisiana?

LB: It depends on what source you look at. What I found was a generalized fear, not anything specific to the battle. What really made everybody crazy regarding the possibility of slave rebellion was the Emancipation Proclamation.

HN: Thanks for shedding new light on this little-known battle and for talking with us about it. Did you ever find solid proof of what happened to Corydon Heath?

LB: I’m an archivist, so I’ve followed the paper trail, and I feel confident in the source that said he had been executed. But there are still a lot of questions about Milliken’s Bend that remain unanswered. I’m not done yet!