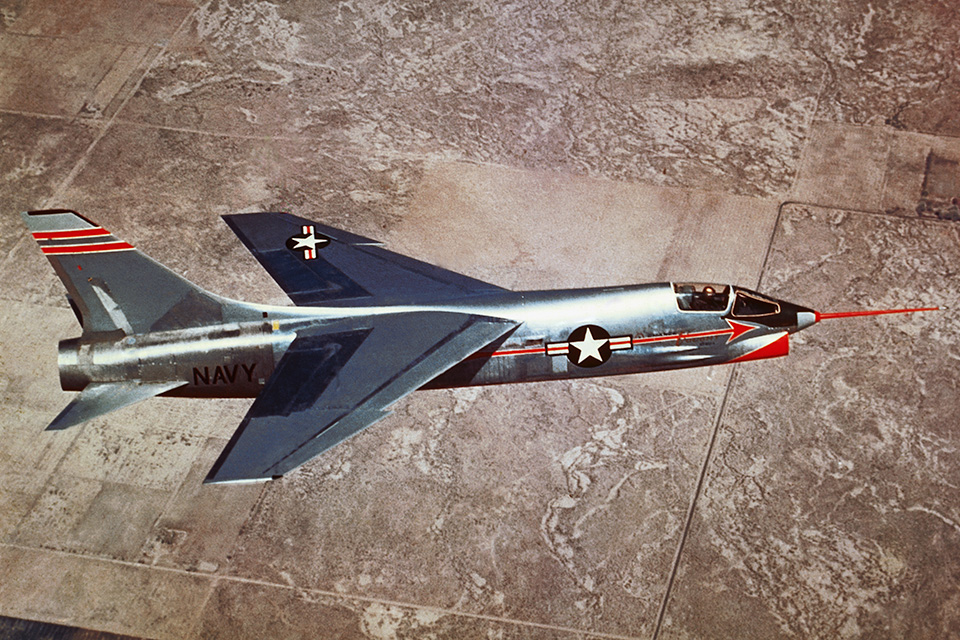

Vought’s F-8 Crusader successfully bridged the gap between the days of close-quarters dogfighting and the supersonic era of long-range missile engagements.

The carrier plowed through the gale-wracked Barents Sea, its escorts shedding white foam as they emerged from mountainous waves, the weather so bad that flight operations were canceled. On the misty horizon, a Soviet trawler tracking the task force was barely visible through the snow squalls.

Aboard USS Independence, one lonely F-8C Crusader of Navy fighter squadron VF-62 sat on the forward catapult. In its unheated cockpit, Lt. j.g. Ron Knott tried to minimize sweating in his “poopy suit,” his only protection against nearly instantaneous death in subfreezing waters should he be forced to eject. For two hours of his four-hour watch Knott had watched green seas cascade over the bow of the 60,000-ton carrier. “That means water, not spray, somehow elevated itself 80 feet to come over the flight deck, or the flight deck was diving 80 feet into the North Atlantic, which was in fact what was happening,” he recalled. “I was pulling 4 positive and 4 negative Gs just sitting in the cockpit.” His poopy suit was beginning to chafe in uncomfortable places. Independence was 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle, within attack range of Murmansk. It was 1964, a time when the Cold War could quickly get hot.

“We were there to antagonize the Russian bomber fleet,” Knott continued. “Anytime they crossed an imaginary line 250 miles out, we would intercept them. We knew when they got airborne in Russia, but we didn’t want them to know we knew, and we didn’t want them to know we had the capability of intercepting them beyond 250 miles should a real threat arrive. So two fighters would join them as soon as they stuck their nose across the 250-mile circle and escort them around the fleet.”

While a standard combat air patrol was maintained over the fleet during normal flight operations, after ops were secured two fighters were on the catapults ready to go if a target approached the magic 250-mile circle.

“Weather conditions were too rough for normal flying due to the rough sea, and flight operations were canceled, but not the duty fighter,” said Knotts. “Of course, I knew there was no way they would launch me in such conditions, even though it was daytime and mostly clear. Normally the mission involved two airplanes, but it was just me that day, due to the other cats being blocked by aircraft they couldn’t move on account of the thin sheet of ice that covered the flight deck, which made taxiing impossible. It had taken 10 sailors on each side of my aircraft just to push me onto the cat. Each time the ship rolled starboard, the airplane would slide right, and when she rolled port, it would slide left. They had my airplane tied down on the cat with at least 10 heavy chains, and I still felt helpless.”

With a closed canopy and the ventilation off, the cockpit air got so musty Knott had to crack the canopy every few minutes for fresh air. The worst part was to be launched after about 3½ hours, in need of answering nature’s call.“They used to tell us,‘Son you can’t buy experience like this in the civilian world,’” he said.“And we would respond,‘And you can’t give it away either!’”

Suddenly the bullhorn from Primary Flight Control cut through the blasting wind over the frozen flight deck with an unbelievable order: “Launch the duty fighter!”

Without radio contact, Knott was at first unsure what he’d heard, but when the command was repeated, “I thought to myself, ‘You have got to be kidding!’ I saw the launch crew start taking off my 10 tie downs, and getting a ground starter in place. They gave me the two-finger turn up and pointed to my headset. I knew that this was a signal to call Pri-Fly. Before I could, they were briefing me: ‘We have an unidentified target approaching the 250-mile circle. You will be launched as soon as the ship can turn into the wind.’ My reaction was ‘Oh, shit!’”

The launch crew readied the Crusader while Knott prepared himself: “After checking all engine instruments in desperate hope of finding a major problem, I determined all systems were go. It was bred into us naval aviators to never turn down a mission just because it was not the best one of the day. And there were 3,500 of my fellow sailors aboard, watching to see if this fighter pilot really was a Fighter Pilot.”

The waves were so high the catapult officer had to time the movement of the bow to be certain they launched on the upswing, to give Knott a fighting chance of getting airborne. “The nose of the ship would be buried in a 30-degree dive into the waves, and the next moment it would be climbing the front of a wave with a 20-degree bow-up attitude. And all the while this 60,000-ton ship was rolling port to starboard 15 to 20 degrees like she was a destroyer.”

Knott saluted the Shooter, and sat back for the 26-G cat shot. At that moment, he was at 100-percent power, with the afterburner blazing a stream of hot air down the flight deck. With the Crusader straining its brakes, the launch was delayed because of sea conditions. Knott continued to hope Pri-Fly would cancel the flight. “No such luck,” he said. “When the bow of the ship started up I was airborne in a flash. In the Crusader, we would get a shot that would produce about 180 knots in 1.8 seconds. There was no way you could keep your feet on the rudder pedals. Going off, we felt like the Roadrunner and would sometimes key the mike and say, ‘Meep-meep.’”

As Knott retracted his gear, Combat Control radioed vectors. “The F-8 would accelerate to supersonic speeds in just a few moments, even while climbing at 25,000 feet per minute. In less than 90 seconds I was at 30,000 feet, supersonic.” Control was turned over to the radar picket destroyer, which soon informed Knott that it appeared this was a false target, a condition sometimes caused by rough seas. “Wow! Here I had risked my life for a false target, and the worst part was not yet over,” he said.“I still had to land on a boat that was bouncing like a cork.”

It took 10 minutes to get back. “I knew my task had just begun. Being shot off the ship was dangerous, but the pilot had very little control of that event. Now I had to land on that same ship that was being beat around like a puppet by Mother Nature. This is no easy task under normal conditions, but adding a pitching deck going through an 80- foot arc made it even more tense.”

Knott was given “Charlie on arrival,” meaning he could land as soon as he reached the ship. “Normally, fighters came back with only enough fuel for about three landing attempts, four at most. If a plane needs more fuel, due to a crash on deck, or a bad landing day, tankers are available to give them another drink for more flying time. There were no tankers that day, and I had enough fuel for about six landing attempts. Thank goodness I did.”

The pilot usually flies his approach looking at the “meatball,” a bright light on a predetermined glide slope that, if followed precisely to touchdown, places the aircraft in the middle of the arresting cables. The light is gyro-stabilized for steadiness in case the ship is rocking and rolling.“I entered base to final and caught the ball,” Knott remembered. “With the ship heaving and bucking, the landing signal officer [LSO] was controlling the meatball manually to keep me on the glide slope. I took a deep breath and concentrated: hands on throttle and stick, head up, fly the ball.”

In a normal landing, the pilot can’t see the movement of the ship during approach. “On this day, I could see the movement loud and clear. At one moment the ship would be in a 20-degree left roll with the bow high, which is impossible for a landing, like flying into a wall. Next glance it would be bow low, rolling both left and right. I could look out and see the bow of the ship go underwater, while the stern came out of the water so high the screws were exposed. The whole ship shuddered as the bow rose and the screws bit into the water again. I knew I was in deep, serious trouble.”

The LSO tried to judge the frequency of the waves, to bring the Crusader aboard when the ship was somewhat level.“The LSO let me fly in as close as possible before he hit the red flashing lights that meant ‘wave off.’ After five aborted attempts, my poopy suit was filled with sweat. I only had fuel enough for one final attempt. If I did not land on this pass the engine would flame out and I would have to eject into water, where I would have frozen to death in minutes even with the suit on, because of the sweat. Needless to say I was calling on a higher power to help me get this beast on board that big boat. It was the best landing pass I ever made, and I was allowed to continue to a landing. I can honestly say when I felt that tail hook engage, I was the happiest man on that ship.”

Knott’s problems weren’t over yet.“I had to taxi out of the landing area. There was still that thin sheet of ice all over the deck. Each time the ship would roll, the aircraft would skid in that direction. I had observed an airplane skid overboard after making a beautiful landing just a few days before. I knew this could happen to me. Not many pilots survive falling overboard while strapped in. The 80- foot fall usually knocks them out, or their injuries keep them from escaping and they sink with the airplane.”

Everyone on the flight deck and the island watched as Knott applied power at the moment the deck was relatively level, and taxied out of the arresting gear. The deck crew then surged forward and finally got enough chains and tie downs on the Crusader to keep it from taking a saltwater swim along with the pilot.

“The captain congratulated my airmanship,” he recalled.“The flight surgeon gave me a few ounces of brandy.”When Knott slid into his bunk, he had to use the wide leather strap to secure himself. “The ship was still bucking like a bronco, and it felt like I was pulling plus and minus 3 Gs lying in my bunk.”

Like most every other pilot who ever strapped on a Crusader, Ron Knott says it was the best airplane he ever flew. One of the original pilots of VF-62 following its conversion to the Crusader, Knott first flew combat missions as escort for the RF-8 Crusaders during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October and November 1962. The photo-Crusaders were the only reconnaissance aircraft in the Navy at the time capable of surviving low-level missions in the high-threat environment over Cuba. “We’d take the recon birds in at about 100 feet altitude, in max afterburner,” Knott remembered. “The ground was just a streak below us, we were going so fast, and we were in and out of the country in under 10 minutes, which gave them virtually no time to shoot at us.” The low-level photographs these missions returned with provided the evidence that the Soviets were living up to their agreement to remove missiles from the country. The RF-8s would go on to provide the backbone of tactical photoreconnaissance for the fleet throughout the coming conflict in Vietnam.

Aviation historian William Green once described “greatness” in a combat aircraft this way: “Greatness is a quality that cannot be instilled in an aircraft on the drawing board or the assembly line. A great aircraft must have that touch of genius which transcends the good, and it must have luck—the luck to be in the right place at the right time. It must have flying qualities above the average; reliability, ruggedness and fighting ability; and, in the final analysis, it needs the skilled touch of crews to whom it has endeared itself.” The F-8 Crusader was not only lucky, but good to boot, more than fulfilling each of Green’s decisive qualities. As the last all-gun U.S. Navy fighter to achieve production, the Crusader ranks as one of the true greats in aviation history—not only as a combat airplane, but also as a technological achievement.

Chance Vought had been on the cutting edge of naval aircraft development ever since the VE-7, the Navy’s first carrier-based airplane. Vought’s legendary F4U Corsair was one of the best naval fighters of World War II. Though the Corsair was still in production in 1952, the end was in sight. Yet Vought hadn’t created a successful follow-on design: The F6U Pirate was underpowered, and the F7U Cutlass was both underpowered and difficult to operate from a carrier. Vought needed a major success if it was to remain a player.

The Crusader’s luck began when the design was freed of the dreadful Westinghouse J40 turbojet and allowed to use Pratt & Whitney’s great J57. Boasting a new afterburner, the J57 was set to power the Air Force’s first supersonic fighter, the North American F-100 Super Sabre.

Luck continued through the airframe’s design. Vought’s team was working prior to the publication of Richard Whitcomb’s famous area rule, but they managed to get the design so right that the F-8 flew fully supersonic without the need for the “coke-bottle” fuselage or “wasp waist” forced on other designs once the rules for supersonic flight were known. The entire wing, other than the outer folding section and control surfaces, was a gas tank, with other tanks installed throughout the fuselage. Vought was also lucky to create the first supersonic wing with the all-important “dog-tooth” from the beginning. In the end, the wing-body shape was so right that the Crusader was a generation ahead of its competition.

Mating a high-performance fighter like the Crusader to a carrier deck was the real challenge. Vought’s solution—creating the first variable-incidence wing—was truly elegant. Coupled with full-span leading-edge slats and drooping ailerons, this allowed the fuselage to remain at an angle that gave the pilot sufficient visibility for a carrier landing, while not forcing loads onto the landing gear that would result in the usual weight escalation for naval aircraft in this area. As Ron Knott explained,“I couldn’t have made that landing in another airplane because I couldn’t have seen the deck.”

The prototype first flew on March 25, 1955, powered by the Air Force version of the J57, which provided less thrust than the definitive Navy version. Even so, Vought chief test pilot John Konrad easily took the Crusader out to Mach 1.2 on its first flight. In comparison to the F-100, the Crusader had longer range, faster climb, more rapid rate of roll, a smaller turning radius at all speeds and heights, as well as lower landing speed and a shorter landing run. So few changes were found necessary that the third Crusader delivered was the first full-production aircraft. The only visible alteration was the addition of a flight refueling probe on the left side of the forward fuselage, resulting in a bulge that actually added to aerodynamic smoothness. The other major change was adding the capability to use the Sidewinder missile.

In April 1956, the Crusader made its first carrier landing aboard USS Forrestal, and six months later demonstrated the ability to operate from a modernized WWII-era Oriskany-class carrier. On August 31, 1956, Commander R.W. “Duke” Windsor took one of the first production F8U-1s up to 36,000 feet over China Lake, Calif. He pushed the throttle forward as he entered a 15-kilometer course and set a national speed record of 1,015 mph, an achievement for which he was awarded the 1956 Thompson Trophy.

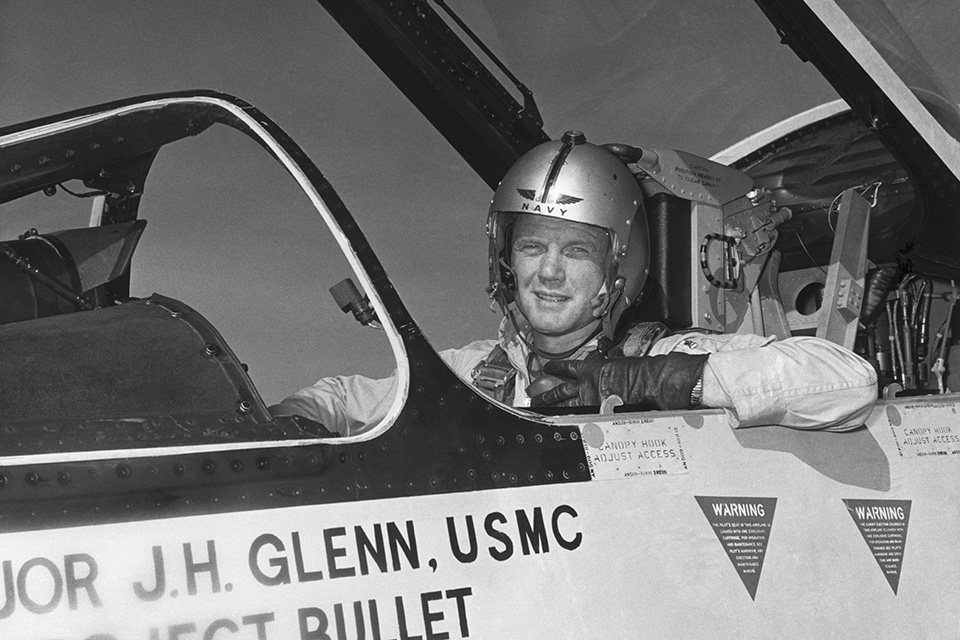

The public first caught wind of the Crusader on July 16, 1957, when an F8U-1P flew from Los Angeles to New York in three hours, 23 minutes, 8.4 seconds, for an average speed of 726 mph, or Mach 1.1. The Crusader had to come down from 35,000 feet to 25,000 feet and slow to 320 mph to refuel three times from North American AJ-2 Savage tankers, and was actually flying in full afterburner at Mach 1.7 for the majority of the mission. The Marine aviator who earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for that feat, Lt. Col. John H. Glenn Jr., would become far better known in February 1962 as the first American to orbit the earth. Vought topped off a winning year in December 1957 when it won the Collier Trophy for having designed the Crusader.

Vought’s production lines turned out a succession of models: 130 F8U-1Es, which had full all-weather capability with addition of the APS-67 radar, followed 318 F8U-1s and 144 F8U-1Ps. The 187 F8U-2s received the more powerful J57-P-16 engine, which required adding two ram air intakes in the extreme rear fuselage to cool the hot afterburner, and ventral fins for supersonic stability. The fastest were the 152 F8U-2Ns, which appeared in 1960 with new APQ-83 radar and the J57-P-20 engine, boasting a level speed of 1,230 mph. The 296 F8U-2NEs had the new APQ-94 radar that required a slightly larger nose and an IR-seeker. Introduced as the F-8E following the 1962 change in aircraft designations, it was heavier and had a slower top speed of 1,133 mph, but it also had ground-attack capability built in, the first Crusader to serve as a “mud-mover.” The last new-build Crusaders were 42 F-8E(FN)s produced for the French navy.

In 1965 the Crusader went to war in Vietnam. On October 9, 1966, the F-8E finally met the fighter it had been designed to defeat.

On that day four F-8Es were “feet dry” at 20,000 feet over the Red River. Below, the Douglas A-4 Skyhawks they were tasked with escorting dodged the opening bursts of North Vietnamese flak. Air Combat Control warned of enemy aircraft in the area. Moments later, the threat became real as four silver delta-winged shapes flashed past. Commander Richard M. “Dick” Bellinger, executive officer of VF-162 (“The Hunters”), recognized the MiG-21s as he accelerated after number four. He felt a wave of adrenaline as he passed easily through Mach 1 and closed with the target.

The pilot of the trailing MiG saw his nemesis approaching and tried to maneuver away. Bellinger settled into position at 6 o’clock and fired two of his four Sidewinder missiles. Hit in the rear fuselage, the MiG erupted in a fireball. The Crusader had just become the victor in history’s first all-supersonic combat.

Bellinger’s victory was the first of three over the MiG-21 scored by Crusaders, along with 16 MiG-17s, which earned it the nickname “MiG Master.” Despite being originally designed as “gunfighters,” Crusaders shot down just four MiGs with guns only, since the cannon armament proved troublesome, with guns jamming during rapid turns and high accelerations due to the ammunition belts developing kinks.

During the war, 42 Navy F-8s and 20 RF-8s, as well as 12 Marine RF-8s, were lost to flak and small-arms fire. Ten Navy Crusaders were shot down by SAMs, while 20 RF-8s from VFP-63 and 12 from VMCJ-1 were downed by SAMs or flak. At least three F-8Es were lost to MiGs.

The Crusader remained in first-line U.S. Navy service until 1976, when the last of the Oriskany-class carriers was decommissioned. But that didn’t mark the end of the F-8’s combat career.

In 1962 the French navy was being modernized, with two new aircraft carriers, Foch and Clemenceau, replacing its WWII-vintage light carriers. Slightly smaller than the Essex class, the new flattops were designed from the outset with angled decks.

The Aquilon, a French-built de Havilland Sea Venom, was ready for replacement in the all-weather interceptor/fleet defense role. The best French-designed carrier jet, the Dassault Etendard, was not capable of development into a world-class air superiority fighter. The French navy was thus forced to look at foreign aircraft. Both the Crusader and the F-4 Phantom II were considered, but in the end the Crusader got the nod.

In order for the Crusader to be able to operate from the smaller French carriers, however, its landing speed had to be reduced by 10 knots. The F-8E, considered the definitive production version and capable of employment as a multi-role air defense or tactical strike fighter, was what the French wanted—if it could be tamed.

The solution involved increasing the wing’s angle of incidence from 5 to 7 degrees, with the leading-edge slats split to provide increased camber at landing speed, coupled with a boundary control system blowing air from the engine over the flaps and ailerons. With this, landing speed dropped an impressive 12 knots. Larger elevators allowed authoritative control response at this low landing speed. With these changes, the French ordered 40 single-seat versions of what was called the F-8E(FN). The idea was so good, the U.S. Navy had its F-8Es remanufactured to the same standards beginning in 1968, as the F-8J.

The first F-8E(FN) Crusaders arrived at Saint Nazaire on October 5, 1964, where Flotille 12F became the first unit to equip with “Le Crouze,” as the airplane became known in the French navy. Although it never saw combat, Le Crouze did serve in war zones. F-8E(FN)s participated in the Beirut crisis of the early 1980s. In 1988 Clemenceau joined the international response to attacks by Iranian speedboats on shipping in the Persian Gulf, with Iranian aircraft intercepted on several occasions.

By the late 1980s, Le Crouze was long in the tooth, but its projected replacement, the Rafale-M, was delayed in development. The Crusader’s life had to be extended in order for the French navy to keep a fleet defense component. The result again demonstrated the remarkable adaptability of the basic airframe. Upgrades included a new zero-zero MartinBaker Mk. 7 ejection seat and new avionics to improve all-weather flight capability. The Mirage F1’s gyroscopic navigation system was adopted, and a radar-warning receiver was mounted in a vertical fin extension. By September 1994, a dozen aircraft had been modified and given the designation F-8P.

The 12 F-8Ps saw considerable service in their final years. In 1995 they operated over the Balkans during the NATO intervention in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Crusader’s final military mission came in June 1999 over Kosovo. By then the F-8Ps were so fragile that they required 67 maintenance man-hours for each flying hour. The last operational Crusaders were retired on December 15, 1999, more than 42 years after the F8U debuted with the U.S. Navy. No other modern jet fighter had served longer in first-line service.

Aviation writer and photographer Thomas McKelvey Cleaver has flown in everything from a restored World War I Jenny to an F-4E Phantom. Further reading: Crusader! Last of the Gunfighters, by Paul T. Gillcrist; MiG Master: The Story of the F-8 Crusader, by Barrett Tillman; Vought F-8 Crusader, by Peter Mersky; and Supersonic Fighter Pilots (aka Supersonic Cowboys), by Ron Knott.

Originally published in the January 2012 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.