Militants hoped the bombing of Iraq’s al-Askari shrine would inflame a sectarian civil war between the nation’s Sunni and Shiite Muslims—and they got their wish.

Though bloodless, the Feb. 22, 2006, bombing of the al-Askari shrine in Samarra, Iraq, sparked sectarian warfare nationwide, particularly 60 miles south in Baghdad, where residents streamed from their neighborhoods seeking either reprisals or refuge. The violence quickly spread, claiming hundreds of civilian casualties in the first week alone. As intended, the explosion had shattered the relative peace between Iraq’s contentious Sunni and Shiite sects, sparking a civil war that has yet to end.

The al-Askari shrine—commonly called the Golden Mosque, in reference to the gold sheathing installed on its dome more than a century ago—is one of the oldest and most revered sites in Shiite Islam. Built during the 9th century, it contains the entombed remains of two of the sect’s most important figures—imams Ali al-Hadi and his son Hasan al-Askari, the namesake of the shrine. Al-Hadi and al-Askari were the 10th and 11th of the Twelve Imams, the spiritual and political successors of Muhammad, the 7th century founder of Islam.

Though members of both al-Qaida and various Shiite militia groups were known to have infiltrated Iraq’s security forces, the lapses that had allowed the bombing of the mosque were clear indications of just how compromised the fragmented nation’s military and law enforcement agencies had become. Moreover, the incident blew up into a crisis for U.S-led coalition forces in Iraq. Though no one was killed, the partial destruction of the famed golden dome outraged Shiites, and militia forces ranging from the Mahdi army to Hezbollah considered the act tantamount to a declaration of holy war.

On the heels of the U.S.-led invasion three years earlier Muqtada al-Sadr had founded the Mahdi army, which grew into a network of Shiite militias with significant representation in the Iraqi parliament. The militia leader’s father and father-in-law, both Shiite clerics, had been killed on the orders of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. Regardless, he called the bombing “a plan by the occupation to spark a sectarian war” and specifically blamed the United States and Israel. While patently untrue—the attack conflicting with the regional interests of both nations—al-Sadr’s words further inflamed Iraqi Shiites, who already saw themselves as second-class citizens. Before the invasion Saddam’s minority Sunnis had dominated Iraq. Indeed, one of the few points of favor coalition troops found among the majority Shiite population was that they had toppled the dictatorship and liberated the long-oppressed sect. After the bombing, al-Sadr played a key role in changing that positive perception, and the Mahdi army became an even more intractable enemy to the U.S.-led occupation.

President George W. Bush immediately spoke out against the bombing. “The United States condemns this cowardly act in the strongest possible terms,” he wrote in a statement from the White House. “I ask all Iraqis to exercise restraint in the wake of this tragedy and to pursue justice in accordance with the laws and constitution of Iraq.” Coalition forces had been seeking to curb deaths among the civilian population using counterinsurgency tactics. The bombing hampered such efforts.

In a televised appearance Iraqi Prime Minister Ibrahim al-Jaafari, a Shiite, called for a three-day mourning period. In a counterproductive public statement of his own Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, Iraq’s most senior Shiite cleric, insisted, “If the government’s security forces cannot provide the necessary protection, the believers will do it.”

Ultimately, Sunni insurgents inspired by Jordanian-born al-Qaida adherent Abu Musab al-Zarqawi claimed responsibility for the attack. Knowing they could not defeat the U.S.-backed majority Shiite government on the battlefield, they wanted to incite a civil war between Shiites and Sunnis, a chaotic conflict from which Zarqawi and his followers hoped to emerge triumphant.

The blowback from his ruthless strategy was severe, as within a day of the bombing Shiite militiamen killed or kidnapped two dozen Sunni clerics and targeted dozens of the sect’s mosques across Iraq with drive-by shootings and rocket attacks. The militiamen also roamed Sunni neighborhoods, kidnapping and executing civilians at will. In reprisal attacks al-Qaida targeted Shiite market places, cafés and even funerals with suicide car bombings, killing and injuring scores. According to the Iraqi government 3,438 civilians died violently in July 2006 alone, making the month one of the deadliest for civilians during the Iraq War. Indeed, the bloodshed was so terrible that al-Qaida founder Osama bin Laden himself reportedly told Iraqi supporters the slaughter gave a bad name to the entire organization.

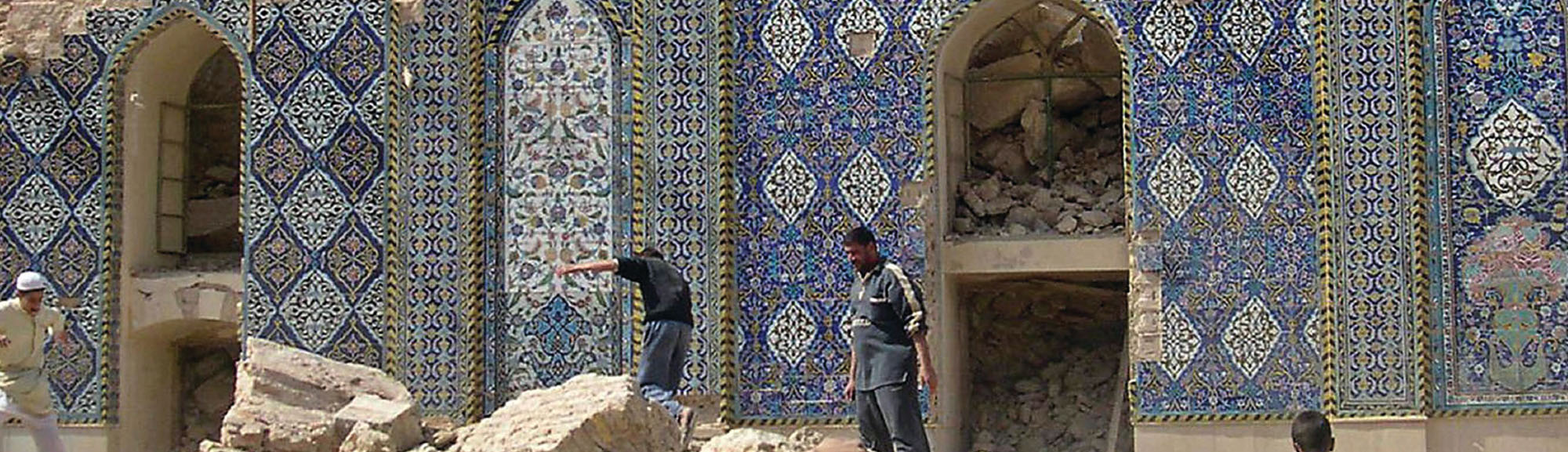

Regardless, Sunni militants must have perceived the carnage and political instability that followed the bombing of the Golden Mosque as productive, as they bombed the edifice a second time. That attack, on June 13, 2007, toppled the twin 10-story minarets that had survived the 2006 assault. It also poured yet more fuel on Iraq’s already blazing Sunni-Shiite civil war.

In a 2007 interview General David Petraeus, architect of the surge strategy employed earlier that year to stabilize the country, responded to the attack in hopeful tones. “This is a serious blow,” he began, “but frankly, it is our hope that this can galvanize the Iraqi leaders to unite against this form of extremism. As you’ll recall, this is a continuation of some attacks that took place a couple of weeks ago as well against some Sunni mosques. And, in fact, so far all Iraqi leaders have united, have joined, have linked arms in condemning this action.”

Petraeus then made an indirect appeal to al-Sadr: “There have been different messages that have come out of Muqtada al-Sadr in the past week or so. Interestingly, some of those have been a bit more pragmatic and accommodating.”

But al-Sadr had no intention of making peace with the United States. Indeed, his rhetoric strategically and routinely blamed U.S. forces for atrocities with which they had nothing to do.

The Mahdi army remained a fearsome organization that targeted coalition forces and the poorly trained and equipped Iraqi government troops, as well as civilians and the infrastructure in Iraq. Its attempts to engage U.S. forces in open combat generally ended in disaster with heavy casualties. But when the Mahdi army switched to guerrilla tactics and gained material support from Iran—which supplied it with improvised explosive devices that could penetrate armored vehicles—its insurgent forces became a real threat to coalition troops.

In the end the Iraq War was less a clash between insurgents and coalition troops—who had initially thought of themselves as liberators—than a sectarian civil war that happened to embroil U.S.-led forces. The al-Askari shrine remains a flash point of the continuing conflict in Iraq and the surrounding region. As recently as 2014 Sunni militants of the Islamic State, or ISIL, launched mortar shells at the site, wounding nine Iraqis. Their motives were the same as those of the attackers before them—to cause so much internecine fighting that the country would collapse and they could rule as kings over the rubble. MH

Stephen Carlson served two tours in Afghanistan as an infantryman with the 10th Mountain Division and is now employed by United Press International.