I have a kimono taken from Japanese submarine I-14 by a fellow submariner friend, Lou Reynolds, after I-14’s surrender in August 1945. I’m assuming the garment belonged to the sub’s commanding officer. The kimono, almost floor length and in perfect condition, has five identical crests, including the two shown on each shoulder. I would like to know the meaning of the crest and would like to return the kimono to the commander’s family if possible. —Dan Moss, Denver, Colorado

I have a kimono taken from Japanese submarine I-14 by a fellow submariner friend, Lou Reynolds, after I-14’s surrender in August 1945. I’m assuming the garment belonged to the sub’s commanding officer. The kimono, almost floor length and in perfect condition, has five identical crests, including the two shown on each shoulder. I would like to know the meaning of the crest and would like to return the kimono to the commander’s family if possible. —Dan Moss, Denver, Colorado

On August 27, 1945, patrolling aircraft from the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 38 sighted a Japanese submarine running on the surface, 200 miles from Yokohoma, Japan. It was I-14, a massive fleet submarine with a built-in hangar capable of carrying two floatplanes. Originally designed to attack the continental United States or the Panama Canal, I-14 was, in its final mission, to launch scout planes for a surprise raid on the U.S. fleet at Ulithi Atoll. Before that mission could take place, its captain, veteran sub commander Shimizu Tsuruzo, received word of the Japanese surrender. Three days later, in accordance with orders and flying a black flag, he departed on the surface for the nearest port in Japanese home waters.

USS Murray was dispatched to rendezvous with I-14 and escort it to Tokyo Bay. The next day, USS Bangust arrived with a prize crew—including Seaman First Class Louis C. Reynolds—to take possession of I-14. Lou removed this garment—possibly a haori, a long jacket worn over a kimono—from an open closet.

Over the next few months the prize crew sailed I-14 to various ports in Japan, always keeping the 3,700-ton Japanese submarine ready to sail back to the United States as a war trophy. Ultimately, the navy sent I-14 to Hawaii along with two other Japanese super submarines, I-400 and I-401, for further inspection. On May 28, 1946—to keep its technology a secret and test a new torpedo exploder—the USS Bugara sank I-14 off of Barber’s Point, Hawaii.

The garment’s crest is a “kamon,” or family crest; that it has five of them identifies it as a piece of formal apparel of high status. Marked with two sparrows over bamboo shoots, the kamon is well-known in Japan. It was used by members and vassals of a famous warrior family, the Uesugi clan. Kenshin Uesugi was a feudal leader in north-central Japan during the country’s Middle Ages. A revered figure, he would have been well known to every Japanese schoolboy growing up in the early twentieth century. The kimono’s owner was not necessarily a blood relative of Uesugi; his link may have come through marriage, work for a clan member, or residence in the clan’s former domain.

Returning the garment to its original owner’s family may be difficult. “Trying to contact veterans or their survivors in Japan is often a hit-or-miss affair,” explains Hiroyuki Shindo, of the National Institute for Defense Studies in Tokyo. “Unless you know somebody who is a personal acquaintance of a veteran or descendant, or somebody who is directly involved with a veterans association, tracking down a veteran or descendant can be extremely difficult.”

Another mystery is the garment’s presence aboard I-14: Imperial Navy regulations forbade taking personal possessions onboard ship. —Josh Schick, Curator ✯

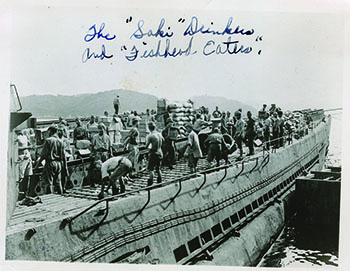

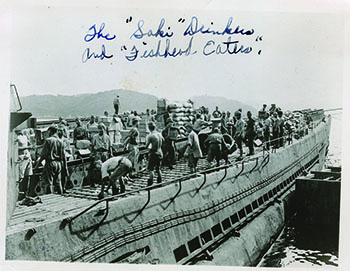

An American flag flies triumphant on I-14’s mast, over the Imperial Navy ensign (top). “I was in the crew that boarded the Japanese submarine,” Lou Reynolds—now 92 and living in Arizona—writes. “Four or five of us were dispatched to go down and

An American flag flies triumphant on I-14’s mast, over the Imperial Navy ensign (top). “I was in the crew that boarded the Japanese submarine,” Lou Reynolds—now 92 and living in Arizona—writes. “Four or five of us were dispatched to go down and  inspect the interior. It was stifling. Barrels

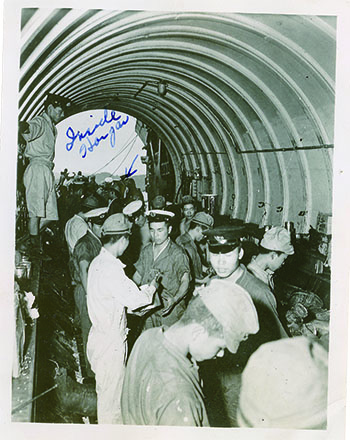

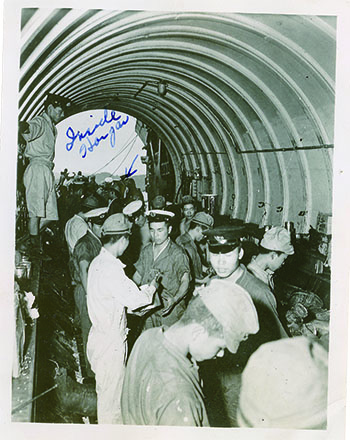

inspect the interior. It was stifling. Barrels  of fish heads and rice along with cases of sake.” For the next four months, Lou lived aboard sub tender USS Proteus at night and I-14 (center) during the day, learning from the Japanese crew how to operate the boat in anticipation of bringing it to Pearl Harbor. Although the sub could carry two attack floatplanes, they were absent at the surrender. About a small figure in the background of a photo of the hangar (bottom), Lou says: “I could swear that is me.”

of fish heads and rice along with cases of sake.” For the next four months, Lou lived aboard sub tender USS Proteus at night and I-14 (center) during the day, learning from the Japanese crew how to operate the boat in anticipation of bringing it to Pearl Harbor. Although the sub could carry two attack floatplanes, they were absent at the surrender. About a small figure in the background of a photo of the hangar (bottom), Lou says: “I could swear that is me.”

An American flag flies triumphant on I-14’s mast, over the Imperial Navy ensign (top). “I was in the crew that boarded the Japanese submarine,” Lou Reynolds—now 92 and living in Arizona—writes. “Four or five of us were dispatched to go down and

An American flag flies triumphant on I-14’s mast, over the Imperial Navy ensign (top). “I was in the crew that boarded the Japanese submarine,” Lou Reynolds—now 92 and living in Arizona—writes. “Four or five of us were dispatched to go down and  inspect the interior. It was stifling. Barrels

inspect the interior. It was stifling. Barrels  of fish heads and rice along with cases of sake.” For the next four months, Lou lived aboard sub tender USS Proteus at night and I-14 (center) during the day, learning from the Japanese crew how to operate the boat in anticipation of bringing it to Pearl Harbor. Although the sub could carry two attack floatplanes, they were absent at the surrender. About a small figure in the background of a photo of the hangar (bottom), Lou says: “I could swear that is me.”

of fish heads and rice along with cases of sake.” For the next four months, Lou lived aboard sub tender USS Proteus at night and I-14 (center) during the day, learning from the Japanese crew how to operate the boat in anticipation of bringing it to Pearl Harbor. Although the sub could carry two attack floatplanes, they were absent at the surrender. About a small figure in the background of a photo of the hangar (bottom), Lou says: “I could swear that is me.”

This column was originally published in the December 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.