Many Vietnam veterans had their lives and careers shaped by military, political and diplomatic actions during the war, but Colin Powell is the only one who helped shape military, political and diplomatic actions at the highest levels after the war.

He served in the office of Defense Secretary Harold Brown during Jimmy Carter’s administration and in the office of Ronald Reagan’s defense secretary, Caspar Weinberger. Reagan made Powell his national security adviser in 1987. Two years later George H.W. Bush appointed him chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, a

position he continued to hold in Bill Clinton’s presidency until October 1993. He culminated his government career as George W. Bush’s secretary of state from January 2001 to January 2005.

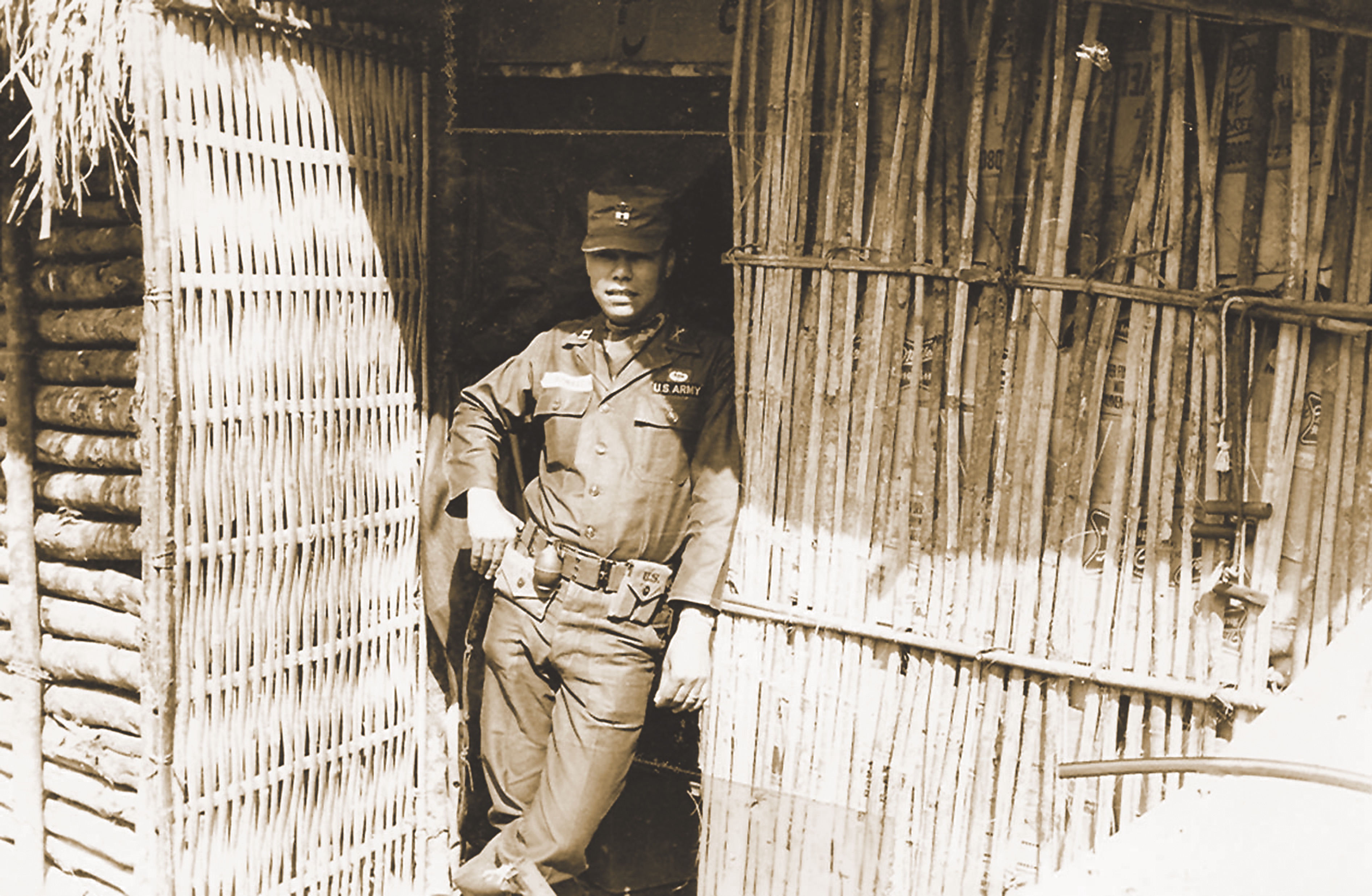

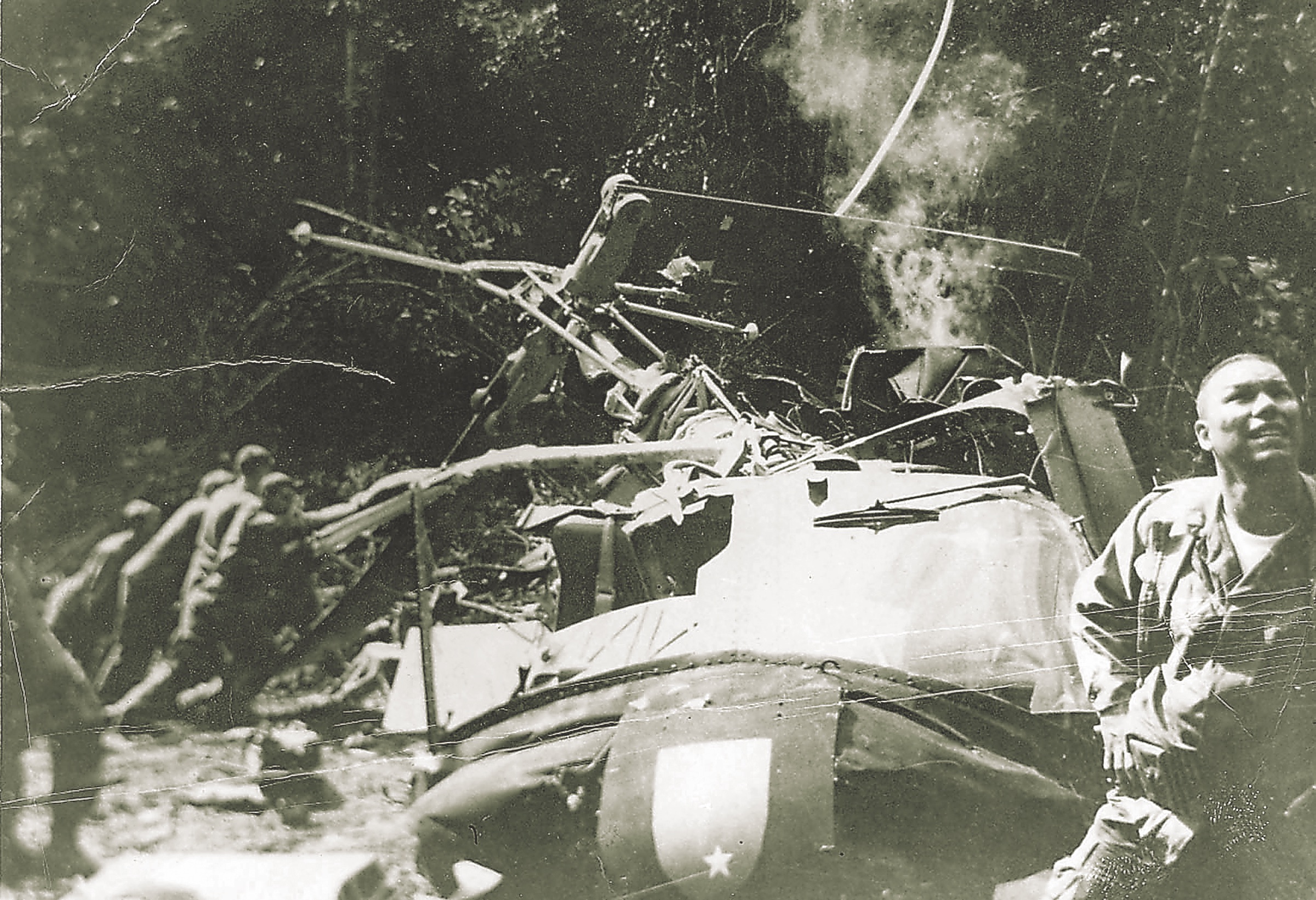

Powell, a City College of New York ROTC graduate commissioned a second lieutenant in June 1958, served in Vietnam as a captain advising South Vietnamese units from December 1962 through November 1963 and as a major in the 23rd Infantry Division (Americal) from June 1968 through July 1969.

After returning to the United States, he earned an MBA from George Washington University in 1971 and was selected for the White House Fellows program, which enabled him to spend a year working in President Richard Nixon’s Office of Management and Budget.

His rise up the ranks included positions as a battalion commander in Korea, a brigade commander in the 101st Airborne Division and commanding general of V Corps in Germany. In April 1989, Powell was promoted to four-star general and that October became Joint Chiefs chairman, not only the first African-American in that position but also the youngest officer (age 52) and first ROTC graduate.

He oversaw the December 1989 intervention in Panama to oust dictator Manuel Noriega, who refused to relinquish power after democratic elections and had been charged with drug trafficking. But Powell’s real rise to fame occurred during the 1991 Gulf War’s Operation Desert Storm, launched after Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi forces invaded neighboring Kuwait.

Powell’s tenure as secretary of state was marked by some of the most tumultuous events in recent American history: the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 and the invasion of Iraq in March 2003.

Powell talked about his experiences in Vietnam, lingering controversies of the war, the lessons he drew from it and why he never ran for president in an interview with Vietnam Editor Chuck Springston.

In your memoir, My American Journey, you recall a conversation with South Vietnamese Captain Vo Cong Hieu at a base in the A Shau Valley during your first assignment in the field. He said something that would come to sum up the war in your mind. I got out of the helicopter, looked around and saw that the base was against the side of a mountain, and the other side of the mountain was Laos. There we were, in a huge triple-canopy forest. And logic says, Why is this base here? What strategic purpose is it serving? That strategic purpose, as explained to me by Captain Hieu, was “It’s here to protect the airfield.” Well, what’s the airfield here for? “To resupply the base.”

It struck me, a 26-year-old infantry captain, as “We’re here because we’re here.” Now that was a bit unfair. The airfield allowed you to have other operations going on and it established a presence in the valley.

Even so, “We’re here because we’re here” was a metaphor for the war? We kept adding troops, we kept adding bombers, we kept adding fighter planes. There were 3,000 advisers when I got there, and my contingent brought it up to well over 11,000. But it wasn’t enough. We kept adding, adding, adding, and we deceived ourselves into thinking we were making more progress than we actually were.

It finally came to a halt when General [William] Westmoreland asked for yet another large tranche of soldiers, and Lyndon Johnson said, “That’s it. No more.” We had 540,000 there then [1968].

It had become a much broader war, not just sandal-clad Viet Cong guys running around. The North Vietnamese Army had come in. No matter what we did, we could not stop them from coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. We could not stop them from re-equipping or resupplying their forces.

We kept hoping we could draw them out into fixed battle, where they could be defeated. But they had a better strategy than we did. They picked their place and time. They came out during the Tet Offensive [at the end of January 1968] and caused a lot of damage. They lost huge numbers, but they understood it wasn’t a military operation. It was a political operation. They were not aiming to kill Americans. They were aiming to kill the American spirit. And they succeeded.

You and the other advisers in the early years were sent to Vietnam by Presidents Dwight Eisenhower and John Kennedy. Did Eisenhower and Kennedy make a mistake in starting the movement of U.S. troops to Vietnam? No. It started out as a reflection of the Cold War with the Soviet Union and China and our desire to help this small country defend itself against insurgency and a foreign invasion [from North Vietnam]. When I went over there in 1962, I felt I was doing something noble, and that’s what President Kennedy thought when he was sending us over.

The original mission was to advise the South Vietnamese on how to defend themselves. Time passes, and you have the Gulf of Tonkin incident [in August 1964, when North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked a U.S. destroyer]. Lyndon Johnson is the one who made the fateful decision to add more. Then you have the Marines and the Army starting to come in 1965. But I can’t put that onto Eisenhower or Kennedy.

Eisenhower wouldn’t help the French [who controlled Vietnam in the 1950s and wanted the U.S. military to join a fight against Vietnamese seeking independence] when he was asked. He was very careful about getting into foreign entanglements. There has been speculation that if Kennedy had lived, he would not have continued. I don’t know what he would have done.

As I ended my year as an adviser in ’63, I realized we had been stomping around in the forest and chasing people who were not catchable. We were starting to do things we thought would help us, such as destroying crops. We were walking through planted areas with chemical sprayers, spraying manioc plants and rice plants. Then we started burning hooches. I thought, the hooches can be rebuilt in a day, and this will be replanted. So where is this all going?

By the time I left in 1969, after my second tour, it was clear that we had gotten into a war we didn’t fully understand. It was not a war of communism vs. capitalism or totalitarianism vs. democracy. It was a war of nationalism. The North Vietnamese were determined to reunite Vietnam into one country.

Do you think we could have beat the North Vietnamese and won the war? They were prepared to put every life at risk. They were truly willing to lose whatever it took to win. I remember seeing a statistic that said their birth rate is higher than any kill rate we can impose upon them. This will go on forever. And they were going to be sustained by outside powers.

During World War II, the objective was to take terrain and hold it until the enemy surrendered. In Vietnam, it was search and destroy, kill large numbers of the enemy in an area, then pull back. Could U.S. forces have applied the take-and-hold approach to get a clear victory? My own view was—notwithstanding what many of my fellow veterans have said—that we could not have done that. We were never prepared to put in what would have been required. We also were supporting a regime that had lost some of its legitimacy. We had coup after coup. It wasn’t a government that had the support of the people any longer. People were suffering economically, suffering from the NVA and the VC.

And what would we have done? Occupy the whole country with a million American soldiers and keep them there? Remember, we were not invading Vietnam. We were fighting a Vietnamese war in South Vietnam. There was a border, the 17th parallel. So they [the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong] had a sanctuary. They kept pouring in support, pouring in troops, taking massive casualties, but kept coming. And we were not seriously bombing them in a way that hurts.

I love air power. I used air power in every conflict I have been seriously involved in. But I’m also an infantry officer. If you can’t hold and control the ground, you haven’t won. Planes fly back to their bases. Ships are at sea. If you want to really win a war, you’ve got to have a guy with a rifle.

In World War II we bombed Germany into total destruction, but it wasn’t until the Russian army entered Berlin and we met the Russians at the Elbe that the war was brought to a conclusion. In Japan, we sent an army to take control after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After we left in 1973, could the South Vietnamese have prevailed against the North’s invasion if the United States had continued to fund them? That’s the view of a lot of Vietnam veterans—that it was the Congress who lost this war. I can’t buy into that. By that point, it didn’t make any difference whether we could have [won] because the American people had made a decision. We are a people’s army. And the losses were hundreds a week. I do not think that the American people had the will to fight the kind of war that the North Vietnamese were going to fight.

You have to remember what was going on in the country at the time. I arrived home [from the first tour] the day Kennedy was killed, and then five years later his brother was killed. Martin Luther King was killed April 4, 1968. The country was really coming apart. We had racial problems. The vice president resigned in disgrace and then the president got caught in Watergate and he resigned in disgrace. There was still a Soviet Union. There was still a People’s Republic of China—maybe Nixon had been there, but it wasn’t yet the China it is today. We had a recession. The counterculture was sweeping across the country. We had to do something. And one of the things we had to do was get out of the war.

So what do we as a country say to the families of those who died there? What did they die for? Did they die in vain? They served their country. And when the country called on them, or conscripted them, they didn’t shrink from it. You should be proud of the fact that your loved one answered the call.

We regret all of the losses, all of the 58,000. I lost three of my CCNY classmates, including one of my dearest friends, Tony Mavroudis. But that’s war. It was the first one we ever lost like that. It was a biggie. But we came out of it. America is a country of enormous resilience.

What are the lessons of the Vietnam War? The major lesson I used as chairman, national security adviser and secretary of state was to advise leaders: Make sure you understand what you’re getting into. Don’t fight a war with somebody who has a greater investment in it and a greater cause than ours. That’s manifested itself in other things I have said over the years, such as “You break it, you own it.”

The second lesson is once you decide something is worth it and you’re prepared to invest military force, in addition to political and diplomatic efforts, make sure you don’t just send a few advisers and think that will work. This has become known as the Powell Doctrine, but it really is classical military doctrine. If you look at the basic principles of war, the two captured in my thinking are objectives and mass.

First, what is the objective? What are we trying to do? Have we analyzed the enemy, the terrain, the weather and all the other aspects of the situation? An objective should have a political basis to it. Why are we doing this politically? Not just can we do it militarily.

And once you’ve got the objective, the other part is mass. What I call decisive force. People are forever calling it Powell’s “overwhelming” force doctrine. I used that word once, and I realized it was a bad word. Never used it again. “Decisive” means make sure you put enough in so that you will prevail, will have a decisive outcome.

Desert Storm is a perfect example. Panama is an even better example. When Manuel Noriega killed one of our people [a Marine stationed in Panama] and assaulted some others, we had a plan ready. We’ve got 13,000 stationed there already, and let’s send another 13,000 in. We have a [Panamanian] president in waiting, hiding under a bed. He’s been elected, so once we take the country over, we’ve got a guy to swear in that same day. We got rid of the Panamanian army, but we brought it right back, reconstituted it, which is what we did not do in Iraq many years later, to my distress.

We didn’t take charge of Iraq. We disbanded the army, which was a huge strategic error, compared to what we did in Panama, where we rebuilt it as fast as we took it apart, which was what we were supposed to do in Iraq. But that was not the decision made in the Pentagon. We did not secure the country. And it goes south for four years until President Bush orders a surge, but the surge should have come at the beginning, not in the end. And so we’re still in this conflict. Iraq’s not yet a success in my judgment.

Should a corrupt dictatorial leadership, like South Vietnam’s, deter us from joining forces with a country even though we have a common enemy? It should deter us, but deter doesn’t mean stop. It means there is a yellow blinking light, and we ought to be very, very careful about getting deeply involved in these places. But sometimes the politics and the strategic situation require you to do so.

After the Vietnam War, how did you and the other young career officers size up the condition of the U.S. Army and determine any changes that needed to be made? The advisers who went in were very professional. The Army and Marine Corps troops that started deploying in ’65 were very professional. They had good leadership. But over the next several years, we started to lose a lot of people and were rotating a lot of people with one-year tours and six-month command tours.

The quality of the force deteriorated. We started to have drug problems. There were some fragging problems, not as many as people suggested, but I used to be careful in my own hooch, move my bed around because there was the potential to be fragged by your own troops.

The young soldiers coming in reflected the society they were coming from. Support for the war was dropping. Racial tension was rising. Conscription was seen as a problem.

When I was in Korea as a battalion commander, we were at the beginning of the all-volunteer force. It hadn’t been funded adequately, so the youngsters we were getting tended to be not high school graduates. Judges had said to some: Go to the Army or go to jail. A high percentage did not speak English. The challenge was immense, but it was the most rewarding year I’ve ever had—getting these kids in shape.

I told them, “If you do drugs, I’m going to throw you out.” Every morning I got up with them, and we ran 4 miles and got them tired. And we kept them tired all day long, so when night fell they were too tired to get into too much trouble.

We constantly had competitions. Best clerk, best mess hall, best anything, to make sure that every youngster who had never been successful in high school had a chance to win. Some of my officers had wives who came in to teach these kids, get them GEDs, send them home better than we got them.

A couple of years later I was a brigade commander in the 101st, in ’76 to ’77. By then you could see the quality improve because we were taking 95-98 percent high school graduates.

The real end to this period and the beginning of a new era was Ronald Reagan. He and my boss, Cap Weinberger, put tons of money into the military and restored pride. And from then on it’s been a fabulous force.

What was your favorite music from the 1960s and ’70s? In the ’60s I was pretty much in the forest, but Marty Robbins’ “El Paso” was one of my favorites. I knew Elvis Presley. I liked his music. I really remember the songs of the early ’70s because I was in Korea freezing my butt off in this metal hut that I lived in. AFN [American Forces Network] would come on in the morning and play “Rock the boat, don’t rock the boat baby,” by the Hues Corporation. Also Fifth Dimension songs, and there was “Hotel California” [by the Eagles].

That era was noted for some unusual clothing styles. What did you wear when you were off duty? I could not keep up with the troops. They were wearing bell-bottoms. And the black troops had some sharp clothes that you wouldn’t believe. Go look at some of those old Super Fly movies, and you’ll see what they wore. There’s a picture of me shaking hands with President Nixon, and you’ll see my hair is a lot longer. I had something of a fro, but not a full fro, and I was wearing a hideous double-knit suit.

Which political or military leaders do you admire most? Lincoln was a remarkable political and military leader. And Washington, who lost over and over but learned as he lost and became a brilliant strategist. Eisenhower was not noted as a great tactician in his early years, but he was a great staff officer and a great strategist. He went from colonel to four stars in three years and got command of Europe.

Which political or military leaders do you admire most? Lincoln was a remarkable political and military leader. And Washington, who lost over and over but learned as he lost and became a brilliant strategist. Eisenhower was not noted as a great tactician in his early years, but he was a great staff officer and a great strategist. He went from colonel to four stars in three years and got command of Europe.

One person I should mention is George Marshall. Roosevelt had to decide who was going to go to Europe to lead the invasion. Marshall badly wanted it, and Roosevelt gave it to Eisenhower, who had been a junior officer under Marshall. Roosevelt said, “George, I could not sleep well at night if you were not here.” And Marshall said, “Yes, sir.” And that was the end of it. “Yes, sir.” He was that kind of selfless leader that I have always admired.

In almost every major war in American history, someone who served in it became president. How come one of the longest wars, Vietnam, never produced a president? We didn’t win. None of the generals emerged from Vietnam with political reputations.

Do you ever regret not having run for president? No. I found other ways to serve our nation and my fellow citizens.

Residence: McLean, Va.

Education: City College of New York, bachelor’s degree in geology; U.S. Army Command and Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kan.; MBA, George Washington University; National War College, Fort McNair, Washington, D.C.

Military service: June 1958-September 1993, assignments included: • Platoon leader, Company B, 2nd Armored Rifle Battalion, 48th Infantry Regiment, Germany • Executive officer and commander, Company D, 2nd Armored Rifle Battalion, 48th Infantry Regiment, Germany • Commander, Com- pany A, 1st Battle Group, 4th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Brigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized), Fort Devens, Mass. • Adviser, 1st ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) Infantry Division, Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam • Instructor, U.S. Army Infantry School, Fort Benning, Ga. • Executive officer, 3rd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment, 11th Infantry Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division (Americal), Vietnam • Division G-3 (operations staff officer), 23rd Infantry Division (Americal), Vietnam • Operations research analyst, Office of the Assistant Vice Chief of Staff, Washington • Commander, 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, Eighth U.S. Army, Korea • Operations research systems analyst, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Manpower and Reserve Affairs), Washington [Gerald Ford, president; James Schlesinger, defense secretary] • Commander, 2nd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, Ky. • Senior military assistant to the deputy secretary of defense, Washington [Jimmy Carter, president; Harold Brown, defense secretary] • Assistant division commander, 4th Infantry Division (Mechanized), Fort Carson, Colo. • Deputy commanding general, U.S. Army Combined Arms Combat Development Activity, Fort Leavenworth • Military assistant to the secretary of defense, Washington, [Ronald Reagan, president; Caspar Weinberger, defense secretary] • Commanding general, V Corps, Germany • Assistant to the president for national security affairs (national security adviser) [Reagan] • Commander in chief, Forces Command, Fort McPherson, Ga. • Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Washington [George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, presidents]

Civilian government service: secretary of state, January 2001- January 2005 [George W. Bush, president]

Today: Current activities include: • Chair, board of visitors, Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership, City College of New York • Founder and chairman emeritus, America’s Promise Alliance, a group of organizations with programs to help youths graduate from high school and succeed in life • Board of directors, Council on Foreign Relations • Board member, Smithsonian Institution’s African American Museum of History and Culture • Chairman, Eisenhower Fellowships, an international program for emerging leaders in various fields • Advisory and board positions with venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, and Bloom Energy

First published in Vietnam Magazine’s August 2016 issue.