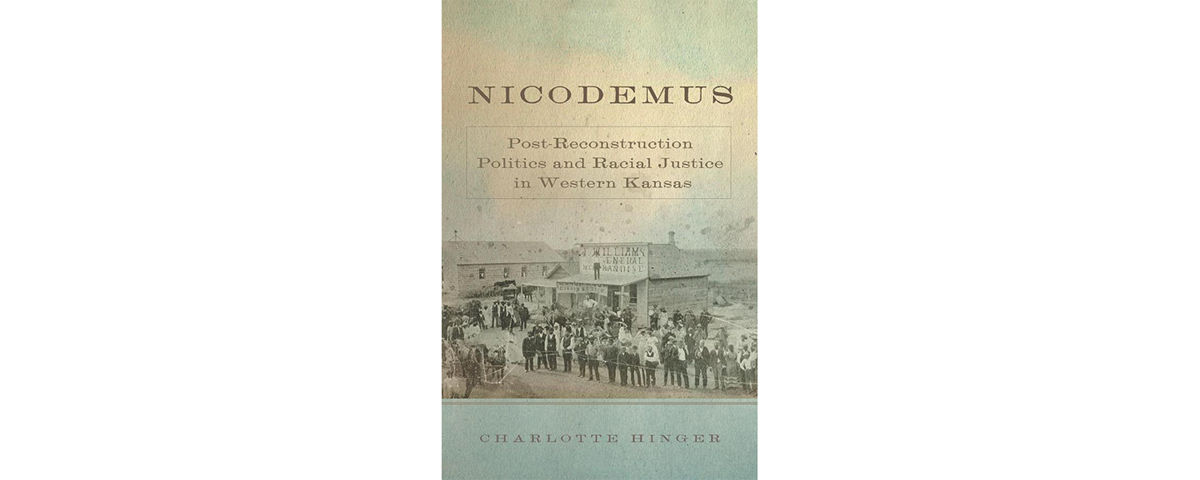

Nicodemus: Post-Reconstruction Politics and Racial Justice in Western Kansas, by Charlotte Hinger, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2016, $29.95

The 1877 end of Reconstruction was a severe blow to black American prospects of achieving the political and social equality that had seemed so tantalizingly within reach in 1865. White Democratic backlash in the South returned great numbers of them to a state of near slavery in all but name. Like a good many other Americans seeking a way out of the hopeless position in which they stood, thousands of blacks headed west, where land, opportunity and a chance to change their fortunes beckoned. Particularly attractive to them in 1878 was Kansas, forever associated with the name of John Brown and offering the prospect of free land to those willing to till it. Amid the exodus the town of Nicodemus stood out for its all-black population and for the general zeal with which its populace pursued farming, business, education, journalism, politics and numerous other endeavors of which so many white Americans claimed they were incapable.

Other authors have written about Nicodemus, but here Charlotte Hinger focuses on the politics and ideology that developed in the intellectually fertile environment it provided. She selects three prominent homesteaders who embodied three different approaches toward achieving equality and how they applied their philosophies in and beyond the town. Abram Thompson Hall Jr. believed in “racial uplift,” each individual setting an example through personal achievement. Edward Preston McCabe, the first black state official elected in Kansas, promoted politics and legislation as the key to achieving nationwide equality. John W. Niles, a former slave and one of Nicodemus’ founders, possessed innate oratory talents that helped him outwit a cadre of lawyers in his own criminal case, then become the first black to persuade the U.S. Senate to consider a petition for slave reparations. As Hinger follows the careers and contributions of these men in the context of both their era and the century that followed, she concludes that each of their approaches remains relevant and continues to influence American attitudes, black and white, for better or worse.

—Jon Guttman