The game known as baseball definitely developed in the eastern United States, but it spread westward across the Mississippi River far sooner than most people think. Exact dates when baseball “nines” first appeared out West are sketchy, but then the very origins of the game on the Eastern seaboard have long been debated.

One thing is certain: Future Civil War Union General Abner Doubleday did not invent baseball in Cooperstown, N.Y., in 1839—a myth not only accepted but also promoted by Major League Baseball for many years. Truth is, no one “invented” baseball. Europeans were playing stick-and-ball games centuries before there was a United States, and those games came across the Atlantic with immigrants. In the 1820s and 1830s folks in Philadelphia, New York and New England were playing several variations of “base ball” (originally spelled as two words). In 1845 Alexander Joy Cartwright Jr. was among the organizers of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, which played first in Manhattan and then across the Hudson River at the Elysian Fields, outside Hoboken, N.J. Cartwright and associates published a set of rules and regulations that became the foundation of modern baseball.

Cartwright, who had worked as a bank clerk, bookseller and volunteer fireman in New York City, left there in March 1849 to join the California Gold Rush and reportedly brought those rules, as well as balls and bats, on his journey across the untamed frontier. Along the way, according to his transcontinental diary, he taught the Knickerbocker brand of baseball to fellow 49ers, soldiers, saloonkeepers and even a few Indians. Thanks to the research of Monica Nucciarone, author of the groundbreaking 2009 book Alexander Cartwright: The Life Behind the Baseball Legend, we now know that it was practically a Doubleday-sized myth. Cartwright did not mention baseball in his original 1849 diary. It seems in the 20th century a grandson produced a typescript of the diary in which he introduced baseball references to help his ancestor land a spot in the Baseball Hall of Fame (which indeed happened in 1939). Nucciarone also found little evidence that Cartwright played baseball in his short time in San Francisco or instituted the playing the game in Hawaii after sailing to Honolulu in August 1849.

In the 1850s baseball remained primarily an Eastern pastime, though in Minnesota Territory in 1857 (the year before statehood) an organized ball club formed in Nininger City (now a ghost town in Dakota County). By the end of the decade baseball was said to be the most popular team sport in New Orleans. On February 22, 1860, two San Francisco squads, the Eagles and the Red Rovers, played the first recorded baseball game in that city. Texas has long been a hotbed for football, but teams were playing baseball in Galveston and other Lone Star locations prior to the Civil War. In 1861 sports enthusiasts formed the Houston Base Ball Club and began promoting the game locally, much as Cartwright had done back in New York.

During the Civil War, soldiers—mostly Yankees, though some Rebels—played baseball during battlefield lulls and in prison camps (including the Confederate-run Camp Ford in Texas). “The New Orleans boys also carried base balls in their knapsacks,” Will Irwin wrote in a 1909 Collier’s Weekly article. “A few of them found themselves in a Federal prison stockade on the Mississippi. They formed a club.” Union soldier George Putnam recalled that once during a baseball game in Alexandria, La., enemy troops attacked, placing the outfielders in mortal danger. The left fielder and right fielder managed to get back to the dugout, but the Rebels shot and captured the center fielder before the Yankees could repel the attack. After the war, soldiers and others from the East and Midwest spread their love of the game across the Western frontier. For instance, as George Kirsch notes in his book Baseball in Blue and Gray, “a contingent of ‘Rocky Mountain Boys’ played the ‘New York game’ in Denver.”

In May 1866 the first known baseball team in the Northwest formed in Oregon—the Pioneer Baseball Club of East Portland. The Portland squad soon recorded a 77–46 victory over the Clackamas Club. That same year the Oakland Live Oaks played their first game in San Francisco in a league known as the Pacific Base Ball Convention. A year later two Texas teams faced off on the San Jacinto Battlefield, near Houston, on April 21—the anniversary of Sam Houston’s 1836 victory over Antonio López de Santa Anna’s Mexican army that won Texas its independence. The teams involved were obviously more influenced by the recent Civil War than by the Texas Revolution: In a lopsided contest (as was San Jacinto itself), the Houston Stonewalls blasted the Galveston Robert E. Lees, 35–2.

Also in 1867, up in Kansas, the Frontier Baseball Club formed in Leaven-worth, the game quickly spreading to Lawrence, Topeka and other towns. On May 17, 1868, Captain Albert Barnitz wrote his wife from Fort Hays in western Kansas: “Have not been to church, because there was none to attend—but in lieu of this all the officers, including half a dozen from Fort Dodge who are here on a visit, participated in a social game of base ball!” That July, Barnitz was at Camp Alfred Gibbs, where officers celebrated the Fourth of July by playing baseball. At some point in his career famed gambler/lawman Wild Bill Hickok reportedly rooted for the Kansas City Antelopes. Legend has it he even umpired one of their games while wearing a pair of six-shooters.

In 1869 the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first true professional baseball team, its players drawing salaries (the high being $1,400 a season to George Wright, the brother of player-manager Harry Wright). That first season the Red Stockings posted a perfect 57–0 record against generally overmatched amateur teams. Late that summer, the Red Stockings traveled to California via steamboat and the newly completed transcontinental railroad. In San Francisco, the Wright brothers and colleagues defeated the Eagles, the Atlantics and the Pacifics, usually by at least 40-run margins, and The San Francisco Chronicle praised the Red Stockings’ athletic ability as well as their “large and well-turned” legs. On the return trip they played two games at Omaha, Neb. First, they rolled to a 65–1 victory in a game called after seven innings because the home team’s only catcher had to leave early, and the next day they humbled another local nine, 56–3, in a five-inning romp.

In October 1869, days after the Red Stockings had crossed back through Utah Territory, the Eureka Club of Salt Lake City took on soldiers from Camp Douglas in an exhibition game. Corinne, a railroad town in the territory, formed a baseball club the following March and won its first game, 90–50, over the Box Elder Club. On June 21, 1870, the Deseret News ran a challenge from a Salt Lake City team: “We the Ennea Base Ball players of this city, considering ourselves champions of the territory, are willing to meet any other club within the limits of the territory who wish to dispute the claim and contest for the same.” Corinne rose to the challenge, beating the Ennea elite in a three-game series that summer.

Also in 1870 the Harvard baseball team traveled by railroad as far west as St. Louis to play other college teams and local clubs. In 1872 a baseball squad from New Orleans went on a Texas road trip—traveling by stagecoach to play teams in Austin, Dallas and Waco. The following year, H Company, 7th U.S. Cavalry, formed the Benteen Base Ball Club in Nashville, Tenn., named in honor of company commander Captain Frederick Benteen. While in Dakota Territory between 1873 and 1876, the club played other military squads as well as civilian teams. On July 31, 1874, during Lt. Col. George Custer’s Black Hills Expedition, the Fort Lincoln Actives defeated the Fort Rice Athletes, 11–6, at the site of what is now Custer, S.D. “The enlisted men,” according to historian Brian Dippie, “whiled away the long summer day playing a game of baseball—a genuine Black Hills ‘first,’ including a dispute over the umpire’s impartiality.”

In 1875 the Mississippi River town of Keokuk, Iowa, fielded a team in the National Association of Professional Baseball Players. The National Association became the National League the next year, but the Keokuk Westerns did not become a part of it. In 1876 (the same year Custer met his match at the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory and drifter Jack McCall shot Hickok from behind in Deadwood, Dakota Territory) only one of the original eight National League teams—the St. Louis Brown Stockings—was from the West, joining teams from New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Cincinnati, Hartford and Louisville. The Brown Stockings folded after the 1877 season, but in 1882 a St. Louis team in the American Association, the newly formed “other” major league, picked up the nickname (soon shortened to the Browns). When that league folded in 1892, the St. Louis Browns joined the National League, changing its name to the St. Louis Cardinals in 1900. An American League team called the St. Louis Browns played from 1902 to 1954, at which time it moved east and became the Baltimore Orioles.

Early pro ball also caught on elsewhere in Missouri. In 1884 the Kansas City Cowboys played in the Union Association, a designated major league at the time. In 1886 a team using the same nickname played a one-year trial in the National League, finishing with just 30 wins and 91 losses (36 of the latter by a single pitcher, Stump Wiedman). Next season the league dumped the Cowboys in favor of the Pittsburgh Alleghenys (today’s Pirates). A third version of the Cowboys resurfaced for two losing seasons (1888 and 1889) in the American Association. In 1902 the Kansas City Cowboys were back in business as one of the original teams of a new minor-league American Association. The Kansas City Athletics played in the majors (American League) from 1955 to 1967 (between homes in Philadelphia and then Oakland), while the expansion Kansas City Royals club was born in 1969.

Among the first minor leagues to field “Western” teams was the Northwestern League of 1879. While Rockford (Ill.) lay east of the Mississippi, the other three teams played on the west side of the river—in Omaha, Neb., and Davenport and Dubuque, Iowa. The Dubuque Rabbits, sporting red stockings, finished first in the uncompleted 36-game season. The Omaha Mashers, wearing green stockings and anchored by pitcher Jim “Grasshopper” Whitney, were 8–12 when they folded. In 1885 the Omaha Omahogs played in a Western League that again saw team and league fail. But the league was resurrected in 1886. That year the Lincoln (Neb.) Tree Planters finished dead last behind the Leavenworth (Kan.) Soldiers, Topeka (Kan.) Capitals, Leadville (Colo.) Blues, St. Joseph (Mo.) Reds and champion Denver Mountain Lions.

Still, most baseball played out West in the 19th century remained amateur or semipro, including the barnstorming games of the Nebraska Indians. Founder and promoter Guy W. Green recruited several of his players from the Omaha and Winnebago reservations; nine of the 12 players on his first club in 1897 were Indians. On June 25 of that year the squad traveled to Lincoln and trounced the University of Nebraska team, 18–12, before an enthusiastic crowd. Through 1914 (Green left in 1907) the Nebraska Indians played across the country, often calling to mind the atmosphere of a Wild West show. The team was good, too, reportedly posting a record of 1,237 wins, 336 losses and 11 ties.

Many towns and forts—including Fort Union in New Mexico Territory, Fort Apache in Arizona Territory, Fort Russell in Wyoming Territory and Fort Missoula in Montana—proudly formed teams in the closing decades of the 19th century. At Fort Sill in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), where baseball made its appearance as early as the 1870s, Indians sometimes played alongside soldiers, although its most famous internee, Apache leader Geronimo, favored racing his horse over watching baseball. One day, according to author Angie Debo, Geronimo set up a race and finally tracked down his jockey at a baseball diamond just as the young man hit a home run. Geronimo reportedly chased the slugger around the base path before taking him to the racetrack.

In the coal-mining town of Krebs, Indian Territory, on July 4, 1882, players used sacks of hay and cans for bases as 300 people watched the home team defeat nearby Savanna, 35–4. In 1889 future Hall of Fame pitcher Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity starred for Krebs and helped spread interest in the game to places like Tahlequah, Muskogee, Eufaula, Checotah, Vinita and Wagoner. The land rush that prompted the formation of Oklahoma Territory in 1890 (Indian Territory remained the eastern part of what in 1907 would become the state of Oklahoma) also scattered baseball diamonds in new places, including Guthrie, Stillwater, Kingfisher and Oklahoma City. Clothing merchant Seymour C. Heyman started Oklahoma City’s first professional baseball club in 1902, but it was another two years before the Mets, part of the Southwest League, became the first team there to play a full season of organized baseball. Subsequent minor league teams in Oklahoma’s capital city have included the Indians, Senators, Boosters, 89ers and RedHawks.

Minnesota also took up town ball after the Civil War, the North Star Club of St. Paul (just east of the Mississippi) starting a century-long rivalry with a club in Minneapolis (just west of the Mississippi). In late August 1876 in St. Paul, the James-Younger Gang, according to Homer Croy’s 1949 book Jesse James Was My Neighbor, “went out to see a baseball game between the St. Paul Red Caps and the Winona Clippers.” Those were indeed independent Minnesota ball clubs of the time, although researcher Jack Koblas says it was “highly unlikely but not impossible” the outlaws were there. That September 7, of course, the gang was in Northfield, Minn., making a disastrous attempt to rob a bank that landed the three Younger brothers—Cole, Bob and Jim—in Stillwater Penitentiary.

A “gentlemen’s agreement” kept blacks out of the National League but not out of the national pastime (Minnesota, for example, had both white and black ball clubs). In 1875 the all-white Winona Clippers fielded a black pitcher/second baseman named W.W. Fisher. And in 1883 John “Bud” Fowler, a black player who hailed from Cooperstown, N.Y., saw action at various positions for the Northwestern League team in Stillwater (presumably not within sight of the imprisoned Younger brothers’ cells). Minnesota claimed its first major league team in 1884, when St. Paul played nine games in the Union Association (a league that lasted just one season). But the state didn’t host another team in the majors until 1961, when the Washington Senators moved to Minneapolis and became the Minnesota Twins.

In the Far West, the semipro California League and the original Pacific Coast League launched in the 1870s. Each had its ups and downs, including failures and restarts. A new Pacific Coast League (PCL), comprising teams in Los Angeles, Oakland, San Francisco, Sacramento, Portland and Seattle, started up in 1903 and was recognized as an official pro league the following year. Utah’s Salt Lake Bees joined the PCL in 1915 (back in 1901, Salt Lake and three other Utah ball clubs played in the short-lived Inter-Mountain League). The PCL still exists. The current California League was founded in 1941. It wasn’t until 1958 that modern-day Major League Baseball teams operated west of St. Louis—after the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles and the New York Giants to San Francisco. Today the Far West is also home to the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, Oakland Athletics, San Diego Padres and Seattle Mariners.

Down in cattle country, University of Texas ballplayers first squared off against their Texas A&M rivals in 1884, a decade before meeting on the football gridiron. Professional minor league baseball came to the Lone Star State in 1888 when John J. McCloskey (1862–1940) founded the still-active Texas League. Major League Baseball became part of the Texas landscape in 1962 with the arrival of the Houston Colt .45s (later the Astros). In 1972 the second iteration of the Washington Senators moved to Arlington and became the Texas Rangers.

Over in New Mexico Territory in 1880, the first semipro team in Albuquerque took the field on the fairgrounds. Organizer W.T. McCreight had once played for the major league St. Louis Browns and chose to call his new team the Albuquerque Browns. Organized baseball made its Southwestern debut in 1915 (three years after New Mexico and Arizona became states) with the Rio Grande Association. Albuquerque and Las Cruces, N.M., fielded teams, as did El Paso, Texas, and Douglas, Phoenix and Tucson, Ariz. That league, too, was a one-season wonder. New Mexico has yet to claim a Major League Baseball franchise, though the Albuquerque Dukes operated for years in the Pacific Coast League, and today’s Albuquerque Isotopes are the Los Angeles Dodgers’ top farm team.

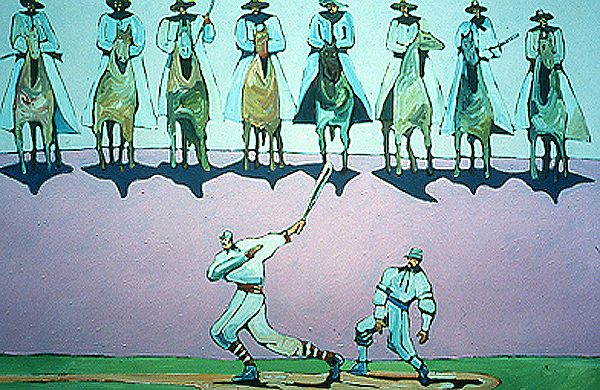

Baseball also took root during Arizona’s territorial days. Around Tombstone in 1882, the same year Wyatt Earp carried out his vendetta against the Cowboys, a civil engineer from Massachusetts named George S. Rice had baseball on his mind. First, he started a team called the San Pedro Boys at his Boston and Arizona Mill, following that up with the Tombstone Base Ball Association squad. After much practice, his “tossers” opened their season on May 12 with a loss to a Tucson club, but the organization was persistent, playing ball for four decades. In 1909 the Phelps Dodge Mining Co. opened Warren Ballpark in Bisbee for the enjoyment of its employees; it remains in use today. On June 27 of that year, in its first game, the semipro Bisbee club beat a visiting team from El Paso, 8–3.

Bisbee later joined the “outlaw” Cop-per League of 1925–27. The league, whose four original teams hailed from Douglas, Fort Bayard (N.M.), El Paso and Juarez (Chihuahua, Mexico), was outside the control of Major League Commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis and included players he had banned from organized baseball for gambling. For instance, Chick Gandil and Buck Weaver, who had both played for the infamous 1919 Chicago “Black Sox,” saw action for Douglas in 1925. Bisbee and Chino (as well as Hurley and Santa Rita, N.M.) joined the next season, but the league soon shut down—as usual for financial reasons. After World War II, Arizona joined Florida as a host for Major League Baseball spring training exhibition games. Arizona’s Cactus League continues to operate, and since 1998 the National League Diamondbacks have called Phoenix home.

Farther north, students at Colorado College in Colorado Springs organized a baseball team in 1880. The Colorado State League formed in 1885, with teams in Colorado Springs, Leadville, Pueblo and Denver. The next year the Denver Mountain Lions won the Western League title with a 54–26 record. Other Denver minor league teams through the years have included the Mountaineers, Grizzlies, Solis, Gulfs, Zephyrs and Bears. The Mile-High City finally landed in the majors with the Rockies in 1993.

By the 1870s soldiers were playing ball at Wyoming Territory forts, and towns like Laramie and Cheyenne had organized teams. The latter sported such names as the Black Stockings, Nonpareils, Benedicts, Eclipse, Bachelors and Indians. In 1912 the Cheyenne Indians played organized minor league ball ever so briefly in the Class D Rocky Mountain League. One of the teams in that four-team league was from Pueblo, Colo., but it moved to Trinidad, Colo., on June 8 and then to Cheyenne on June 28. Other Cheyenne pro teams continued to call themselves the Indians, but they were not part of the minor league system. As early as 1887 Montana formed its own state league, which operated on and off. In 1900 the league featured the Butte Smoke Eaters, Anaconda Serpents, Great Falls Indians and Helena Senators. Two years later the Senators and the Butte Miners were playing in the Class B Pacific Northwest League.

In May 1889 in Dakota Territory (North Dakota and South Dakota would become the 39th and 40th states, respectively, that November), Aberdeen merchant L. Frank Baum formed the Hub City Nine, supplying players with uniforms and equipment from his store, Baum’s Bazaar. Hub City won both the state championship and the newly formed South Dakota Baseball League crown, but the club lost money, and Baum—who would write The Wizard of Oz a decade later—announced he was through with baseball. He told the Aberdeen Evening Republican in October 1889, “I expended no little time and worked hard for the success of the organization but ran out of money and time.” During the Ghost Dance trouble a year later, frightened Indian agent Daniel Royer brought nephew Lewis McIlvaine, a farm boy from Huron, S.D., to Pine Ridge to teach the Lakotas how to play baseball. The plan was to distract them from their dancing; it didn’t work, and McIlvaine left the reservation before the powder keg exploded at Wounded Knee in December 1890.

Representing South Dakota in the low-minor Iowa–South Dakota League in 1902 were the champion Sioux Falls Canaries and the Flandreau Indians. Iowa hosted the other four teams, from Sioux City, Le Mars, Rock Rapids and Sheldon. But the league dwindled to four teams and then folded after the 1903 season, and pro ball didn’t return to South Dakota until 1920. The Northern League, which formed in 1902, included four North Dakota teams (Cavalier, Devil’s Lake, Fargo and Grand Forks), as well as the Crookston Crooks of Minnesota and a squad representing Winnipeg, Canada. An independent Northern League still exists today.

Pro baseball was slow in coming to Nevada, but the first organized game dates back to 1869 when Carson City bested Virginia City, 81–31. By the early 20th century many Nevada towns and fraternities had organized teams. The copper companies sponsored baseball nines and built diamonds in places like Ruth, Cooper Flat, Ely and McGill; the Northern Nevada Railroad also fielded a team. Minor league ball didn’t come to the state until 1947, when the Las Vegas Wranglers and Reno Silver Sox played in the sprawling Sunset League.

By the time pitcher-turned-entrepreneur Albert Goodwill Spalding took a group of professional ballplayers on a world tour in the winter of 1888–89, the game was already well established in Hawaii, where Alexander Cartwright was still living if not reminiscing about the game he did not invent. King Kalakaua entertained Spalding’s players on a stopover in November 1888, but no game took place. “Everybody wanted to witness the game,” Spalding wrote, “but, alas, it was Sunday. We obeyed the letter and spirit of the law, called the game off and left a lot of disgruntled Americans and disappointed Kanakas [natives], to say nothing of the much-coveted shekels.” But Hawaiians continued to embrace baseball. Near the turn of the 20th century the New York Sun reported, “If the Kanakas persist in their pursuit of the game, we may soon expect to see a team of Hawaiian players traveling through the United Sates, somewhat after the fashion of the Australian cricketers in Great Britain.”

As early as 1893 baseball had even gone to Alaska. “A large number of bats and balls had been brought up from San Francisco by one of last summer’s arrivals,” Frederick Funston wrote in 1894. The future U.S. general had ventured north to work for the Department of Agriculture. “As soon as the ships had gone into quarters, seven clubs were organized and formed into a league to play for the ‘Arctic Whalemen’s Pennant,’ which was a strip of drilling nailed to a broomhandle.” In the first game, played “in the brief twilight of an arctic December day, with the mercury 38 degrees below zero,” the Roaring Gimlets defeated the Pig-Stickers, 62–49. The games went on all winter. “The provision in the bylaws that a club refusing to play on account of weather forfeited its position caused one game to be played at 47 degrees below zero,” said Funston, “and often during blizzards the air was so full of flying snow that the outfielders could not be seen from the home plate.”

While jet transport has made travel relatively easy for today’s 30 Major League Baseball teams, Eastern ball clubs still gripe about tough Western road trips (even if Hawaii and Alaska are not on the schedules) and vice versa. Fans in the East—especially the ones not privy to sports updates on ESPN.com or other Web sites—complain when box scores from West Coast ball games are absent from the morning editions of their hometown newspapers. Fans in the West, of course, have little sympathy, especially those who have to drive long miles to catch Major League Baseball action live in places like Seattle, Denver and Phoenix. That is not to dismiss the joy of minor league ball or bush league ball anywhere; those less-glamorized, more intimate games seem closer to baseball’s roots and to the diamonds in the rough that once cropped up in America, even on its wild frontier.

Wild West Editor Gregory Lalire played two seasons of bush league baseball in the late 1970s for Ronnie Martin’s Hobbs A’s in a West Texas–New Mexico semipro league.