Georgia Gov. Joseph E. Brown telegraphed a frantic plea from Atlanta to Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Richmond on June 28, 1864. He begged the chief executive to send reinforcements to the Army of Tennessee, which was being steadily forced toward Atlanta through the mountains of northern Georgia.

“I need not call your attention to the fact that this place is to the Confederacy almost as important as the heart is to the human body,” he said.

“I fully appreciate the importance of Atlanta,” Davis responded, but he had no troops to spare; his dwindling military forces had too many other points to defend.

Brown’s analogy was apt. Three railroads converged within Atlanta like arteries, carrying everything that sustained the South’s war for independence. The city itself was a major industrial center providing essentials ranging from small-arms ammunition to shoes.

In another message on July 4, Brown again insisted Atlanta must be saved—“The whole country expects this, though points of less importance should, for a time, be overrun.”

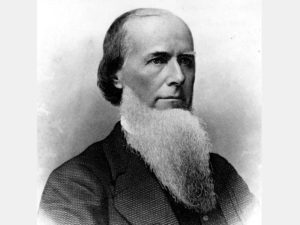

Davis probably had to suppress a rueful chuckle. From the very beginning of the war, Brown had fought with him over control of Georgia’s troops. The Confederate government was only three years old, but the governor thought it was already getting too big for its britches. The military draft instituted in April 1862 was unconstitutional and despotic in his eyes, demanding states send troops elsewhere that they might need to defend themselves.

Oh, Georgia did its share, all right, sending upward of 100,000 of its sons to serve the Confederacy, most going to Virginia. But Brown was so intent on keeping enough of them at home that the Georgia militia became known as “Joe Brown’s Pets.”

By the summer of 1864, however, the blue-clad wolf was howling at Atlanta’s door and Brown was desperate to save the self-proclaimed Gate City to the South. Atlanta, according to The New York Times, was “at once the workshop, the granary, the storehouse and the arsenal of the Confederacy.” The city and its environs were “of incalculable value.”

Situated near the border between the mountains in northern Georgia and the Piedmont’s rolling hills, the city was brimming with contradictions—its four-term mayor James Calhoun, for example, was a Unionist at heart but a faithful servant of the Confederacy.

Though Atlanta’s strategic importance was as obvious as a black bear in a cotton field, the city was the consolation prize in the contest between two armies vying against each other in Georgia that summer. Yet whichever side possessed the prize by autumn would almost certainly win the war, be it Abraham Lincoln and the single nation Unionists or Jefferson Davis and the states-rights-are-supreme secessionists.

A History of Atlanta

Atlanta began in 1837 as a stake driven into the ground in the Georgia wilderness, on a ridge seven miles east of the Chattahoochee River. Stephen H. Long, chief engineer for a proposed railroad to Chattanooga, selected that spot as the southern terminus of what would become the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Settlers drifted in and a community sprang up, appropriately known as Terminus.

The name changed to Marthasville when the town was chartered in 1843, to honor the daughter of former Gov. Wilson Lumpkin, who had been prominent in establishing the railroad. Two years later, the town’s name changed to Atlanta. Various stories claim that was the feminine form of Atlantic or a reference to the swift, powerful huntress of Greek mythology or the middle name of Lumpkin’s daughter.

A second railroad, the Georgia Line, arrived from Augusta in 1846, and a third was completed in 1854. Money rolled in with the rails, and Atlanta boomed like no other Southern city. Its inhabitants were proud that their town was frequently compared to New York. On the eve of the Civil War, the city was Georgia’s fourth largest, with some 7,750 whites, 1,900 slaves and about two dozen freemen of color. The enslaved proportion of Atlanta was low in a state where slaves accounted for 44 percent of the total population.

The victory of antislavery Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party in 1860 led slave-owners to conclude “the honor, safety and independence of the Southern people are to be found only in a Southern Confederacy,” as the “Southern Manifesto” of December 1860 proclaimed. Atlantans for the most part didn’t favor secession, but Georgia voted to secede, the fifth state to go.

When Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to put down the Southern rebellion the following spring, Georgia became critical to Southern success in the war. The state’s 68,000 farms produced 700,000 bales of cotton in 1860, and a sizable textile industry existed. No other state in Dixie could match the production of Georgia’s 33 mills; at their wartime peak, they turned out more than a half-million yards of cloth a week. Atlanta became the Confederacy’s second-largest clothing depot, after Richmond.

Georgia’s location far behind the war’s front lines made it the Confederate Ordnance Bureau’s logical choice for a munitions center as well. Existing iron foundries, machine shops and rolling mills were converted to produce war materiel. The Confederate ironworks turned out artillery, armor plate and rails. Atlanta Machine Works produced forges for rifling muskets.

The Atlanta Arsenal was Georgia’s largest. Employing nearly 5,500 workers, it was the primary ordnance supplier for the Confederacy’s second-largest military force, the Army of Tennessee. Between March 1862 and war’s end, the arsenal supplied more than 46 million percussion caps and 9 million rounds of ammunition—and thanks to its railroads, Atlanta could deliver those tools of death wherever they were needed.

To merely call Atlanta a rail center understates its true position. More than 1,400 of Dixie’s 9,200 miles of track lay within Georgia, a total second only to Virginia, and the three railroads converging at Atlanta connected with the entire South.

The Western & Atlantic wound north through the mountains to Chattanooga to meet up with rails from Nashville and northern Alabama. Feeding off the W&A at Dalton, Ga., the East Tennessee & Georgia snaked toward Knoxville; near Kingston the W&A met the Rome Railroad that rolled west to the port town of Rome, where the Etowah River flowed into the Coosa.

Traveling southwest from Atlanta was the Atlanta & West Point. At two locations it joined a line called the Macon & Western, which penetrated southern Georgia and carried salt, fish, beef, pork and fruits from Florida. More significantly, the Macon & Western intersected the Central Line, the South’s only contiguous railroad linking the Eastern Seaboard with the Mississippi Valley.

The road east from Atlanta, the Georgia Railroad, traveled to Augusta on the South Carolina border. From there, the Augusta & Savannah and the South Carolina railroads rolled on to Savannah and Charleston, respectively. Other lines branched off the South Carolina Railroad to carry trains through North Carolina to the Shenandoah Valley, Petersburg and Richmond. The South’s various roads used different rail gauges, requiring frequent transfers from one train to another, but the rail systems that merged in Atlanta could get troops, war materiel and consumer goods, animals and messengers to any state of the Confederacy east of the Mississippi and some points beyond.

The railroads also made Atlanta a destination for thousands of wounded soldiers and for refugees fleeing Union armies in other parts of the Confederacy. For a time Emilie Todd Helm, half-sister to Lincoln’s wife, Mary Todd, was among them.

Young Atlanta was already a rambunctious teenager compared to the South’s older, more genteel cities, thanks to its rapid prewar population growth. But its unprecedented population influx during the war blew the doors wide open.

Not enough lime could be procured to eliminate the stench from the city’s outhouses. Rail passengers had to weave their way among stretchers of groaning, flyblown wounded at the depot. Deserters and stragglers wandered in. Crime soared. Anything not nailed down was fair game for thieves; if it was nailed down, they would simply look for a crowbar to pry it loose.

Petty thievery wasn’t the worst crime. The city was horrified when a beautiful young widow who had fed Memphis for Atlanta was found raped and strangled in her bed. No one was ever charged. Shopkeepers and thieves, society matrons and destitute widows, plantation owners and slaves, soldiers and deserters all pressed together in Atlanta’s streets. But someone was coming who would make its present troubles seem pale.

The Last Link of the Confederacy

In the summer of 1864, the York Herald declared Atlanta “The last link which binds together the southwestern and northeastern sections of the rebel Confederacy. Break it, and those sections fall asunder.”

Breaking that link was the job of “Uncle Billy,” Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, who had already led troops at Shiloh, Vicksburg and Chattanooga.

When Ulysses S. Grant was made commander of all Union armies in March 1864, he named Sherman his replacement in charge of the Military Division of the Mississippi—an area from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River.

Sherman assembled at Chattanooga a force comprised of the Army of the Cumberland under Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas (61,000 officers and men, and 9,000 cavalry), the Army of the Tennessee under Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson (24,000) and the Army of the Ohio commanded by Maj. Gen. John Schofield (13,000, including a cavalry division). Combined, they boasted about 250 artillery pieces. About 10,000 of the 110,000-man total would have to remain at Chattanooga to guard Sherman’s railroad supply line from Nashville.

When Sherman’s force crossed the Georgia line in early May, his orders from Grant were to “break up” the opposing army, then “get into the interior of the enemy’s country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can against their war resources.” If he couldn’t destroy the enemy’s army, he had to at least keep it from sending reinforcements north to where Grant was engaging Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Grant’s instructions made no direct mention of Atlanta, but both men had been supply officers and knew the rail line from Nashville to Atlanta was crucial to the Georgia campaign. Sherman’s line of march, therefore, would be aimed toward the Gate City.

His first and most important order of business, however, was to “break up” the opposing army. Enemy armies, not cities, were now the primary goal— Grant intended to destroy the South’s ability to make war. Nashville had fallen in February 1862; the rebellion had continued. New Orleans had fallen. The rebellion continued. Memphis, Vicksburg, Chattanooga—none of those victories had ended the war. As important as Atlanta was, Sherman’s most important target was the Army of Tennessee, strongly entrenched at Dalton under the leadership of a new commander.

Georgia in the Civil War

General Joseph Johnston—“Old Joe,” his soldiers called him—had been sentenced to command the Army of Tennessee when its former leader, Braxton Bragg, resigned following the Confederate debacle at Chattanooga in late November. “Sentenced,” because the paranoid Johnston suspected Jeff Davis and a circle of anti-Johnstonites had sent him to Georgia in order to destroy his career, which, frankly, hadn’t been all that stellar so far despite a respectable record as a member of the U.S. Army before the war.

When he commanded in Virginia, the Federals had advanced to within a few miles of Richmond before Johnston was wounded, Robert E. Lee was put in command and the Yankees were driven back. Assigned to supervise the Department of the West, Johnston showed little imagination or vigor in the post.

Now at Dalton, he had been handed a dispirited, hungry army that had seen its blood shed on too many fields for no gain. In the soldiers’ view, even its stunning rout of the Army of the Cumberland at Chickamauga the previous September had been tossed aside like an old chicken bone when Bragg chose to lay siege to Chattanooga rather than crush the disordered and demoralized foe huddled below the mountains. Lincoln’s War Department sent Grant, victor of Fort Donelson, Shiloh and Vicksburg, to end the siege. Bragg’s army, its morale stretched as thin as its lines on the heights above Chattanooga, broke on Missionary Ridge and fed into Georgia.

Johnston had worked since January to restore morale, secure supplies, build up his army and create a series of defensive positions in the mountains of northern Georgia. But Jefferson Davis didn’t want Johnston to fight from defensive positions. Misled as to the true condition of the Army of Tennessee, Davis wanted Johnston to recapture eastern Tennessee and carry the war to Sherman’s army. With about 55,000 men and 154 guns, Johnston saw no hope for initiating an attack. Old Joe hoped instead to draw Uncle Billy into costly assaults on fortified positions, and then finish off the weakened Northern horde.

Sherman was having none of it. He had surveyed northern Georgia for the U.S. Army 20 years earlier and knew the terrain better than Johnston did. In the following weeks he repeatedly maneuvered the Southern forces out of one strong position after another, making only one ill-advised frontal assault at Kennesaw Mountain.

By mid-July he had also maneuvered Johnston out of a job. The Confederate army had fallen all the way back to fortifications just outside Atlanta. Davis and his military adviser—Bragg, whom Johnston had replaced—concluded Old Joe would not fight outside entrenchments. On July 17 they replaced him with a subordinate, feisty John Bell Hood, who’d had his left arm mangled by shrapnel at Gettysburg and then lost his right leg at Chickamauga.

Hood attacked a portion of the Federal force on July 20 while it was crossing Peach Tree Creek a few miles north of town. Desperate fighting, much of it hand-to-hand, diminished Hood’s army by nearly 5,000 men; Sherman’s by less than 2,000. The attack failed.

Still, Atlanta mocked Sherman’s attempts to capture it. The year before, Col. Lemuel P. Grant, a native of Maine who had become the chief engineer of the Department of Georgia, devised a system of defenses around the city. Initially 10–12 miles of fortifications were built a mile from the city’s center, with trenches, palisades and 17 redoubts holding five artillery pieces each. A second line was built behind the first; more forts were added and lines extended.

Local planters were ordered to lend slaves to provide the labor. Thousands of enslaved workers arrived in Atlanta to saw timbers, dig trenches in the red Georgia clay and cut down all trees on the hills in front of the breastworks so defenders would have clear fields of fire. They toiled in the Georgia heat, subsisting on barely enough food to keep them alive. Some managed to slip away; a few were hidden by courageous Unionists on the outskirts of the city.

When Sherman arrived in 1864, he faced the most heavily fortified city south of Richmond. Assaults would be suicidal—he had lost enough men using those tactics at Vicksburg and Kennesaw—but if he couldn’t capture the city, he would destroy it.

The first artillery shell went whistling into Atlanta on July 20, the day of the Battle of Peach Tree Creek. For more than a month, hundreds of shells, some as large as 33 pounds, daily damaged buildings, plowed up yards, exploded overhead and killed or wounded civilians and soldiers. Citizens went about their business, and thieves still made off with whatever they could. Atlanta refused to surrender—and time was running out.

Northern states would hold elections in October for state officials and congressional representatives. The presidential election would follow on November 8. Both would be referenda on Lincoln’s policies, and the North was war-weary. More than three years of carnage had not restored the Union, and many Northerners’ support for the struggle had dimmed because they believed Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation made it a war in which white men were dying to free black men. That might play well in the abolitionist stronghold of New England, but not in states west of the Ohio River. Even Pennsylvania was teetering. Northern Democrats were offering the nation an “honorable peace,” promising to negotiate an end to the war and possibly even restore the Union, with slavery intact. Their candidate was the former commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George McClellan.

Lincoln himself doubted he would win re-election. Newspaper reports of Grant’s early battles in Virginia had grossly exaggerated their effect on Confederate forces, creating unrealistic hopes in the North. That euphoria seeped away with the blood oozing from Grant’s long stream of ambulances. Lee was slowly being forced back toward Richmond, but he remained unbeaten and continued to prove that he could turn seeming defeat into stunning victory.

Sherman, too, was providing Northern newspapers with extensive casualty lists, though not on the scale of Grant’s. The Battle of Atlanta on July 22 cost 8,500 Confederate casualties and 3,600 Union—including James McPherson. The battle at Ezra Church, on July 28, produced 3,500 Confederate casualties, but just 600 Union.

Sherman’s men hadn’t yet captured Atlanta, but they were far closer to that prize than Grant was to Richmond. The outcome of November’s election, it seemed, lay on Sherman’s shoulders— an ironic twist of fate, considering he personally would accept “a sentence to be hanged and damned with infinitely more composure than to be elected chief executive of this nation.”

Sherman Takes Atlanta

All the railroads into Atlanta had been severed except the lines south of town. On August 26 the city woke to a sound it had not heard in more than a month: silence. No shells came shrieking over the rooftops. No musketry crackled. When Confederates ventured out of their trenches, they found a large portion of Sherman’s works abandoned. Had “the vandals” been starved out and gone home?

Hardly. Sixty thousand Federals were slipping around Atlanta to cut Hood’s last line of supply. The Confederate commander learned they were tearing up tracks at Jonesboro, and sent two corps on a night march to attack them. When the Battle of Jonesboro was over, 2,000 of Hood’s men lay dead or wounded. Sherman had lost fewer than 200.

Even “give them the bayonet” Hood had to acknowledge he could no longer defend the city. On the night of September 1, an explosion rocked Atlanta, sending flames into the sky that were visible two miles away. A teenage girl, Mary Rawson, awoke to see the night sky “in a perfect glow,” and flaming rockets bursting overhead. “Sparks filled the air with innumerable spangles,” she recalled.

Unable to save 28 boxcars loaded with munitions, staff officers set fire to them as Hood evacuated his army. The resulting explosion fattened every building for hundreds of yards around, twisted iron rails and reduced railroad ties to splinters.

The next day, Mayor James Calhoun led a party of the city’s Unionists to surrender Atlanta.

“Atlanta is ours and fairly won,” Sherman telegraphed Lincoln on September 2. Throughout the North cannons roared and church bells clanged to celebrate the victory, while in Dixie diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut wrote, “Atlanta, indeed, is gone. Well, that agony is over. …No hope, but we will try to have no fear.”

The butcher’s bill for the summer’s campaign in Georgia came to 31,600 dead, wounded and missing for the Federals and nearly 31,000 for the Confederates. For Unionists, the sacrifice was worth it. The fall of Atlanta, plus naval success at Mobile Bay, Ala., and Union victories in the Shenandoah Valley buoyed Northern confidence in Lincoln’s war policies.

The Union and Confederate commanders in Georgia both failed in their primary goal—destruction of the opposing army—but if Atlanta was a consolation prize, it was a grand one. The question of whether Johnston’s more conservative tactics might have held the city until after the Northern elections fueled postwar debate.

Sherman evacuated all civilians from the city, claiming he intended to fortify the town. But in actuality, he was going to fulfill his orders to “get into the interior of the enemy’s country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can against their war resources.”

He planned to make Georgia howl.

Gerald D. Swick has previously written about the Civil War for American History, Wonderful West Virginia and America’s Civil War. For more on the contest for Atlanta he recommends The Bonfire: The Siege and Burning of Atlanta by Marc Worthman and Atlanta 1864 by Richard M. McMurry.