A Portuguese king sought to glorify his military exploits through the art of tapestry.

IN THE 1470s KING AFONSO V OF PORTUGAL (1432–1482) commissioned a series of tapestries from the workshop of Flemish weaver Pasquier Grenier, the preeminent commercial weaver of the late 15th century.

Medieval and Renaissance monarchs and merchant princes often commissioned tapestries, but Afonso’s tapestries were unusual. Instead of portraying heroic deeds from mythology, the Bible, or ancient history, the four works known as the Pastrana Tapestries celebrated the Portuguese king’s capture of two Moroccan ports in 1471—victories that earned him the name “Afonso the African.”

PORTUGAL’S INVOLVEMENT IN NORTH AFRICA had begun a generation before Afonso, with the conquest of the Moroccan trading center of Ceuta in 1415. It was a dramatic military triumph, as the city fell in a single day. Once captured, however, Ceuta became a liability. The Portuguese had envisioned the city as a gateway to the luxury trades of silk and spices from Asia, the abundant wheat of North Africa, and the gold that traveled across the Sahara from the Sudan to North Africa. Instead, Ceuta was an isolated possession surrounded by hostile territory.

Rather than abandoning the port as a bad investment, Portugal decided to use it as a base for further expansion. In 1436 a Portuguese expedition sailed with the goal of capturing Tangier, a strategic port on the Strait of Gibraltar. Led by two of King Duarte’s younger brothers, it was an abject failure. Unlike the Ceuta expedition, which had been planned over several years, the 1436 expedition was put together rapidly, undermanned, and inadequately armed. The Portuguese forces met fierce resistance from the city’s defenders, who were quickly reinforced by soldiers from neighboring cities. The invasion ended in a humiliating treaty that allowed the Portuguese to evacuate their soldiers but required them to leave a royal prince, the Infante Dom Fernando, in Tangier as a hostage.

King Duarte’s sudden death in 1438 left six-year-old Afonso V the new king of Portugal. No new African expeditions sailed from Portugal during the young king’s troubled minority. But the failure of the expedition against Tangier and the need to avenge Dom Fernando, who had died in captivity in 1443, were always in the background as unresolved problems, and once Afonso reached his majority, he became obsessed with conquering Tangier.

His first expedition, in 1458, was a limited success. Afonso and his forces captured Kasr es-Seghir, a small town between Ceuta and Tangier. The garrison at Kasr es-Seghir successfully withstood two sieges by Muslim forces but was unable to extend Portuguese control beyond its walls. Two subsequent sieges of Tangier, led by Afonso himself in 1463 and 1464, failed altogether, largely because the Portuguese army was unable to keep reinforcements from reaching the besieged city.

On August 15, 1471, Afonso sailed again for Morocco, with a force of 400 ships and 30,000 soldiers—larger than any force Portugal had previously fielded against North Africa. His plan was to first capture the port city of Asilah, which would give Portugal control of territory on both sides of Tangier, and then march against Tangier itself.

When Afonso’s troops landed near Asilah, they found Morocco torn by civil war. Asilah’s governor, Muhammad al-Shaikh, was away, besieging Fez in a bid for control of the sultanate, and had left the city poorly defended. The Portuguese bombarded it for three days and then stormed the walls. By the time al-Shaikh returned, Asilah was already in Portuguese hands.

The capture of Tangier was anticlimactic. When news of the Portuguese victory reached Tangier, its citizens decided to evacuate rather than suffer a merciless assault like the one that had felled Asilah. On August 18 the Portuguese marched into the city unopposed.

On his return, Afonso commissioned four monumental tapestries to commemorate his North African victories.

FIFTEENTH-CENTURY TAPESTRIES WERE COMPLEX works of art, woven with fine wool yarn and silk and silver or gilt-metal thread. Only the richest and most powerful could afford them. Tapestries were a status symbol, commissioned to display the wealth and importance of their owners. Afonso’s tapestries had an additional purpose: to record his triumphs for posterity.

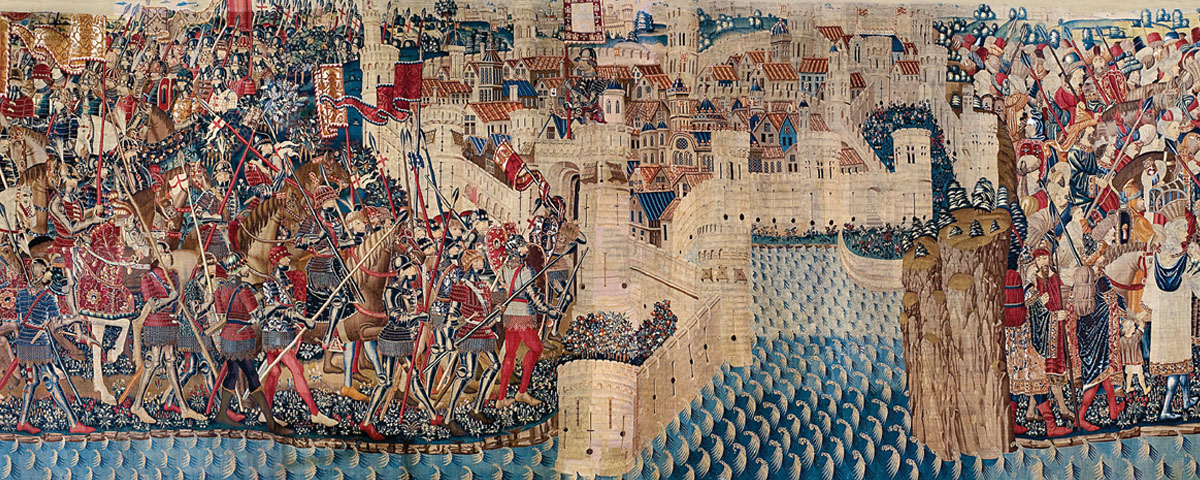

Together, Afonso’s tapestries total 49 yards in length. They contain hundreds of figures of knights and foot soldiers set against a stylized backdrop of ships and fortresses. The tapestries are unmatched in their detailed depiction of arms and armor used in 15th-century warfare, including the construction of brigandines, the placement of lance rests, the form of helmets, and the shapes of spear points and sword hilts. Both artillery and handheld firearms are prominent in the tapestries, reflecting the changing nature of warfare at the time.

Throughout the series King Afonso and his son, Prince João Manuel, are distinguished from the mass of the Portuguese force by their luxurious armor and garments: both their brigandines and horse armor are covered in patterned fabrics that stand out against the monochromatic brigandines worn by their troops. They are further identified on each tapestry by the location of the royal banner with the king’s personal emblem—a spinning waterwheel spraying droplets, with the word jamais (never) at its center—which Afonso chose to express his eternal sorrow over the death of his first wife, Isabel of Coimbra.

The tapestries depict four separate scenes from the 1471 campaign: the landing at Asilah, the siege and assault of Asilah, and the capture of Tangier. Each tapestry is a complex composition in its own right; together, read as a sequence from left to right, they give us a panoramic view of the campaign.

The first tapestry depicts the landing of the Portuguese troops in Asilah, dividing the narrative into three parts and using the same left-to-right movement that carries across the tapestries as a whole. The left side of the first tapestry shows the arrival of the Portuguese fleet off the coast near Asilah. In the center Afonso and João dominate the foreground, overseeing the landing. Behind them, oared boats ferry soldiers from the ship. Each boat bristles with banners and weapons. Bodies of drowned soldiers wash ashore, almost unseen in the crowded field of the tapestry—a reminder that some 200 knights and foot soldiers were lost in the operation. In the upper right, king and prince advance toward the city walls at the head of their troops, who are crowded shoulder to shoulder, giving the effect of a huge military force. By contrast, the Muslim defenders of Asilah are spread thinly along the walls of the besieged city, which looks more like a Northern European city than “the most opulent Moorish city” described in the Latin banner across the top. That’s not surprising, given that the artisans and weavers who produced the panels would have had no model of a North African city to draw on.

The second tapestry, which depicts the siege of Asilah, is relatively static. The composition is shaped by three concentric ovals that contain the besieging force within their lines. The besieged city stands at the center, surrounded by the Portuguese army, whose soldiers are armed with muskets, pikes, and crossbows. The oval formed by the city wall is paralleled by the wooden palisade that surrounds the Portuguese army—a structure that was built to prevent reinforcements from neighboring cities (a lesson learned from previous expeditions against Tangier). Between the palisade and the city walls, the Portuguese force is divided into two sections by a central bombard, one of several artillery pieces that are aimed at the city along a third rough oval. Afonso and João, on horseback, bracket the action from positions on the far left and right. Unlike the Portuguese troops, who are crowded together, the defenders of Asilah are spread thinly across the walls of the city. Besiegers and defenders alike are caught in a quiet moment before the battle begins.

The third tapestry shares the same basic structure as the second, but quiet is replaced by frenzy. The defensive palisade and artillery are no longer visible because the Portuguese army is at Asilah’s walls. Portuguese soldiers wield naked swords and raised muskets. Some scale the walls, meeting raised scimitars and spears in the hands of the city’s defenders. The walls are masked by the abundance of figures involved in the assault, pressed so tightly together that there is not an open inch in the tapestry.

In the final tapestry, which depicts the surrender of Tangier, the action is once again divided into three parts. At the left, the Portuguese army, unaccompanied by either king or prince, marches on Tangier, which had occupied the national imagination for 35 years. The march is more a triumphal procession than a military advance. The city sprawls across the center of the tapestry, empty but for a single Portuguese soldier, larger than life, who holds the national banner above the battlements. On the far right, pushed into a small section of the tapestry, the inhabitants of Tangier evacuate their city, clutching a few possessions. In the foreground, a woman carries an infant in one arm and leads a small child with the other. Neither Portuguese nor Moroccans are armed, making it clear that this was a bloodless victory.

Commissioning the Pastrana Tapestries was the final step in Afonso’s African career. Having avenged Dom Fernando’s death and captured the long desired city of Tangier, Afonso the African ignored Africa for the rest of his reign and turned his attention to diplomatic relationships with Spain. He died in Sintra in 1481.

THE TAPESTRIES DID NOT REMAIN IN PORTUGUESE HANDS. At some point, probably during Afonso’s lifetime, they became possessions of the Duchy of the Infantado in Spain, perhaps as a gift from the king or perhaps taken as booty after the Battle of Toro (1476), in which Afonso was defeated by the Spanish monarchs Isabella and Ferdinand, putting an end to his attempts to seize the Castilian crown in the name of his second wife, Juana la Beltraneja. In 1667 the heir to the Duchies of Pastrana and the Infantado donated the tapestries to the Collegiate Church of Pastrana, from which they take their name. MHQ

PAMELA D. TOLER writes frequently about history and the arts. She is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War (Little, Brown and Company, 2016) and is currently working on a global history of women warriors.

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2017 issue (Vol. 30, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Threads of History

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!