To this day the U.S. Naval Airship USS ZMC-2 remains unique in the history of lighter-than-air craft. Most airships fall under one of three basic construction formats: rigid, non-rigid or semi-rigid. However, the ZMC-2 employed a completely different construction method with a rigid, metal-covered envelope.

The most common airship type is the non-rigid, epitomized by today’s Goodyear blimps. These airships have a control car supported beneath a fabric-covered gas envelope, the shape of which is maintained by air-filled “ballonets.” The much larger rigid airships had a metal or wooden framework covered with fabric that enclosed a number of separate, individual internal gas bags. German Zeppelins like the doomed Hindenburg were rigid airships. A semi-rigid airship had a gas envelope supported by a rigid wooden or metallic keel. The best-known examples were the Norge and Italia, constructed in Italy during the 1920s and employed for Arctic exploration.

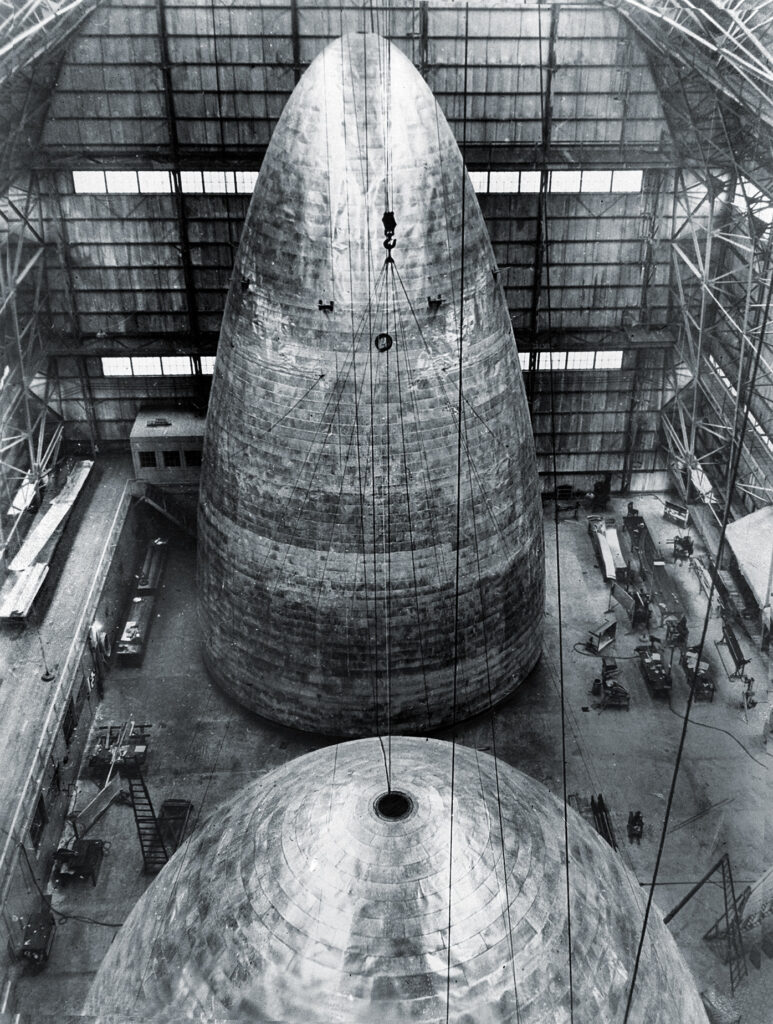

However, the U.S. Navy’s USS ZMC-2, which was designed and built by the Aircraft Development Corporation of Detroit at the Naval Air Station at Grosse Ile, Michigan, embodied a unique approach to airship design that has never been replicated since. The ZMC-2 had a lightweight aluminum interior framework, but instead of fabric its outer covering consisted of thin sheets of Alclad, a lightweight metal of duralumin alloy coated with a layer of pure aluminum to prevent corrosion. The Alclad plates were riveted together by means of a special process developed expressly to render the envelope airtight and prevent gas leakage. In effect, the outer covering of the ZMC-2’s envelope was an Alclad-covered monocoque pressure vessel similar to the fuselages later used on pressurized high-altitude airliners. Unlike rigid airships, the ZMC-2 had no individual internal gas bags—the helium lifting gas was contained entirely within the metal envelope itself. Inside, a pair of flexible air-filled ballonets regulated internal pressure at various altitudes and states of atmospheric pressure, similar to the arrangement employed in non-rigid airships. The ballonets occupied 25% of the internal volume.

The ZMC-2’s envelope was solid, so it did not collapse when deflated. For that reason, the envelope was normally full of air and could not be filled directly with helium because that lifting gas mixes with, rather than displaces, air. As a result, the creators of the ZMC-2 came up with a technique where they first replaced the air inside the envelope with carbon dioxide, a gas that is heavier than, and does not mix with, helium. They then added helium through the top of the envelope while siphoning off the heavier CO2 from the bottom.

The ZMC-2’s designer was Ralph Hazlett Upson, who had previously worked for the Goodyear Corporation developing airships and had won the Gordon Bennett Cup for an international balloon race in 1913. In 1922 Upson established the Aircraft Development Corporation (renamed the Detroit Aircraft Corporation in 1929) with financial backing from a number of Detroit industrialists, including Henry and Edsel Ford, William Stout (creator of the Ford Tri-Motor) and Charles Kettering of General Motors. By 1929 the company had expanded to include controlling interests in other aviation assets such as the Ryan Aircraft, Lockheed and Blackburn Aircraft companies and the Grosse Ile Airport near Detroit.

First flown on August 19, 1929, the ZMC-2 was relatively small because Upson intended it only as an experimental test bed for its revolutionary construction technique. The airship’s naval designation of “ZMC” stood for “Lighter-Than-Air Ship, Metal Clad.”

With a length of 149 feet and a diameter of 53 feet, the ZMC-2 had an internal capacity of 202,200 cubic feet (apparently the “2” in its name referred to this figure) and a useful lift of 750 pounds. (Compare this to the Hindenburg’s internal capacity of more than seven million cubic feet and its lifting capacity of 511,500 pounds.) The ZMC-2 was powered by a pair of 220-hp Wright J-5 Whirlwind radial engines and had a top speed of 62 mph, a cruising speed of 50 mph and a range of 680 miles. There were three crewmembers. (The Hindenburg had 40.)An unusual and distinctive feature of the ZMC-2’s design was that it had eight stabilizing fins arranged radially around the tail, four of which incorporated control surfaces.

Many in the Navy expressed skepticism at the idea of “Tin Blimps.” Even the ZMC-2’s first commanding officer, Lt. (j.g.) Hammond J. Dugan, expressed reluctance to fly in the metal-clad airship. Nonetheless, ZMC-2 confounded the skeptics by completing 752 flights for a total of 2,265 flying hours before being grounded in 1939 and scrapped in 1941. Ironically, the ZMC-2 outlived Dugan, who died in the crash of the USS Akron in 1933.

The ZMC-2’s successful flight record notwithstanding, the Navy remained uninterested in the concept, believing it too small and short-ranged to be useful for the anti-submarine work for which it was intended. In any case the Navy preferred to spend its lighter-than-air budget on the huge, expensive and ultimately disastrous rigid airships USS Akron and USS Macon and later on smaller but more useful and cost-effective non-rigid blimps. The historical record includes no specific explanation of the Navy’s reasoning. Perhaps it considered the metal-clad airship too heavy or too expensive. Maybe it had something to do with the influence of the Goodyear Corporation over the Navy’s lighter-than-air aviation program. It was Goodyear that ended up manufacturing all of the Navy’s other airships, including the rigid behemoths as well as its blimps. Whatever the reasons, it seems a shame since, by airship standards, the ZMC-2 appears to have been one of the more successful examples of the type. But it never received much publicity, and it remains far more obscure than the less successful but more conspicuous Akron and Macon.

Its parent company fared no better. Depression hit the Detroit Aircraft Corporation hard, and it went into receivership in 1931, divesting its heavier-than-air assets to Lockheed and what remained of its lighter-than-air assets under the Metalclad Airship Corporation. Once the Navy expressed no further interest in the concept and no further orders were forthcoming, the Metalclad Airship Corporation soon ceased to exist.