The first American B-17 raid on occupied Europe 75 years ago gave U.S. commanders the confidence to ramp up their daylight bombing campaign.

Early in the afternoon on August 17, 1942, the Wright Cyclone engines of a dozen Boeing B-17E heavy bombers coughed to life at Polebrook Airfield in Northamptonshire, England.

Ground crews made final checks on the big Flying Fortresses of Colonel Frank A. Armstrong Jr.’s 97th Bombardment Group (Heavy) of the U.S. Eighth Air Force’s VIII Bomber Command. In the briefing hut, tension mounted among the young pilots, navigators, bombardiers and gunners. This was it, finally.

The crews had grown nervous and bored waiting for their chance to get into the war, with their morale worn thin from repeated dry runs and a surfeit of dismal weather. They flew several practice missions over England until August 9, when the unit’s combat readiness was announced. The group had been activated on February 3, 1942, at MacDill Air Base in Florida, and trained there. It started its overseas movement on May 15, and the first bomber arrived in Britain on July 1.

Eighteen of the two-dozen available B-17 crews were ordered to prepare for the first all-American bombing raid on Nazi-occupied northwestern Europe. Targets had been selected and the operational machinery set in motion—a prelude to a great American daylight offensive complementing Royal Air Force Bomber Command’s nightly campaign. On August 5, Brig. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, the 47-year-old commander of VIII Bomber Command, and Maj. Gen. Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, leader of the Eighth Air Force, had gone to the London headquarters of Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, U.S. Army commander of the European theater, and presented a plan for their first mission. Ike, who in July had visited Polebrook, the first B-17 airfield in England, quickly approved the plan.

The unpredictable English weather intervened, however, and two missions were canceled. While Eaker grew impatient and his crews nervous, there was restlessness in Washington. On August 14, Spaatz received a cable from General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, the Army Air Forces chief of staff, wanting to know why Eaker’s bombers were still on the ground. Finally, on the evening of August 16, the 97th Bomb Group was alerted for the third time. The weather cleared, and it held.

At 11 the next morning, a relieved Eaker opened an operations conference at his headquarters in a former girls’ boarding school at High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, and ordered VIII Bomber Command’s first combat mission for that afternoon. Their target was the railroad marshaling yards at Sotteville, near Rouen, in northern France—an important traffic center for the shipment of German supplies and personnel, and the site of a repair depot and rolling stock.

The American objective was only 35 miles inland from the English Channel, and therefore well within range of the RAF’s Supermarine Spitfires assigned to escort the dozen Fortresses to the mainland. The group’s six other B-17s were to make a diversionary sweep along the French coast and lure Luftwaffe fighters away from the Rouen area. Eaker’s conference was short because he and his staff had already planned the mission in detail.

Square-jawed, balding and soft-spoken, Ira Clarence Eaker had in just a few months earned the respect of his crews and their British allies. Although he had not seen combat, he was a courageous aviation pioneer. Born in Field Creek, Texas, on April 13, 1896, and raised near Durant, Okla., he was commissioned in the U.S. Infantry Reserve in August 1917 and detached three months later to undergo flight instruction at Penn and Kelly fields in Texas. He won his wings in 1919.

After earning the Distinguished Flying Cross for his leadership as second-in-command of the Pan American Good Will Flight around Latin America in 1926-27, Captain Eaker was assigned as the operations and line maintenance officer at Bolling Air Base in Washington. While there, he was one of the pilots of the Army’s Fokker C-2A trimotor Question Mark who attempted to establish a flight endurance record. The record of 150 hours and 40 minutes in the air was set near Los Angeles in 1929, and Eaker received an oak leaf cluster to his DFC for his participation in the flight.

Promoted to temporary brigadier general in January 1942, he took the helm of VIII Bomber Command in England on February 23. He established close relations with British leaders, including Prime Minister Winston Churchill and RAF Bomber Command’s Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur T. Harris, and set about building an American striking force. According to an Army Air Forces citation, Eaker showed “an unlimited display of initiative, energy, outstanding leadership, and untiring devotion to duty.”

He built his command virtually from scratch. When he and a half-dozen USAAF officers arrived in England, they had no aircraft and no equipment—not even paper clips—beyond what the British supplied them. After the bombers and crews arrived, and when Eaker was confident that his modest force was ready for action, he sent a three-page letter to General Arnold on August 8 affirming his faith in the promise of American air power, specifically daylight precision bombing, which both the British and the Germans had abandoned after severe losses.

The B-17E was the latest Fortress variant then rolling off Boeing’s assembly lines. It featured a sweeping dorsal fin for improved high-altitude performance. It had two power turrets mounting twin .50-caliber machine guns—one just aft of the cockpit and a ball turret under the belly. There was a .30-caliber gun in the bombardier’s nose position, twin .50s in the tail and a .50 in a waist position on each side of the fuselage. The B-17E was the most heavily armed strategic bomber in the world.

Spaatz and Eaker were eager to fly on missions. Eisenhower said they could, but not together. Eventually, persuaded by senior RAF officers that it would be hazardous to the untried American command structure for both him and Eaker to fly in combat, Spaatz backed down.

Eaker felt a strong obligation to see action, and announced that he would go on the first B-17 sortie. As he told actor Ben Lyon, star of the 1930 Hollywood epic Hell’s Angels and a popular wartime BBC radio program, “I don’t want any American mothers to think I’d send their boys someplace where I’d be afraid to go myself.” He also called upon his staff officers to fly “sufficient operational missions in order to be cognizant of the problems facing combat crews.”

After his operations conference early on August 17, Eaker flew to Polebrook, where he was impressed by “the nonchalance of the crews” and their “evident enthusiasm.” At dispersal points around the windswept airfield that afternoon, the camouflaged Fortresses waited. Colorful names painted on their noses included Yankee Doodle, Peggy D., Big Stuff, Baby Doll, Butcher Shop, Alabama Exterminator, Birmingham Blitzkrieg and Berlin Sleeper. Ground crews completed their tasks, and all was ready.

Officers and crews grabbed maps, rode trucks out to the bombers and hoisted themselves aboard. Eaker climbed into the 414th Squadron’s Yankee Doodle as an observer. At 3:14 p.m., the first engine of Colonel Armstrong’s plane, Butcher Shop, emitted a puff of blue smoke. Armstrong would later become the model for the character of General Frank Savage in the classic novel and film Twelve O’Clock High. His copilot was Major Paul W. Tibbets, who would make history three years later at the controls of the famous B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay.

Engines thundering, the dozen B-17s rolled slowly to their takeoff positions, and the USAAF’s first heavy bomber mission of World War II was in motion. Thirty British and American correspondents watched as the planes gathered speed along the runway, and pilots gave thumbs-up signals. The last B-17 had cleared the runway by 3:39 p.m. The bombers assembled over the airfield, climbed to 22,500 feet and headed southward and across the English Channel, escorted by new Mark IX Spitfires. The weather was perfect.

Eaker took a position in the radio operator’s compartment aboard Yankee Doodle, hoping that the mission would succeed. If not, it could inflict a fatal blow on the concept of daylight bombing.

As the bombers passed over the French coast and their escorts turned for home, a British listening post heard a German defense controller radio that “12 Lancasters” were heading inland. Eaker was pleased that the B-17s were keeping good formation, though he felt it could be tighter.

Colonel Armstrong ordered his gunners to be on the alert for German fighters, and Eaker, who had undergone special training to qualify as a gunner, manned the .30-caliber machine gun mounted above his compartment. He had issued a directive earlier stipulating that no one should go on a mission unless he could handle a machine gun. Eaker swung the weapon around and scanned the sunny skies, but no enemy planes appeared.

All went well as the formation neared Rouen at 23,000 feet. The Americans saw no enemy fighters, and only a few desultory bursts of anti-aircraft fire peppered two bombers. The bombardiers could clearly see the complex of rail lines, machine shops and rolling stock from 10 miles out. Bomb bay doors swung open, and Eaker clambered into Yankee Doodle’s bomb compartment to see what it was like in the body of a B-17 in combat. He shivered in the rushing air approaching 35 degrees below zero.

Eaker watched a string of five 600-pound bombs from Yankee Doodle fall over the Sotteville rail yards and then scrambled to a side window to observe the resulting explosions. A high mushroom-like pall of smoke and dirt rose where each string of bombs hit. Eaker believed that the bomb patterns were good, considering the bombardiers’ inexperience. Two bursts flanked the Sotteville roundhouse, four were well spaced along the marshaling yard, two fell short of the target and two fell among the railroad buildings. About half of the formation’s bombs fell directly into the target area. Siding tracks were damaged, railroad cars derailed, two large sheds damaged and a workshop received a direct hit. The B-17s dropped a total of 18½ tons of ordnance that afternoon.

Shortly after the Fortresses pulled away from the target area, three Focke-Wulf Fw-190s climbed up to harass them. Two fighters attacked Birmingham Blitzkrieg, the last bomber in formation. The ball-turret gunner, Sergeant Kent West, fired back and the German planes sped away. Neither side took damage in the half-hearted encounter, and it appeared the Germans were probably taking the measure of the well-armed B-17s.

As Armstrong’s force approached the English Channel on their return to England, Eaker peered from the radio operator’s window and counted the bombers. All 12 were still in formation, though one was lagging and trailing smoke from its left outboard engine. The B-17s droned across the Channel, escorted by clipped-wing Spitfire Vs.

Eaker and Armstrong were elated. Their green crews had hit the target with no losses and only slight damage. The only casualties were a bombardier and navigator in the six-plane diversionary force, who suffered superficial cuts when a flock of pigeons shattered the nose of their B-17 as it headed back to the 97th Bomb Group’s satellite field at nearby Grafton Underwood.

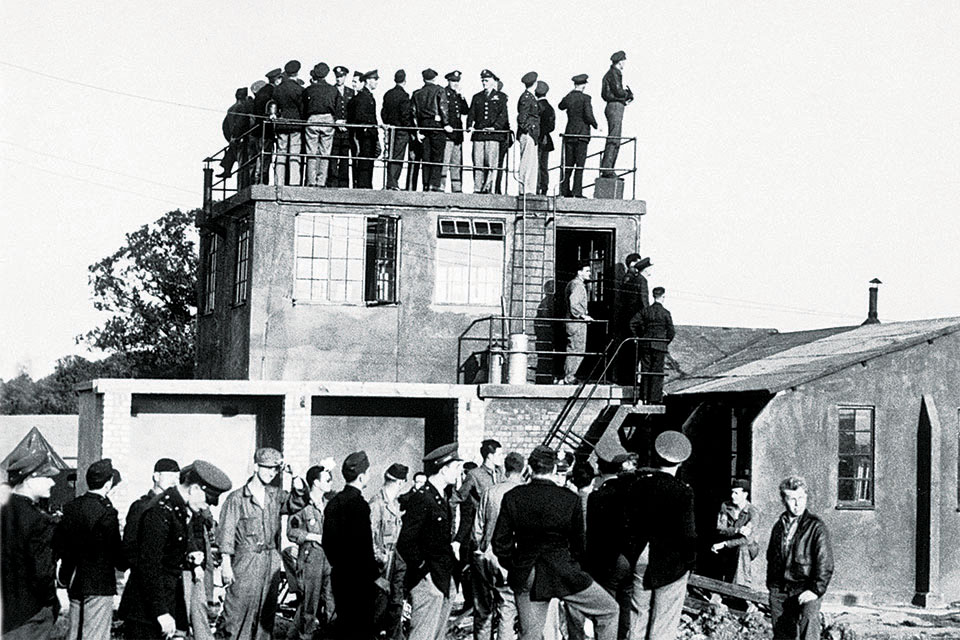

At Polebrook, meanwhile, Spaatz and a crowd of officers, ground crewmen and reporters clustered around the control tower and runway, waiting to welcome the returning bombers. Ambulances and crash crews stood by. Shortly before 7 p.m., an officer on the tower shouted that he could see black specks in the distant sky. The B-17s rumbled in over the field, circled gracefully and touched down one by one.

Grinning and relieved, Eaker, Armstrong and the crews were heartily congratulated before trooping off for a debriefing with welcome doughnuts, sandwiches and coffee. The mission was pronounced a success. All planes had returned safely after bombing their target with creditable accuracy, if not “pickle-barrel” precision. The concept of daylight bombing was alive, although the weather had been ideal and the opposition minimal.

It would be a year before U.S. bombers ventured against targets in Germany, but the August 17 mission was a promising start, heartening Eaker and his British allies, and heralded in the London newspapers. On the day after the raid, the general received a lighthearted telegram from his counterpart and friend, Air Marshal “Bomber” Harris. “Congratulations from all ranks of Bomber Command on the highly successful completion of the first all-American raid by the big fellows on German-occupied territory in Europe,” he said. “Yankee Doodle certainly went to town and can stick yet another well-deserved feather in his cap.”

Reconnaissance photographs showed that almost all the bombs dropped had caused damage. The German transportation network in northern France was hampered, though not critically. Eaker was cautiously pleased. “The raid went according to plan,” he reported, “and we are well satisfied with the day’s work.” But, he added, “One swallow doesn’t make a summer.” He knew that future missions would face serious opposition, and he was aware that Harris and other RAF leaders still harbored doubts about daylight raids.

In a report to Spaatz, Eaker praised the B-17. “I think it is a great airplane” with “excellent defensive firepower,” he stated. “It is too early in our experiments in actual operations to say that it can definitely make deep penetrations without fighter escort and without excessive losses. I can say definitely now, however, that it is my view that the German fighters are going to attack it very gingerly.” The crews, he reported, were alert, though they needed more training in formation and gunnery.

On August 19, VIII Bomber Command launched its second mission. Escorted partway again by Spitfires, the Fortresses bombed the German fighter base at Abbéville, France, to keep the Luftwaffe pinned down while British Commandos and Canadian infantry struggled to breach the coastal defenses in the port of Dieppe. Twenty-two bombers hit Abbéville and returned without loss. The following day, in their third raid, a dozen B-17s bombed the marshaling yards at Amiens and returned safely.

All was going well for Eaker’s flight crews. The small formations hit accessible targets with minimal opposition, and the crews gained valuable experience. Nine missions were flown before a B-17 fell to German gunfire.

But hardship and sacrifices awaited Eaker and his bomber crews as they sortied farther across Europe. The British still advised against unescorted daylight raids, and Churchill tried unsuccessfully to talk Eaker out of the concept. But the British did not interfere; it was thought advisable to let their eager allies learn their own lessons. Meanwhile, they continued to assist by providing bases, equipment and hard-won knowledge.

Supported by General Arnold, Spaatz and Eaker adhered stoutly to the daylight doctrine, but losses mounted alarmingly and by 1943 it appeared that the strategic bombing campaign against Germany was in jeopardy. Disastrous results came when VIII Bomber Command planners aimed for the vital German ball-bearing industrial centers at Schweinfurt and Regensburg.

A complex, coordinated mission was launched on August 17, 1943, against both sites, including the Messerschmitt plant at Regensburg. Of the 230 bombers that attacked Schweinfurt, 36 were shot down. Only minimal damage was inflicted by the B-17s. The Regensburg strike force, led by Brig. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, heavily damaged the Messerschmitt factory but lost 24 planes.

And the situation worsened. A 420-bomber daylight raid against Schweinfurt was planned for October 14, but losses had been so high that only 291 Fortresses could be assembled. Escorted as far as Aachen, the limit of fighter cover, the unescorted bombers were ambushed by enemy fighters and 60 were shot down. Another 138 were badly damaged, and five crashed in England. The day became known as “Black Thursday.”

The Americans had caused a 50-percent drop in ball-bearing production, but the high cost in crews and planes could no longer be borne. Tactics had to be radically changed. Faith among American commanders in daylight missions held firm, but the strategists realized that the B-17s, while heavily armed, still needed long-range fighter escorts if German industry was to be destroyed. Fortunately the North American P-51 Mustang began to arrive in squadrons starting in December 1943, with dramatic results.

Fitted with long-range drop tanks, P-51s conducted their first long-range escort mission on December 13, flying 490 miles from England to Kiel and back. They escorted 228 Fortresses in a raid on February 24, 1944, and only 11 bombers were lost. The following month, P-51s accompanied the bombers to Berlin and back, a round trip of 1,100 miles. Proving to be the most effective U.S. land-based fighters of the war, Mustangs had permitted the resumption of daylight raids.

After laying the groundwork for the American bombing offensive, Eaker succeeded Spaatz as commander of the Eighth Air Force in December 1942. He was designated chief of the Army Air Forces in Britain in October 1943, and headed the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces in January 1944.

Besides the DFC and cluster, Eaker’s decorations included the Silver Star, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Service Medal and cluster, the Air Medal and 11 foreign awards. He died on August 6, 1987, and was buried with full honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael Hull is a former career journalist and British Army veteran. Further reading: Carl A. Spaatz and the Air War in Europe, by Richard G. Davis; and USAAF Handbook, by Martin W. Bowman.

Yankee Doodle Goes to Town appeared in the September 2017 issue of Aviation History Magazine. Subscribe today!