Facts, information and articles about Wild West Outlaws And Lawmen, a prominent figure from the Wild West

Wild West Outlaws And Lawmen: A list of some famous outlaws, gunslingers, bank robbers and gang leaders of the wild west along with the famous lawmen who chased them.

Famous Wild West Outlaws

William “Curly Bill” Brocius

Sam Bass

Thomas Coleman Younger

James B. “Killer” Miller

John Wesley Hardin

Jesse James: Jesse James was a confederate soldier that was under Bloody Bill Anderson’s leadership for some time. After the war he and his brother paid their way by robbing banks, stagecoaches or trains. Read more about Jesse James.

Frank James: Frank James was the brother to the famous Jesse James and also ran the west robbing banks with the gang. He was involved in many robberies including the one in Northfield, Minnesota. Read more about Frank James.

Billy The Kid: Billy The kid was born William Henry McCarty. He was one of the iconic figures of the west and known for robbing banks as well as other establishments with money. Read more about Billy The Kid.

Butch Cassidy: Butch Cassidy was a famous bank robber of the late 1800s. His first offense was near the end of the 1880s and was followed by a string of more serious bank robberies. Read more about Butch Cassidy.

James Younger Gang: The James Gang was the name given to the group that ran with Jesse James and his brother. This group grew from a bunch that had been in the Civil War. Read more about James Younger Gang.

Dalton Gang: The Dalton Gang was a gang of brothers that started out as lawmen in the American West in the late 1800s that turned to become outlaws after have a few payments missed for work they had done. Read more about the Dalton Gang.

Famous Wild West Lawmen

Doc Holliday: Doc Holiday was known for being friends with Wyatt Earp and being fantastic with a gun as well as enjoying gambling. He died of TB in 1887. Read more about Doc Holliday.

Wyatt Earp: Wyatt Earp was a famous sheriff in the Kansas area before moving to Tombstone, Arizona. Several of his brothers and Doc Holiday also moved to Tombstone. Together they lowered the crime. Read more about Wyatt Earp.

Wild Bill Hickok

Bat Masterson

Bill Tilghman

Pat Garrett

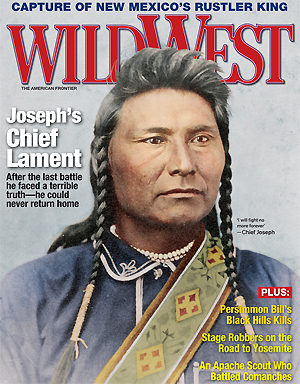

Articles Featuring Wild West Outlaws And Lawmen From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

Gunfights of the Arizona Rangers

‘Men with the instincts of a manhunter could take on a rare challenge remaining in Arizona Territory. Even in the early 1900s bank and train robbers, murderers, rustlers and any other lawbreaker with a fast horse stood a reasonable chance of remaining free from arrest in the vast sweep of sparsely settled land’

Half an hour before midnight on October 23, 1904, Joe Bostwick slipped through the rear door of the Palace Saloon in Tucson, Arizona Territory. His face was shrouded in a red bandana, complete with eyeholes, and he brandished a long-barreled Colt .45. “Hands up!” he shouted.

Four regulars were on duty in the Palace: a bartender, a craps dealer, a roulette dealer and a porter. There were four customers, one of whom, M.D. Beede, slipped out the front door onto Congress Street. Perhaps not noticing the missing customer, the masked desperado nervously ordered, “Throw up your hands and march into the side room.” As the men filed by, the jittery bandit snapped, “Hold ’em up higher—hold up your digits.” Then Bostwick edged toward the craps table, where money lay scattered beside the dice.

Outside on Congress Street, Beede spotted an officer wearing the star badge of an Arizona Ranger. Sergeant Harry Wheeler had just emerged from Wanda’s Restaurant. “Don’t go in there,” Beede said when the Ranger turned toward the Palace. “There’s a holdup going on!”

“All right,” Wheeler calmly replied. “That’s what I’m here for.”

The sergeant pulled his single-action Colt .45 and stepped to the front door of the saloon. Bostwick spotted him and whirled to fire his revolver, but Wheeler triggered the first shot. The heavy slug grazed Bostwick’s forehead above the right eye. Bostwick fired wildly, then Wheeler drilled him in the right side of the chest. Mortally wounded, the stricken bandit groaned and collapsed to the floor.

When interviewed by a reporter for The Tucson Citizen, Wheeler commented: “I am sorry that this happened, but it was either his life or mine, and if I hadn’t been just a little quicker on the draw than he was, I might be in his position now. Under the circumstances, if I had to do it over again, I think I would do exactly the same thing.” Indeed, Wheeler did exactly the same thing—with exactly the same results—in 1907 and again in 1908. And so did other fast-shooting men who wore the star during the brief existence of the early 20th-century Arizona Ranger company.

The Arizona Territorial Legislature created the Rangers in 1901 (various short-lived ranger forces had come and gone in the territory during the 19th century), more than a decade after the 1890 U.S. census had pronounced the frontier closed. For more than seven years Arizona Rangers rode across mountains and deserts in pursuit of cattle rustlers and horse thieves, and, blazing away with Colts and Winchesters, shot it out with desperados in saloons, dusty streets and desolate badlands.

Outlawry was rampant in the territory at the dawn of the 20th century, and Congress consequently refused to consider statehood. Arizona cattlemen, mine owners, railroad officials and newspaper editors pressured Territorial Governor Nathan Oakes Murphy to combat lawlessness with a special force modeled on the famed Texas Rangers. As early as October 1898 an editorial in The Phoenix Gazette decried rustling and proclaimed the need for a band of Rangers: “When such conditions exist, a company of paid ‘Rangers’ are required to stamp out and destroy the characters that bring about such a state of affairs. Let us have a Territorial Ranger Service.”

In early 1901 Governor Murphy presented a Ranger bill to the Republican-dominated 21st Territorial Legislature, which quickly enacted it. The company would be launched on September 1. Murphy asked cattleman Burt Mossman, who had helped frame the Ranger Act, to serve as founding captain. The act authorized a 14-man force—one captain, one sergeant and 12 privates. Two years later the Legislature expanded the force to 26 men—one captain, one lieutenant, four sergeants and 20 privates.

Captain Mossman recruited outdoorsmen for his force—men who could ride and trail and shoot, men who had experience as cowboys or peace officers. Murphy questioned some of the captain’s selections. “Now, governor,” replied Mossman, “if you think I can go out in these mountains and catch train robbers and cattle rustlers with a bunch of Sunday school teachers, you are very much mistaken.”

Men with the instincts of a manhunter could take on a rare challenge remaining in Arizona Territory. Even in the early 1900s bank and train robbers, murderers, rustlers and any other lawbreaker with a fast horse stood a reasonable chance of remaining free from arrest in the vast sweep of sparsely settled land. Rangers were given carte blanche to pursue badmen, authorized to make arrests anywhere in the territory. A Ranger could pin on a badge, saddle up and, in the righteous cause of justice and the territorial statutes, ride up into the mountains and across deserts in pursuit of society’s enemies. And just like in the old days on the frontier, these early 20th-century lawmen sometimes had to match bullet for bullet.

Two of the first Rangers to enlist, Carlos Tafolla and Duane Hamblin, found themselves in a deadly gun battle within weeks of joining the new company. Privates Tafolla and Hamblin had joined a posse in pursuit of the Bill Smith Gang. The men trailed the rustlers into the rugged mountain wilderness of eastern Arizona Territory. At sundown on October 8 the lawmen moved into position to attack the outlaw camp in a gorge at high elevation. Tafolla, Hamblin and Bill Maxwell, an excellent scout, approached the camp from the front in open snow. Maxwell called out an order to surrender.

“All right,” answered Smith. “Which way do you want us to come out?”

“Come right out this way,” directed Maxwell.

Hamblin flattened onto the snow as Smith walked toward the lawmen, dragging a new .303 Savage rifle behind him. Smith suddenly brought up the lever-action repeater and opened fire from a distance of 40 feet. Tafolla went down, shot twice through the torso, while Maxwell, hit in the forehead, died on the spot. Smith darted back to camp as gunfire exploded from both sides. Tafolla gamely worked his Winchester.

Hamblin moved to the outlaw remuda and scattered the mounts, putting the gang afoot. Two outlaws were wounded, and Smith led a retreat into the surrounding timber. With a sudden mountain nightfall the outlaws escaped on foot.

Back in the clearing Tafolla lay on his back, begging for water. Before he died, the Ranger pulled a silver dollar from his pants pocket. “Give this dollar to my wife,” he gasped. “It, and the month’s wages coming to me, will be all she’ll ever have.” Tafolla left three children and his poor widow. His wages for less than a month’s service totaled only $53.15. The Legislature voted Mrs. Tafolla a small pension, and Mossman dutifully brought her the silver dollar.

Mossman resigned after one year to return to the cattle business. The new captain was Tom Rynning, a cavalry veteran and lieutenant with the Rough Riders in Cuba. With his military background, Captain Rynning imposed training and marksmanship practice.

The Ranger Act required that each man carry a single-action Colt .45 revolver and an 1895 Winchester, the first lever-action repeater to use a box magazine instead of the old tubular magazine. Invented by John Browning, America’s foremost genius in arms design, the Model 1895 carried five rounds in the box, with the chamber accommodating a sixth.

Rynning moved Ranger headquarters from Bisbee, a thriving mining town near the Mexican border, to Douglas, a new mining boomtown to the southeast and smack on the border. The Cowboy’s Home Saloon was the center for drinking, gambling and dancing in Douglas. One of the three men who ran the saloon was Lon Bass, a Texan who resented the presence of Rangers and who threatened to kill Private W.W. Webb the next time he entered the Cowboy’s Home.

On Sunday evening, February 8, 1903, the town dives were doing a roaring business when shots went off near the Cowboy’s Home. Privates Webb and Lonnie McDonald heard the gunfire and hustled to the scene.

As the Rangers entered the Cowboy’s Home, Bass sighted them from a rear room where he was dealing monte. He promptly stormed into the main saloon, ordering Webb off the premises and threatening to “beat the face off him.”

Webb responded by whipping his Colt .45 from its holster, cocking it and firing point-blank at Bass. The bullet spun the saloonkeeper around, but Webb thumbed back his hammer and fired again. The second round also went true, hurling Bass to the floor.

“Oh, my God!” he gasped as he went down. Both slugs had torn into Bass’s torso, and one apparently struck his heart. He died on the floor. A few feet away McDonald also sagged to the floor, struck in the midsection by a stray bullet, perhaps a slug that had passed through Bass.

Captain Rynning and Private Frank Wheeler (no relation to Harry Wheeler), patrolling the streets on horseback, quickly arrived at the saloon. So did a couple of other Rangers, along with Town Constable Dayton Graham, who had signed on as the first Ranger sergeant in 1901. Graham arrested Webb, but since there was no jail in Douglas, the constable conveniently directed the Rangers to take their comrade into custody. (Webb did eventually stand trial, but a jury found him not guilty in June 1903.)

Physicians probed unsuccessfully for the slug that struck McDonald. Douglas had as many hospitals as jails, so his fellows carried the bandaged lawman to the two-room adobe that served as Ranger headquarters. Captain Rynning’s house was nearby, and his wife tended the wounded McDonald. The next morning she was horrified at the breakfast the Rangers had cooked for her patient: “a big round steak with a lot of greasy spuds and some gravy that a fork could stand up in.” Instead, Margaret Rynning fed him soft-boiled eggs and other light fare, and McDonald slowly recovered.

One of Rynning’s most notable recruits was Sergeant Jeff Kidder, a superb pistol shot who practiced incessantly with his silver-plated Colt. 45. Normally stationed in Nogales, he was called to Douglas to help control troublemakers on New Year’s Eve 1906. That night Kidder and a local peace officer were patrolling in the vicinity of the railroad roundhouse when they encountered local saloonkeeper Tom T. Woods, who emerged from a rear door and scurried through the rain across the railroad tracks.

“Hold on there!” shouted Kidder. “We want to look at you.” Woods instead broke into a run, then turned and fired a pistol shot at Kidder. The Ranger quickly drew his Colt and blasted out three rounds. One slug slammed into Wood’s right eye, dropping him on the spot. He died later that night.

Another deadly Ranger was Sergeant James T. “Shorty” Holmes, who was stationed at Roosevelt, northeast of Phoenix, where the Roosevelt Dam was under construction. On October 31, 1905, Holmes intercepted Bernardo Arviso, a bootlegger suspected of selling liquor to Indians. Arviso tried to fight his way past Holmes, sparking a furious pistol duel. A government teamster named Bagley tried to help Holmes but caught a bullet in the arm from the bootlegger. The Ranger fired back with lethal aim, killing Arviso on the spot.

Within four months Holmes again engaged in a fatal gunfight near Roosevelt. On February 18, 1906, he clashed with an Apache known as Matze Ta 55 and shot the outlaw to death. In 1907 Holmes was in action again, this time trading shots with smugglers. During his years as a Ranger, Holmes never suffered a wound, and he was cited for distinguished service in the 1906 and 1907 engagements.

Arizona malefactors became wary of the sure-shooting Holmes. In 1907 a man named Baldwin murdered a Mrs. Morris and her daughter near Roosevelt. A couple of months later Holmes intercepted the murderer just outside town. Baldwin surrendered to Holmes, but the Ranger—never kindly disposed toward murderers—beat him over the head with a frying pan. Then he tied a rope around Baldwin’s neck, mounted his horse and spurred away, dragging the prisoner into Roosevelt.

In late June 1907 Ranger Frank Wheeler, by then a sergeant, rode for five days through the desert of southern Arizona Territory in pursuit of rustlers Lee Bentley and James Kerrick. Yuma County Deputy Sheriff Johnny Cameron and two Indian guides accompanied the sergeant. Saturday, June 29, was the worst day—35 miles of blazing heat through cacti and blistering sands. “Our horses went without water the entire day,” reported Wheeler, “and the water in our canteens was so hot we couldn’t even drink it.”

The next morning the guides found the outlaw camp at Sheep Dung Tanks, about three miles west of the mining settlement of Ajo. Approaching furtively on foot, Wheeler and Cameron found six horses staked out, while the two rustlers slept, rifles close by their sides. The officers readied their own rifles, and then Wheeler called out a command to surrender in the name of the law.

Both rustlers scrambled up, groping for their rifles. Wheeler and Cameron again directed them to give up, but Bentley raised his weapon and triggered a shot. For a moment the flat explosions of Winchesters broke the desert silence as each man brought his rifle into play. Kerrick, a killer and ex-convict, fired a shot at Cameron, but the deputy dropped his antagonist with the first round from his .30–30.

Wheeler emptied the five-shot magazine of his Model 1895 into Bentley. The first slug punched into Bentley’s belly, but the outlaw held his kneeling position. The Ranger pumped three more .30–40 bullets into Bentley’s torso. Yet somehow the stricken rustler stayed up, gamely trying to get his gun back into action. Wheeler’s final shot drilled into Bentley’s left temple, ripping through his head and out his right ear. Bentley fell face forward, dead when he hit the ground. Wheeler later testified that Bentley “showed more nerve under fire than he had ever seen displayed by a man before.”

Wheeler and Cameron cautiously walked over to the fallen rustlers, but both were dead. The Rangers collected several new Winchesters from the camp, threw the two bodies across a pair of stolen horses, packed everything else that needed to be hauled out and headed north. By the time they reached Ten Miles Well, a journey of 25 miles, the corpses had swollen badly in the heat. The officers sent word to Sentinel to wire for the Pima County coroner, but he refused to come. The justice of the peace at Silver Bell, who had jurisdiction over the Ajo area, also refused to come.

While waiting for Sheriff Nabor Pacheco, Wheeler and Cameron fashioned two rudimentary coffins and lowered the bodies into temporary graves. But the sheriff did not get there until Monday afternoon, and even though Pacheco brought ice, by then the bodies had decomposed beyond recognition.

Harry Wheeler, who had enlisted as a private during the Ranger expansion of 1903, soon earned promotion to sergeant, then lieutenant. In 1907 Tom Rynning was appointed superintendent of Yuma Territorial Prison, and Lieutenant Wheeler was elevated to Ranger captain. Of 107 men who served as Arizona Rangers, Wheeler was the only one who held all four ranks: private, sergeant, lieutenant and captain. He was a superlative lawman.

Harry Cornwall Wheeler was the son of a West Point graduate and colonel in the U.S. Army. Harry grew up on a series of military posts, learning to shoot on the post ranges and becoming an expert marksman with rifle and pistol. Enlisting in the U.S. Cavalry, Wheeler rose to the rank of sergeant. His last duty post was Fort Grant, Arizona Territory. Leaving the Army in 1902, he joined the Ranger company the next year. He brought to the Rangers a strong sense of duty, meticulous administrative skills, a love for fieldwork and his extraordinary gun skills—as he proved to holdup man Joe Bostwick in Tucson in October 1904.

Lieutenant Wheeler was in Benson, north of Tombstone, when he engaged in one of the great mano a mano duels in Western history. On February 28, 1907, Wheeler was made aware of a life-endangering love triangle. En route to town by train, a newly arrived couple at Benson’s Virginia Hotel had sighted the woman’s former sweetheart, J.A. Tracy. The jilted lover had pursued the couple to Benson, arriving on a night train. Presenting Lieutenant Wheeler a photograph of Tracy, the couple appealed to the Ranger for help.

Wheeler left the hotel and crossed to the depot. He found Tracy sitting on the steps of a dining car, but as the Ranger approached, the man’s former lover emerged from the hotel with her new beau. Tracy jumped up cursing and pulled a revolver from his pocket. “Hold on there!” barked Wheeler. “I arrest you. Give me that gun.”

A furious pistol duel ensued. Wheeler advanced relentlessly, firing methodically and ordering his quarry to surrender. Tracy’s third shot wounded Wheeler in the upper left thigh near the groin, but the Ranger drilled him four times, in the stomach, neck, arm and chest. Tracy tumbled onto his back. “I am all in,” he gasped. “My gun is empty.”

Wheeler dropped his Colt, having fired his five rounds (many Westerners carried only “five beans in the wheel,” leaving the hammer at rest over an empty chamber for safety). The wounded officer limped forward to secure his prisoner. But Tracy had two bullets left and more cartridges in a pocket. He treacherously opened fire again, striking Wheeler in the left heel. The fearless Ranger began hurling rocks at the downed man, whose revolver finally clicked on an empty cylinder. “I am all in,” Tracy repeated. “My gun is empty.”

But Tracy still refused to surrender his gun to Wheeler. Men in the gathering crowd threatened the gunman, but the bleeding Wheeler managed to calm onlookers and disarm Tracy. Someone brought a chair for the wounded Ranger. “Give it to him,” said Wheeler, gesturing to Tracy. “He needs it more than I do.”

Wheeler turned over Tracy to a Benson peace officer, then extended his right hand to the wounded man.

“Well,” said Wheeler, “it was a great fight while it lasted, wasn’t it, old man?”

“I’ll get you yet,” muttered Tracy with a hint of a smile. The two men shook hands.

Wheeler then retrieved his revolver and limped away to seek a physician. Authorities decided to send the grievously wounded Tracy to a hospital in Tucson and placed him on a cot in the baggage car. The train had not gone 10 miles down the tracks before he breathed his last. Wheeler later learned that J.A. Tracy had been wanted for two separate murders in Nevada, with a $500 reward on his head. One of his victims was the brother of former Ranger Dick Hickey. Nevada officials offered Wheeler the reward, but he promptly turned it down. Wheeler would have no part of blood money, instead urging that the $500 be given to the widowed Mrs. Hickey.

As a sergeant Harry Wheeler had killed Joe Bostwick, as a lieutenant he had killed J.A. Tracy, and in May 1908 as a captain he killed George Arnett. Considered by Wheeler “the worst man in Cochise County,” Arnett for months had been stealing horses in the county and driving them across the border to sell in Mexico. Acting on a tip, Wheeler enlisted Deputy Sheriff George Humm to help set a trap in a canyon east of Bisbee.

On the fifth night of their vigil, the two lawmen heard a horseman approach. The rider was leading another horse. As the rider approached within 20 feet, Wheeler and Humm each beamed a bull’s-eye lamp at the man later determined to be Arnett, ordering him to surrender.

Wheeler had leveled his revolver, and when Arnett snapped off a shot, the Ranger captain instantly triggered his .45. He heard Humm’s revolver go off beside him. The rider bolted, firing a second pistol shot before disappearing over a ridge. After retrieving their own horses, Wheeler and Humm searched the area by lamplight. Finding Arnett’s two horses, they realized the outlaw probably had been injured.

Within an hour they found Arnett’s corpse no more than a quarter of a mile from the site of the shooting. The outlaw had been hit twice. At dawn authorities brought a coroner’s jury to the rocky canyon, and an inquest was conducted that afternoon. “I have heard a relative state that Arnett had said he would never submit to arrest,” testified Wheeler. The jury exonerated Wheeler and Humm, finding it “the general opinion of the public that a dangerous man has met his end.”

In April 1908, the month before Captain Wheeler bested Arnett, Sergeant Jeff Kidder was not so fortunate in a gunfight just across the border. Wheeler had moved Ranger headquarters to the border town of Naco and ordered his men not to cross into Mexico. But when Kidder rode into Naco from his post at Nogales, Wheeler was away, and the sergeant—his Colt .45 concealed in his waistband beneath his coat—sauntered with friends into Mexican Naco.

In a cantina Kidder had trouble with a senorita. Two members of the policía hurried to the commotion, and one officer gutshot Kidder. The wounded Ranger palmed his Colt and dropped both officers with leg wounds. Kidder then staggered outside and reached the border fence a quarter mile away. Under fire he wounded the chief of police, who was the brother of the officer who shot Kidder. Once out of ammunition, the Ranger surrendered.

The chief and his men dragged Kidder to jail, where they robbed him and roughed him up. Although permitted visitors from the American side, including physicians, he died 30 hours after being shot. Jeff Kidder was 33.

That summer Ranger Billy Speed had a confrontation with hard-driving ex-convict William F. Downing, a terror in Willcox, Arizona Territory, where Speed was stationed. Downing, who toted a revolver in his hip pocket, ran the Free and Easy Saloon and clashed openly with many local men. Although threatened repeatedly by Downing, Speed was not intimidated, and he remained mindful of Wheeler’s admonition that “if anyone must be hurt, I do not want it to be the Ranger.” Kidder’s recent death was on Wheeler’s mind, and he wrote Speed “to take no chance with this man in any official dealing you may have with him.” Wheeler left no doubt as to his meaning: “I hereby direct you to prepare yourself to meet this man…and upon his least or slightest attempt to do you harm, I want you to kill him.”

On the night of August 4 Downing hit and then gouged the eyes of saloon girl Cuco Leal, who lived and worked in the Free and Easy. She swore out a warrant, and Constable Bud Snow—a former Ranger—sought Billy Speed’s help. Speed advised they wait until morning. Early on the 5th the still drunk Downing emerged from his saloon shouting crude threats against Speed and Snow. The lawmen armed themselves and split up to corral Downing.

As Speed turned down an alley, a bystander shouted that Downing was coming up the street. Winchester at his shoulder, the Ranger emerged and ordered Downing to throw up his hands. The saloonkeeper raised his arms and walked unsteadily toward Speed. When he was less than 30 feet from the Ranger, Downing suddenly groped with his left hand at his hip pocket, apparently forgetting he had left his revolver at the Free and Easy. Still he kept advancing, and Speed again shouted for him to throw up his arms.

Left with little choice, Speed finally squeezed the trigger of his Model 1895 Winchester. The .30–40 slug ripped into Downing’s right breast, exiting beneath his right shoulder blade. The impact threw him onto his back, and within minutes he was dead. Captain Wheeler took the first train to Willcox, where a coroner’s jury had ruled Ranger Speed “perfectly justified” in killing Downing. Wheeler reported to Governor Joseph H. Kibbey, “This is the first time I have ever known a killing to meet absolute general rejoiceing [sic].”

The deaths of Downing and Arnett in 1908 left no other prominent badmen in Arizona Territory. The Rangers had relentlessly hounded most other criminals. For instance, during the fiscal year of 1904–05 they made 1,052 arrests. But by late 1908 the company had virtually achieved its goal of cleaning up the territory.

Harry Wheeler’s report for the month of August 1908 revealed the Rangers had made fewer than two-dozen arrests. He reported, “The whole country seems remarkably quiet, and scarcely any crimes are being committed anywhere.” With obvious disappointment, he added, “There has been absolutely no trouble of any kind, and I am getting tired of so much goodness, as are all the men.”

The Rangers had worked themselves out of a job. Several Arizona sheriffs complained about the authority Rangers exercised within their jurisdictions. Many Democrats, resentful that the Ranger company was a creation of Republicans, clamored that to continue it would be a waste of funds. In February 1909 the Democrat-controlled Territorial Legislature abruptly disbanded the company—with Rangers still in the field. Wheeler had not been permitted to testify on behalf of his beloved Rangers.

From late 1901 until early 1909 the hard-riding, quick-triggered band of riders had brought into a new century the crime-fighting traditions of Wild Bill Hickok, Pat Garrett, Commodore Perry Owens and other members of an earlier generation of frontier lawmen. The gunfights presented here were the ones with fatal consequences, but there were many other shooting incidents involving Rangers. While there was occasional gunplay during Arizona’s early statehood period, the Rangers had claimed the last sustained gunfighting adventure of the no-longer-so-Wild West.

Texas State Historian Bill O’Neal is an award-winning author of many books and magazine articles about the Old West. For further reading see two of his books: The Arizona Rangers (1987) and Captain Harry Wheeler, Arizona Lawman (2003).

Featured Article

Lawmen’s Heated Gun Battle in Hot Springs

When it comes to naming the wildest towns in the Wild West, the mining town of Tombstone, Arizona Territory, looms near the top on most anyone’s list. Tombstone, when it was booming in the early 1880s, featured gambling, shootings, political factions that divided the law enforcement community and, of course, the gunfight near the O.K. Corral, in which three Earp brothers and Doc Holliday killed three uncooperative cowboys. On the other hand, the resort town of Hot Springs, Arkansas, which got its name from the geothermal springs in the area, probably would not even make such a ‘wildest’ list. Yet one could find a hot time in that old town, too. Hot Springs had gambling galore, its share of shootings, law enforcers who definitely did not see eye to eye and two shocking gunfights on the same day–the first resulting in no casualties, but the second leaving five men dead.

The Arkansas shootout that had a higher body count than the famous 1881 Tombstone fight occurred on March 16, 1899, and pitted lawmen against lawmen–the Garland County Sheriff’s Office vs. the Hot Springs Police Department. News of the Shootout on Central Avenue made the papers from New York City to California (though it became old news fast) and left the city fathers distressed. After the gunfight, lines of visitors rushed to take the next train out of town. Hot Springs depended on the tourist trade for its economic health, and a battle between local badge-wearers in the middle of Central Avenue was not exactly good for business.

Hot Springs, some 52 miles southwest of Little Rock, was a site well known to American Indians. The little village that sprang up around the springs in the late 1820s was known as Thermopolis, but its first real resort season was the summer of 1832. That year, U.S. President Andrew Jackson signed a special act of Congress to protect what became known as Hot Springs. Stage service from Little Rock began three years later, and in 1851 Hot Springs was incorporated as a town. The place became virtually deserted during the Civil War but experienced a postwar population boom as more and more visitors ventured there to bathe in–and also drink–the legendary waters. By the mid-1870s, the federal government had begun administration of the Hot Springs Reservation (which would be renamed Hot Springs National Park in 1921).

On January 15, 1874, an undetermined amount of money was taken when a stagecoach was robbed five miles east of Hot Springs on the road to Malvern, Ark. The robbery has been pinned on the famous James-Younger Gang, though some historians say otherwise. About eight months later, another stage robbery occurred about 10 miles east of Hot Springs, with the thieves taking some $1,000.

The same year, successful businessman Joseph ‘Diamond Jo’ Reynolds decided to take a stage from the train station at Malvern to Hot Springs, where the soothing waters would help his rheumatism. That particular stage was not held up, but the terribly bumpy ride is said to have inspired Diamond Jo to build a 22-mile connecting narrow-gauge railroad between Malvern and Hot Springs. With this more comfortable transportation, Hot Springs became one of the favorite destinations not only of one-time New Yorker Reynolds but also of many other wealthy people from across the nation. Some of these visitors wanted more than just hot thermal baths. The local people were swift to comply, and watering holes sprang up to the point where one visitor wrote home, ‘I believe there is a saloon in every other store.’ Also springing up were brothels and gaming establishments. By the late 1870s, gambling, which probably existed in Hot Springs as early as 1849, had become a local growth industry that rivaled the healing waters. The question of who would control the gambling became an issue that influenced every election for many years.

In February 1884, a gunfight occurred on Central Avenue between two gambling factions, known as the Flynns and the Dorans. Frank ‘Boss Gambler’ Flynn’s control of most of the gambling houses on Central Avenue had been challenged by Major S.A. Doran, a Confederate veteran who refused to submit to Flynn’s bullying. Each man had hired gunmen to protect his interests. Flynn’s plans to ambush Major Doran didn’t work out, but Doran’s gunmen soon went to work, opening fire on Flynn and his two brothers as they rode in a horse-drawn cab along Bath House Row. In the ambush and ensuing gun battle, three men were killed and three others, including Frank Flynn, were wounded. Within a few hours, a vigilante group called the Committee of Thirteen had formed, and these vigilantes herded many gamblers at bayonet point to the trains for hasty departures.

Gambling in the spa city had taken a hit, but before long it revived and came on stronger than ever. The ‘Liberals’ knew that gambling was good for business, so they strived to make Hot Springs a wide-open town again. ‘Conservatives,’ who thought that refreshing waters were enough to soothe a man’s soul, fought to suppress gambling and keep Hot Springs healthier and safer for citizens and visitors alike. The position of mayor was hotly contested every two years. The elected mayor got to pick his chief of police, who held a lot of power there in the 1880s and ’90s. Gambling and prostitution either thrived or dried up depending on the politics of the mayor and police chief.

In the election for mayor in 1897, Independent candidate William L. Gordon defeated Liberal incumbent W.W. Waters. Thomas C. Toler, who had been the chief of police at the time of the Flynn-Doran gambling battle, helped Gordon get elected, so Gordon appointed him to the chief’s job again. Toler was actually a Liberal with connections in the gambling community. Unlike Mayor Gordon, Toler liked Hot Springs better when it was an open town. The two men soon argued about policies, and Gordon tried to dismiss the popular Toler. The city council members sided with the chief, so Gordon backed off.

With another election coming up in April 1899, Toler suddenly threw his support to Independent candidate C.W. Fry. Fry announced that if elected he would reappoint Tom Toler as chief of police. Trouble began to brew in a town that now had some paved streets, as well as electric trolleys, or streetcars, moving hundreds of visitors every day. The Democratic mayoral candidate, young businessman George Belding, had the support of perhaps the most powerful man in Garland County, Sheriff Robert L. Williams. Belding assured Williams that if elected mayor he would make Chief Deputy Sheriff Coffee Williams, the sheriff’s brother, chief of police. Such a development would mean control of the entire county for the Williams brothers. Until the 1899 election caused them to bump heads, Toler and Bob Williams had been warm friends.

Toler, 45, was an experienced lawman, having been hired as a deputy in the early 1870s by the first sheriff of Garland County, William Little, and then appointed chief of police in 1883. During the Flynn-Doran fight the following February, he had disarmed the combatants and herded some of them off to jail. Afterward, one of the gunmen brought in by Major Doran, Edward Howell, hung around town threatening to kill Chief Toler on sight. Toler headed over to Howell’s favorite drinking establishment, the Opera House Saloon, and shot the gunman dead. It was ruled self-defense.

Another time, Toler got the best of a Hot Springs encounter with O.K. Corral participant Wyatt Earp, at least according to the March 17, 1899, edition of the Arkansas Democrat: ‘A dozen or more years ago, [Toler] made Wyatt Earp, a notorious western killer, walk out of Hot Springs.’ Earp, the newspaper reported, was having a run of bad luck and getting mad about it. Chief Toler arrived and took Earp aside, telling him that Hot Springs welcomed visitors but didn’t want troublemakers. Earp didn’t press the issue, but the following night Toler was again summoned because Wyatt was drinking, losing and acting surly once more. At that point, Toler informed Earp he was ‘posted’ out of town, and Wyatt departed Hot Springs without further incident.

Toler, who lived with a woman referred to as Mrs. Toler in official records, was the kind of police chief the citizens of Hot Springs wanted. He and his 10-man department collected enough fines to pay the salaries of the force, but they enforced the law without any undue hardship on the tourist trade.

Toler’s second-in-command, Captain Lee Haley, was a painter by trade, but he had ventured into law enforcement and come to like it. Haley, 33, had married a local girl, and they had two children. Sergeant Thomas F. Goslee, a printer by trade, was considered a top-notch officer, fearless and totally loyal to Toler. Haley, Goslee and Toler would all be involved in the March 16 fight with members of the sheriff’s office, as would detective James E. Hart. Known by many Hot Springs residents as ‘Uncle Jim,’ the English-born Hart was in his 40s but looked considerably older. Appointed chief of police by Mayor D. Kimbell in 1887, Hart had proved too straight-laced for everyone and had accepted a demotion to remain with the department. He had a wife who was blind and three children.

The Hot Springs Police Department was supportive of its chief but no more so than the Garland County Sheriff’s Office was supportive of its sheriff, Bob Williams. Born in Kentucky on January 22, 1851, Bob had moved with his family to Texas during the Civil War. After the war, the Williams family tried farming in Arkansas’ Polk County. Bob married Martha Allen there in 1872, and the couple moved to Hot Springs in 1878. Once he had found financial success as the owner of a mercantile store, his parents joined him in Hot Springs, as did his older sister, Matilda Watt, and her family and his younger brother, J.C. Williams, who everyone called ‘Coffee.’ Bob Williams entered the sheriff’s race in 1886 and won as a Democrat. He was re-elected in 1888 and 1890 and then was voted in as mayor in 1893. He chose not to seek a second term. When he decided he wanted to be sheriff again in 1898, he ran successfully as an Independent.

Bob Williams was an outgoing individual, polite to women and friendly to most men, except those who disagreed with him too much. His brother Coffee had greater flaws. He drank too much and spent too much time hanging around the gambling clubs. Several of his business ventures had not worked out, and Bob had had to bail him out a few times. But Bob had appointed his brother chief deputy sheriff, and Coffee had handled his duties well. Bob Williams also appointed two nephews, Sam and Will Watt, as deputies. Sam showed good judgment and composure on the job, but Will was a bit unstable and more impetuous. The sheriff’s 22-year-old son, Johnny O. Williams, was managing the mercantile store in March 1899, but he had ridden on several posses headed by his father, and he loved to go out and practice target shooting with Uncle Coffee. Bob Williams’ friend Dave Young was a part-time deputy sheriff who occasionally worked in a liquor store. Last but not least of the deputies was Ed Spear, a tall, prematurely balding man who had been in his share of trouble but was now a loyal and supportive deputy, very much in Sheriff Bob Williams’ inner circle.

On the morning of March 16, 1899, a caucus of Independent Party leaders met in the City Hall office of Police Chief Toler. Mayoral candidate C.W. Fry was present, along with a dozen or more other people, including several police officers. What was said at the meeting is not known, but it stands to reason that the officers were told that if Fry was elected, then Toler would be reappointed police chief and all the policemen would be able to keep their jobs. As soon as the meeting concluded, an unidentified man phoned Bob Williams at the courthouse, telling him all about it. The angry sheriff then stormed downtown. When he arrived on Central Avenue at about 1:30 p.m., he spotted his pal Dave Young. Over lunch at the Klondike Saloon, Williams complained to Young about the disturbing meeting at City Hall. At about that time, Sergeant Tom Goslee of the Hot Springs Police Department was having a piece of pie at Corrinne Remington’s cafe. Afterward, he went to Tobe and York’s barbershop at 614 Central for a quick haircut. Goslee had left his .44-caliber service revolver in his desk, but he carried a two-shot derringer.

Williams and Young finished their meal and walked north on Central to the corner of Spring Street, where they stopped to talk some more in front of Joseph Mazzi’s saloon. Seeing Goslee come out of the barber shop across the street, the sheriff called out to him. Goslee waited for a trolley car to pass, then crossed over to the two unsmiling men. Instead of shaking Goslee’s hand, Williams gave the sergeant a piece of paper. ‘These are the people who held a caucus in the chief of police’s office this morning against Belding,’ the sheriff said. Goslee could see his own name on the list. ‘And I want to know what you mean by working against me,’ Williams demanded. Goslee calmly replied, ‘I am not unfriendly to Belding and have taken no active part in the caucus you have referred to.’ But then he saw fit to defend Police Chief Toler and even accuse Williams of being Toler’s enemy. The sheriff called Goslee ‘a liar and a coward’ and began a long tirade. When Williams seemed to move his hand toward his coat, Goslee responded by drawing his derringer. ‘I want no trouble from you, as you are the sheriff of the county,’ the sergeant said, ‘but I will defend myself if forced to.’

Dave Young stepped between the two men, gently placing a hand on each man’s shoulder. ‘Boys, boys, this will not do,’ he said. Later, he would tell an acquaintance, ‘I believe that Goslee would have killed Bob Williams had I not stepped between the two.’ As it was, the sheriff opened his coat and said, ‘As you can see, I am not armed,’ but he continued fuming at Goslee. Then the sheriff saw his son Johnny come out of the City Hall Saloon, at the intersection of Central and Prospect, and broke away to greet him. According to witnesses, Johnny Williams handed his father a short-barrel .44 revolver and then called to a friend, who passed him another revolver.

Someone shouted ‘Look out!’ and gunfire quickly followed. Witnesses were divided over who fired the first shot, but Goslee would have been a fool to start a street gunfight armed with only a two-shot derringer. In any case, the sergeant had soon emptied both barrels and was retreating under fire. One bullet barely missed his head and embedded in the doorframe of Justice W.A. Kirk’s office. Other bullets ricocheted against the brick wall of F.J. Mobb’s drugstore. Bob and Johnny Williams kept shooting until their guns were empty, but they couldn’t get their man. Goslee slipped down an alley and stumbled into the lobby of the Sumpter House, not wounded but badly shaken. Goslee remained in the little hotel until Chief Toler and another officer arrived to escort him to City Hall.

Toler notified David Cloud, Garland County prosecuting attorney, who quickly took statements from Sergeant Goslee and Sheriff Williams. Each blamed the other. Cloud believed Goslee and issued a warrant for Bob Williams’ arrest. The sheriff made bail, but the charge against him did nothing to improve his mood. Even though 14 shots had been fired, nobody had been hurt in the gunfight. Credit poor marksmanship or dumb luck. But the trouble wasn’t over, not by a long shot. Less than three hours later, their marksmanship would improve or their luck would run out–two of them would be dead and the third indicted for murder.

The city fathers were not happy that a gunfight had taken place on Hot Springs’ main street, and Toler called Goslee into his office and said that the volatile situation had to be defused before further trouble occurred. He suggested that the sergeant meet with Johnny Williams, shake his hand and maybe have a drink, while he himself would try to patch things up with Sheriff Bob Williams. Toler then called for a meeting in his home, not wanting to risk another leak from the ‘City Hall spy.’ In attendance were C.W. Fry, Sergeant Goslee, Captain Haley, Arlington Hotel owner Samuel H. Stitt, and large-property owner George M. French. The chief went over the events of the day, and they discussed their plans on how to lessen the tension between the two law enforcement departments.

When Toler called Bob Williams at his office and asked to meet for drinks at 5:30 p.m., William reluctantly agreed but said it had to be a short meeting because his daughter Florence was celebrating her 21st birthday that night. Williams then contacted his brother, Chief Deputy Sheriff Coffee Williams, at the Arkansaw Club, an elaborate gambling and sporting palace, and told him to get back to the sheriff’s office. After that, the sheriff heard from his son Johnny, who said that Goslee had called him to set up a friendly meeting. Bob Williams was suspicious. When Coffee arrived, the sheriff told him to accompany Johnny to the meeting. Coffee went to his desk and took out a revolver, which he stuck in the back of his waistband. Next, the chief deputy sheriff put on a brown suit coat, long enough to hide the gun. Coffee then walked with nephew Johnny on the east side of Central Avenue, heading north. They were soon joined by Deputy Ed Spear, and the three men stopped to talk. Back at the courthouse, Bob Williams briefed nephews Sam and Will Watt on what was going on and strapped on an old Colt revolver. They then headed outside toward Central Avenue. Before long, Dave Young joined them.

After the small meeting at Toler’s house ended, the chief of police, Captain Haley and Sergeant Goslee walked south on Central Avenue. Shortly after passing Oliver and Finney’s grocery store at 607 Central, they spotted Coffee Williams, Johnny Williams and Ed Spear walking north on the same side of the street. As the two groups neared each other, Johnny Williams stepped up and extended his hand to Goslee. The sergeant shook hands and said, ‘Johnny, I am an officer and can’t be shooting around on the streets.’ Young Williams smiled and said, ‘All right, Tom, I want everybody for my friend.’

Seeing how well things were going, Chief Toler and Captain Haley moved down the sidewalk to Lemp’s Beer Depot, where Haley’s brother-in-law, Louis Hinkle, was a bartender. Lemp’s folding doors were open wide so that customers could stand at the bar and still enjoy the fresh air. Haley leaned against one end of the bar to talk to Hinkle. Chief Deputy Sheriff Coffee Williams and Deputy Spear had also drifted up the sidewalk and were now only a few feet away from Haley.

Seeing Spear standing there, Haley addressed him, ‘Ed, I understand you have told people that if I put my head out, you’ll shoot it off.’ The accusation appeared to stun Spear for a moment. Then the deputy said, ‘Haley, anybody who said I told that is a goddamn liar.’ Hinkle took offense at Spear’s denial. ‘Don’t you make me out a liar,’ he snarled. Hinkle then put one of his powerful arms around Spear’s neck and tilted his head upward. In his other arm, the brawny bartender held an Anheuser-Busch knife with a 6-inch blade. It was no bluff. In one motion, Hinkle slashed Spear’s throat.

With his throat bleeding profusely, Spear struggled to free himself. Hinkle wasn’t ready to let go. ‘Stop, for God’s sake,’ Haley pleaded. Chief Toler and Sergeant Goslee both started toward the struggling men, intending to break them apart. Before they got there, Spear twisted partially free, just enough so that he could yank out his .45-caliber revolver and pull the trigger. The bullet hit Hinkle in the throat and exited below his ear. The bartender released Spear and staggered backward. Coffee Williams took the opportunity to pull out his revolver and shoot Hinkle in the chest.

Meanwhile there was more shooting going on. While running on the sidewalk toward the fray, Goslee went down. Johnny Williams had shot him twice, one bullet striking the sergeant just below the right knee and the other hitting him in the right groin, severing the femoral artery. The sergeant struggled up onto his left elbow and fired back at Johnny Williams, who was some 35 or 40 feet away. The shot struck the sheriff’s son in the head. Young Williams crumpled to the sidewalk near the entrance to the Klondike Saloon. He was mortally wounded, but Goslee wouldn’t make it either. A shot from Coffee Williams finished off the sergeant.

Tom Toler quickly got into the act, firing at Coffee Williams, who backed into the street and took refuge behind a parked express wagon. Coffee fired back at the chief of police from behind the wagon, but Toler’s attention was soon diverted by a shot fired at him by the game Ed Spear, who was not letting his throat wound knock him out of the fight. Toler sent a couple of bullets Spear’s way, one of which grazed Spear’s right shoulder. With Spear and Coffee Williams shooting at him from both sides and the merchants’ doors all locked behind him, Toler felt trapped. He ran north on the sidewalk, trying to get a clear shot at Coffee, but the deputy chief moved from the back of the express wagon to the front and began firing his two six-shooters over the seat. Two bullets struck Toler at virtually the same time–the one that got him in the back of the head probably delivered by Coffee Williams, the one that got him in the chest probably unleashed by Spear. Either shot would have been fatal.

But what of Captain Haley, whose comment to Spear seemingly opened the door for all the violence that followed? Witnesses later reported that when the first shot was fired by Spear, Haley had stood stunned for a few seconds and then had turned and run across Central Avenue, eventually finding refuge in Tobe and York’s barbershop. ‘A shot was fired and blood flew in my face and eyes and I retreated into the street blinded,’ Haley later testified. Strangely, neither Spear nor Coffee Williams had appeared concerned that the police captain was behind them on the west side of the street. Indeed, Haley never returned to the conflict. He had fled, much as Ike Clanton had done during the October 1881 Tombstone fight.

After Toler went down, the shooting stopped. Hinkle and Goslee were already dead, Johnny Williams was dying on the sidewalk, and Haley was in hiding. Spear managed to stumble into the Klondike Saloon. ‘Boys, I am badly wounded,’ he gasped. ‘For God’s sake send for a doctor to help me.’

He then collapsed on the saloon floor, but, amazingly enough, it would not be his last gasp or last collapse. Coffee Williams stepped out from behind the express wagon and found himself standing alone in the street. He rushed over to his nephew, Johnny Williams, and called out for a doctor. But Coffee wasn’t sure it was really safe on the street. Still clutching his two six-shooters, he backed through the doorway of the Klondike.

Citizens were slow in opening their doors and coming out to check on the damage. Only a few brave souls had done so by the time Sheriff Bob Williams arrived on the scene with deputies Sam and Will Watt and part-time deputy Dave Young. The sheriff first saw the bodies of Hinkle, Goslee and Toler, but his first cry of anguish didn’t come until he recognized that the fourth fallen man was his son, Johnny. Turning to his brother, the sheriff said: ‘My God, Coffee, did you do this? Is Johnny dead?’ Coffee was ready with an answer: ‘Yes, Johnny is dead, and I killed the son-of-a-bitch who killed him.’ At that point, the sheriff probably figured that the police had tried to ambush his men, not knowing that it was a spur-of-the-moment knifing by bartender Hinkle that had led to all the rest. Will Joyce, a friend of the sheriff’s, later testified that he saw Bob Williams cursing and stalking up and down with a revolver in each hand. Joyce helped carry Johnny into the Klondike Saloon while the young man’s father continued to rage. Resident C.H. Weaver, who had considered running for mayor, tried to calm the sheriff, but Bob Williams stuck both revolvers in Weaver’s face and cursed him. Weaver walked away, badly shaken but unharmed.

Detective Jim Hart would not be so lucky. He had been over at the Diamond Jo Railroad Depot trying to keep riffraff and con men out of town when someone rode up to him and announced that there was ‘big trouble over on Central Avenue.’ Hart hurried to the shocking scene, where he didn’t even bother taking his revolver out, according to the later testimony of four people, including Mrs. Toler. That didn’t mean anything to Bob Williams. The sheriff walked up to Hart, grabbed the lapel of his coat with his left hand and said, ‘Here is another of those sons-of-bitches!’ Cocking the revolver in his right hand, Williams fired point-blank into Hart’s face. The hapless detective fell, his face blackened from the muzzle blast and his scalp blown off. That did not stop Deputy Will Watt from reaching over the shoulder of his uncle-sheriff and firing two more bullets into Hart. People who had come out of stores and homes fled back inside again. But not Mrs. Toler, who stood with her hands on her hips, staring directly at Bob Williams. She later said that the sheriff told her, ‘Yes, we got Toler, and I wish we had you where we’ve got him.’ After he said it, she went home without a word-not to weep but to get a loaded gun that her late husband kept in a bureau drawer. She wrapped the gun in her shawl and went back to Central Avenue, intent on ‘killing Bob Williams,’ but by then the sheriff was gone.

Johnny Williams had not yet died, so Bob Williams had ordered some men to take his son home. The little birthday party for the sheriff’s daughter, Florence, was off. Instead the Williamses made Johnny as comfortable as possible and stayed with him until he died at 9:30 that night. Back on Central Avenue, the other fallen men lay unattended. Members of the sheriff’s office were still acting as if the conflict would resume. Dave Young, who had been unarmed and had not taken part in the street fight, borrowed a doublebarreled shotgun from one of the saloons. Coffee Williams, who had emptied two revolvers in the fight, tried to get more ammunition from Babcock’s hardware store. ‘They would not give me any,’ he said later. Nephew Will Watt then found him some cartridges. These preparations were not necessary, however. The Hot Springs Police Department had been defeated, and the carnage was over. Amazingly, though five men had been shot down in the Shootout on Central Avenue, the only bystander wounded was a young man named Alan Carter, who took a stray bullet while watching the action.

Storeowners called City Hall to complain about the dead bodies on the sidewalk. Finally, Constable Sam Tate and his deputy, Jack Archer, brought the bodies of Hinkle, Goslee, Toler and Hart by freight wagon to the Gross Funeral Home. Tate stood in the rear of the wagon, with arms crossed and displaying two drawn revolvers.

Mayor W.L. Gordon called an emergency meeting at City Hall and appointed L.D. Beldin to replace the fallen Tom Toler as chief of police. Next, Gordon and Beldin selected 150 men to carry out armed patrols to prevent any unlawful acts. They could not, however, stop visitors from departing town in droves. ‘The tragedy at Hot Springs resulting in the killing of five men and the probable fatal wounding of a sixth is one of the most deplorable affairs of this kind that has ever occurred in the state of Arkansas,’ the Arkansas Gazette stated. The Arkansas Democrat compared the street fight to those that had occurred earlier on the Western frontier: ‘That was a terrible affair at Hot Springs. Five men killed and another wounded in a street duel is a record seldom attained by the wild, reckless elements in new western towns. It is needless to say the whole state was shocked by the news of the tragedy.’

Hearings were held at City Hall the next day. Governor Dan Jones attended at the request of a number of businessmen. Coroner E.A. Shippey presided over the inquest. The jury quickly concluded that Sam Watt and Dave Young had not taken an active part in the gunplay. R.L. (‘Bob’) Williams, Coffee Williams, Will Watt and the wounded Ed Spear were charged with ‘unjustifiable homicide’ and were remanded to the county jail. All made bail.

A series of courtroom trials began, but all came to naught. Spear claimed that he acted in self-defense after Hinkle attacked him with a knife. Coffee Williams claimed that he had shot Hinkle to help a fellow deputy in need, and that he had fired at Goslee and Toler only because they were shooting at him. The trials of Sheriff Williams and Will Watt ended in hung juries. Although several witnesses testified that Williams and Watt had shot down detective Hart, several other people came forth to say that Hart had first drawn his gun on Williams. Neither the sheriff nor his brother nor his nephew nor Ed Spear would have to serve a single day in prison. Hart’s blind widow later filed a civil suit for $20,000 against Sheriff Williams, but Will Watt testified that he had killed Hart to save his uncle’s life, and the jury found for the defendant. Understandably, Hot Springs would take some time to recover from its Tombstonelike gunfight. For one thing, the relations between the Garland County Sheriff’s Office and the Hot Springs Police Department remained strained well into the 20th century.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!

Articles 2

Articles 3

Articles 4

Articles 5

Articles 6