In December 1941, someone leaked America’s top-secret blueprint for war for all the world—even Hitler—to see

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]hicago Tribune reporter Chesly Manly knew the document in front of him was the scoop of a lifetime. The date was December 2, 1941, and Manly was reading the U.S. War Department’s most closely guarded secret, a detailed plan to defeat Germany and the Axis in a war that the United States had not yet entered and that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had vowed to keep the country out of.

Manly studied the 350-page tome and wrote his story the next day. Though the plan was a military secret, Manly believed the public was entitled to know about it, and he got the go-ahead from Tribune publisher Robert R. McCormick, a strident isolationist and ardent foe of all things Roosevelt.

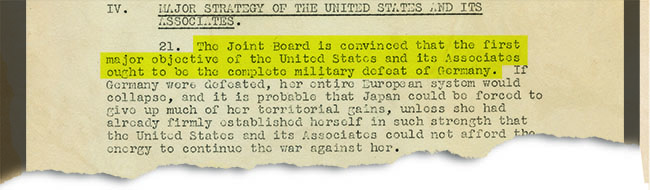

“F.D.R.’s War Plans!,” screamed the front-page banner headline in the Tribune’s Thursday, December 4 edition. Smaller headlines proclaimed, “Goal Is 10 Million Armed Men” and “Proposes Land Drive by July 1, 1943, to Smash Nazis.” The Tribune’s sister paper, the Washington Times-Herald, played the story big, too.

The secret military plan was a “blueprint for total war on a scale unprecedented in at least two oceans and three continents, Europe, Africa, and Asia,” Manly wrote, and he reported that July 1, 1943, was the date fixed for an Allied invasion of Europe. The plan called for a U.S. armed force of 10 million men, more than seven times the strength at the time, with five million slated to be deployed to Europe. The War Department admitted that Britain and Russia alone could not beat Hitler, Manly noted, and that victory would require the United States to enter the war. An ecstatic McCormick congratulated Manly and the rest of the Tribune’s Washington bureau on what he called “perhaps the greatest scoop in the history of journalism.”

The story was a complete surprise to the government and hit official Washington like a bomb. “Nothing more unpatriotic or damaging to our plans for defense could very well be conceived of,” Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson confided in his diary. While never denying the story’s accuracy, angry government officials vowed to track down whoever had leaked the plan to Manly. The FBI interviewed hundreds of people—but no one was ever charged and the mystery remains unsolved to this day, at least officially. Still, there are clues, some only revealed decades later, that show how the details of a top-secret war plan ended up on the front page of the Chicago Tribune just three days before the Pearl Harbor attack.

DURING THE PREVIOUS YEAR, Roosevelt had edged the United States closer to war. A peacetime draft expanded the army to 1.4 million men, up from 190,000 in 1939. Under the March 1941 Lend-Lease Act, American industry was supplying planes and munitions to Britain and the Soviet Union. Most Americans, however, wanted no part of the war. A February 1941 Gallup poll showed that 78 percent opposed entering it. The America First Committee—a politically powerful isolationist group claiming more than 800,000 members—spoke for this majority and supported a potent like-minded bloc in Congress.

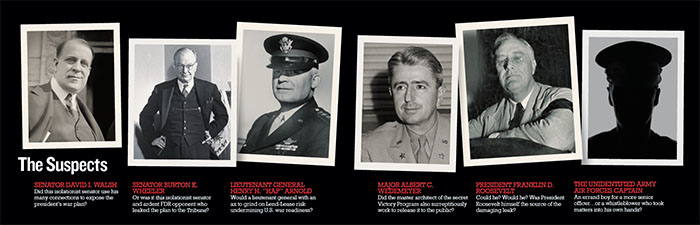

“Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars,” Roosevelt had assured voters during the 1940 presidential campaign. But his opponents labeled him a liar: isolationist senator Burton K. Wheeler, a Montana Democrat, called the president a “war-minded” man whose foreign policy “will plow under every fourth American boy,” while famed aviator Charles A. Lindbergh, who gave America First its star power, claimed the country was being lured “to share with England militarily, as well as financially, the fiasco of this war.”

A dissident of a different stripe was Lieutenant General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, 55, chief of the U.S. Army Air Forces. He objected to sharing secret technology with Allied nations, prompting Roosevelt to threaten to exile him to Guam. Arnold’s main gripe was that Lend-Lease was siphoning off modern planes the air force desperately needed for national defense.

But while the arsenal of democracy was gearing up for war, millions of dollars were being spent with no clear idea of what it would take to beat Germany and Japan. On July 9, 1941, Roosevelt secretly ordered the army and navy to determine the “overall production requirements required to defeat our potential enemies.” The army assigned the main portion of this project to Major Albert C. Wedemeyer of the War Plans Division.

Wedemeyer, 44, was a curious choice. He was a vocal isolationist, colleagues later said, one of them adding he was “most pro-German in his feelings, his utterances, and his sympathies.” A friend of both Lindbergh and Senator Wheeler, he had even attended an America First rally.

Still, Wedemeyer gave it his all, planning for a war he did not want. He toiled for long hours in the hot, cramped Munitions Building in Washington, DC, devising what he later called a “plan calculated to bring our enemies to their knees in the shortest possible time.” His most shocking conclusion was that preparations would take nearly two years—until July 1, 1943—before “US armed forces can be mobilized, trained, and equipped for extensive operations.”

On September 11, 1941, U.S. Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall and Chief of Naval Operations Harold R. Stark approved the plan, known as the Victory Program. Thirty-five mimeographed copies were made, all given to military officers.

On December 4, 1941, the day Manly’s story appeared in print, shocked officers stood in small groups inside the War Department, talking in hushed tones. “Look at this!,” exclaimed Brigadier General Leonard T. Gerow, head of the War Plans Division, as he showed the story to colleagues. Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy confronted Wedemeyer, telling him, “There’s blood on the fingers of the man who leaked this information.” Major Laurence S. Kuter, who had helped draft the air force portion of the plan, told a Tribune reporter, “There are people here who would have put their bodies between you and that document.”

Military contingency plans for time of war are far from uncommon. Indeed, Roosevelt’s War Department had many, even a plan—War Plan Red—for hostilities with Britain. But the Victory Program was different. With its declaration that the United States must enter the war to save Britain, its target date for the beginning of offensive operations, and its specificity in the number of men and amount of materiel needed to defeat Germany, it was a blueprint for expected American involvement in the ongoing war in Europe.

The article embarrassed the White House, showing that Roosevelt was plotting for war while promising peace, but the administration’s initial response was lackluster. Secretary of War Stimson was absent, undergoing dental work in New York that day, while Roosevelt’s press secretary, Stephen T. Early, refused to either confirm, deny, or condemn the story. That night, however, Stimson found the president “full of fight,” and they agreed that Stimson would give a stronger response the next day.

On December 5, 1941, Stimson met with a roomful of reporters. Speaking with “uncommon vigor,” the New York Times noted, he accused the Tribune and its publisher of being “so lacking in appreciation of the danger that confronts the country and so wanting in loyalty and patriotism to their government that they would be willing to take and publish such papers.” Privately, he saw the uproar as a chance “to get rid of this infernal disloyalty which we now have working in America First and in these McCormick family papers.”

At a cabinet meeting that day, Attorney General Francis B. Biddle suggested Manly’s story may have violated the 1917 Espionage Act by making secret military information available to potential enemies. Stimson and Interior Secretary Harold Ickes both wanted Manly and McCormick arrested. A still-angry Roosevelt ordered the FBI and the army to investigate.

While the administration directed its ire at the Tribune, the more crucial question was who had given Manly access to the top-secret document. Investigators quickly realized the reporter had seen an actual copy of the Victory Program because, they assessed, he could not have written “such a complete, concise and accurate report of the plan unless the entire data were available.” The War Plans Division found all 35 copies where they were supposed to be, but lax security eliminated any paper trail. At least 109 army officers and a like number of naval officers had legitimate access to the plan. The number of people who could have swiped the document and returned it without detection was, the FBI concluded, “legion.”

INVESTIGATORS INSPECTED the leak came from an isolationist intent on showing Roosevelt’s alleged duplicity, and they soon found the War Department was rife with men hostile to the president’s foreign policy. An ambitious officer trying to embarrass his boss became another possibility once the FBI discovered a clique of high-ranking officers who believed their superiors were “boneheads” and that victory would be won “only when the top-ranking officers are replaced with more capable men.”

Because of his familiarity with the plan and his known isolationist views, Wedemeyer was the prime suspect, but he adamantly denied leaking the plan. FBI agents examined Wedemeyer’s copy and found the parts Manly quoted had been underlined, as if Wedemeyer had highlighted them for the reporter. Wedemeyer, however, claimed he had underlined these sections when he read the story to determine how much of the plan had been compromised. Agents suspected bribery when they found a recent large deposit in Wedemeyer’s bank account, but he was able to prove that the money was an inheritance. The FBI never found any direct evidence tying Wedemeyer to the leak. The army, however, remained suspicious. Military investigators found him “very ill at ease” and continually “thinking up excuses for himself and his actions.”

On December 7, 1941, the question of American involvement in the war was settled when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The United States declared war on Japan the next day; three days after that, Germany declared war on the United States. But the investigation continued.

FBI Agent Joseph A. Genau and two army officers questioned Manly. A 36-year-old Texan whom an acquaintance called “the picture of courtesy and grace,” Manly was a veteran newsman, having worked for the Tribune since 1929. He politely but firmly refused to name his source.

Army investigators pressed him. They needed to know who had leaked the plan, the investigators said, to keep “innocent heads from rolling in this thing”—heads belonging to “some mighty fine officers who have spent a lifetime in the War Department and who are going to take the rap.” They even falsely claimed that “many people in important places” believed Manly’s story had prompted the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Manly stood his ground.

Other Tribune officials were no more helpful. Washington bureau chief Arthur S. Henning stayed mum, and publisher McCormick improbably claimed he had not known about the story until he read it in the paper. White House correspondent Walter Trohan avoided the telephone, accurately deducing that both the FBI and the army were tapping his line. Some Tribune newsmen relied on obfuscation: when asked if a senator or Senate staffer had leaked the plan, an unidentified Tribune writer scoffed, “These ridiculous things may be dismissed from your mind.” Another told agents, “Don’t overlook the cabinet.”

The FBI turned to other newsmen for help, interviewing reporters from various papers. Not all of them liked what the Tribune had done, and some were willing to tell what they knew so long as their names were kept out of it. One staffer at the Washington Times-Herald, also a McCormick paper, was “tickled to death” to help because he didn’t like the paper’s publication of military secrets; he had two sons in the navy.

A few newsmen pointed to an isolationist senator as Manly’s source. Joseph Patterson, McCormick’s cousin and publisher of the New York Daily News, confirmed this. Certain isolationist senators, several reporters said, had “shopped around” to find a news outlet that would give the war plan “widespread distribution.” A reporter for an unidentified New York paper had also been offered the plan, he said, but his editors told him not to have “anything to do with this situation.” Only the Tribune bit.

Several newsmen identified Senator David I. Walsh, a Democrat from Massachusetts, as Manly’s source. An America First supporter, the 69-year-old Walsh had claimed in 1940 that Roosevelt’s foreign policy was moving the country toward “a precipice of stupendous and horrifying depths.”

No copy of the Victory Program had officially been given to Congress, so the ultimate question was who had leaked it to the senator. The culprit, several newsmen told the FBI, was “one of the highest ranking officers of the War Department” and a man of “general officer rank” who had been “loudspoken in advocating the retaining in the United States of the output of American armament factories.” While the newsmen might well have suggested a likely candidate, the FBI reports did not name this general—but the description most closely fit Hap Arnold. Recently promoted to lieutenant general, Arnold was chief of the Army Air Forces and an opponent of Lend-Lease’s diversion of warplanes overseas.

The FBI had promised the cooperating newsmen anonymity and that their information would not be used in court. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover knew there was only one way to build a criminal case, but it required hardball tactics. From late January 1942 onward, he pressed Attorney General Biddle to subpoena Manly before a grand jury and force the reporter to reveal his source. Manly could be jailed for contempt if he refused. Hoover knew this would ignite a firestorm of negative publicity. “(U)ndoubtedly the whole issue of ‘freedom of the press’ will be invoked on behalf of the offending newspapers,” he predicted.

Hoover wanted Biddle to go even further and subpoena Manly’s “congressional source” to strong-arm him into naming the War Department official who had leaked the plan. If the FBI’s information was accurate, this meant grand jury testimony would implicate both a sitting senator and a high-ranking general. This would hardly foster the national unity the Roosevelt administration wanted now that the United States was at war. Besides, the investigation had uncovered no tangible harm to national security, and Biddle deemed provable harm essential for a criminal prosecution. No grand jury was convened and, on May 4, 1942, Biddle ordered Hoover to close the case.

No heads rolled. Arnold remained air force chief, ending the war as a five-star general. Wedemeyer jumped in rank to lieutenant general and was given wartime command of all U.S. troops in China. Manly joined the service in December 1942. The branch he chose? Hap Arnold’s air force—ironically, as an intelligence officer. After the war, he resumed his newspaper career, working for the Tribune until his death in 1970, only months before his planned retirement. Walsh served in the Senate until 1947.

IN 1962, PART OF THE LEAK mystery was solved unexpectedly when former isolationist senator Burton Wheeler published his memoirs and admitted that he, not his colleague Walsh, had given Manly the plan.

On December 2, 1941, Wheeler had been slipped one of the 35 copies of the plan, wrapped in brown paper like a stag film. He and Manly scrutinized it that day at Wheeler’s Washington home, with Wheeler’s secretary taking shorthand notes for Manly. Wheeler returned the document to his source on December 3 so it would be in its original place when Manly’s story hit newsstands the following day. Wheeler said he leaked the plan to embarrass Roosevelt and chose Manly because he knew the Tribune “would give the plan the kind of attention it deserved.”

The person who gave Wheeler the plan, he claimed, was an Army Air Forces captain whom he refused to identify. This captain had leaked secret information to Wheeler previously, which the senator had used in speeches attacking Roosevelt and Lend-Lease. Wheeler said he suspected, however, that “some top-ranking officer or official” had ordered the captain to give him the plan.

Wheeler’s autobiography didn’t tell all he knew. “I would like to have made it a little stronger with reference to some matters,” he wrote to Wedemeyer in 1962, but “felt it better to leave a few things unsaid.”

Privately, he was more candid. He told his son Edward he was certain the captain was a messenger for Hap Arnold. He later told Wedemeyer the same thing, that Arnold had used the captain—“one of his boys low down”—as a conduit. After the war, assistant FBI director Louis B. Nichols confirmed to former Times-Herald correspondent Frank C. Waldrop that Arnold was indeed the high-ranking officer whom the FBI suspected of being the leaker.

What is missing, however, is a motive for Arnold to disclose the Victory Program. Lend-Lease frustrated him, but the Victory Program should have pleased him. In December 1941, the air force consisted of 12,297 planes and 354,161 men. The Victory Program called for 61,800 additional planes and a total strength of 2.1 million men. Also, pending in Congress at the time of the leak was an $8.2 billion defense appropriations bill that would provide funding for the air force. Disclosure of the plan might have riled isolationists and derailed the spending bill.

More recently, in 1987, historian Thomas Fleming advanced the intriguing theory that President Roosevelt himself orchestrated the leak as a way to goad Hitler into declaring war on the United States.

The president knew that only American military intervention could defeat Hitler. He suspected Japan would soon attack American territory, probably the Philippines, and that would get the country into war in the Pacific—but not in Europe. Only a German declaration of war against the United States would suffice. Hitler’s treaty with Japan required Germany to declare war if the U.S. attacked Japan but not if Japan attacked America, so the president needed to convince Hitler that the United States was his true enemy, Fleming believed. As fascinating as this theory is, however, there is no hard evidence to support it.

The identity of the person who leaked the Victory Program will likely never be known with certainty. All the players are gone, and no deathbed confession has surfaced. The story will endure as one of World War II’s last unsolved mysteries, a fertile ground for educated conjecture by scholars and history buffs alike, and a reminder of the bitter political divisions that wracked the country before America joined the world at war. ✯

The German Reaction

The Victory Program got it wrong when it said July 1, 1943, was the earliest date that the United States could launch offensive operations. American troops beat this prediction by nearly a year, invading Guadalcanal in August 1942 and North Africa in November 1942. Germany, however, took the projected date seriously. As soon as Chesly Manly’s story hit the newsstands on December 4, 1941, the German embassy in Washington cabled it to Berlin. Publicly, German spokesmen mocked the plan as the delusions of “some crazy general,” but behind the scenes, no one was laughing. The German general staff saw the story as an intelligence coup and seized on the 1943 date. German war planners believed total victory in the West might be within Germany’s reach if they could neutralize Britain before then. German forces seemed to be on the verge of capturing Moscow after having invaded Russia six months earlier, but Hitler’s generals proposed a drastic revision in strategy designed to knock Britain out of the war before American help could arrive. On December 14, 1941, they recommended that Hitler: (1) cease offensive operations in Russia and leave only a “minimum of forces” to hold defensive positions there; (2) seal the Mediterranean by driving the British out, seizing the Suez Canal, and establishing bases in North Africa and on the Iberian Peninsula; (3) intensify air and submarine attacks on shipping bound for England; and (4) fully man and fortify the Atlantic coastline to prevent any Allied invasion. Initially, Hitler backed this new strategy, but soon reneged. His ego and hatred of Russia—along with Germany’s critical need for Russian oil, crops, and other resources to keep its war machine going—would not let him halt the eastern offensive when his troops were almost within sight of the Kremlin. No part of the new plan was ever enacted. The revised German war strategy may have been as impractical as Nazi spokesmen said the Victory Program was. It’s difficult to see how Hitler could have halted his Soviet attacks and held onto conquered territory there while shifting enough troops to accomplish the rest of the plan. The mere existence of the German generals’ proposal, though, shows how close the leak of the Victory Program came to affecting the course of the war in Europe. —Joseph Connor