Colonel Charles T. Lanham and Ernest Hemingway each had something the other wanted. Their interests merged in 1944 on Europe’s battlefields.

ON JULY 9, 1944, GIs of the 22nd Infantry Regiment, part of the 4th Division, battled south from the foot of Normandy’s Contentin Peninsula. Heavy casualties from D-Day and the subsequent capture of Cherbourg had severely depleted the veteran ranks of the “Double Deucers.” Now relentless U.S. attacks met stubborn counterattacks by fresh, battle-hardened German units. Worse, the Norman bocage—a checkerboard of fields bounded by dense hedgerows—made armored support virtually impossible. The division commander, Major General Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton, had already summarily relieved two of the regiment’s commanders. Amid this furor and disorder, a captain at the 22nd’s forward command post answered a ringing field phone. “I am Colonel Charles T. Lanham,” a voice on the other end announced. “I have just assumed command of this regiment, and I want you to know that if you ever yield one foot of ground without my direct order, I will court-martial you.”

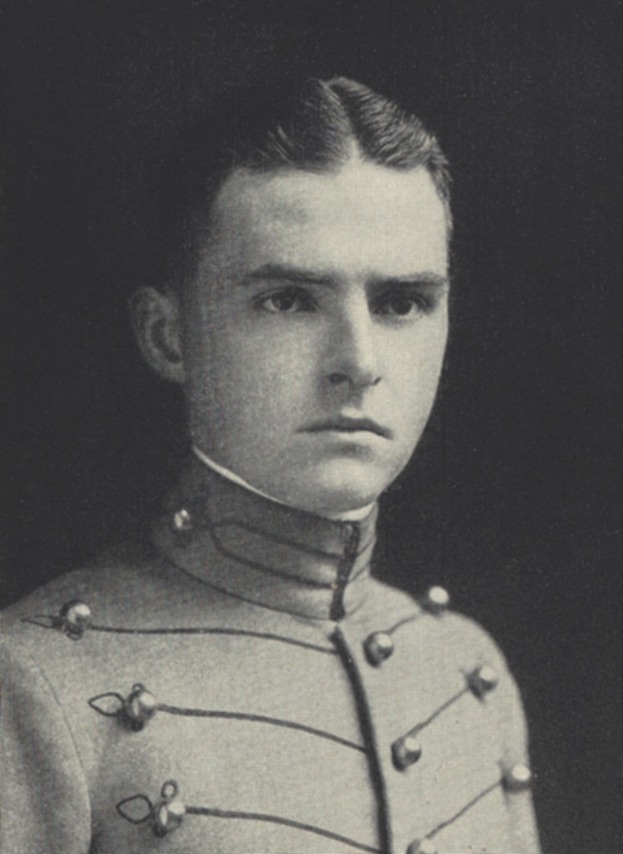

It was the first battlefield command for Lanham, a 41-year-old West Pointer. Why had combat come so late for the trim, gray-haired, bespectacled colonel? Perhaps a clue lay in his profile in the 1924 edition of the West Point yearbook, The Howitzer: “His highest ambitions and greatest aspirations are in the field of literature.”

An odd encomium for a cadet about to embark on an infantry career. Indeed, even as he took the “ground-pounder” path, Lanham—known to most by his plebe year nickname, Buck—wrote and published poetry elegizing the warrior craft. “Soldier,” for example, published in the August 1933 issue of Harper’s magazine, begins:

The stars swing down the western steep,

And soon the east will burn with day,

And we shall struggle up from sleep

And sling our packs and march away.

Following his 1932 graduation from Fort Benning’s Infantry School Company Officer’s Course, Buck Lanham became a military history instructor—an added inducement to think, research, and write. His frequent articles for Infantry Journal, a forum for infantry professionals, eventually caught the attention of George C. Marshall, then the army’s deputy chief of staff.

Lanham wrote the 1939 edition of Infantry in Battle—a “best practices” manual of small unit tactics—at Marshall’s behest before heading off to Hollywood to write and produce training films. By the time Lanham neared 40, he had ripened into a scholar of military literature. It was a valuable commodity to an interwar army struggling to update tactics, strategy, and organization—but a dubious brand to carry into battle.

Since taking command of the 22nd, however, Buck Lanham had displayed more than field-phone bravado. “He was relentless and…ruthless in his pressure for results from his subordinates,” asserted Major Earl W. Edwards, Lanham’s operations officer. “As a combat commander…he was among the very best.”

On July 28, 1944, the reinvigorated Double Deucers joined the lead elements of Operation Cobra, a five-mile-wide breakout south of Saint-Lô involving the 4th, 9th, and 30th Infantry Divisions. Already a force to be reckoned with, Lanham’s GIs rode atop modified Sherman tanks whose front ends were rigged with large cutting blades to smash through hedgerows, “leaping off to spray every swale and thicket with blistering fire,” as author Rick Atkinson described it. The day’s onslaught overran 10 miles of bocage and took 300 POWs. That night, as Lanham pored over maps in the front room of a small farmhouse near Le Mesnil-Herman, a tiny village nine miles south of Saint-Lô, Edwards announced two visitors—one purportedly a “Colonel Colliers from Washington.”

When a bearded, grizzled giant shouldered his way through the narrow farmhouse door, Lanham extended his hand. “Colonel Colliers?”

“I’m no colonel,” replied the visitor. “I’m a correspondent for Collier’s. My name is Hemingway.”

“Ernest, no doubt,” Buck quipped caustically, not immediately recognizing who stood in front of him.

“Yes,” the giant confessed. “My name is Ernest.”

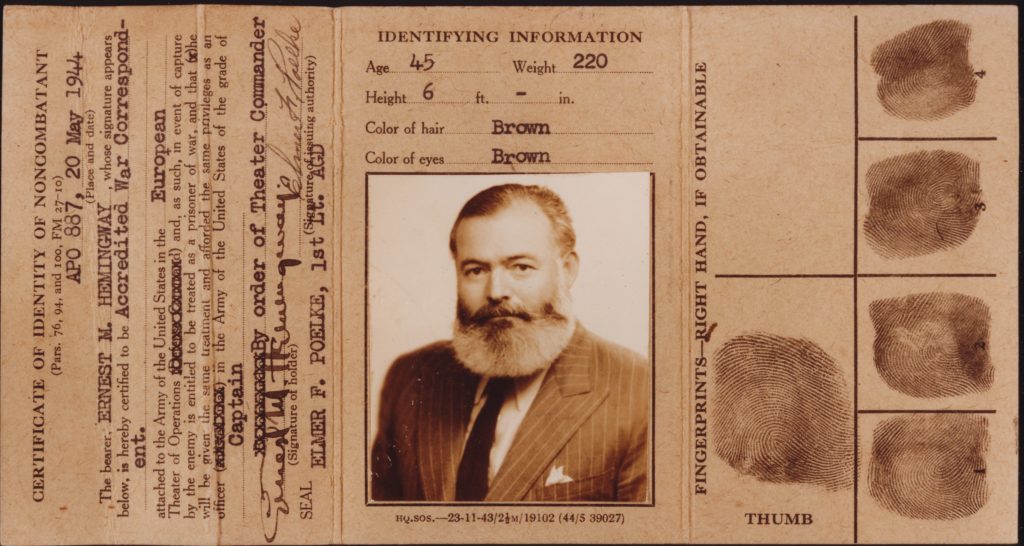

ERNEST “PAPA” HEMINGWAY, the celebrated 45-year-old author of The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, and For Whom the Bell Tolls, had followed a circuitous path to Le Mesnil-Herman. During World War I, Papa had been severely wounded by enemy fire while a volunteer ambulance driver, and he had reported, often under fire, in Spain’s civil war. But America’s World War II entry found him self-exiled on his 13-acre homestead in northwest Cuba. During 1942 and 1943, he alternated between operating the “Crook Factory,” a counterintelligence bureau sanctioned by the U.S. Embassy in Havana to uncover Axis spies and collaborators, and “Operation Friendless,” supported by the Havana branch of the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence: a hunt for German U-boats in the waters off Cuba aboard his 38-foot cabin cruiser, Pilar. Though never getting the opportunity, he envisioned luring U-boats alongside Pilar, then lobbing hand grenades down their open hatches.

Both backwater ventures allowed him to operate on his own terms, decoupled from military chains of command. But as 1943 closed, Papa craved action. Anticipating the Allied invasion of mainland Europe, he tried unsuccessfully to join the clandestine Office of Special Services before eventually settling for accreditation as a war correspondent for Collier’s magazine.

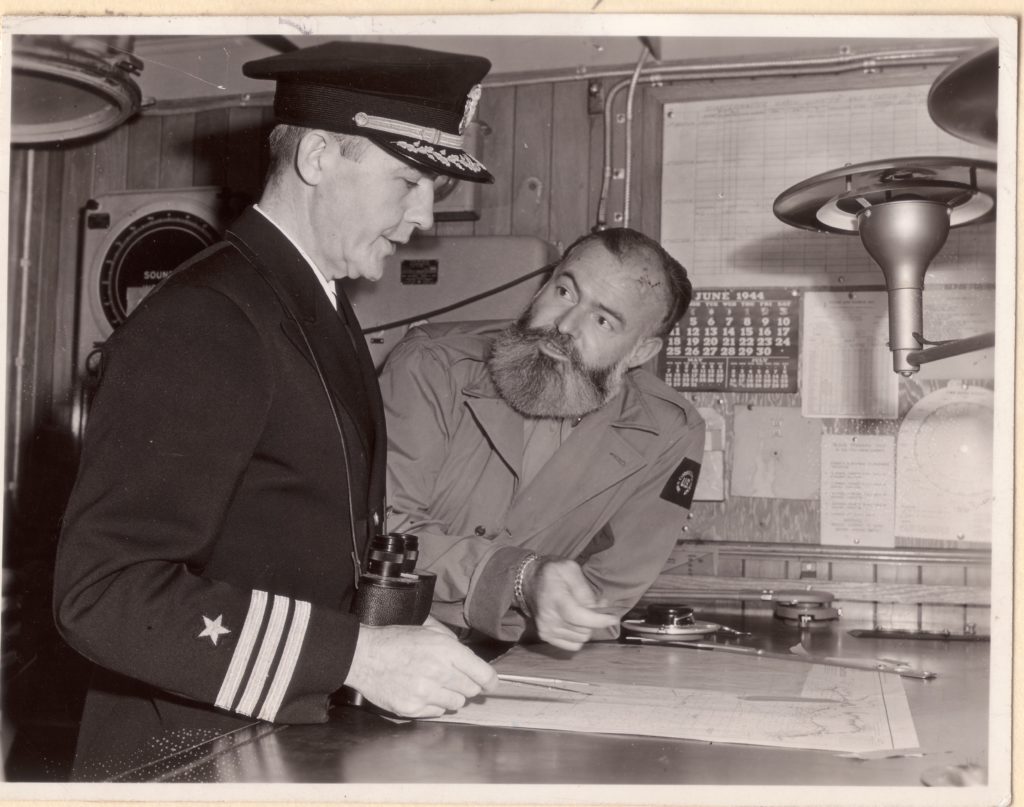

Hemingway arrived in Britain on May 17, 1944. Always a risk-taker living on the edge, he chafed at being a correspondent—subject to censorship and constrained by Geneva Convention rules to observe, not join, the fighting. From the outset, Hemingway’s dispatches put him center stage and strained the limits of reportorial detachment. On D-Day, for example, riding an LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel) off Omaha Beach, he described using binoculars to scout possible landing sites, then intervening when Navy Lieutenant (jg) Robert “Andy” Anderson steered toward peril: “‘Andy,’ I said, ‘the whole sector is enfiladed with machine gun fire…. It isn’t any good.’”

Anderson’s LCVP offloaded its troops successfully, but Hemingway—assigned to the LCVP’s mother ship, not an infantry unit—didn’t actually set foot on Normandy until mid-July. After first checking in with the 4th Armored Division, Papa eventually found his way to Tubby Barton’s headquarters and, ultimately, on July 28, to Buck Lanham’s forward command post. Over the next nine days, Hem-ingway accompanied the Double Deucers on advances south and east toward Saint-Pois, 25 miles from Le Mesnil-Herman. He described it as “a tough fine time with the infantry,” fighting over small hills, along dusty roads, through hedgerows and wheat fields, past burned-out German tanks and “deads” from both sides.

During rare lulls, according to writer Nicholas Reynolds, Lanham wanted to talk about literature and his own writing. Hemingway, however, expressed more interest in battle courage—what Lanham called that “grace under pressure crap.” Nonetheless, Hemingway, the writer who wanted to fight, and Lanham, the fighter who wanted to write, began to forge a bond.

ON AUGUST 2, Papa rode a commandeered, sidecar-equipped motorcycle into Villedieu-les-Poêles, a dozen miles northwest of Saint-Pois; his 29-year-old jeep driver, Private Archie “Red” Pelkey, did the chauffeuring. Hemingway biographer Carlos Baker describes how locals soon steered them to a cellar said to contain SS troops. Bearing hand grenades, Hemingway, well-versed in French and knowing a smattering of German, yelled down in both languages for the occupants to come out. Hearing no answer, he pulled pins on three grenades. “Divide these among yourselves,” Papa shouted, tossing the grenades down.

Not pausing to assess the damage (nor rue this obvious violation of Geneva strictures), Hemingway allowed Villedieu-les-Poêles’s mayor to bestow upon him two congratulatory magnums of champagne. Just as Papa re- turned to his waiting motorcycle, Buck Lanham happened to pull up in a jeep. Gifted one of the magnums, Buck drove off, recalling admiringly how his new friend stood “on the balls of his feet. Like a fighter. Like a great cat.”

For his part, Hemingway now styled himself as “irregular cavalry” conducting forward reconnaissance. According to Baker: “His main job—as he saw it—was to provide information on the disposition of enemy forces far enough in advance to help save the lives of his compatriots.”

FOLLOWING THE NORMANDY breakout, with German forces withdrawing east, the Allies advanced on Paris. Leaving behind the 22nd some 120 miles southwest of the French capital, Hemingway and Pelkey continued east in a jeep supplied by Tubby Barton.

On August 19, on the outskirts of Rambouillet, about 25 miles from Paris, the pair encountered two truckloads of Maquis French Resistance fighters. Informed that the Germans had abandoned Rambouillet, Hemingway and Pelkey followed the trucks forward until they encountered an abandoned German roadblock strewn with fallen trees, wrecked vehicles, booby traps, and mines. When 5th Infantry Division engineers arrived to remove the hazards, Hemingway ordered the French irregulars forward into Rambouillet.

By nightfall, now tacitly in charge of the irregulars, Papa had established a command post at Rambouillet’s Hôtel du Grand Veneur. As in Cuba with the Crook Factory and Operation Friendless, Hemingway, wrote Nicholas Reynolds, had picked up “a loosely organized team, become its leader, and [was leading] it through the fog of war.”

Hemingway’s irregulars occupied Rambouillet for the better part of four days before substantial Allied forces finally moved in. When not guarding against German counterattack, Papa, shedding his war correspondent persona, dispatched patrols; gathered reports on enemy dispositions; grilled German prisoners; and even dispensed grenades, Tommy guns, and pistols from a cache supplied by a nearby American regiment. Crowing that his scouting operations were “straight out of Mosby”—a Confederate cavalry leader known for his stealth and ability to outwit enemies—Papa ignored potential repercussions.

The liberation of Paris kicked off on a rain-drenched August 24. Already situated on the outskirts, Hemingway easily outpaced Lanham’s 22nd into the City of Light. According to Hemingway’s Collier’s dispatch, the spearheading tanks of Major General Jacques Leclerc’s 2nd French Armored Division, attached to Barton’s 4th Division, “operated beautifully”—though the story made sure to mention that French commanders had exploited information “amassed for them” by Hemingway’s band of irregulars.

Once, when hidden German tanks and 88mm artillery cut loose on the column, “the French mechanized artillery slammed into them,” Hemingway reported, knocking out two tanks and all the 88s. An awestruck irregular exclaimed: “C’est un bel accrochage!” and Hemingway blithely translated “accrochage” to Collier’s readers as “what happens when two cars lock bumpers.”

Later, as their jeep passed a burning German ammunition dump, Hemingway noticed Pelkey “laughing heartily at the noise the big stuff was making as it blew.” Papa, however, confessed circumspection: “My own war aim…was to get into Paris without being shot.” Shortly after noon on the 25th he succeeded, soon taking up residence in the deserted and undamaged Hotel Ritz.

BUCK LANHAM’S GIs at last entered the city two days later, but they barely paused to rest. Instead, they joined a massed offensive Rick Atkinson described as: “a great crescent, extending from Brest nearly to Belgium…packed with more than two million Allied soldiers.” Lieutenant General Omar Bradley’s Twelfth Army Group—21 divisions, including Barton’s 4th—crowded the crescent’s lower half.

After staging 50 miles northeast of Paris on August 29, Lanham’s men—now part of Brigadier General George A. Taylor’s Task Force Taylor—set off toward Belgium. Troops and armor raced across flat farmland intersected by small streams and barge canals. In heavy fighting near the Belgian border, GIs destroyed scores of German tanks, captured an ammunition dump, and rounded up 2,000 POWs.

From the French town of Landrecies, 25 miles west of the border, Buck scrawled a short note and dispatched it to Papa at the Hotel Ritz: “Go hang yourself, brave Hemingstein,” it read. “We have fought at Landrecies and you were not there.” Hemingstein (a self-referential nickname conjured by Hemingway) easily deciphered the reference: a quote from France’s 16th-century King Henry IV, jubilantly teasing a brother-in-arms: “Hang yourself, brave Crillon! We have fought at Arques and you were not there.”

Taking the challenge, Hemingway promptly set off north in a jeep driven by a French partisan. Journeying through a region crawling with pockets of bypassed German units, he and his driver braved delays, detours, and a near-brush with a German antitank unit before finally reaching the 22nd’s command post near Le Pommereuil, five miles west of Landrecies, on September 3. Having amply demonstrated his courage and personal loyalty to Buck, Papa accompanied the Double Deucers as they breached Germany’s homeland defenses.

American tanks penetrated Germany near Hemmeres, about 85 miles southwest of Cologne, on the night of September 11-12. This section of the Westwall—what Americans termed the Siegfried Line—lay just east in a thickly forested region called the Schnee Eifel; the vaunted border barrier was thick with bunkers, pillboxes, and antitank obstacles—all well-camouflaged and invariably backed by artillery. Here the Germans defended sacred soil.

On a rainy, gale-swept September 14, after passing through a scattering of unmanned strongpoints, three Double Deucer rifle companies riding tanks and M-10 tank destroyers (TD) assaulted the main barrier. The attack, which Hemingway described secondhand in a Collier’s dispatch, reached the crest of a wooded ridge. Suddenly, as riflemen dismounted and fanned out, the lead TD hit a mine. Soon after, when German 88s opened fire, disabling a tank and a second TD, the attack faltered. Bunched-up infantry sought shelter as the remaining armored vehicles hesitated or retreated.

After witnessing the debacle from a nearby house, Lanham swung into action. “Let’s get up there,” he told Captain Howard Blazzard, a staff officer. When the two reached the hillcrest, Buck approached the wavering skirmishers. “Let’s go get these Krauts,” he shouted. “Let’s kill these chickenshitters, let’s get up over this hill now and get this place taken!”

“He had his goddam forty-five [pistol],” Blazzard recalled, “and he shot three, four times at where the Kraut fire was coming from, and he said, ‘Come on! Nobody’s going to stop here now!’”

Despite heavy casualties (6 officers and 61 enlisted men), the Double Deucers eventually pierced the German defenses. To Hemingway, the action seemed “suitable for screen treatment.” Indeed, as Buck later told him: “Ernie, a lot of the time I felt as though I were at a Grade B picture.”

Later that September came a cinematic postscript. Hemingway and Lanham were dining together when an 88 projectile passed unexploded through the regimental command post. As others—Buck included—scattered for cover, a helmetless Papa continued eating. When another shell passed through, Lanham, not to be outdone, resumed his seat and took off his own helmet. “We continued to argue, to drink, and to eat,” he recalled. Observed biographer Baker: “Although it sounded dirty to say so, [Hemingway] was very happy in this war.”

AFTER THESE FIRST Westwall penetrations, the Allied offensive—starved for fuel and supplies— stalled. With the 22nd back in Belgium to rest and retrain, Papa returned to Paris. There he learned of the Third Army inspector general’s intentions to investigate his activities in Rambouillet. Rival reporters had accused Hemingway of bearing arms and leading troops—thereby risking their noncombatant status. If the charges were upheld, he would face loss of accreditation and a prompt return to the U.S. In mid-October 1944, Hemingway managed to bluff and bluster his way through the IG’s interrogation, admitting afterward: “I denied and…swore away everything I felt any pride in.” His ultimate exoneration came at a heavy cost: disowning his lead role in what he considered the most successful military action of his entire life.

That bitter experience left Hemingway more eager than ever to rejoin the Double Deucers. So when he learned Buck Lanham’s GIs were to resume the Westwall offensive, Papa set off for the Hürtgen Forest, an expanse of dense woods, steep valleys, and waterways a few miles southeast of Aachen, Germany.

Reaching the 22nd command post—a flimsy plywood trailer—on November 15, Hemingway encountered an understandably gloomy Lanham. The Double Deucers’ role in Operation Queen, a massive push to cross the Roer River to seize future Rhine River crossing points, looked to be a reprise of the September Westwall assaults, though this time through even deeper forests, in even worse weather, and against even fiercer German resistance.

The regiment’s main objective was the heavily defended village of Grosshau, a gateway to open country beyond Hürtgen. In assaults that kicked off on November 16, Papa seldom left Buck’s side. On November 22, as German infantry threatened to overrun Lanham’s command post, Hemingway grabbed a Thompson submachine gun to repel attackers. When the two got separated during a predawn assault several days later, wrote Reynolds, Hemingway “dashed through a firebreak where many others had died” in order to reach Lanham. It was a moment Lanham never forgot. Grosshau finally fell on November 29, but only after intense house-to-house fighting.

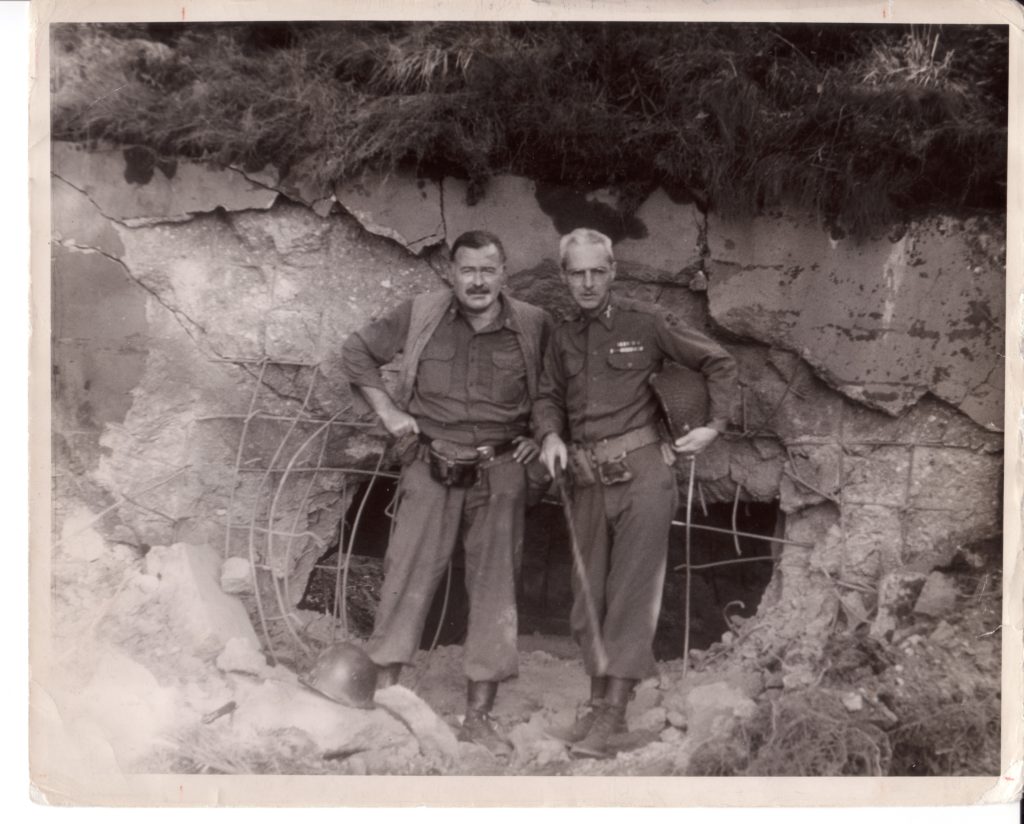

Through it all, Hemingway shared the risks, repeatedly going “outside the wire” with attacking infantry. As a result, his comradeship with Lanham—initiated in Le Mesnil-Herman, then refreshed in Villedieu-les-Poêles, Landrecies, and Pommereuil—emerged fully forged from the Hürtgen crucible. In a letter to his wife, Mary, Lanham said of Hemingway: “He is probably the bravest man I have ever known.”

THE DOUBLE DEUCERS finally withdrew from the fighting on December 3, 1944. As Tubby Barton conceded, “they had attacked until there was no attack left in them.” Altogether, the regiment had suffered 2,773 casualties—85 percent of its 3,257 soldiers.

But the wartime camaraderie of Ernest “Papa” Hemingway and Charles “Buck” Lanham was not entirely over. Hemingway rejoined the Double Deucers in late December for the mop-up phase of the Battle of the Bulge. This time though, exhausted by the record-breaking cold, Hemingway readily confined himself to the regimental command post—a comfortable home near Rodenbourg, a village in Luxembourg.

Beyond the war, and until his death by suicide in 1961, Hemingway’s “band-of-brothers” connection with Lanham (who died, a retired major general, in 1978) never faded. Both had shared the best of comradeship through the worst of combat.

In Across the River and into the Trees, Hemingway’s 1950 novel set in Italy during World War II, U.S. Army Colonel Richard Cantwell, the story’s main character, is a war-scarred amalgam of Hemingway and Lanham. Lanham responded in kind when—some 10 years later, coincident with Hemingway’s 60th birthday—he presented Hemingway with a personally inscribed 200-page mimeographed volume of the Double Deucers’ regimental history. According to biographer Baker, Papa “burst into tears and left the room until he recovered.”

In “Soldier,” well before he met Papa or faced the Germans, writer Lanham imagined war’s worst fate as “The iron wreath of deadly fame.” Then followed a coda which fighter Hemingway could likely endorse:

I see these things, still I am slave

When banners flaunt and bugles blow

Content to fill a soldier’s grave

For reasons I shall never know. ✯

This article was published in the June 2020 issue of World War II.