From its playful origin as a “dandy horse” for idle Europeans, the bicycle has taken on increasingly serious military applications

In August 1887 the French scientific journal La Nature noted favorably the role the velocipede, or bicycle, was beginning to play in European military maneuvers: “For a few years past the Germans have been using the velocipede for the rapid carriage of dispatches, and on this side of the Vosges we have not neglected to put to profit the advantages of an analogous service, a corps of velocipedists having been organized in our army.…Our neighbors across the channel have gone beyond such a use of the velocipede for dispatch sending and have endeavored to use it for the carriage of ammunition.”

In the closing decades of the 19th century technological innovations made cycling more comfortable, more reliable and altogether more practical. Bicycles (aka “wheels”) and their riders (“wheelmen”) became a pop culture craze, and nations around the globe actively studied their application to military operations. For some 130 years the bicycle has remained militarily relevant. Indeed, it has recently emerged as an actual weapon system.

The earliest direct precursor to the modern-day bicycle was the Draisine, conceived in 1817 by namesake German inventor Karl Drais as a fixed-steering vehicle for use on rail lines. Military planners later devised two- and four-wheel versions of the vehicle for railborne reconnaissance and patrols. For off-rail use Drais developed the Laufmaschine (“running machine”), surviving examples of which look familiar to today’s riders. It featured a diamond-shaped frame, the rear vertical rising from the rear wheel hub to form the seat post, and the parallel front vertical rising from the hub of the swiveling front tire into a gooseneck with handles, allowing the rider to steer. Drais’ machine did differ from the modern bicycle in one key aspect—it lacked pedals. Riders used their feet to walk or run the Laufmaschine along the ground. Critics dubbed it the “dandy horse.” Iron-rimmed wheels made for a very rough ride, and pedestrians soon complained of the hazards posed by the veritable sidewalk missiles, spelling the demise of the fad.

Developed in France in the 1860s, the first commercially successful bicycles utilized a crude drive system, with pedals fixed directly to the front wheel hub, as on the modern-day tricycle. Increasing the circumference of the front wheel increased the distance traveled per pedal stroke and consequently the speed, resulting in a bicycle with an elephantine front wheel. Brits dubbed it the “penny-farthing,” as the penny coin of the era was far larger than the farthing coin. Though solid rubber tires and wire-spoked wheels offered a more comfortable ride than that of early “boneshakers,” penny-farthings proved difficult to mount and dangerous to operate.

Back-to-back technological innovations in the late 1880s made bicycling safer and infinitely more practical. Foremost was the development of a chain drive linking central pedals to the rear hub—a power-transfer system not contingent on wheel circumference. Smaller, equal-sized tires placed the rider within reach of the ground, resulting in a vehicle marketed as the “safety bicycle.” In 1888 Scottish inventor John Boyd Dunlop patented the pneumatic tire, which far surpassed the solid rubber tire for comfort. With that the basic elements of the present-day bicycle were in place.

Given the improvements, military planners began to consider the bicycle as an alternative conveyance to the horse, over which it has decided advantages.

After all, a bicycle requires neither fodder nor rest and is generally easier to maintain than a horse.

More critical from a military standpoint, a platoon of cyclists is quieter on the move than a squadron of cavalry.

While the American military was late to embrace cycling, it did so with a passion in the 1890s, due to the confluence of two enthusiasts’ careers. Major General Nelson A. Miles had pioneered military use of the heliograph in the 1870s, and after taking in an 1891 endurance race at New York’s Madison Square Garden, he became a staunch advocate of the bicycle. That fall he ordered the commander of the 15th U.S. Infantry at Fort Sheridan, Ill., to organize a detachment to field test the vehicle. Through the spring of 1892 nine cyclists under Lt. William T. May put the bicycle through its paces. While the results failed to move Miles’ superiors to action, the general later declared presciently, “During the next great war the bicycle, with such modifications and adaptations as experience may suggest, will become a most important machine for military purposes.”

That same year May wrote the field manual Cyclists’ Drill Regulations, United States Army, catching the attention of 20-year-old West Point cadet James A. Moss. In 1894 Moss graduated last in his class from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, drawing an appropriately lackluster infantry assignment in the middle of nowhere (Fort Missoula, Mont.) as a second lieutenant in the 25th U.S. Infantry Regiment, one of four white-officered black regiments in the Army. Fortunately for the lieutenant, the posting placed him in the Military Division of the Missouri, overseen by none other than Miles. The following year Miles was named commanding general of the Army, and in his first annual report to the secretary of war he advocated formation of a dedicated bicycle regiment. In 1896 he granted fellow cycling enthusiast Moss permission to form an experimental bicycle corps and undertake long-distance rides to determine the vehicle’s feasibility for military use.

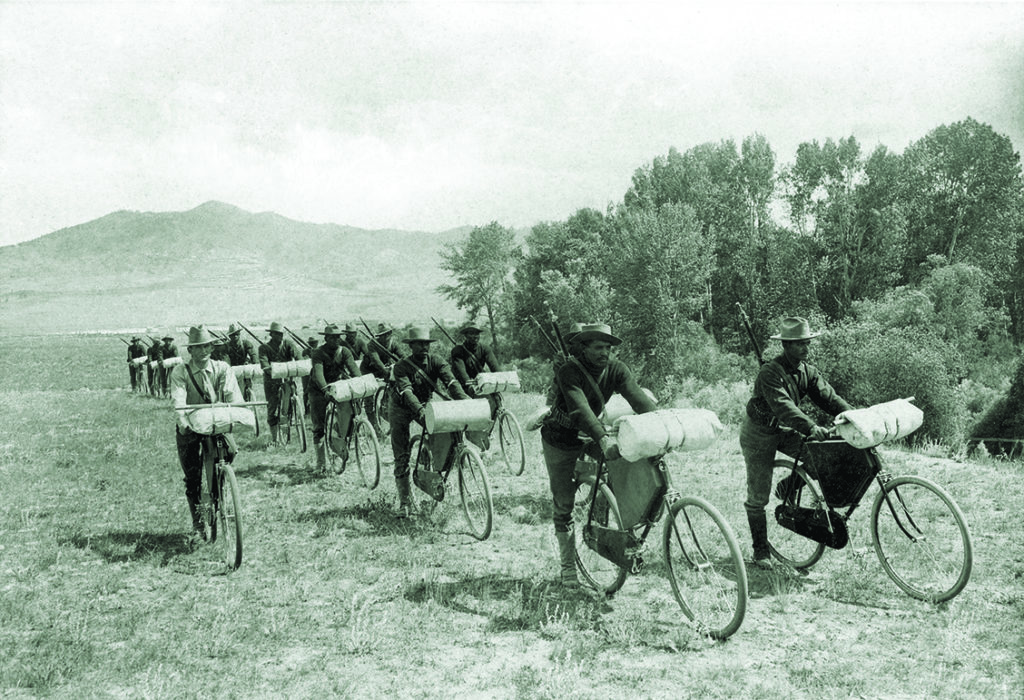

In July 1896 Moss selected eight men, including the indispensable Pvt. John Findley, an adept bicycle mechanic. On August 6, after three weeks of training, drills and increasingly longer rides, the group’s first significant trek took them to and from Lake McDonald in northern Montana, a roughly 280-mile round trip. In August 15, they again departed Fort Missoula, headed southeast to Yellowstone National Park. Strapped to the handlebars of each bicycle—provided gratis by A.G. Spalding Co. of Chicago—was a blanket roll wrapped around a shelter tent and poles, toiletries, spare socks and underwear, while rations hung from a hard leather case secured within the frame. Each fully loaded bicycle weighed just under 60 pounds. Each cyclist also carried a rifle and 50 rounds of ammunition in cartridge belts. The men covered the 400 miles outbound in 10 days, played tourist for five and made the return trip in eight days, arriving at Fort Missoula on September 8.

After a winter spent in consultation with bicycle designers, engineers and mechanics, Moss set his sights even farther in 1897. Departing on June 14, he led a squad of 20 riders accompanied by a surgeon on a 1,900-mile, one-way journey from Fort Missoula to St. Louis. They arrived 40 days later to popular acclaim and considerable media attention before returning to the fort by train. In 1898 Moss proposed to lead an expedition of cyclists across the Great Divide, from Fort Missoula to San Francisco and back again, a total of 2,000 miles. But that spring the Spanish-American War intervened, and the 25th Infantry shipped out to Cuba. The grand bicycle experiment was again placed on hold.

By the turn of the century the militaries of all the world’s leading powers were using the bicycle. Its first major test in combat came on the Western Front during World War I, though not until the closing days of the conflict. Given the static nature of trench warfare coupled with widespread use of the machine gun and industrial-scale artillery barrages, the scope of action for cyclists was initially limited. They often found themselves serving as rear-area scouts, messengers or ambulance carriers, or in a dismounted capacity as menial laborers.

But as the stalemate broke in August 1918 with the Allied offensive known as the Hundred Days, mobile units took on renewed importance. Among those sent into the maelstrom was a battalion of Canadian cyclists.

Within weeks of the United Kingdom’s declaration of war in 1914 the Commonwealth government in Ottawa authorized creation of the Canadian Automobile Machine Gun Brigade—aka “Brutinel’s Brigade,” after commanding officer Brig. Gen. Raymond Brutinel. A forerunner of the modern-day armored division, the revolutionary force included a battalion of cyclists. But on their arrival at the bogged-down Western Front in 1915, the wheelmen found their mobility was of little use. In 1918, in anticipation of the Hundred Days offensive, the mobile forces under Brutinel reorganized as the amalgamated Canadian Independent Force, comprising six units: the 1st and 2nd Motor Machine Gun Brigades (each composed of five 40-gun batteries), the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion, a truck-based 6-inch trench mortar section, a motorcycle battalion and the Canadian Motor Machine Gun Corps Mechanical Transport Company (providing logistical and administrative support). During the forthcoming offensive the mobile units came into their own, and the cyclists finally got into the fight. In the words of Canadian Corps cyclist Captain Wilfred Dancy “Dick” Ellis, “The cyclist battalion cast off their role of corps handymen and engineer’s navvies [excavation crews] and assumed the character for which their training had prepared them.”

At Amiens, once the Canadian 3rd Division had taken its initial objectives, Brutinel’s mobile forces protected the advance’s right flank and provided liaison between cavalry and infantry. On that flank the French were also attacking, but their H hour came some 45 minutes later, leaving the Canadians vulnerable to counterattack in the meantime. The Canadian mobile forces filled the gap until the French caught up. Their fast reaction played a key role in the Canadian Corps’ unequaled 8-mile advance on the first day of the offensive.

In October, as the Canadian advance accelerated, the mobile forces were again parceled out. Said the history of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, “To increase the speed of the pursuit, the 1st and 4th Divisions each received a 69 squadron of the Canadian Light Horse, a company of the Canadian [Corps] Cyclist Battalion, two medium machine- gun batteries and two armored cars.” Weeks before war’s end 4th Canadian Infantry Division commander Maj. Gen. Sir David Watson wrote, “The cyclists have been most valuable in their excellent patrol duties as well as carrying dispatches and securing information regarding enemy movements and positions of our own troops.”

Though they would never mount a charge like their equine counterparts, the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion had demonstrated riders could pedal into the line and fight dismounted as light infantry troops.

During World War II, aside from the technological advances made in motorization and mechanization during the interwar period, the bicycle demonstrated its continuing value.

During Germany’s lightning invasion of Denmark on April 9, 1940, bicycle-mounted Danish infantry platoons met the invaders at several chokepoints. While there is little information in English on their activities, the 2015 Danish war film April 9th depicts one such platoon of cyclists meeting the German assault.

Japan, which had used thousands of bicycle troops during its 1937 invasion of China, also relied on bicycle mounted infantry during its February 1942 invasion of Singapore. In December 1941, just hours before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese invaded British Malaya (present-day Malaysia) from their Indochinese territories. Off the southern tip of the peninsula, Singapore island was home to a major British naval base and well defended from amphibious assault. An attack from its northern, landward front was regarded as impossible due to Malaya’s seemingly impassible jungles. Tokyo exploited that presumption. In company with light tanks, Japanese cyclists traveled the length of the 500-mile peninsula on narrow trails. Strange as it may seem, they had not brought the bicycles with them. As planners were loath to tangle up their amphibious operations with ships’ holds full of bicycles, the riders confiscated the plentiful British Raleigh and BSA bikes from civilians on landing. Arriving by the tens of thousands on the south end of the peninsula by late January, the Japanese flooded across the narrow Johor Strait on barges and collapsible boats, swiftly overwhelmed the fortress and occupied the naval base.

Even the German Wehrmacht, vaunted for its mechanized blitzkrieg, found bicycles indispensable, so much so they seized bicycles across occupied Europe late in the war. Throughout the war the occupying authorities had acted to restrict civilian mobility. From residential registration to curfews, movement was monitored and restricted. A key component of that policy was the requisitioning of civilian motor vehicles, accompanied by restrictions on licensing and registration, augmented by the strict rationing of civilian gasoline supplies. “The bicycle—soon de rigueur for anyone not walking—became even more prevalent,” historian Ronald Rosbottom observes in When Paris Went Dark. “There was no way to forbid them, or Paris would have ceased to function.” For many a bicycle was essential, its loss an existential threat. “Their owners suffered from a paucity of tire rubber and oil,” Rosbottom notes. “A flat tire or stripped gears could be a major event in the life of a worker or a mother responsible for her children’s welfare.” That was as true in besieged London as it was in occupied Paris.

Across Britain airfields suffered from a shortage of vehicles with which to transport aircrews to their waiting planes. Enterprising personnel took to begging, borrowing and stealing bicycles to ride from the briefing room to their bombers. The stealthy cycles came in handy when slipping away for unauthorized visits to the pub.

The stealth nature of the bicycle also made it of particular importance to various European underground movements. The 2014 documentary My Italian Secret highlights road cyclist Gino Bartali, a two-time postwar Tour de France winner who during wartime training rides in full racing attire transported forged documents to the Jewish resistance during World War II, helping save the lives of countless Jews. In his memoir The Bicycle Runner author and chef Gian Franco Romagnoli recounts his youth as a courier for the Italian resistance. He recalls nearly useless synthetic rubber tires and tubes, patches on patches and eventually resorting to a length of garden hose stuffed with sawdust as a tire. He describes the reaction to a final, irreparable flat: “A grown man would simply sit on the curb near the dead, useless vehicle and cry.”

The bicycle played a role in irregular warfare during the far-flung wars of the 20th century, certainly in Vietnam, where bicycles have been common since the early 1900s. In rural areas they are able to navigate footpaths inaccessible to automobiles, such as those atop the dykes between rice paddies. The Vietnamese continue to use the bicycle as personal transportation as well as for haulage, often so laden with cargo its owner has to attach a bamboo extension to the handlebars in order to steer while walking behind the sagging, overburdened frame.

Not surprisingly, bicycles—albeit significantly re-engineered and strengthened to carry up to 500 pounds—were a mainstay on the Ho Chi Minh trail during the three decades of conflict that followed World War II. Until largely supplanted by trucks, bikes were essential during the 1950s and remained so anywhere trucks could not travel. More easily hidden and/or dispersed if targeted by aircraft or artillery, they were a key component of the logistical system that supplied the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese units operating in the south.

In recent decades irregular forces have even weaponized the bicycle. On Sept. 17, 2006, Operation Medusa—a NATO offensive to drive the Taliban from a stronghold in southern Afghanistan’s Kandahar province—was declared complete, and Lt. Gen. David Richards, the British commander of NATO troops in Afghanistan, proclaimed it a “significant success.” A day later, in a gesture of defiance, a suicide bomber killed four soldiers on foot patrol in nearby Panjwai. The chosen delivery system? A bicycle.

Though hardly a new tactic (the IRA employed bicycle bombs on several occasions during the Troubles in Northern

Ireland), the attack illustrates a growing phenomenon. Throughout the strife-riven Middle East bicycles,ridden or pushed, are often laden with innocuous-looking bags and boxes. Replacing such cargo with explosives produces an IED that easily fades into the streetscape. Such devices have since killed or wounded scores of innocent bystanders in Afghanistan and Iraq alone.

Far from fading into irrelevance in its third century as a conveyance, the bicycle has a direct impact on the conduct of warfare. Needing neither fuel nor fodder and only rudimentary maintenance, faster and quieter than a man afoot, it will continue to find military applications. MH

Bob Gordon is a Canada-based historian whose work has been published in that nation, Britain and the United States. For further reading he recommends Bicycles in War, by Martin Caidin and Jay Barbree; Bicycle Troops, by R.S. Kohn; and Riding Into Battle: Canadian Cyclists in the Great War, by Ted Glenn.

This article appeared in the July 2020 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: