That question was certainly on the mind of Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon that season. By default, then, it was also on Lee’s.

Anchored on bluffs lining the Mississippi River, Vicksburg was the key to success in the West for either side as the war entered its third year. The “fortress” city’s topographical dominance gave Confederates the ability to control traffic up and down the river and also served as a vital connection to Southern interests in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

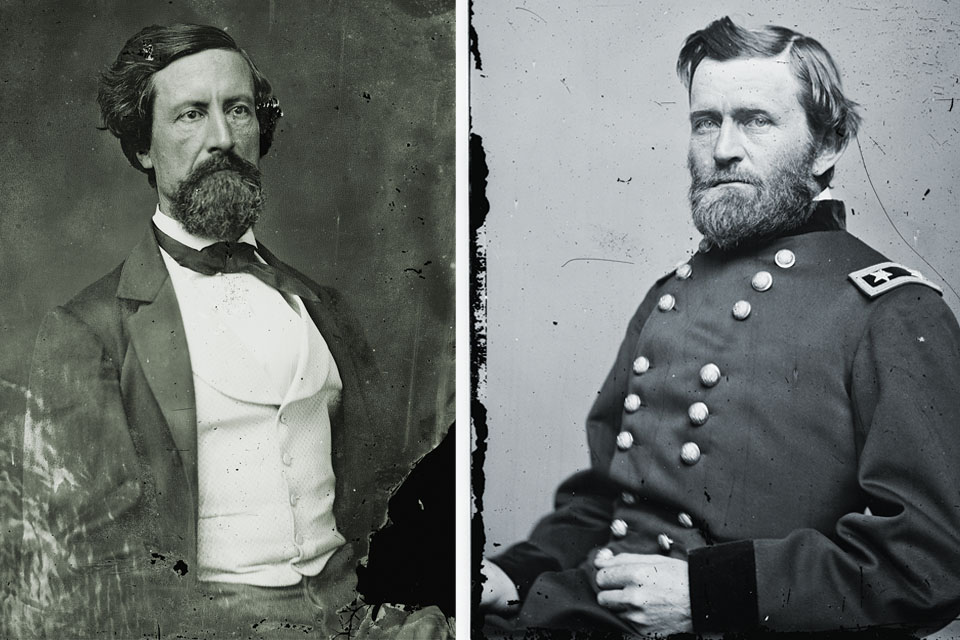

The Union high command in Washington and the region’s army commander, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, were well aware of Vicksburg’s strategic importance. Grant had made stabs at the city for months, to no avail, but his tenaciousness worried the once-confident Mississippians, who demanded a strong response and reliable leadership.

Department commander General Joseph E. Johnston was the highest-ranking Confederate commander in the Western Theater. He was, however, ensconced at the headquarters of General Braxton Bragg in Tullahoma, Tenn., where Bragg’s Army of Tennessee seemed to dominate Johnston’s attention. Meanwhile, the commander of the Vicksburg garrison, Lt. Gen. John Pemberton, was a Pennsylvanian who had thrown his loyalty in with the Confederacy only because of his marriage to Virginia native Martha Thompson—and thus, to some Southerners, could not be trusted. Worse, he had never held such an important field command in his career.

As the situation along the Mississippi looked more and more questionable, Seddon sought solutions. One option would be to send reinforcements directly to Pemberton, another to send them to Johnston, who left Bragg’s headquarters and arrived in the Mississippi capital of Jackson on May 13, with orders from Seddon to take command of troops in the Magnolia State and coordinate the struggle for Vicksburg.

But from where would those reinforcements come?

Vicksburg stood hundreds of miles from Lee’s own position along the banks of Virginia’s Rappahannock River, and Lee had reason to be concerned about the question. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was a Mississippi native who saw Vicksburg as “the nail head that holds the South’s two halves together.” On a more personal note, Davis and his brother both owned plantations right outside Vicksburg. The urge to protect the riverside bastion and deny Federals free, full access to river navigation was strong.

Lee had another reason to be concerned. From a logistical point of view, he already had two divisions on detached duty from his army as winter thawed toward spring in 1863: Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood’s and Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s men, both under the overall command of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. In mid-February, Lee had sent them to southeastern Virginia on a foraging mission to shuffle much-needed supplies back to the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia. Their absence from the Confederate line along the Rappahannock presented a double benefit, too, by lessening the need for those very same supplies on the front. “At this time but few supplies can be procured from the country we now occupy,” Lee told Seddon on March 27 as part of a series of urgent correspondence about the dire state of the army.

Longstreet acknowledged Lee was “averse to having a part of his army so far beyond his reach.” Detached as they were from Lee’s immediate control, the two divisions looked like tempting chess pieces that Seddon could move across the Confederate board to Vicksburg. Complicating matters further, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s 9th Corps shifted to the Western Theater and advanced on Knoxville, Tenn., increasing the need for Confederate counterforces out West.

Could reinforcements “safely be sent from the forces in this department,” Seddon inquired of Lee on April 6, going so far as to muse aloud whether “two or three brigades, say of Pickett’s division” could be spared. “[T]hey would be an encouraging re-enforcement to the Army of the West,” he stressed.

No one seemed eager to get on Lee’s bad side, though; his fiery temper, usually kept hidden under a courtly exterior, was an open secret. Besides, Lee had strung together impressive victories since assuming command in June 1862, so he had earned a certain amount of deference. “I know…that your army is largely outnumbered by the enemy in your front, and that it is not unlikely that a movement against you may be made at any day,” Seddon admitted. “I am, therefore, unwilling to send beyond your command any portion even of the forces here without your counsel and approval.”

Lee responded on April 9 with a letter that demonstrated he, too, had his eye on the chessboard. “I do not know that I can add anything to what I have already said on the subject of reinforcing the Army of the West,” he opened before offering a string of suggestions. Just as Seddon had suggested a Pickett-for-Burnside shift west, Lee countered with a corresponding shift of troops from southwest Tennessee. “If a division has been taken from Memphis to re-enforce [Union Maj. Gen. William] Rosecrans, it diminishes the force opposed to our troops in that quarter,” Lee pointed out, urging offensive action that might tie down Rosecrans’ reinforcements and indicating that rumors of a Federal troop shift along the Tallahatchee River would free up Confederate troops there. He also suggested “judicious operations” in the West that could occupy Burnside, which would do more to relieve pressure on Johnston than sending more troops to Tullahoma would.

Seddon, as secretary of war, certainly had his pulse on these developments more so than Lee, who got them second- and third-hand in his camp in Fredericksburg. But Lee’s attention to them demonstrates the larger strategic view he had beyond his own army, which served as a protection for his army. His big-picture view served his operational interests.

And Lee’s army did have immediate concerns to think about. Rumors circulated everywhere that Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, on the far side of the Rappahannock, was preparing to shake the Army of the Potomac from its winter slumber. Lee set a May 1 deadline, determining to take the offensive himself if Hooker didn’t do something by then. That, too, could help address Seddon’s concerns out west. “Should Genl Hooker’s army assume the defensive,” Lee suggested, “the readiest method of relieving the pressure upon Genl. Johnston…would be for this army to cross into Maryland. This cannot be done, however, in the present condition of the roads….But this is what I would recommend if practicable.” Already Lee was looking north of the Mason-Dixon Line, foreshadowing events that would lead to the Battle of Gettysburg.

Lee admitted that Pickett’s men seemed to offer an easy fix for Seddon, but he warned the secretary not to be deceived. “The most natural way to reinforce Genl Johnston would seem to be to transfer a portion of the troops from this department to oppose those sent west,” he admitted, “but it is not as easy for us to change troops from one department to another as it is for the enemy, and if we rely on that method we may be always too late.”

As events would tell, this proved a self-fulfilling prophecy. By not shifting troops, Lee’s “Better never than late” logic assured there would be no reinforcements at all. For a man once described as “audacity itself,” this abundance of overcautiousness seems curious.

Lee’s pessimism is easily explained by the fact he had a vested interest in keeping Pickett’s troops attached to his army. Longstreet already felt he didn’t have enough troops to robustly carry out his foraging mission, Lee informed Seddon. “If any of his troops are taken from him,” he explained, “I fear it will arrest his operations and deprive us of the benefit anticipated from increasing the supplies of this army.”

The flurry of correspondence between the two over the previous weeks had clearly laid out the case for Lee’s supply concerns, so this comment was no lame excuse suddenly pulled out of thin air. Furthermore, Seddon had attributed the supply urgency to “impediments to their ready transportation and distribution,” admitting in particular, “[O]ur railroads are daily growing less efficient and serviceable.” To depend on those railroads to quickly shift troops to the West might be asking for trouble.

Lee knew this well enough, too, but instead of closing his letter by saying “check mate,” he deployed his usual rhetorical deference. If Seddon thought it “advantageous” to send troops to the West, “General Longstreet will designate such as ought to go.” Couched in such terms, Lee knew Seddon would not find it advantageous and, better, would think it his own idea.

Like his parries with the Army of the Potomac, though, Lee’s victory on the Vicksburg question would be temporary.

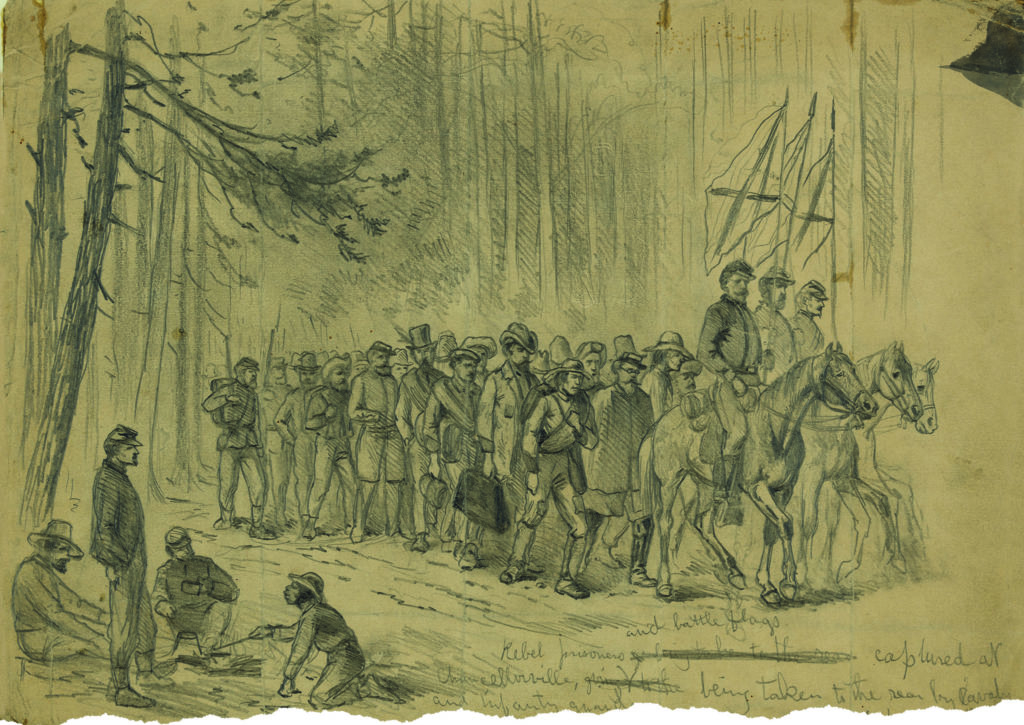

As rumor foretold, Hooker’s army did rumble to life, and the two forces clashed at Chancellorsville, Fredericksburg, and Salem Church from April 30 to May 4. Hooker slipped away on the night of May 5, giving Lee little time to assess his army’s condition before he received another message from Richmond about events in Mississippi.

Even as Lee had beaten back Hooker at Chancellorsville, Grant had begun his spring campaign against Vicksburg in earnest. On April 29, Grant landed two of these three corps on the east bank of the Mississippi at Bruinsburg, south of Vicksburg, then fought his first action of the campaign two days later just a few miles inland at Port Gibson.

On May 6, with Grant moving about the Mississippi interior, Pemberton pleaded with Richmond for reinforcements. “The stake is a great one,” he told Seddon. “I can see nothing so important.” Davis responded the next day: “You may expect whatever is in my power to do.” By that time, he and Seddon had directed General P.G.T. Beauregard, in command of the military district that included Charleston and Savannah, to send reinforcements. Those 5,000 men boarded trains on May 6, and lead elements began arriving in Jackson by May 13, where they would rendezvous under Joe Johnston’s leadership for Vicksburg’s relief.

Davis had explicitly ordered Johnston to Mississippi as an answer to a call from several prominent citizens, including editors of the Jackson Mississippian newspaper. The people did not have “confidence in the capacity and loyalty of Genl. Pemberton, which is so important at this junction, whether justly or not…” the editors wrote in a private letter to Davis on May 8. “Send us a man we can trust,” they pleaded, “Beauregard, [Maj. Gen. D.H.] Hill or Longstreet & confidence will be restored & all will fight to the death for Miss.”

Lee himself was not an option. On the angst-filled evening of April 20, 1861, when he decided to decline Lincoln’s offer to command U.S. forces in the war, Lee resolved, “Save in the defense of my native State, I never desire again to draw my sword.” Sincere as that vow was, he ended up stretching “defense of Virginia” enough to include an invasion of the North in the fall of ’62, and even now he contemplated stretching it again for another. Most important, Lee’s vow reflected his Virginia-centric view of the conflict and his role in it. As a professional soldier, he no doubt would have obeyed any direct order to go west, but as a wily negotiator who knew better than anyone how to manage his own president, he surely would have found a way to make Davis see things his way.

But if Lee wasn’t going anywhere, Seddon at least wanted to shift Pickett’s Division westward—and said so in a May 9 dispatch. Lee was simultaneously deferential and oppositional in his reply the next day: “The distance and the uncertainty of the employment of the troops are unfavorable. But, if necessary, order Pickett at once.”

Within that reply, Lee included a stark assessment: “[I]t becomes a question between Virginia and the Mississippi.” Seeing the note, Davis informed Seddon, “The answer of General Lee was such as I should have anticipated, and in which I concur.” That fairly blunt comment is often taken to suggest Davis agreed with Lee’s priorities, but what the president was in fact acknowledging was that the shortage of resources in the face of twin crises created an unfortunate binary choice.

Lee followed his short dispatch to Seddon with a longer one later in the day. He blamed the delay on the garbled transmission of Seddon’s telegram, which couldn’t be “rendered intelligibly” until nearly noon. It could be, though, Lee needed a little time to think through his response. He did, after all, have much vying for his attention, including the aftermath of battle and the deteriorating condition of trusted subordinate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, who would die that very day.

Lee’s reply laid out careful arguments against any move to Mississippi. Sincerely meant at the time, the note now teems with unfortunate irony when read with hindsight.

“If you determine to send Pickett’s division to Genl Pemberton,” Lee wrote, “I presume it would not reach him until the last of this month. If anything is done in that quarter, it will be over by that time, as the climate in June will force the enemy to retire. The uncertainty of its arrival and the uncertainty of its application cause me to doubt the policy of sending it. Its removal from this army will be sensibly felt….I think troops ordered from Virginia to the Mississippi at this season would be greatly endangered by the climate.”

Lee predicted that any action in Mississippi would be over by month’s end, which, of course, would not be the case. Instead, by month’s end Grant was just settling into a siege. Even factoring in the questionable condition of the railroads and the distance to travel, it’s reasonable to think Pickett’s men could have arrived in the Magnolia State in time to be of use. The timely movement of Beauregard’s men from South Carolina and Georgia demonstrated as much. Certainly, the vulnerabilities of the railroad, called into stark relief by the supply issue, offered cause for realistic caution, but a little more audacity would not have hurt.

Pickett’s arrival would have added 7,500 troops to Johnston’s assembled force of 15,000 men in Jackson—a significant threat to Grant’s isolated army. In fact, one reason Grant rushed into assaults on May 19 and 22 was that he had one eye on Johnston operating in his rear and feared an attack from behind. Johnston never made a move, but perhaps an additional 7,500 men would have inspired action.

Lee’s May 10 letter also became ironic because he predicted “the climate in June will force the enemy to retire.” Of course, Grant ended up doing no such thing, opting to “outcamp” the besieged force in Vicksburg for 47 days. One of Lee’s underlying assumptions proved wildly off the mark, which Seddon had suspected from the beginning: “Grant was such an obstinate fellow that he could only be induced to quit Vicksburg by terribly hard knocks.”

Of course, Lee had a vested interest in keeping his army intact. “Unless we can obtain some reinforcements,” he told Seddon, “we may be obliged to withdraw into the defenses around Richmond. We are greatly outnumbered now….The strength of this army has been reduced by the casualties of the late battles.”

Indeed, even in victory, Chancellorsville had cost Lee 13,460 men. Compounding those losses, intelligence suggested Hooker’s army was already replenishing its own casualties. “Virginia is to be the theater of action, and this army, if possible, ought to be strengthened…” Lee wrote to Davis on May 11, underscoring the point he had made to Seddon the day before. “I think you will agree with me that every effort should be made to re-enforce this army in order to oppose the large force which the enemy seems to be concentrating against it.”

In that same letter, noting that troops from the Departments of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida had been sent to Vicksburg—the 5,000 men Beauregard had shipped out—Lee let slip an idea that had weighed increasingly on his mind since Chancellorsville. “A vigorous movement here would certainly draw the enemy from there,” he said.

Lee didn’t just want reinforcements for defense. He was thinking about taking the fight to the Federals.

With Stonewall Jackson struggling to recover from his wounding and with James Longstreet not yet back from Suffolk, Lee felt the loneliness of command even as he tried to puzzle out what to do next. How should he follow up Chancellorsville? What should he do about the army in light of Jackson’s absence? What could he do to replace the tremendous battle losses his army had sustained? Yes, even perhaps, how might Vicksburg tie into his own plans?

“There are many things about which I would like to consult Your Excellency,” Lee wrote Davis on May 7, “and I should be delighted, if your health and convenience suited, you could visit the army.” Promising Davis a comfortable room near his headquarters, Lee wrote, “I know you would be content with our camp fare.”

Davis was too sick to travel, however, and with the wounded Army of the Potomac lurking on the far side of the Rappahannock, and with his own army and officer corps still reeling from its recent bloodletting, Lee did not yet feel comfortable slipping away to Richmond. He’d have to brood over his plans in solitude.

As it happened, Longstreet would have been happy to discuss things. Chancellorsville had triggered a hurried recall of the First Corps commander and his two divisions, but the fighting ended before they could make it back. Lee subsequently ordered his Old Warhorse not to stress his men with a forced march.

On the trip north, Longstreet had plenty of time to chew over the Confederacy’s overall strategic situation. Since at least late January, he had contemplated moves where one corps of the Army of Northern Virginia would hold the line at the Rappahannock while the other corps would operate elsewhere—and his operations around Suffolk had confirmed the idea’s viability. He longed to “break up [the enemy] in the East and then re-enforce in the West in time to crush him there.” By May, Longstreet had a particular eye on Vicksburg. “I thought that honor, interest, duty, and humanity called us to that service,” he would later say.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Traveling ahead of his divisions, Longstreet arrived in Richmond by train the evening of May 5 and spent the 6th conferring with Seddon. What if, the secretary of war floated, we sent Pickett’s and Hood’s divisions toward Mississippi and not north to the Rappahannock?

Longstreet did Seddon one better. Rather than send troops to Vicksburg where they would move against Grant directly, he suggested reinforcements concentrate instead in Middle Tennessee under Johnston—reinforcements that would include Hood and Pickett, with Longstreet himself along for good measure. Johnston could then combine with Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee in a move against Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland encamped in Murfreesboro. “The combination once made should strike immediately in overwhelming force upon Rosecrans, and march for the Ohio River and Cincinnati,” Longstreet argued. That sudden dire threat would force a Federal response. “Grant’s was the only army that could be drawn to meet this move, and that the move must, therefore, relieve Vicksburg,” he concluded.

Longstreet’s plan reflected the same principle Lee had articulated in April while contemplating a move on Maryland, ultimately shelved because of the muddy spring roads. A serious movement north would panic state governments and the Lincoln administration into a response that would sap Union operations of any initiative and momentum while they dealt with a Confederate invasion.

Lee’s Old Warhorse was not being disingenuous toward his commander in proposing this plan. As soon as he reported to Lee on May 9, he presented his idea for Vicksburg’s tangential relief to Lee and asked for “reinforcements from his army for the West, to that end.”

As Longstreet recalled, Lee “reflected over the matter for one or two days.” This was either a generous or a forgetful retelling. The same day Longstreet pitched the idea, Seddon’s garbled telegram arrived asking to transfer Pickett’s Division west—a telegram no doubt inspired by Seddon’s conversation with Longstreet. Lee didn’t respond until May 10, and during that time, he sent for Longstreet for further discussion.

“I thought we could spare the troops unless there was a chance of a forward movement,” Longstreet explained to a confidant. “If we could move of course we should want everything that we had and all that we could get.”

Indeed, Lee had begun thinking of moving, not defending, and his reply to Seddon suggests a mind firmly made up. “To that end he bent his energies,” Longstreet recalled. “His plan or wishes announced, it became useless and improper to offer suggestions leading to a different course.”

But even as Lee settled on his plans—and set his mind about reclaiming Longstreet’s two divisions—John Pemberton was penning frantic letters to Richmond about Grant’s movements through the Mississippi interior. Davis, still ailing, was largely silent in reply, but he confided “intense anxiety over Pemberton’s situation” despite public confidence.

In fact, the timing of Grant’s river crossing could not have worked out better for him in relation to events in the East, which presented more urgency to Richmond because of their proximity. Chancellorsville, on Richmond’s doorstep compared to the Magnolia State, sucked up all the oxygen. Davis’ illness kept him uncharacteristically passive, and even before he recovered, Stonewall Jackson’s May 10 death provided additional, mournful distraction. Davis and Seddon did agree to send reinforcements west from Beauregard, but at a time when additional troops might have also come from the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee was feeling his oats after his Chancellorsville victory.

Lee finally had his conference with Davis in Richmond on May 15, arriving on a day of “calamity,” according to Confederate clerk John B. Jones. A fire had torn through the Tredegar Iron Works and Crenshou’s woolen mill, mostly destroying them, and news had just arrived of Grant’s capture of Jackson. “[Vicksburg] may be doomed to fall at last,” Jones wrote. If so, it would be “the worst blow we have yet received.”

Lee, Jones wrote, looked thin and a little pale, while Davis, just back to work, was “not fully himself yet.” Lee was so alarmed at the president’s frailty, in fact, he wrote upon his return to Fredericksburg, “I cannot express the concern I felt at leaving you in such feeble health, with so many anxious thoughts for the welfare of the whole Confederacy weighing upon your mind.”

Although no record exists of the discussion that day, the result of the Lee-Davis confab was the Gettysburg Campaign—or at least the general outlines of it. “It appears, after the consultation of the generals and the President yesterday, it was resolved not to send Pickett’s division to Mississippi,” Jones observed on May 16.

In the weeks that followed, Davis perhaps felt buyer’s remorse for his troop allocations. After two failed assaults on Vicksburg, Grant besieged the city instead. “The position, naturally strong, may soon be intrenched,” said Davis, conceding that Grant had the additional advantage of connecting his army with gunboats and transportation on the Yazoo River to the north of Vicksburg, allowing Federals to bring in more troops, supplies, and big guns—none of which were now available to the cut-off city.

“It is useless to look back,” Davis told Lee, “and it would be unkind to annoy you in the midst of your many cares with the reflections which I have not been able to avoid.” Davis had put the needs of the Confederacy ahead of his home state but now could not stop wondering whether he had prioritized the crisis properly. What if Lee had sent troops to Vicksburg? Would it have made a difference? Was the gambit worth it?

Lee’s foray north of the Mason-Dixon Line was about to begin. The answers to Davis’s questions awaited.

Adapted from The Summer of ’63: Vicksburg and Tullahoma, edited by Chris Mackowski and Dan Welch (Savas Beatie, 2021).