Roy Knabenshue’s dirigible offered sightseeing flights around Los Angeles and Chicago, garnering frequent press coverage, then disappeared without a trace.

Early in 1912, pioneer aviator Augustus Roy Knabenshue shared an idea with fellow birdman Charles Willard for building an airship that could carry 10 to 12 passengers on regular trips. The two had been friends since at least September 1909, when at a flying exhibition in St. Louis’ Forest Park they came up with the idea of organizing what would become the legendary 1910 Dominguez Air Meet.

Knabenshue first achieved fame when he flew Thomas Baldwin’s California Arrow airship at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, where he won the grand prize for his record flights. He had been a professional balloonist since 1900, when he bought his first balloon and started offering flights at county fairs. His socially prominent family opposed the venture, and Knabenshue said, “I could not engage in a business that would lower and drag the family name through the mire,” so during those early flying days he went under the name Professor Don Carlos.

By 1912 Knabenshue had designed and built several successful airships, slowly increasing their size and capacity and establishing many aviation firsts, including the first powered flight in the U.S. with multiple passengers. Meanwhile he had attracted the attention of the Wright brothers, who hired him to plan exhibitions for their pilots in training.

In 1908 Stanley Beach, aviation editor of Scientific American and founder of New York’s Aeronautic Society, invited Willard to help him build an airplane. The Beach-Willard monoplane was ultimately a failure, but it gave Willard valuable experience and spurred his interest in aviation. He then became the Aeronautic Society’s exhibition pilot, taught by Glenn Curtiss (in a single three-hour lesson) when the society purchased the Golden Flyer biplane from him. Curtiss later hired him to be part of his flying exhibition team.

Knabenshue had recently left his job as manager of the Wright brothers’ flight exhibition team when Willard quit flying for Curtiss. Willard agreed to design the new passenger airship, though his involvement in the project seems to have ended with that initial design.

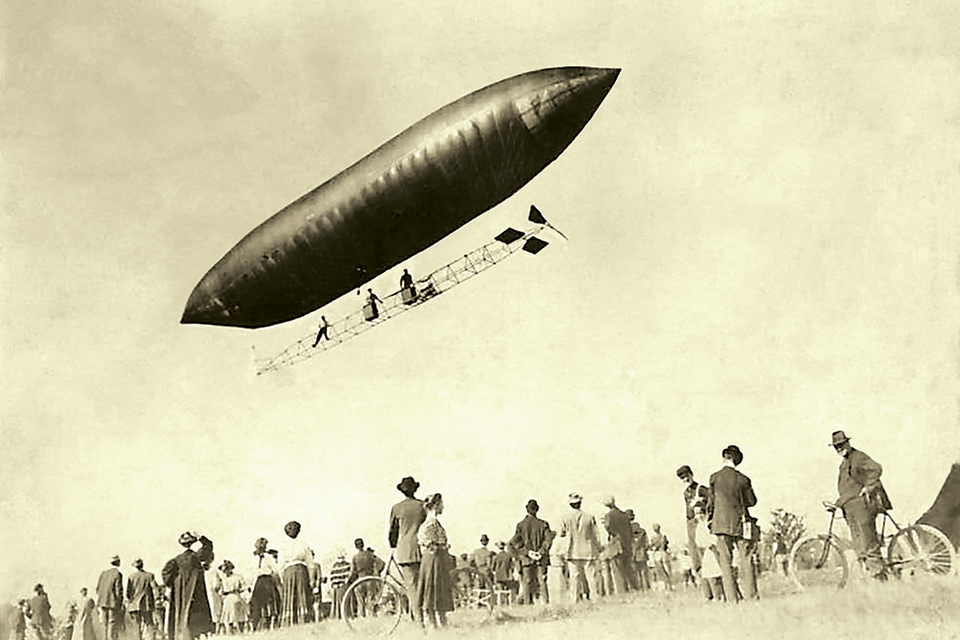

On September 11, 1912, the East Oregonian announced: “Roy Knabenshue, aviator, left Los Angeles for Akron, Ohio, where he will begin construction of an airship for passenger service between Los Angeles and the beaches and Mount Lowe.” Eight months later the completed airship was transported to Pasadena and housed in a hangar on South Marengo Avenue. The construction cost was more than $40,000.

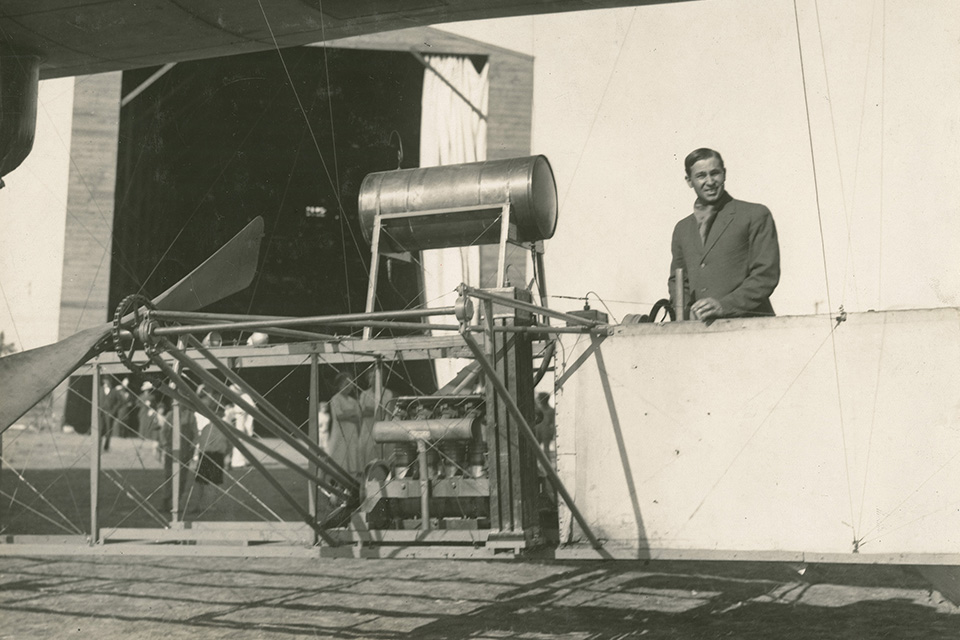

When first built, the entire gondola framework was covered with cloth and the airship featured forward and rear biplane elevators. The first flight, on April 15, 1913, revealed some issues to fix. The forward elevators were removed, the cloth was stripped from most of the framework and significantly larger rudders were installed. The ship flew successfully for 45 minutes on May 4.

By November 1913 the airship was making regular sightseeing flights to Los Angeles and back. The 10-mile roundtrip took 20 minutes. On November 1 the San Francisco Call whimsically reported: “Since Roy Knabenshue began making flights here in a dirigible balloon it is noticed all the laying hens have gone on strike. Eggs are now imported from Monrovia.” Granted, no one, including chickens, was yet accustomed to flying machines regularly passing low overhead, so perhaps there was something to the story.

On November 24, while returning from a flight to Los Angeles with five passengers, the airship’s engine suddenly stopped due to a burst water pipe. The ship began to rise but Knabenshue walked up to the bow and used his weight to point the nose down again. It almost plowed into an orange grove before enough ballast could be released to clear the trees. Moments later spectators grabbed the anchor rope and towed the airship to its hangar.

The following year, Pasadena (it is unclear when exactly it was named, as early newspaper coverage simply referred to a “big dirigible”) flew regularly from its namesake city to Santa Monica, Los Angeles, Long Beach and back. One notable early passenger was Arthur E. Raymond, son of the owner of the nearby Raymond Hotel. The 15-year-old often helped to handle the ship on the ground, and finally on a slow day Knabenshue took him for a ride. This sparked his lifelong enthusiasm for aviation, and Raymond eventually became the designer of the legendary Douglas DC-3 and DC-8 airliners.

A flight on March 6, 1914, carried a wireless apparatus operated by H.D. Hayes, director of the Los Angeles YMCA school of wireless instruction. Hayes managed to stay in constant contact with a wireless station in San Pedro, 40 miles away.

On March 7 Collier’s magazine noted, “The sight of aircraft has become so familiar in Pasadena, Cal., that Roy Knabenshue, captain of the dirigible which docks in that port, observes that school children playing in Pasadena’s streets often do not trouble nowadays to look up when the big airship glides by.” It was no mean achievement to have safely flown over the city so regularly that even children were becoming jaded.

In April Knabenshue and Pasadena appeared in the Universal Studios picture Won in the Clouds, a “three reel special feature.” Marie Walcamp, the original action movie heroine, played the female lead, with Knabenshue appearing as himself. The film featured “a climax that fairly crashes!” noted Kansas’ Chetopa Advance.

On May 21, while staying in Washington, D.C., Knabenshue gave an entertaining interview to the Washington Herald newspaper. Still a dedicated ballooning enthusiast, he told the reporter: “It is the king of sports….There is nothing to compare to it. When I get through, all a person will have to do is go out in the garden, unhitch the family balloon, and go to see father in the next county. I hope to see the day when a self-respecting family will no more dare to be without a balloon than without a family skeleton.”

By spring of 1914, the pool of wealthy passengers who could afford the $25 ticket for trips in Pasadena was getting shallow, and Knabenshue was planning his next venture with the airship. Aeronautics magazine reported, “The ship has been in operation in Los Angeles and vicinity since August of last year; has made hundreds of trips with passengers, and was not deflated until the 1st of May when it was packed to ship to Chicago.” The magazine noted that Knabenshue might bring his “10-man dirigible” to New York after he was done in Chicago.

After Pasadena was packed up and shipped to Chicago on May 1, it was ready to fly again by the middle of June. The airship’s rear biplane elevators were replaced with triplane elevators, and the passenger gondola refitted. The airship was renamed White City after the amusement park in which it was now based. The ticket price was still $25. Knabenshue carefully documented each flight—passengers signed a form that read, “I, the undersigned, hereby express my willingness to undertake all risks in connection with the Airship Flight which I am about to take and fully release The White City Construction Company and A.R. Knabenshue from all liability.” Always cautious, Knabenshue canceled flights when he judged the wind too strong.

On June 17 White City made its first Chicago flight, a 24-minute trip over the city’s parks and Lake Michigan with eight passengers aboard. It flew for an hour and a half on June 26. “The airship left White City shortly after 4 o’clock,” Aero and Hydro reported. “Within 30 minutes it had passed Twelfth Street. It followed the lakeshore and turned loopward just north of Grant Park. It circled over many of the famous skyscrapers, and the seven passengers looked down into the ‘wells’ of the big buildings. A photographer in the dirigible took a number of views during the trip.” The passengers that day were four women, two men and, in the back, a movie camera operator. It wasn’t unusual for movie cameramen to be called “photographers” at that time—films were “reels of pictures.” White City flew low and slow and the cameraman took clear footage of buildings, ships, railyards, automobiles and people, and of the airship being taken out of its shed and put back into it. This film eventually vanished into the National Archives and was only recently rediscovered there by Chicago Tribune reporters, but in the meantime, it would play a very important role in the next phase of Roy Knabenshue’s career.

At some point in July, Knabenshue took his mother, father and wife for a flight. On July 11, in a publicity stunt, “Roy Knabenshue with four passengers in his huge dirigible and Jack Vilas in a hydroaeroplane, played tag over Lake Michigan, the smaller craft circling the larger one many times,” reported the South Bend News-Times. This was the last press mention of the airship, after which its fate is unknown. It was not destroyed in an accident; that certainly would have been noted. And if Knabenshue sold it, there is no record of it flying anywhere else later.

In 1916 Knabenshue made a presentation at the Navy Department in Washington of the film taken from White City, greatly impressing the gathered military representatives. Later that year, he received an order from the Army Air Service for a “special spherical balloon” and 25 observation balloons. He started the Knabenshue Manufacturing Company and leased a factory in Northport on Long Island, where he successfully fulfilled the contract.

The following September, with famous French engineer Henri Julliot (builder of the Lebaudy airships Jaune, La Patrie, La République and others) in charge, the B.F. Goodrich Company completed its first two patrol blimps for the U.S. Navy. The Navy required a strenuous acceptance test flight, to be conducted at night. Enter America’s most experienced airship pilot, Roy Knabenshue. The eight-hour flight “over a big city” (kept secret, but likely Los Angeles) was a resounding success and the Navy accepted the blimps. This would be the last hurrah of his flying career.

In 1924 Knabenshue tried to return to airships, this time rigid. A blueprint was drawn in March for the Knabenshue Aircraft Corporation airship California. In 1926 he told the press the “work of design and developing plans” had taken most of his time for the past five years. A large scale model of the airship was built the following year, and Knabenshue promoted the idea of airship passenger service from Los Angeles to Hawaii. His company completed another rigid airship blueprint on January 1, 1930, but ultimately nothing came of the project.

Knabenshue eventually ended up working for the National Park Service, where he promoted the use of autogiros to monitor forests. He retired in poverty, and had to plead for a meager pension. Still, he wasn’t entirely forgotten. In 1944, on the 40th anniversary of his Louisiana Purchase Exposition flights, Orville Wright sent him a telegram: “Don’t you remember it, and doesn’t it give you a thrill when you think of it?”

Knabenshue died on March 6, 1960. Among the five honorary pallbearers at his memorial service was Charles Willard.

Willard had gone on to a successful career in aviation and lived a long life, and was occasionally invited to aviation events. On October 1, 1956, during a ceremony placing a memorial plaque honoring him at Illinois’ Decatur Airport, he said: “We weren’t show people, and that was proven by the fact that we often lost money on our exhibitions. But that didn’t matter. Our sole object was to get the public aircraft minded.”

Emil Petrinic is an illustrator, designer, researcher and writer with a particular interest in early aviation and the history of lighter-than-air flight. For more about early exhibition flying and the interactions between Baldwin, Knabenshue, Willard, Curtiss and the Wright brothers, he suggests: Glenn Curtiss: Pioneer of Flight, by C.R. Roseberry, and The Wright Company: From Invention to Industry, by Edward J. Roach.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!