On July 10, 1969, I walked out of an administration building at Fort Myer in Arlington, Virginia. I had just finished the paperwork that processed me out of the Army. I was a civilian for the first time in two years. I felt damn good. I also felt very lucky.

On July 11, 1967, the day I was drafted into the Army, I felt a lot of things, but lucky was not one of them. As I slogged through eight weeks of basic training, the drill instructors rarely missed an opportunity to tell us draftees that we would be headed for infantry Advanced Individual Training at the notorious Fort Polk in the swamps of Louisiana, before going straight to Vietnam—where we’d be lucky to survive our first week.

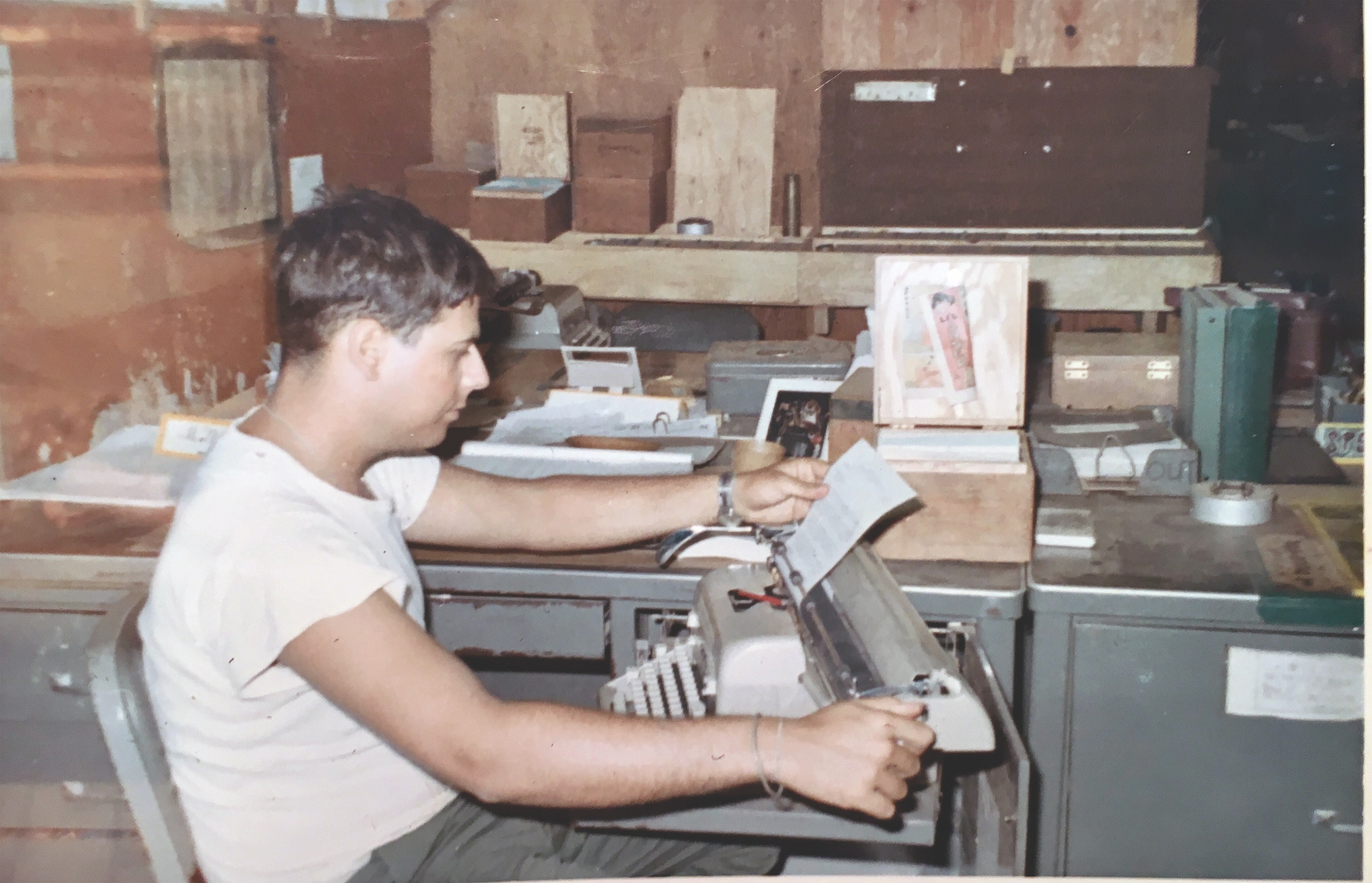

My good luck began after basic training when I received orders for clerk school. It continued after I arrived in Vietnam on Dec. 15, 1967. After four days at the giant Long Binh Replacement Station near Saigon I got orders to report to the 527th Personnel Service Company in Qui Nhon, a port on the coast of central South Vietnam—a safe area in the rear. After coming home from the war, I wound up with a great assignment: company clerk for an Army unit in Washington, D.C., where I went to college.

Other than thanking my lucky stars that I survived the war, I don’t recall reflecting much about my service in Vietnam that fine July day 50 years ago when I left the Army. I was just happy to be back in civilian life and have my military service in the rearview mirror. I took a temporary full-time job and then started graduate school. Life was good.

But not completely. Like nearly every other Vietnam veteran coming home to a bitterly divided country, I quickly figured out that hardly anyone wanted to hear about the war from those who had served in it. So I did what nearly all of us returning veterans did: I shut up about it and went about my business. I finished graduate school, got married, screwed around for a couple of years and then embarked on a writing career at age 28 in 1974.

It wasn’t until the late ’70s that I felt comfortable talking about the Vietnam War and my role in it. Well, mostly comfortable. Although I had mixed feelings about the war, I felt pride in having served my country. But I also felt that pride diminished by the sense that people who didn’t serve, and even some veterans, let it be known in subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) ways that my service as a rear-echelon soldier was inferior to that of “combat veterans.” To this day, I feel demeaned by the assumption that those of us who weren’t in combat units are some sort of second-class veterans. It’s as though there is a two-tier war veteran caste system, with former rear-echelon folks as the untouchables.

When people ask what I did in the Vietnam War, I tell them that I was drafted, then got lucky—that I was a clerk in a personnel company and that only one guy in my unit was killed the year I was there. Most people respond kindly and say, “You served. That’s a good thing.” Or words to that effect. That goes for nearly all of my fellow Vietnam veterans.

But—and it’s a significant “but”—I continue to hear “combat veteran” all the time. I admire and respect every Vietnam veteran who served in the combat arms. My feelings have nothing to do with their sterling service. But using “combat veteran” obliquely demeans the service of all of us clerks, cooks, truck drivers and other rear-echelon types. I realize that most people who use that term don’t intend to minimize or mock the wartime service of hundreds of thousands of other veterans, but that’s exactly what it does.

I was astonished to see British journalist Max Hastings go out of his way in his recent, big history of the war, Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy 1945-1975, to deride the service of anyone who wasn’t humping the boonies in Vietnam. How else to interpret this snarky, condescending sentence in which he sums up all rear echeloners’ war service:

“Maybe two-thirds of the men who came home calling themselves veterans—entitled to wear the medal and talk about their PTSD troubles—had been exposed to no greater risk than a man might incur from ill-judged sex or ‘bad shit’ drugs.”

Ken Burns’ much-ballyhooed 18-hour, 2017 Vietnam War documentary all but dismissed the service of men in noncombat units. The show offered hours and hours of grunts fighting but gave only a few minutes to rear-echelon people.

I understand that infantrymen could have negative feelings about us rear echeloners, but we were doing the jobs the military asked us to. And in Vietnam, contrary to Hastings’ ridiculous generalization, you were in danger no matter where you were. In addition to the GI killed in my unit while I was there—Stephen Allsopp, blown up on guard duty in 1968—three other men from the 527th Personnel Service Company lost their lives in Vietnam during the war. As did thousands of others not in the combat arms.

Although there are no official statistics, the best estimate is that 75 to 90 percent of those who served in Vietnam were in support units. That’s more than 2 million men and women who came home without the label “combat veteran.”

My suggestion to fellow veterans and those who never put on the uniform: Please consider dropping “combat veteran” from your vocabulary and replace it with “war veteran.” Or “Vietnam War veteran.” Or “Iraq War veteran” or “Afghanistan War veteran.”

While you’re at it, I wouldn’t mind a “thank you for your service.”

Marc Leepson is a journalist, historian and the author of nine books, most recently, Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Army Staff Sergeant Barry Sadler. He edited the Webster’s New World Dictionary of the Vietnam War and is arts editor, senior writer and columnist for The VVA Veteran, the magazine published by Vietnam Veterans of America.