.jpg)

Fighting on Strange Ground

Can poor planning and bad maps explain the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg?

In early June 1863, two Union topographical engineers spent several days studying the southern banks of the Rappahannock River with their field glasses, ascending repeatedly in a willow basket suspended from a gas-filled observation balloon. They were keeping close watch on General Robert E. Lee’s command, the Army of Northern Virginia, which was encamped along the river near Fredericksburg, Va. Only a month before, Lee’s Confederates had outwitted, outmaneuvered and overawed Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s Army of the Potomac at Chancellorsville, inflicting a harsh defeat on a numerically superior opponent and adding to the renown of the seemingly invincible Lee. President Abraham Lincoln resisted relieving “Fighting Joe” Hooker from command of the Army of the Potomac after that battle. Instead, he merely queried his chastened commander, “What next?”

Morning, noon and night, the airborne Union officers were keeping close watch on the scattered array of cooking fires. On the morning of June 4, the wood smoke that had wreathed the treetops and smothered the valleys was thinning. In its place, to the south and west, something else was in the air—dust, not smoke, which indicated an army on the move.

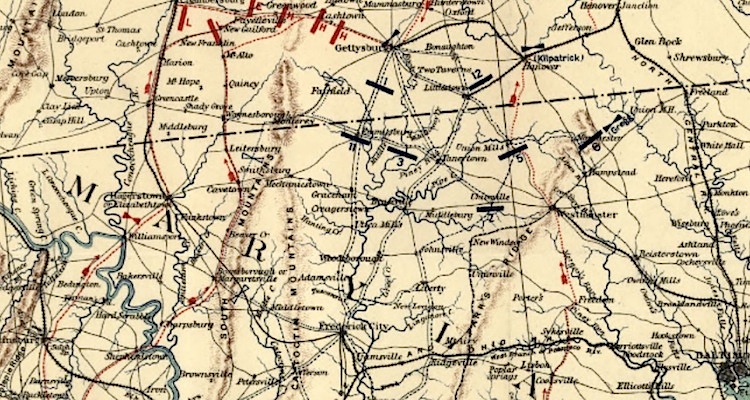

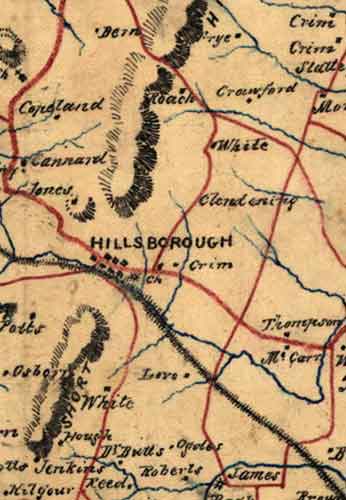

Months earlier, on February 23, Stonewall Jackson had asked his staff topographical engineer, Jedediah Hotchkiss, a civilian New Yorker-turned-Virginian, to prepare a theater map, a small-scale map that would encompass the entire region in which maneuvers might be carried on when the spring campaign season opened. The new map was to include the northern section of the Shenandoah Valley, northern Virginia, large parts of Maryland and south-central Pennsylvania. It was also to encompass the cities of Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington. The completed map would include well over 1,000 square miles of territory.

Hotchkiss’ first step was to locate his copy of a published map of Cumberland County, Pa. He also selected a 38-by-42-inch sheet of heavy watercolor paper and began to pencil in a grid that would eventually consist of thousands of square centimeters. Beginning a weeks-long process, he superimposed a similar pencil grid on the Cumberland County map so he could transcribe it, on a smaller scale, onto his own pencil-grid sheet. Over the next weeks, Hotchkiss followed the same procedure with other county maps.

This immense undertaking was still underway when Stonewall Jackson was mortally wounded in the fighting at Chancellorsville on May 2. The map meant for Jackson would become Robert E. Lee’s principal reference for his Gettysburg Campaign. As such, it provides an intriguing, and somewhat bewildering, glimpse into Lee’s haphazard preparations and how they fed into the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg.

Civil War–era armies were enormously vulnerable to the lay of the land and conditions on the ground. While individual soldiers could clamber up hillsides or breast their way across rivers, sizable units could not. The wheeled support vehicles on which a large army depended—cannons, caissons, wagons and ambulances—were completely road-bound. Nor could infantry advance in any significant numbers far beyond the cover of their artillery or the reach of supply wagons. The armies were attached at the hip to their wheeled vehicles, which were as dependent on passable roads as a train is to railroad tracks.

The Hotchkiss theater map was, in its own right, a wondrous production. Every rural resident’s name along the principal roadways, as well as the multitude of cultural features—mills, blacksmith shops and other establishments—appeared on the map. These names provided a general idea of an area’s population, and could help an army locate sufficient food, forage and water. But it was prepared in much too small a scale to inform a commander in the field, maneuvering a hungry, thirsty, enormous army that might be strung out for 50, 60 or 70 miles, advancing on multiple roads in unfriendly, unfamiliar territory.

The Hotchkiss theater map was, in its own right, a wondrous production. Every rural resident’s name along the principal roadways, as well as the multitude of cultural features—mills, blacksmith shops and other establishments—appeared on the map. These names provided a general idea of an area’s population, and could help an army locate sufficient food, forage and water. But it was prepared in much too small a scale to inform a commander in the field, maneuvering a hungry, thirsty, enormous army that might be strung out for 50, 60 or 70 miles, advancing on multiple roads in unfriendly, unfamiliar territory.

What the Hotchkiss theater map lacked were crucial features of the landscape. A small rise or a mild descent along the line of march could cause hours of delay. Horse- and mule-drawn vehicles could only manage with difficulty a 10-degree slope on a small hillock, and it was as hard for harnessed animals to descend a hill as to climb one. The Hotchkiss map showed only mountain ranges, and the name of a town could obscure a square mile or more of possibly critical ground. Woods, road surfaces, suitable fording sites, elevations, orchards and other necessary information did not appear at all. Relying solely on the theater map to march the Army of Northern Virginia through Pennsylvania would be like using a globe to get around Manhattan.

Lee was preparing to direct an immense army across a primitive road network in enemy territory that he knew little or nothing about. Securing adequate maps should have been a top priority at this juncture, a month before his jumping-off date. But in fact Lee did nothing of the sort. He detailed Jed Hotchkiss, the army’s preeminent mapmaker, to guide the ambulance carrying the mortally wounded Jackson to safety behind the lines.

When Hotchkiss returned, instead of requesting a map of his next campaign, Lee asked him to prepare an enormously detailed map of the Chancellorsville battlefield to accompany Lee’s report on the earlier battle. This report was a strictly bureaucratic detail that often was submitted months after a battle. Lee was exhibiting a strange sense of priorities. A long march by a large force into unfriendly territory was one of the most daunting military exercises of the day. Lee’s most important enemy at this point was the lay of the land.

Lee was distracted. He had spent much of the week of May 10 in Richmond, conferring with President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet and pushing his preference for an invasion of western Maryland and Pennsylvania. He also had to reorganize his army following the heavy casualties at Chancellorsville and the loss of Jackson. There were other problems related to Lee’s cavalry chief, the dashing Jeb Stuart, who was staging massive cavalry reviews, wearing out horses and men near Culpeper. Stuart then suffered a stinging setback when he and his men were caught napping by Union cavalry at Brandy Station on June 9. In short, in Virginia the logistical preparations for a major campaign were being overlooked in favor of other activities—some vital, some frivolous, some strategic, some personal, some superfluous.

Once Lee’s forces began crossing the Potomac River around Shepherdstown around June 19, the dearth of military map information began to show. Lee was no longer marching and fighting on familiar ground with the support of civilians. What’s more, some of the soldiers in his own ranks objected to a Confederate “invasion,” since they had enlisted to resist a Northern invasion. The Southland, after all, only ever wanted to be left alone.

Serious practical difficulties beset Lee’s army as well. His troops were unaccustomed to marching in a hostile environment. Men had to be detached to protect the wagon trains and escort couriers and messengers. The rear of the Rebel army could no longer be left to take care of itself, since Rebel stragglers might be captured, even killed. In this unfamiliar territory, orders had to be more precise at the same time that intelligence was less exact, harder to come by and impossible to corroborate. Troops were backtracking, countermarching, taking wrong roads and moving more cautiously—all of which tended to fatigue and frustrate soldiers and kept animals longer in harness and with less time to graze. Lee’s lack of good maps was already affecting his army’s performance on the march. Whether it would also affect its performance in battle remained to be seen.

Typically, cavalry provided guidance, protection and screening—to mask the intentions and movements of the army—on a campaign of this nature. They also gathered ground-to-saddle topographical intelligence. This last function, adequately performed, could have provided Lee with sufficient updated topographical data to annotate his small-scale maps. But Stuart, embarrassed by criticism about Brandy Station, had planned a grand gesture to avenge his honor and humiliate the Union army. He attempted to ride a circle around the Union forces, expecting to bring himself back on the right front of Lee’s forces as they moved into Pennsylvania. Instead Stuart rode himself and his best troopers completely out of the campaign. They spent days searching for the army they were supposed to be scouting for.

It’s fair to suppose that if Jackson had been leading his corps in this campaign, he would have had Jed Hotchkiss moving in advance of the army under a heavy escort of cavalry, reconnoitering and sketching as quickly as possible to fill in the topographical blanks for his commander. With his drawing board resting on the pommel of his saddle, Hotchkiss would have been investigating possible routes of march, locating water sources, evaluating fording sites and determining whether a mountain pass was negotiable. His cavalry escort would be riding down farm lanes and following bridle paths and wagon roads to get the names of inhabitants and determine whether trails led to parallel roads or perhaps fords. Distances and elevations on the sketch maps would be estimated using topographical shorthand.

The trot, canter and walk of a horse are so consistent that a skilled mapmaker like Hotchkiss would habitually keep count of his own horse’s steps. A typical scale on a sketch map might read “1,050 horse paces equal one mile.” Common objects could serve as visual frames of reference for estimating distances across larger expanses of ground: A church steeple, for example, was visible from 12 miles, while a single pane in a mullioned window could be distinguished at 500 yards. In between, familiar objects served as useful references, including grazing cows, fence posts, haystacks, telegraph poles, cornstalks. Road grades could be quickly determined by comparison with the level foundations of adjacent barns and farmhouses. In a panoramic vista, railroad tracks and rivers provided a level frame of reference for estimating the grade of the distant roads and hills.

The mapmaker would also note road surfaces. A macadamized road with its cobblestone-like surface could support army wagons with loads of up to 4,500 pounds, regardless of the weather. Wagons half that heavy would bog down on wet dirt roads.

Possible fording sites had to be assessed too. Men and cavalry could cross in much deeper water, but wagons filled with ammunition and supplies had to keep their beds dry, so crossing was feasible only where the water was less than 21⁄2 feet deep. Both banks of a stream had to be gentle inclines, and the stream bottom had to be firm and free of obstructions, so hundreds of wagons could cross without churning up an impassable mire.

Woods were an important feature, since roads usually narrowed through wooded regions, slowing the progress of a large force and making it difficult to deploy. Artillery was almost useless in wooded areas, which were particularly good places to ambush a marching force.

Another critical feature was elevations—hills, mountain ranges, mountain passes and gaps. Lee’s coup d’oeil, his ability to quickly grasp a terrain situation and turn it to military advantage, had worked well as he brought his force down the Shenandoah Valley. Hidden from Union forces by the Blue Ridge and South mountains, Lee had managed to hold the gaps and passes and kept Union cavalry from gauging the size and intentions of the Confederate march. But his lack of topographical intelligence caught up with him at Chambersburg, Pa. Of the nine wind and water gaps that punctuated the mountain barrier, Cashtown Gap, due east of Chambersburg, was the most strategically valuable. It was wide enough, straight enough and level enough to allow an army to pass. But Cashtown Gap was also wide enough for a Union Army to use in an attack on the Confederates. Were that to happen, Lee’s lines of communication and supply with Virginia would be broken and his freedom to maneuver would be lost. Lee had to keep his forces between the Union army and Cashtown Gap because the gap was his escape hatch. Gettysburg became a battlefield because it was on the road to Cashtown, not because Gettysburg was a transit hub, with roads radiating out like spokes from the town.

On June 28, however, the Rebel commander found himself stalled at Chambersburg, inquiring for the whereabouts of Stuart’s cavalry. Lee had a notion but no idea where the Army of the Potomac was. He was confident that Stuart’s continuing silence meant the Union forces must still be a safe distance away. Lee’s biographer, Douglas Southall Freeman, would later characterize the general as “a blinded giant.”

Lee spent his time at Chambersburg pondering various small-scale county maps that had been requisitioned, confiscated or captured, but their details were too skimpy to be of much use. He also questioned James Longstreet, A.P. Hill and Lafayette McLaws, trying to come to grips with the lay of the land. Lee would eventually dispatch eight couriers to look for Stuart. Eventually the information Lee had awaited from his cavalry commander—details that in Virginia would have been pouring in from civilians—was delivered by a scout, Henry T. Harrison, who was in the pay of James Longstreet. On June 28, Harrison told Longstreet and Lee the Federals were in strength near Frederick, Md., advancing in a wide arc toward Lee. The Army of the Potomac posed a much more immediate threat than Lee had thought possible.

Longstreet’s Corps was with Lee at Chambersburg, 25 miles from Gettysburg. Lee reluctantly sent orders to his widely dispersed forces to reunite near Gettysburg or Cashtown, eight miles to the west. Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell was with Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes’ Division at Carlisle, 50 miles north of Gettysburg, and Jubal Early began moving his division toward Gettysburg from York, 30 miles to the east. Third Corps commander A.P. Hill, already at Cashtown with Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s Division, ordered his other two divisions, under Maj. Gens. Dorsey Pender and Richard Anderson, to begin marching and join him in Cashtown.

Lee’s best mapmaker was accompanying Ewell, who had succeeded Jackson as commander of the Second Corps a month earlier. Ewell roused Hotchkiss in the middle of the night June 29 to draw a map and answer questions, presumably about the likeliest routes toward Cashtown and/or Gettysburg. The route they followed involved a march through a rugged pass to Papertown, Pa. In addition to Hotchkiss, topographical engineer Eugene Blackford accompanied Ewell on the march.

Thereafter, the battle at Gettysburg was poorly managed, if it was managed at all. The complex tactical plans Lee had in mind on July 2 were delayed, second-guessed, blindly adhered to, stretched to the limit or even ignored by his field commanders. Strangely enough, the hill known to posterity as Little Round Top, the centerpiece of the July 2 fighting, was initially completely overlooked by topographical engineers of both armies. A reconnaissance by Lee’s engineer, Captain S.R. Johnston, on the morning of the 2nd had, he insisted, carried him up the side of Little Round Top. Johnston reported seeing three or four Federal cavalrymen but no other Union forces nearby—which seems odd because that part of the field was actually swarming with Union troops at the time.

As the battle unfolded on the 2nd, Lee was almost entirely alone. British military observer Lt. Col. Arthur Fremantle looked on as the general sent just one message and received one report while the day and the battle went against him. If Lee had referred to Hotchkiss’ theater map before that day’s fighting, he would have seen that a good portion of the northern part of the field, the site of significant fighting, was completely obscured by the word “Gettysburg.” The 1858 Adams County map used by both commands named none of the now-famous landmarks—except the Sherfy Peach Orchard. Locating features like Seminary Ridge, Little Round Top or Devil’s Den wasn’t necessary on a county map.

No help was coming for Lee at that juncture. Roving Union cavalry under the command of Ulric Dahlgren had captured a lone Confederate messenger who was carrying an uncoded note from Jefferson Davis advising Lee that General P.G.T. Beauregard could not reinforce him—intelligence that may have influenced Maj. Gen. George Meade to remain in place and finish the battle. When Stuart’s command finally plodded into Gettysburg on the 2nd, some of his troops were led to the battlefield by their horses as the men slept in the saddle.

The most competently managed aspect of the Confederate invasion was the Rebel retreat, when the troops, retracing their steps, once again found themselves on familiar ground. But Ewell’s corps faced one last indignity: As they breasted their way across the swollen Potomac River at Williamsport, Md., on July 14, the muddy river bottom sucked 8,000 pairs of shoes from the soldiers’ feet. After a campaign initiated partly to gather supplies, and a battle partly brought on to secure footwear, many Rebels returned to Virginia barefoot.

One of Lee’s most fair-minded generals, E. Porter Alexander, summed up Gettysburg this way: “Not only was the selection of ground about as bad as possible, but there does not seem to have been any special thought given to the matter. It seems to have been allowed to select itself as if it were a matter of no consequence.” Lee’s Adjutant General Walter H. Taylor said, “Our men were worth twice as much south of the Potomac as they were north of it.” Using Taylor’s logic, the case can be made that Union troops were fighting at a numerical disadvantage whenever they confronted Confederates on Rebel turf.

Before the Gettysburg Campaign, Lee likely failed to recognize the enormous advantage he had enjoyed fighting on home turf, with the benefit of civilian support. It’s possible the Gettysburg “invasion” was simply too massive an operation for the Confederacy to mount. It may be too much to claim that inadequate mapping was a decisive factor. It was probably more like “windage”—the effects of wind that is just one of the factors a marksman has to take into account when aiming a rifle. Mapping was a factor that should have been taken into account before Gettysburg, but it was not.

Lee’s neglect of mapping may also highlight deep cultural differences between the warring sides. Commanders of the Army of Northern Virginia were celebrated for their audacity, élan and prickly individuality. But those qualities don’t guarantee the successful command of nearly 90,000 men and 5,000 wagons and cannons spread out for 75 miles on unfamiliar roads in hostile country.

Cartographer Earl B. McElfresh is author of Maps and Mapmakers of the Civil War. His most recent book is Marching With Maps & Mapping the Shenandoah Valley.