Engineer Railway Detachment 96446A braved blizzards and treacherous terrain while moving vital war materiel inland.

MOTHER NATURE stormed in at 50 degrees below zero, overwhelming the forces of Engineer Railway Detachment 96446A with the season’s first blizzard. The weather was “cold. Too cold. Too cold for men. Too cold for beasts. Too cold for steam locomotives, air brakes, steam valves and injectors,” wrote the unit’s commander, Major John E. Ausland, in his postwar memoir, Railway North to the Clouds. The railway was the White Pass & Yukon, a line that ran on 110 miles of rickety narrow-gauge track from the port of Skagway, Alaska, north to Whitehorse, in Canada’s Yukon Territory—employing a motley collection of cantankerous steam locomotives and tipsy rolling stock to move vital war materiel inland. When the temperature plummeted in mid-December 1942, Ausland’s railroaders were ill-equipped to fight the elements. They’d only been in Alaska for three months. Many were from America’s South and Southwest and had no notion that winter in the northern latitudes could descend so abruptly and brutally.

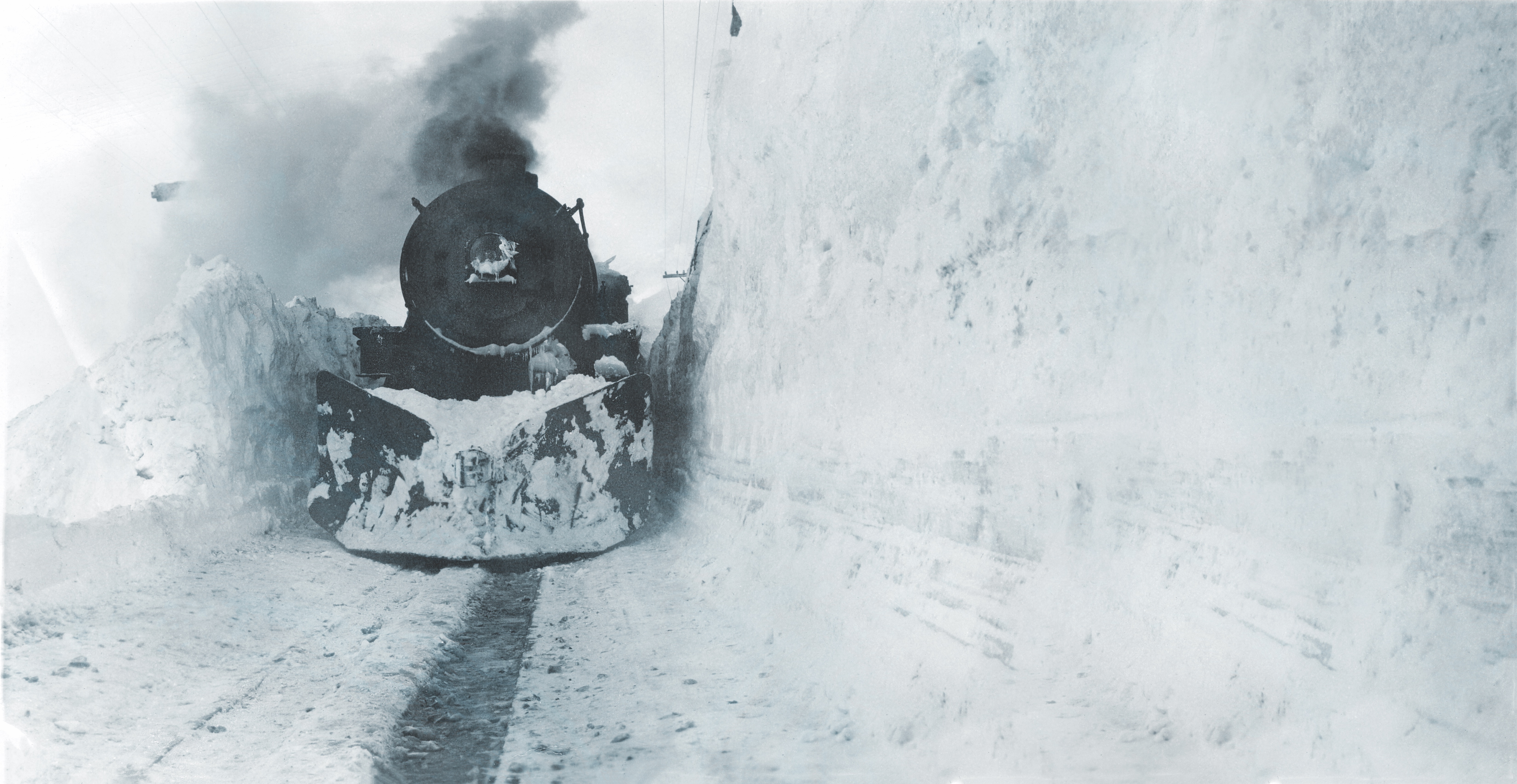

But the major’s orders from H.Q. in Seattle were explicit: “Run trains regardless of adverse weather conditions.” Ausland ruefully called them “instructions that could only have been written in a steam heated office a thousand miles south of us.” The army said that the trains must run, and so Ausland and his crews tried their damnedest to make that happen. But their adversary was unrelenting. The bitter cold fractured couplings and axles and fused wheels to the steel rails. Frostbite was endemic. Huge snowdrifts piled up in the passes, stopping powerful rotary plows in their tracks. When the weather moderated just before Christmas, the detachment’s G.I.s relaxed their guard, little suspecting that what they’d just been through was but a foretaste of battles to come.

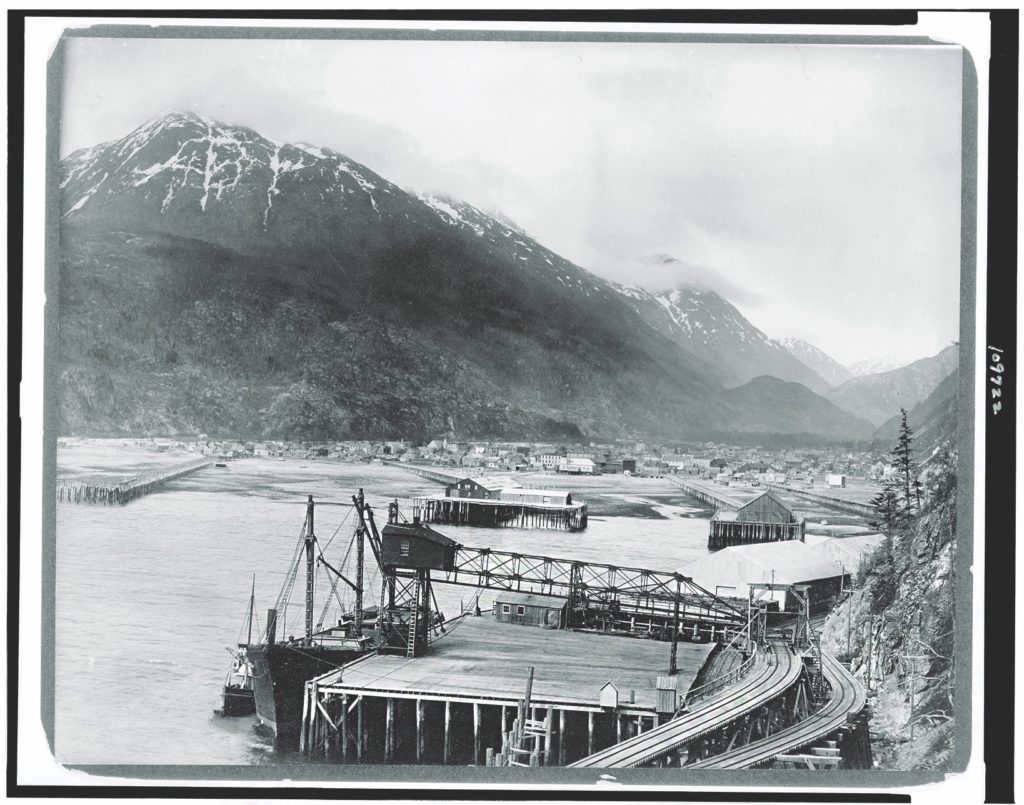

SKAGWAY HAD BEEN a quiet fishing village in the Alaskan panhandle until 1896, when gold was discovered in the Klondike—a 400-mile trek north over the treacherous Chilkoot Pass. This singular event attracted a flood of hopefuls and dreamers set on finding their fortunes in the goldfields. Within months, Skagway was overrun with 15,000 miners. As the rush ebbed four years later, the population fell to just a few hundred souls, and the town returned to somnambulance for the next four decades.

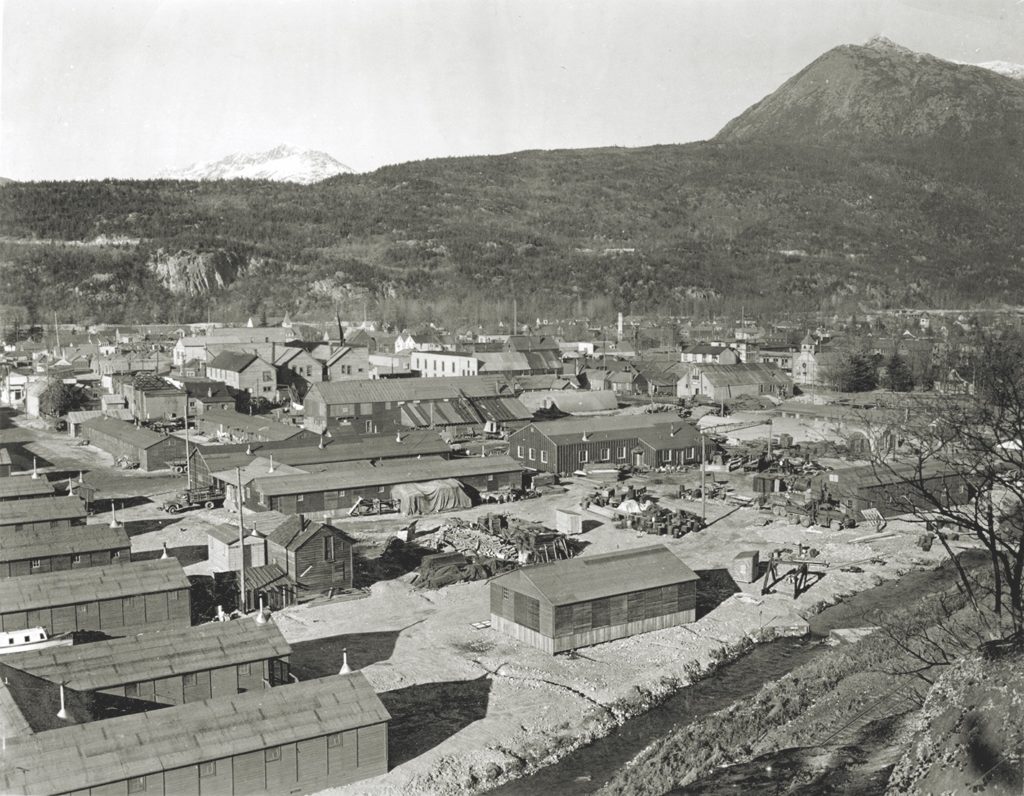

That all changed with the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, and received a further jolt in June 1942 when the Japanese invaded Attu and Kiska Islands in the Aleutian chain. Plans to build up defenses in Alaska Territory, ongoing fitfully since 1940, ramped up. Big projects on the drawing board included a dozen new airfields, an oil pipeline and refinery, and the Alaska-Canada (Alcan) highway, a 1,700-mile strategic link that would connect Dawson Creek, British Columbia, and Delta Junction, Alaska. The problem that confronted army planners was how to transport men and supplies into the vast roadless interior.

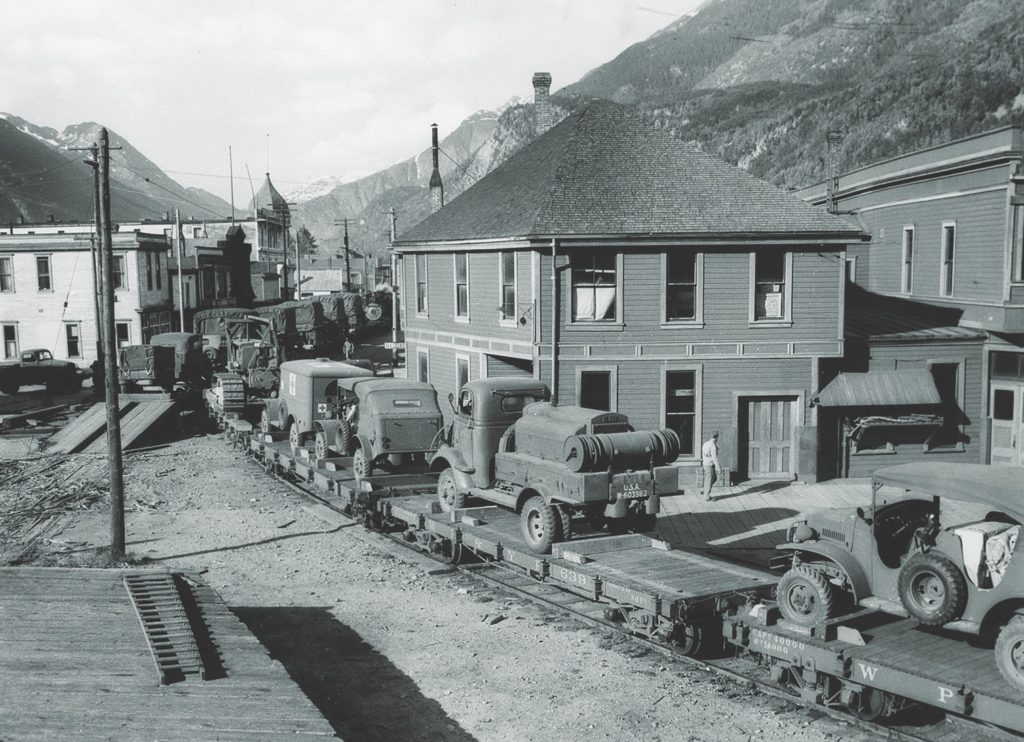

Skagway offered the solution: as the southern terminus of the White Pass & Yukon, cargo could be offloaded at the port on Taiya Inlet, at the northern end of the Inland Passage. It could then be moved by rail to Whitehorse to be distributed by paddlewheel steamers plying the Yukon River, a navigable waterway that crossed the entirety of central Alaska all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

When the line was completed in 1900 by a consortium of British bankers, Canadian contractors, and American engineers, the three-foot gauge railroad was considered an engineering marvel. Most lines in the country were “standard-gauge,” or 4 feet, 8½ inches between the rails; narrow-gauge lines were substantially cheaper to build, especially in rugged territory. Built through notoriously hostile—yet stunningly beautiful—country, the route was formidable. From sea level, the line climbed 2,900 feet in a scant 15 miles. The builders faced enormous challenges in carving a roadbed through granite mountains and bridging glacial torrents. At some points, the line clung precariously to dynamited ledges looming a thousand feet above the valley below.

The route through the mountain fastness was uninhabited, save for a few sourdough miners camped out along the way. It passed a manned maintenance station at Fraser, 28 miles up the line from the port, and the tiny villages of Bennett and Carcross, which was about two-thirds of the way to Whitehorse.

After Pearl Harbor, the little railroad did its best to move the U.S. Army’s voluminous cargo needs. But by late 1942, service employees had grown frustrated that crates of sorely needed supplies were piling up on the docks. To break the logjam, the government made an unusual deal with the owners: the United States would lease the entire railroad for the war’s duration, effective October 1, 1942. A survey conducted prior to the signing revealed its true condition—deplorable. It would take a prodigious effort to rehabilitate and operate the line. That’s where the Military Railway Service (MRS) came in.

The MRS traced its lineage back to the Civil War, when the Union army created a new command, U.S. Military Railroads, to run lines seized from the Confederates. To facilitate smooth operations, the outfit drafted experienced railroaders to manage the enterprise. During World War I, the army again turned to professionals to handle rail transport needs in France and Belgium. With the onset of World War II, rail operations became the responsibility of the newly formed U.S. Army Transportation Corps and, thus, the MRS. Organized along the lines of standard railroad divisions, the MRS created 42 operating battalions, many recruited by U.S. rail lines like the Burlington, the Great Northern, and the Santa Fe.

TWO WEEKS BEFORE the railway pact was signed, the ungainly named Engineer Railway Detachment 96446A—a hastily formed outfit of 360 seasoned MRS railroaders—arrived to take over the White Pass & Yukon line.

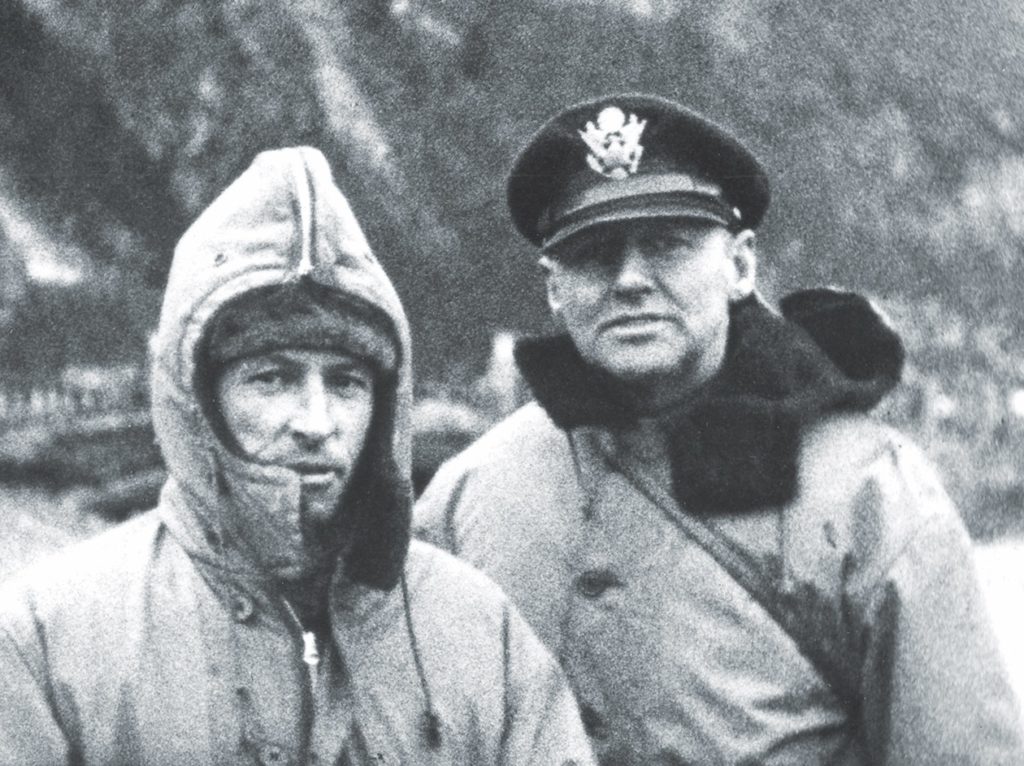

Detachment 96446A’s commander, Major Ausland, had been a superintendent on the Fort Worth and Denver Railway—a subsidiary of the Burlington system—in civilian life. Norwegian by birth and raised in Minnesota, blue-eyed Ausland, 46, was tall, fit, and spoke with a pronounced Upper Midwest accent. He also bore a common Nordic trait: he did not suffer fools gladly. After fighting in World War I with the Fifth Marines, he returned to the States to earn a master’s degree in railway engineering at the University of Illinois; he then took a job in the track department at the Burlington.

In 1940, with war clouds looming, Ausland joined the army reserve, and in July 1941, he was called up and immediately sent to Asia to oversee construction of a rail line from Rangoon to Lashio in northern Burma. When the Japanese overran the country in May 1942, Ausland evacuated via India and returned to the United States. In late August, he received a wire from MRS headquarters to take command of Detachment 96446A; he met up with his unit two weeks later on a Seattle pier as they boarded the steamer SS Princess Louise after orders had come for the outfit to ship out to Alaska.

Ausland’s men were newly inducted G.I.s, most of them with extensive and diverse railroading experience: engineers, firemen, shop mechanics, dispatchers, trackmen, conductors, and cooks, from 17 different railroads. Among them was Howard Foley, 32, from Queens, New York, and Guy Latham of Winslow, Arizona, 26, the lanky son of a cattleman. Foley, with his chiseled face and ruddy complexion, had been a switchman for the Long Island Railroad before joining the army in March 1941. Latham had worked as a bakery delivery driver until joining the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway in 1940. Though he didn’t possess as much experience as others in his company, Latham must have made a good impression on his superiors: he was designated engineer of #81, one of the largest locomotives on the White Pass & Yukon.

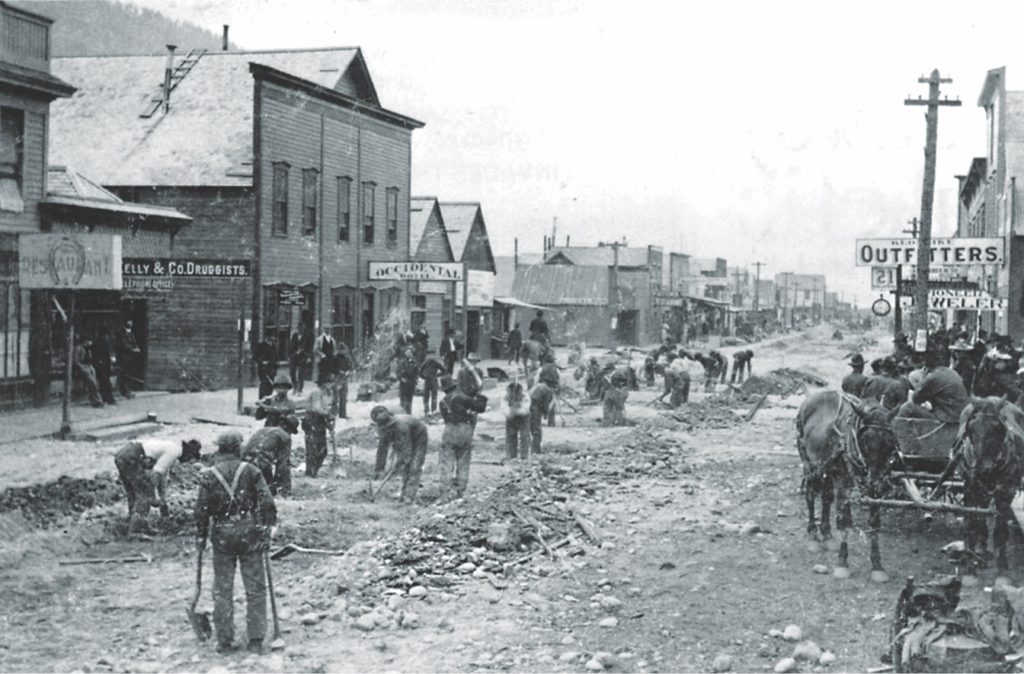

Skagway was not prepared to handle the influx of G.I.s. Empty buildings were requisitioned to house the headquarters and officers. The enlisted men made do with tents put up alongside the town’s muddy airfield. Even when equipped with wood-fired, potbellied stoves, their uninsulated six-man canvas shelters would prove useless against the approaching winter. After erecting their billets and converting an old hangar to a mess hall, the first order of business for the unit’s men was to familiarize themselves with all facets of the railroad. Maintenance crews from A Company diligently worked to rehabilitate the long-neglected right-of-way. The men from B Company began reconditioning rolling stock. Engine crews from C Company—including Guy Latham and Howard Foley—went out with local railroaders to learn the route’s intricacies. Many of White Pass & Yukon’s civilian staff—both American and Canadian—were retained to smooth the transition.

Major Ausland dealt with the myriad minutia inherent in establishing a new command. That meant grappling with U.S. Customs agents who, despite the exigencies of war, insisted upon exactitude on their voluminous federal forms, slowing the movement of goods in and out of Canada. He had run-ins regarding unloading priorities with the colonel leading the army stevedores at the port. He had run-ins with colonels from H.Q. in Whitehorse about how best to run his railroad. He had ongoing conflicts with his boss, Colonel Campbell C. McCullough—mainly about the chronic shortage of coal to fuel the engines. Their relationship was so frosty that one day in the mess hall, when Ausland greeted McCullough with a cheery “Good morning,” the colonel replied, “What the hell do you care?” On top of that, Ausland had to ride herd on his railroaders. When the only liquor store in town reopened after receiving a shipment of 10 tons of booze—the G.I.s called it “moose milk”—from the Lower 48, the queue into the sole spiritous shop snaked 10 blocks down the town’s main drag. Ausland ended up having to discipline several men for drinking on the job.

Under Major Ausland’s practiced superintendence, military railroad operations began in late September. Until then, the White Pass & Yukon had been running a single train a week, carrying barely 500 tons in good weather. In its first week, the unit shifted a total of 2,914 tons, employing 16 trains. It was an immediate improvement, but the army’s goal was to move 8,000 tons a week. Over the next two months, the average weekly tonnage crept up to nearly 3,500. That’s when the Yukon winter struck with a vengeance.

ON DECEMBER 11, 1942, the temperature at Skagway was a balmy 50 degrees. That night a cold front pushed in; by the 17th, at the height of the season’s first blizzard, the thermometer had plunged to 52 degrees below zero. Seasoned Yukoners told the Americans that when conditions got that bad, they’d just halt operations until things improved—a pause that could last days or even weeks. But orders were orders. The army said that the trains had to run. The command, now called the 770th Railway Operating Detachment, was unable to best the forces of nature. The line was shut down for five days, cutting the week’s carriage to just 98 tons—a deplorable performance in headquarters’ view.

In the storm’s aftermath, Ausland’s railroaders managed to move 1,042 tons in the first week of January 1943—well below November’s high of 3,720 tons, but the trend was steadily rising. It was then that the major’s run-ins with the colonels caught up with him and he was relieved of duty. It’s unclear whether Ausland’s superiors got fed up with his constant pushback or whether he had grown weary from all their interference. But having firmly planted the 770th in the wilds of Alaska, he left on January 29 after just five months of command. As he later wrote, “The men were showing so well the spirit I had tried to foster, and I was proud of them.” But he added, “I feel quite ashamed at having finally lost the Battle of Skagway.”

His replacement was Lieutenant Colonel William Paul Wilson, 48, another Burlington man with extensive experience in running trains. Illinois-born Wilson had a craggy, weather-beaten countenance that exuded calm and wisdom. He began his career as a teenage telegrapher and quickly moved up the ranks into railroad management. The 770th was his first military command.

Just as the new C.O. was settling in, Mother Nature again laid siege against the 770th: midday on February 4, 1943, the barometer at Whitehorse skidded downward. The next day, two feet of snow blanketed the tracks in many places.

The clash with the elemental forces began on the afternoon of February 6, pitting the 770th against a multi-pronged attack of snow, ice, and high winds along a 14-mile front between the stations at Glacier, 13 miles from Skagway, and Fraser in British Columbia. The army counterattacked with shovel-bearing troops and its fleet of snowplows, but the enemy’s resistance was tenacious.

The snow-clearing equipment used on the White Pass & Yukon wasn’t simple wedge-shaped plows but powerful steam-driven rotary snowblowers that spun a 10-foot diameter set of interlocking steel blades. These sliced through drifts and threw the detritus up to 100 feet away from the tracks. A veteran of many Minnesota winter campaigns, Wilson led the drive to clear the tracks using the southbound rotary train out of Whitehorse. Pushing the plow were two engines—one of them Sergeant Guy Latham’s #81. Switchman Foley rode in a rear car, alert for any trouble. The young railroaders had picked up valuable lessons during the December blizzard, but this ongoing storm would test their—and the 770th’s—mettle. A second rotary plow train was sent north from Skagway. The colonel’s plan was for the two units to meet up somewhere in the middle. But it was not to be. Not any time soon.

At 2:11 p.m. on the 6th, a vast drift stopped the northbound plow train dead in its tracks some 16 miles north of town, forcing it to retreat all the way back. The southbound plow train made more progress before its two engines derailed just below Fraser. While the crew of 23 soldiers tried to pull the steam engines back onto the tracks, the locos were kept alive by using old railroad ties as fuel and packed snow as boiler water. For the next three days, the storm swirled viciously around the 2,865-foot summit at White Pass and for miles beyond. Temperatures at Fraser of 30 degrees below zero, exacerbated by the “williwaws”—fierce gale-force winds blowing in from the Gulf of Alaska—brought the railroaders misery. “Men froze hands, feet, cheeks, noses, ears,” Wilson wrote.

The blizzard’s power increased on the next day, the 7th. The railroaders tried every trick in the book to rerail the engines, but their efforts were for naught. It wasn’t until late on the afternoon of February 8 that the southbound rotary, back on track, finally broke free from nature’s clutches. It reversed a mile to the coaling bunker at Fraser, where a small supply awaited. Down the line, the northbound rotary, on a second attempt at clearing the track, made good progress, nearly reaching the summit at White Pass. But suddenly, the bitter cold fractured the drawbar that coupled the lead engine to the plow. Wilson ordered the enginemen to “kill” their engines for lack of fuel by letting their fires go out. Now nothing moved on the White Pass & Yukon.

As Colonel Wilson noted in his report, the “situation at Fraser [is] beginning to look serious.” That was an understatement; the crew was marooned. The 23 men took refuge in a small shed built to bunk just six track workers; they “piled in there like cordwood,” as Wilson put it. To make matters worse, rations were running out. Fortunately, the telegraph line still worked, so the colonel sent a wire up to Carcross, 40 miles to the north, where civilian contractors were laying an oil pipeline. They sent a Caterpillar D4 tractor pulling a sled loaded with fuel and supplies down to the southbound rotary at Fraser. After crossing an ice-bound lake and stalling for hours in a snowdrift, the big Cat reached Wilson’s refuge at 6 p.m. on the 10th—appearing, according to the C.O., like “six regiments with colors flying.” The load included four tons of coal and a substantial amount of food. Famished as they were, Guy Latham later recalled that the G.I.s’ first impulse was to rush for the cartons of cigarettes.

Over the next 24 hours, the Cat made three more coal runs from Carcross to Fraser, bringing in a total of 18 tons. And by the early evening of February 11, the southbound rotary, fully fueled and watered, was finally able to clear the line at Fraser and begin working down toward the U.S. border at White Pass, eight miles distant. It was slow going, but to everyone’s relief, the weather was starting to improve. On the 11th, the low was a mere 6 degrees below zero and the winds had moderated. The northbound rotary had dug itself out, too, and it began its trek north, reaching Glacier the next day. On the 13th, both plow trains met near Inspiration Point, 17 miles north of Skagway. Colonel Wilson’s report entry for the 14th, Valentine’s Day, says simply, clearly, and emphatically: “REST.”

FOR 10 DAYS, NATURE HAD repulsed the U.S. Army’s every effort to clear the line until, on February 15, the 770th claimed victory as its relentless adversary retreated and the line finally reopened.

In the spring and summer of 1943, the 770th went on to hit its goals and then some, averaging over 10,000 tons a week in up to 34 trains a day. The next winter brought another tempest that closed the White Pass & Yukon for 15 days in March 1944 and made newspaper headlines across the U.S. and Canada. The main cargo during this period comprised bits and pieces for the Canol project—a 400-mile pipeline from oil fields in the Northwest Territories to Whitehorse—and a recycled oil refinery shipped in sections from Texas. When completed, the army would be able to supply its growing network of airfields with fuel that didn’t have to be shipped up from the Lower 48.

Their Alaskan mission accomplished in late 1944, the 770th Railway Operating Detachment went on to help rebuild railroads in the Philippines and Korea. The command was disbanded in 1946, and most of its railway men returned to work on the lines they had left upon enlisting.

Although they never faced live enemy fire, the men of the 770th regularly battled Mother Nature to ensure the delivery of strategic war materiel—564,446 tons of it in all. And those battles left a lasting impression: Howard Foley, the switchman from the Long Island Railroad, may have best summed up the 770th’s White Pass & Yukon experience when he told a reporter in 1943, “That line is too steep for a goat and too cold for a polar bear.” ✯

This article was published in the February 2021 issue of World War II.