A band of daring fliers team up in a classified program to take out the radars guiding their biggest threat—Soviet SA-2 Guideline missiles.

Like many American boys who had grown up during World War II, Stan Goldstein was fascinated with aviation. He began flying at age 12 and entered Air Force ROTC at New York University while earning an engineering degree. After graduating in 1956 he wanted to serve his country and fly, but his 20/50 eyesight prevented him from becoming a pilot. So Goldstein chose navigator training and went off to Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, for preflight, then farther south to Harlingen for nav school.

Before the development of Inertial Navigation Systems (not to mention the satellite-based Global Positioning System), a navigator could make or break a mission. Flying around Texas in a T-29C, a navigator trainer, Goldstein learned to use basic grid references and LORAN (a long-range navigation radio system). He also became adept at celestial navigation. Most navigators were sent off to feed the Strategic Air Command’s insatiable appetite for fresh meat to fill deployment schedules and nuclear alert commitments, but Goldstein volunteered to become an electronic warfare officer.

At that time EWOs were still an oddity and their mission largely misunderstood. Assigned to fly aircraft crammed with temperamental, rudimentary equipment, an EWO was a long way from the sexy aviator image; Goldstein said that a tactical electronic warfare officer on a plane was as ugly and redundant as “a wart on a frog.” But electronic combat became a high priority for the United States with the proliferation of radar-guided threats such as the S-75 Dvina (NATO code name: SA-2 Guideline) surface-to-air missiles, or SAMs.

On July 24, 1965, Soviet advisers to North Vietnam had launched an SA-2, blowing an American F-4 Phantom out of the sky near Hanoi, the first of several U.S. kills using this fearsome new technology. Pentagon officials were stunned by the SA-2’s effectiveness against fighter aircraft. Fighters carried no warning or self-protection equipment at the time, and even if they had, no one really knew how to outmaneuver a SAM in 1965.

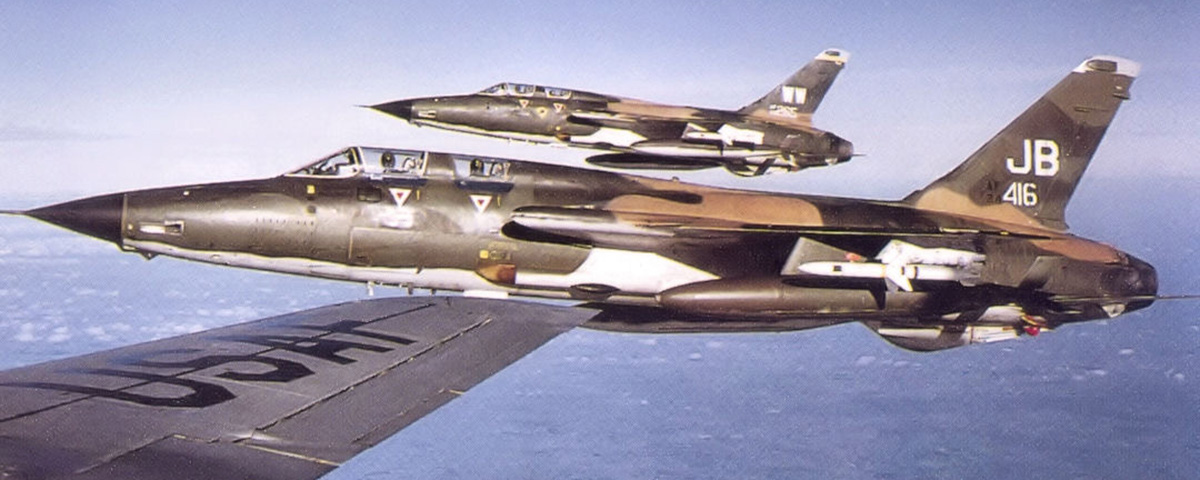

To counter this new weaponry, officials created a classified program to develop dedicated SAM detection and suppression aircraft as an electronic combat solution. “Project Wild Weasel” started in the summer of 1965 and formally went into effect in August. Over the next two years, the Air Force and Navy tested aircraft platforms outfitted with radar-seeking missiles, relying on volunteer crews. The F-105F, a two-seater, was converted for the role in 1966 and was designated “Wild Weasel III.”

Arriving in October 1967 at Nellis Air Force Base in Texas as part of the Wild Weasel III phase, Goldstein, seven other EWOs and eight pilots would learn to fly and fight in the F-105F. Assigned to the 4535th Fighter Weapons Squadron, Goldstein learned about the threat systems they’d face, tactics, countertactics and the specialized equipment on the Weasel.

The EWOs and pilots would learn about each other as well, when they paired up to fly the two-seater. Goldstein, who had risen in rank to major, met Major John Revak, a fighter pilot with seven years’ experience. Revak had flown the F-105D Thunderchief, or “Thud,” with the 23rd Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS) in Germany and was eager to get to the action in Southeast Asia. “Revak and I were a natural fit,” Goldstein recalls. “We were both bachelors and had grown up in New York City. He was calm and somewhat more reserved, which balanced my more boisterous approach to life.”

Goldstein paid close attention to his instructors, since casualty rates over Vietnam were higher than 50 percent for Wild Weasels. During Operation Rolling Thunder, the U.S. bombing campaign against targets in North Vietnam, more than 2,500 SAMs had been fired at Americans since 1965, and at least 105 aircraft had been lost to the SA-2. Since the Weasels had been flying, however, it was taking more and more SAMs to bring down U.S. combat aircraft—17 per jet in 1966 went up to 32 per jet in 1967.

The EWO students had never been in fighters before and needed to be fitted with G-suits, which fliers called their “speed jeans.” The EWOs began flying in the T-39F Sabreliner to become familiar with APR-25/26 and ER-142 panoramic receivers, electronic countermeasure sensors that detected enemy radar signals. The co-pilot’s console had been removed and the F-105 R-14 radar installed in its place. Typically, students would fly four or five T-39 flights, and about 22 sorties in the F-105F. Goldstein and Revak were due to graduate on Feb. 5, 1968, but on January 26 they received sudden orders for Korea. Three days earlier, the USS Pueblo, a former cargo ship converted to gather intelligence, had been attacked and captured by four Communist torpedo boats, two sub chasers and a pair of MiGs. In response to the Pueblo crisis, all 16 students were being sent to Korea in preparation for a second Korean War.

One of the great strengths of the U.S. military is its ability to dedicate a tremendous amount of talent, funding and creativity to a given problem. Despite initially neglecting the field of electronic warfare, the Americans by 1968 had made significant advances in response to their combat losses from SA-2s guided by fire-control, tracking and fire-director radars that NATO called Fan Song and Fire Can. Fan Song was a trailer-mounted E band/F band and G band fire-control and tracking radar used with the SA-2 surface-to-air missile system. Fire Can was a type of Soviet fire-director radar, also known as SON-9, used to direct 57mm and 100mm anti-aircraft guns.

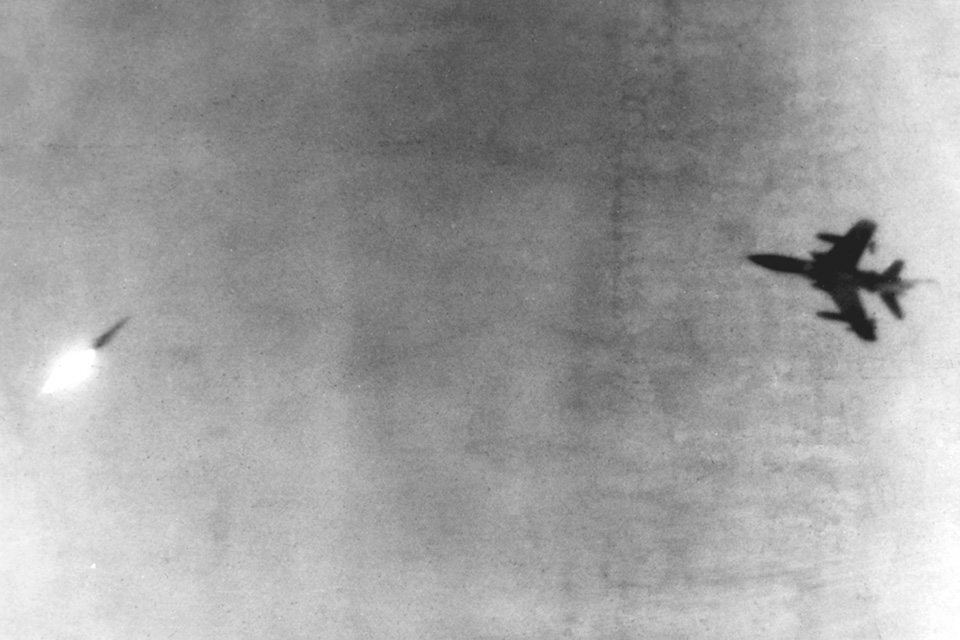

In addition to electronic countermeasures, anti-radiation missile technology, or ARM, was evolving as a more active response to the threat of improved Soviet radar. First fired in combat on April 18, 1966, near Dong Hai, about 40 miles north of the Demilitarized Zone, the AGM-45 Shrike, an American anti-radiation missile designed to home in on hostile anti-aircraft radar, proved less than optimal: For the next three months, 107 Shrikes loosed at enemy emitters in North Vietnam resulted in a single confirmed hit. With 116 aircraft losses to SA-2s between July 1965 and February 1968, the U.S. military had to find a better solution. It focused on developing the AGM-78 Standard Anti-Radiation Missile, or STARM.

Like the Shrike, the STARM was initially a Navy project that mandated off-the-shelf technology, in this case the RIM-66A/B surface-to-surface missile. Designed to target ships, it was big, at 15 feet long and 1,400 pounds. Over 210 pounds of that was a blast fragmentation warhead, a vast improvement from the Shrike’s puny 149-pounder. Because of its larger rocket motor and better seeker head, the STARM could potentially be employed 50 miles from the target, giving it a longer range than the SA-2. For the first time, American fighters could attack without venturing into anti-aircraft gun range.

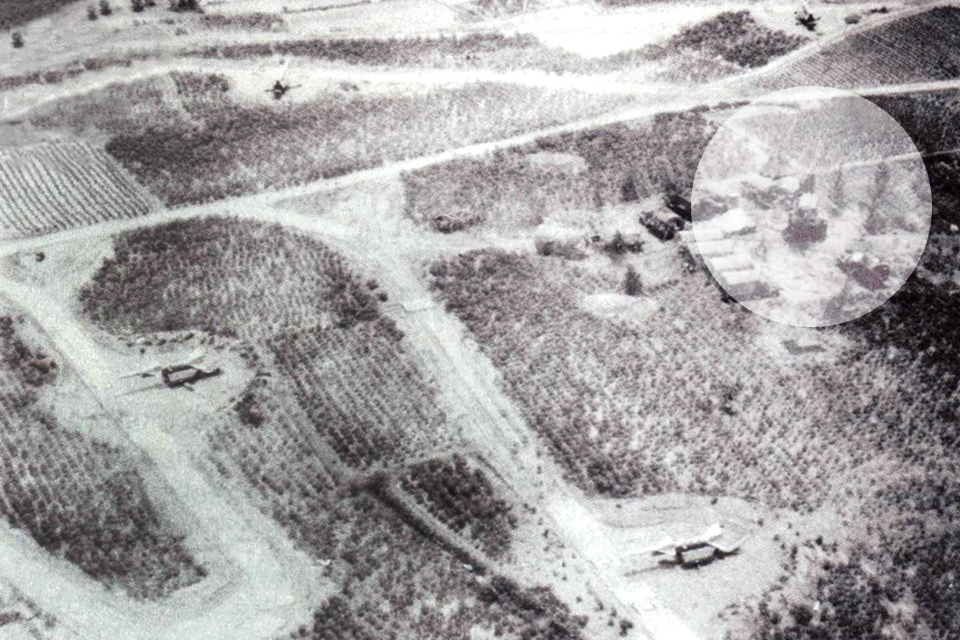

The Air Force first used the new anti-radiation missile in Vietnam on March 10, 1968. In the predawn hours, four Weasels from the 357th TFS , the Lickin’ Dragons, took off from Takhli Air Base in Thailand. Their mission: Cover 16 F-4D Phantoms hitting a target near Hanoi. Each of the four F-105Fs in the escort “Barracuda flight” carried a single QRC-160-1-8 improved electronic countermeasure pod on the left outboard wing station, a 650-gallon fuel tank on the centerline and two AGM-78A STARM missiles on both inboard stations. These were Mod 0 missiles still in development, not production versions, and they carried the same T1 seeker head found in the Shrike.

The Weasels had picked up early warning radar emissions 100 miles from the target; missiles and guns were certain to be waiting. Unfortunately for the raiders, broken cloud decks extending up to 12,000 feet and mechanical issues forced half of the Phantoms to turn back, but eight, including the four in Barracuda, pressed on to the Hanoi suburbs where the striker target was.

Shortly before the 0600 time over target, Barracuda went into a racetrack cap, an elongated orbit, 20 miles from the closest Fan Song, right at the fringe of its engagement envelope. Six SA-2s launched. The anti-aircraft radars were up as well, and 85 to 100mm guns opened up. The four Weasels fired all eight STARMs at valid Fan Song radar signals. Two of them exploded a few miles after launch; it was later determined that their rocket motors had been damaged in transit, so that when the STARMs made their 5-G pitch up, the cracked motor casing came apart and the propellant exploded. A third STARM didn’t function because the arming lanyard had been inadvertently left off by the ground crew.

The five remaining missiles functioned properly and disappeared through the clouds toward the radars. Two had no measurable effect, either on signals from the ground or on missiles in flight. Three did. Several SA-2s went ballistic very soon after the STARMs’ impacts. The STARMs may have hit the radar or impacted close enough to damage it or caused the Fan Song operators to shut down simply as a result of their launch. Whatever the explanation, none of the SAMs found their marks, no Weasels or Phantoms were lost and the target was successfully destroyed.

The 37 percent success rate for the first combat STARM employment wasn’t matched by subsequent missions, which held at around 20 percent, but the STARM was better than the Shrike.

Anti-radiation missiles only functioned if the enemy radar cooperated by continuing to transmit. If a Fan Song or Fire Can blinked off temporarily, or shut down altogether, the pursuing Shrike simply went stupid and stuck itself in the earth somewhere. Later-model STARMs made some provision for this by incorporating a memory circuit, and if the radar signal vanished, the missile would guide itself to the approximate last known location and detonate.

The North Vietnamese quickly improved their counter-tactics, consistently practicing emissions control, or limiting radar transmission times. With very short on-air times, a SAM radar would emit long enough to launch a missile, guide it to intercept, then shut down. Such a tactic usually prevented a Fan Song from being located, and even if it was, there would rarely be enough time to use that location information to guide the STARM to the target. Cooperative feed tactics were also used: Fire Cans and early warning radars provided rough target information to the Fan Song. The target-tracking radar operators would stand by and then come on-air just long enough to acquire the target and guide the missile. Spare radar units were on-site whenever possible and ready to replace any that were damaged or destroyed.

Assessing the damage to radar was ambiguous at best. The effectiveness of conventional weapons like bombs, guided rockets and kinetic missiles is measured according to a “probability of kill,” referred to as a Pk or K-kill. That calculation estimates the number of weapons of any given type it will take to irreparably damage a target. The value changes based on the weapon employed and the type of target. Anti-radiation missiles were not designed to kill radars, but rather to damage them; therefore, a “probability of hit” estimate (sometimes referred to as “probability of success”) was used instead of a Pk.

None of this is to say that anti-radiation missiles were wholly ineffective. In fact, the threat of Shrikes and STARMs actually counted for more than the missiles themselves. If the North Vietnamese could be forced into degraded modes of operation or forced to shut down with missiles in flight, then anti-radiation missiles were partially successful, much as MiGs were considered successful if they could force American fighters to jettison their bomb loads before attacking, whether they shot any down or not.

North Vietnamese air defense regiments scrambled to meet the adaptive U.S. threat, employing variously effective means. In late fall 1967 the North Vietnamese 236th Missile Regiment modified its Fan Song engagement sequence by switching to “three-point guidance.” The normal automatic mode was used to launch the radar, but the operator would switch to manual control once the missile was safely airborne and tracking its target. With a few seconds remaining to interception, the operator would switch back to auto mode. This abrupt change in guidance signals allowed combat under heavy U.S. jamming and sometimes neutralized the Americans’ APR-25/ER-142 receivers.

Yet interfering with Fan Song or Fire Can radars was only part of the solution to the SAM problem. From the beginning of the Vietnam War, both the military and the CIA had made numerous attempts to intercept the SA-2 uplink signal. These guidance commands were transmitted to a beacon transponder on the rear of the missile, which would then reply and establish two-way communication. If that coded reply could be acquired and dissected, then a program could be created to jam it.

Research on ways to beat the radars indicated that specialized pod formations, optimized for electronic coverage, would be most effective. Takhli’s 355th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW) flew in four ships spaced about 1,000 feet apart, with an altitude stack of 750 feet from top to bottom. The 388th TFW at Korat Air Base in Thailand flew a bit wider, with 1,500 feet between jets and a deeper top-to-bottom stack of nearly 2,000 feet. This initially played havoc with the SAMs, causing launched missiles to lose control and crash. In 1967 the SAM kill rate against U.S. aircraft utilizing pods fell to 16 percent, down from 50 percent in 1966.

But when their radar screens became cluttered and unusable, the North Vietnamese began tracking the jamming source itself. Those tight pod formations created a fairly defined noise strobe, so an accurate azimuth to the jammer source was easy to see. Establishing range was trickier, but by using geographically separated Fan Songs, Fire Cans and other radars, the triangulation calculation could be made and then passed by landline to the launching SAM battery.

During a three-day period at the end of November 1967, eight Air Force jets were lost to the SAMs: one F-105F, two RF-4C reconnaissance Phantoms and five F-105Ds. Neither the Weasel nor the reconnaissance jets used pods because jamming interfered with their own equipment. But striker Thuds all flew tight, nonmaneuvering pod formations to maximize jamming effectiveness. Following an investigation, the tactic of close formations over enemy territory was discarded almost immediately.

On March 25, 1968, now flying with the 44th Tactical Fighter Squadron, the Vampires, 388th TFW, out of Korat, Majors Goldstein and Revak prepared for their first Weasel mission over North Vietnam. Six days later, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced that, in addition to not seeking re-election, he was curtailing bombing north of the 19th parallel in North Vietnam in hopes of negotiating a peace with Hanoi. Effective April 1, strike and Weasel missions would be restricted to the southern wedge of North Vietnam between the Demilitarized Zone and Vinh: roughly Route Packs One and Two.

Launching at 0720 on the 25th, Goldstein and Revak flew with the Vampires into Pack One, supporting an Arc Light missile strike against the Mu Gia Pass. If the passes into Laos and South Vietnam could be closed down, the White House reasoned, then the war in the South could be throttled. For Goldstein and Revak, it didn’t much matter. Air Force policy specified that a Vietnam tour ended after one year in-country or 100 missions over North Vietnam; with their first mission completed, they had only 99 more to go.

The rapid development of weapons and systems to fight the SAMs slowed considerably following the April 1 bombing pause. Just as operations and tactics had been modified for Rolling Thunder missions, they would have to be adapted for combat in the southernmost route packs and along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Meanwhile, Hanoi used the new bombing restrictions to begin widespread repairs and reconstruction of roads, bridges, depots and railways. Without fear of American air attacks, the North Vietnamese Army could move far south by rail, and arms, ammunition and supplies were stockpiled in depots a mere 20 miles north of the DMZ. In Route Pack Two, the air base at Vinh was back in service, while another was built far to the south near Dong Hoi. SAMs moved south as well, and by late spring there were four units below the 19th parallel. Spare parts and extra missiles also had to travel some 250 miles farther south; as a result, SAMs only fired when they had a high-value target—or if they were deliberately provoked, hunted and attacked.

That’s what the Weasels did.

In May 1968 the F-105Fs made 26 attacks on SAMs south of the 19th parallel. This increased to 38 in June and 82 in August. Some of these “hunter-killer” missions were planned in conjunction with other missions, but after a primary target was hit, the Weasels would often go trolling for SAMs—usually in the “shoot me” altitude blocks above 6,000 feet.

Purposely easy to see on radar, the Weasels would zoom back and forth close to suspected SA-2 sites to see if they could provoke a Fan Song or Fire Can radar to stay on long enough to locate it and attack. Sometimes it worked, and sometimes it didn’t. On July 15, 1968, the 44th TFS lost its first Weasel since February to 37mm anti-aircraft fire over a SAM site, and on September 30 the 333 TFS from Takhli lost another one over the same site.

At Korat, Goldstein and Revak were closing in on their long-awaited 100th mission over North Vietnam when the president made another announcement that would affect Weasel missions. On Oct. 31, 1968, Johnson said that in light of the developing Paris peace talks, he was ordering all air, naval and artillery bombardment of North Vietnam to cease as of 8 a.m., Washington time, the following morning. For the pair of fliers, this could be the difference between going home in a few weeks or having to wait until their year was up in March 1969.

On November 25 Goldstein and Revak were patrolling on the Laotian side of the border, covering the passes through the Annam highlands, when emergency beacon signals started blaring. Grommet Two, an F-4D escort for an RF-4C photoreconnaissance jet, had been hit by anti-aircraft fire near the Ban Karai Pass into the North Vietnamese-Laotian border region.

All airborne missions stopped when someone went down, and nothing had higher priority than the recovery effort. Helicopters and attack planes were cleared into the working area while the two Weasels trolled for missile threats.

Searching electronically for radars and SAMs, Goldstein and Revak strained their eyes trying to spot airbursts or missile trails. Grommet Two’s pilot and the EWO had ejected safely within a half-mile of a North Vietnamese encampment and were talking to the A-1 Skyraiders, but as a Sikorsky MH-53 helicopter approached to pick up the fliers, the surrounding hillsides erupted with small-arms fire.

Goldstein and Revak did what they could to help save Grommet Two. They trolled for SAMs, acting as bait to keep the rescue aircraft safe, but no SAMs targeted them. They faced only anti-aircraft guns. Caught up in the rescue attempt, it wasn’t until later that both men realized they had actually been across the North Vietnamese border and back for the 100th time. As they clambered off the ladder at Korat, they received the traditional hosing off and accolades for surviving warriors. In December Goldstein and Revak headed for home.

Operation Rolling Thunder was over. Between March 1965 and November 1968, some 864,000 tons of bombs were dropped on the North, more tonnage than was employed in the entire Korean War. A total of 306,183 combat sorties were flown by U.S. aircraft—153,784 by the Air Force. The bombing did not force Hanoi to negotiate, nor did it destroy the Ho Chi Minh Trail, though it did severely curtail operations.

A CIA analysis reported $6.60 spent for each dollar’s worth of damage to North Vietnam. Operational and combat aircraft losses totaled 506 from the Air Force and an additional 416 lost from the Navy and Marines. More than 450 naval aviators were killed, wounded or captured. The Air Force lost 255 killed; 222 captured, including 23 who died in captivity; and 123 missing in action.

In the end political restrictions, diplomatic compromises and a divided U.S. command structure marginalized the success of Rolling Thunder. Those culpable, both in and out of uniform, put true victory out of the hands of those who fought so skillfully and sacrificed so much.

Vietnam’s Wild Weasels is adapted from The Hunter Killers: The Extraordinary Story of the First Wild Weasels, the Band of Maverick Aviators Who Flew the Most Dangerous Missions of the Vietnam War, by Dan Hampton. Copyright 2015 Ascalon LLC. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Vietnam’s Wild Weasels is adapted from The Hunter Killers: The Extraordinary Story of the First Wild Weasels, the Band of Maverick Aviators Who Flew the Most Dangerous Missions of the Vietnam War, by Dan Hampton. Copyright 2015 Ascalon LLC. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Dan Hampton, a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel, flew 151 combat missions in the Gulf War and Iraq War. He is a graduate of the Air Force Fighter Weapons School, Navy Top Gun School and Texas A&M University. The Hunter Killers is his third book.

Vietnam’s Wild Weasels originally appeared in the August 2015 issue of Vietnam. Subscribe here!