For one tribal leader, the decision to make war on the United States was a matter of rights and spirituality. In the 1850s, Victorio emerged as chief of the Chihenne, one of four bands of the Chiricahua Apache tribe in southwestern New Mexico. The Chihenne laid claim to the Warm Springs, known as Ojo Caliente in Spanish. The other Apache bands—one of them headed by Geronimo—ranged to the west, in southeastern Arizona and northern Mexico. Victorio profoundly believed that Ussen, the reigning deity of Apache cosmology, had created the Warm Springs especially for the Warm Springs people. This was their place of origin, their source of tribal strength. Ussen had commanded them to live there and care for it. But the United States government insisted on making that impossible.

For one tribal leader, the decision to make war on the United States was a matter of rights and spirituality. In the 1850s, Victorio emerged as chief of the Chihenne, one of four bands of the Chiricahua Apache tribe in southwestern New Mexico. The Chihenne laid claim to the Warm Springs, known as Ojo Caliente in Spanish. The other Apache bands—one of them headed by Geronimo—ranged to the west, in southeastern Arizona and northern Mexico. Victorio profoundly believed that Ussen, the reigning deity of Apache cosmology, had created the Warm Springs especially for the Warm Springs people. This was their place of origin, their source of tribal strength. Ussen had commanded them to live there and care for it. But the United States government insisted on making that impossible.

The Chihennes knew every rocky height and sinuous crevice of the tangled land, and they knew how to position themselves on craggy elevations ideal for ambushes.

No western American Indian chief received shabbier treatment from the U.S. government than Victorio. No one had greater cause for launching a war against his oppressors. And no one demonstrated a greater mastery of guerrilla warfare. As one veteran officer summed up, Victorio was the “greatest Indian general who had ever appeared on the American continent.”

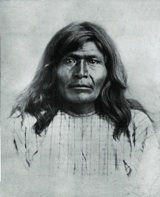

Born in the early 1820s, Victorio rose to warrior status through the intense training that shaped all Apache fighters. Short and muscular, he impressed white negotiators as sincere and soft-spoken. And while some saw in his face the merciless savage, others thought he had an agreeable countenance.

His home, Warm Springs, is nestled between the craggy, forested Black Range of the Mimbres Mountains to the south and the San Mateo Mountains to the north. The Mimbres range extends north to south about fifty miles west of the Rio Grande (in New Mexico, the river runs north to south before turning southeast at El Paso). The springs give rise to Alamosa Creek. Shadowed by the San Mateo Mountains and spurs of the Black Range, the creek flows southeast into the Rio Grande. The Chihennes relied chiefly on raiding into Mexico for subsistence, stock, and trade goods. A small Mexican village sprang up in the valley about thirty miles upstream from the Rio Grande (near modern Dusty), and there the Indians traded their plunder for arms, ammunition, and whiskey.

In the 1850s and 1860s, agents sympathetic to the Chihennes tried in vain to have the region around the springs declared a reservation. Not only were those efforts rebuffed in Washington, but in 1871 the federal government decided to move the Indians to an altogether different location more than fifty miles to the west, at the foot of the Tularosa Mountains. Even though this reservation proved too high and cold for comfort, and mining prospectors had begun to infiltrate the mountains, the government established the Tularosa Reservation.

In the summer of 1872, the army moved the Chihennes there, removing them from their sacred homeland. Instead of settling, however, Victorio and many members of his band hid in the recesses of the Black Range.

In July 1872 another peace emissary appeared. Brig. Gen. Oliver O. Howard met with Victorio, established a bond, and agreed that the Chihennes should return to Ojo Caliente. Executive action remained in abeyance, however, pending Howard’s effort to make peace with the powerful Chiricahua chief Cochise, who had ravaged Arizona for a decade. Howard succeeded, but in his mind, the creation of the Ojo Caliente reservation was conditioned on Cochise agreeing to move there. Cochise refused, and instead Howard established the Chiricahua Reservation for him in southeastern Arizona. Victorio believed, with good reason, that General Howard had promised that his band could immediately return to Ojo Caliente. Understandably, he felt betrayed.

The government, unable to find an acceptable alternative, at last relented and established a Chihenne reservation at Ojo Caliente in 1874. Victorio and his people rejoiced; they could now live in their sacred homeland and care for it.

But in 1877, policymakers decided to consolidate all the Apache bands at San Carlos, a hot, disease-ridden place on a parched stretch of the Gila River in Arizona. Victorio and his people were herded across the mountains to that desolate place. The men stayed only a few months before breaking away to head back toward their homes. Army patrols swarmed into the mountains of western New Mexico and edged Victorio northward until he surrendered at Fort Wingate. Not willing to care for the prisoners so close to the Navajos, who acted as scouts for the army and were enemies of the Apaches, the army moved them back to Ojo Caliente pending a decision on their future.

Still classified as prisoners of war, the Chihennes awaited the government’s decision with mounting frustration. Would they remain at Ojo Caliente, or would the army one day appear and force them to go back to San Carlos?

After two years of uncertainty and insecurity, and following yet another rumor that they were to be moved to San Carlos, Victorio had had enough. In the autumn of 1879, he declared war.

The United States had the full might of its army on its side, but several factors favored Victorio. First, of course, was Victorio himself—a splendid warrior and natural leader, who drew followers with his often-stated conviction that he would rather die than be sent back to San Carlos. Second was the physical endurance of his people, who were accustomed to traveling long distances, day and night, without rest, food, or water. Third was the tortuous nature of the country itself, the steep precipices and plunging canyons webbing the Black Range and Mogollon Mountains. The Chihennes knew every rocky height and sinuous crevice of the tangled land, and they knew how to position themselves on craggy elevations invulnerable to enemy assault and usually ideal for ambushing any pursuing force.

The Indians could also travel rapidly on fresh mounts. When their own began to break down, they simply stole remounts from the nearest ranch. (The cavalry, by contrast, had to pursue on horses that rapidly broke down in some of the most punishing mountains in the West.) Finally, the Chihennes knew well the safety offered by the international boundary: when too closely pressed, they could find refuge in Mexico.

Victorio faced a strong force, principally composed of black troopers of the 9th and 10th Cavalry, led by some of the army’s most skilled frontier fighters. The 9th garrisoned in New Mexico and the 10th in West Texas, into which Victorio’s band occasionally spilled.

Plagued in civilian life by racism and discrimination, blacks could find a better life in the military. The black regiments, therefore, boasted the highest reenlistment rates and the lowest desertion rates in the army.

Moreover, since the creation of their regiments at the close of the Civil War, they had been relegated to the harshest, most demanding sector of the Indian frontier. Their long service in the Southwest made them seasoned veterans.

So were their senior officers—all white, of course. Col. Edward Hatch commanded the 9th, Col. Benjamin H. Grierson the 10th. Both had endured their own share of discrimination. Coming out of the volunteer service in the Civil War as general officers, they attained colonelcies in the Regular Army because of distinguished wartime service. Such origins, rather than West Point and the Regulars, counted against them, as did their command of black regiments. Both passed their entire postwar careers—more than a quarter of a century—commanding these regiments.

Colonel Hatch also served as commander of the territory of New Mexico, headquartered in Santa Fe. His principal field commander was Maj. Alfred P. Morrow, a courageous, dogged field soldier who commanded all the troops in southern New Mexico, with headquarters at Fort Bayard. Once on the trail, he refused to let go.

Another advantage of this force was that the New Mexico troops borrowed Apache Indian scouts under Lts. Charles B. Gatewood and Augustus P. Blocksom from the Department of Arizona. Their skills proved indispensable in trailing the Victorio and his renegades, as well as in fighting them.

In late August 1879, before the conflict erupted, Victorio visited the Mescalero Apache agency, east of the Rio Grande in the Sierra Blanca. He recruited the aged but powerful chief Nana—his sister’s husband, who with his Chihenne band had taken refuge with the Mescaleros to escape the turmoil west of the Rio Grande—and also any Mescaleros who wished to join them. (Though geographically removed from the Chiricahuas, and from a different tribe, the Mescaleros were usually friendly and, in the Victorio War, were often allies.) Together Victorio and Nana hurried back to Ojo Caliente.

In late August 1879, before the conflict erupted, Victorio visited the Mescalero Apache agency, east of the Rio Grande in the Sierra Blanca. He recruited the aged but powerful chief Nana—his sister’s husband, who with his Chihenne band had taken refuge with the Mescaleros to escape the turmoil west of the Rio Grande—and also any Mescaleros who wished to join them. (Though geographically removed from the Chiricahuas, and from a different tribe, the Mescaleros were usually friendly and, in the Victorio War, were often allies.) Together Victorio and Nana hurried back to Ojo Caliente.

On September 4, 1879, Victorio and about forty warriors launched their war. They swept down on the horse herd of Capt. Ambrose Hooker’s Troop E, 9th Cavalry, at Ojo Caliente; killed the eight herders; and made off with all forty-six horses. They rode swiftly west into the recesses of the Black Range they knew so well.

No longer content with hiding in the Black Range, Victorio embarked on relentless war for the next two months—not solely against soldiers but also against all the white miners and ranchers who had filtered into Apache ranges. He raided and burned ranches, killed ranchers and miners, and stole horses. When pursued, he faded back into the Black Range. (Accounts of casualties vary wildly. At the end of the war, The New York Times reported four hundred deaths at Victorio’s hands; the real number is likely far smaller.)

Major Morrow managed to put troops on Victorio’s trail, buttressed by the incredible tracking skills of the army’s Apache scouts. They followed until the Indians tired of the pursuit and scattered, reuniting at a predetermined point. Sometimes Victorio’s warriors would stand and fight until forced to abandon their positions, and all their camp equipage and stock. Then they would flee in all directions. They could easily replenish both stock and provisions by raiding ranches and mining communities, taking a toll of dead defenders as they went. Panic spread throughout southwestern New Mexico, and protests and petitions bombarded President Rutherford B. Hayes, Secretary of War George Washington McCrary, and members of Congress. Territorial Governor Lew Wallace vigorously sought authority to raise a citizen militia, but failed.

During this time, numbers on both sides fluctuated. Sometimes Victorio counted one hundred or more warriors plus some women and children. (Although his own women and children remained at San Carlos, Nana and some Mescaleros had brought their families). Mescaleros came and went, swelling and diminishing his force. As Victorio sent raiding parties out of the mountains to strike ranches and mining towns, Morrow reduced his own force by dispatching troops to guard such places and pick up any possible trails.

By late October 1879, Victorio had decided to cross into Mexico to rest. He was worn out by the continued chase, which took a hard toll on the women and children, and tormented by frequent encounters with the pursuing soldiers. Much to his surprise, however, Morrow risked an international incident by sticking to Victorio’s trail even into Mexico. Since Victorio could not shake off his pursuers, he decided to attempt another ambush and destroy them. He now had about one hundred fifty warriors, probably including some from Arizona and Mexico under Juh and Geronimo. Selecting a canyon with steep, rocky slopes, he camped on the canyon floor and waited.

Unknown to Victorio, Morrow’s command had nearly destroyed itself. The merciless desert yielded almost no water, and the Apaches had drained their water tanks. Day after insufferable day, debilitating thirst plagued both men and animals. Horses and mules collapsed. Rations ran short. Morrow hoped to find water at the Corralitos River, which he judged to be only about five miles to his front, but he had no guide familiar with the country and was groping blindly for the river. The quest was interrupted on October 27, when scouts returned with word of the ambush Victorio had set up in the canyon. Morrow decided to attack.

Intending to hide his horses and attack on foot at dawn, Morrow detached half of his eighty-one cavalrymen to guard the horses and worked slowly forward with the remaining forty, along with eighteen Indian scouts under Lieutenant Gatewood. As the troopers settled in for the night, the Indian scouts crept forward to find Victorio’s camp. Warriors stationed on hills at the entrance to the canyon heard the scouts’ horses and mules braying for want of water and opened fire. His presence discovered, Morrow pushed his forty men quickly to the canyon to fight in the light of a full moon.

The troops easily routed the vedettes at the mouth of the canyon. The latter ran into the canyon to alert their tribesmen, and all scrambled up the canyon wall, where rock breastworks had been thrown up on the crest. Outnumbered more than three to one, the troopers scaled the slope, firing as they moved forward. The Indians returned fire with Winchester rifles and formed a line at the very top of the heights. The gunfire from both sides flashed vividly in the night, with increasing intensity.

Although it was aimed too high to do any damage, the Indians’ fire was so heavy that Morrow’s troops stopped the advance.

Morrow ordered Gatewood to lead the scouts in a swing to the right in an effort to flank the enemy position while his cavalrymen would simultaneously resume their assault. The scouts succeeded in getting within ten feet of the objective, but were pinned down when the Apaches rolled down big rocks from above. They fired steadily until nearly out of ammunition.

At the same time, the cavalry had almost reached the top of the canyon, but were confronted by formidable ledges of rock. Morrow’s men repeatedly tried to push through to the top. Soon they too ran low on ammunition. Recognizing the futility of further effort, at about one o’clock in the morning, Morrow pulled his command back to where the horses had been corralled. There he found them almost completely broken down. They had not had water for three days, and unless the horses were watered at once, his troops would likely be dismounted entirely.

Determined to find the Corralitos River, Morrow resolved to lead the horses there, returning to the canyon on foot at dawn to resume the battle. The river proved twelve miles distant instead of five, and he did not reach it until daylight. No less exhausted than the horses, his men dropped at once and slept. The major thought long and hard about returning to the fray. He had to acknowledge that neither his cavalry nor his scouts could probably attain the objective before expending all their ammunition. Nor were they in any condition to fight. Victorio had won.

The command turned back north and arrived at Fort Bayard on November 2. The pursuit had been long, hard, and persistent. Although he expected the Indians to return and had disposed his command at various strategic points to intercept them, Morrow consoled himself with the fact that at least he had driven Victorio out of the United States. In a tribute to the work of his men, Morrow singled out the Apache scouts from Arizona, whom he credited “entirely” with driving Victorio out of the country. Without their services, he reported, the troopers could never have followed Victorio’s trail.

Victorio moved his people east to the Candelaria Mountains, which straddled the road from Chihuahua City to El Paso. His strength grew from 60 warriors to more than 125 as Mescaleros left their reservation to join him. Early in November, Mexican citizens from Carrizal picked up the trail of one of Victorio’s raiding parties and dispatched fifteen men to follow. Victorio had laid an ambush in a pass where the road crossed the mountains: all fifteen men were killed. Alarmed by their failure to return, Carrizal dispatched a search party of thirty-five men.

They suffered the same fate.

The Carrizal Massacre led the veteran Mexican Indian fighter, Gen. Geronimo Treviño, to launch a formidable campaign to destroy Victorio. As Major Morrow had predicted, Victorio crossed back into New Mexico early in January 1880.

In an almost identical replay of his previous strategy, Victorio wove a devious course through the San Mateo Mountains, the Black Range, and the Mogollons. But he could not shake Morrow’s pursuers, who relentlessly tracked him and flushed him from strong positions, causing a few casualties and the loss of stock and camp equipment. More important, the trackers kept Victorio’s followers in a constant state of insecurity.

Once again, Morrow’s command exhausted themselves and their animals in the punishing mountains. Colonel Hatch declared California’s lava beds a lawn compared to these mountains. Morrow himself gradually broke down, physically and emotionally. On February 8, 1880, in a rare outburst of frustration, he confided to a fellow officer:

I am heartily sick of this business and am convinced that the most expeditious & least expensive way to settle the Indian troubles in this section is to employ about 150 Apache Indian scouts and turn them loose on Victorio without interference of troops except general instructions from the officer conducting the campaign. I have had eight engagements with the Victorio Indians in the mountains since their return from Mexico and in each have driven and beaten them but there is no appreciable advantage gained, they run but make a stand at another point where possibly ten men can stand off a hundred, kill a number and lose none…. I leave here tomorrow and will stick to Victorio’s trail so long as a serviceable animal or an able soldier is left but I still think that the pursuit is an unprofitable one and Indians should be employed on the principle of fighting fire with fire.

Morrow continued what he considered his hopeless campaign, both in the Black Range and, later, east of the Rio Grande. Victorio had crossed the river and taken refuge in the San Andres Mountains. They were close to the Mescalero Reservation, and he entertained hope of arranging a peace through the agent there. At the same time, though, as Mescalero warriors joined his band and left, he fended off the efforts of the agent to make contact.

Meanwhile, Hatch’s superior, Brig. Gen. John Pope, who commanded the Department of the Missouri, conceived a plan to end the war. Asking for help from the Department of Texas, he was allotted Col. Benjamin Grierson and elements of the 10th Cavalry. The first objective would be the Mescalero agency. Hatch would march from the west and Grierson from the east; they would join forces in April to disarm and dismount the Mescaleros that were on the reservation there.

Although he defended his charges, the Indian agent there had to admit that some Mescaleros had joined Victorio. In fact, Victorio relied on the Mescalero Reservation for recruiting and reprovisioning.

Strengthened by a troop of the 6th Cavalry and Lieutenant Gatewood’s Apache scouts from Arizona, Hatch had already, in late February, called together all twelve troops of the 9th Cavalry and organized them into three battalions. Morrow commanded the strongest, accompanied by Hatch. Capt. Henry Carroll led another, and Ambrose Hooker the third.

As Hatch prepared for the move late in March, he received intelligence that Victorio had been camped in the San Andres Mountains for more than a month. Before marching to rendezvous with Colonel Grierson at the agency, Hatch hoped he could converge his battalions on Hembrillo Canyon, the site of reliable springs, and destroy his enemy. If any Indians escaped to the east, Grierson, moving west from Fort Concho in central Texas, could intercept them.

Hatch almost succeeded. Ordered to approach Hembrillo Canyon from the east, Captain Carroll paused on April 7 for water at a spring that turned out to be so loaded with gypsum that it all but unfitted both men and horses. Plagued by vomiting and dysentery, his troopers could barely function. Dividing to seek pure water, they found none until Carroll himself, with two troops, discovered Hembrillo Springs—and Victorio. The Indians had fortified the springs and quickly surrounded Carroll, who, after detaching horse holders, brought only fifty sick men to the fight. Still, the unequal contest raged all night.

Carroll’s force would almost certainly have been annihilated: he himself was badly wounded, as were seven of his men, two mortally. But at daybreak, Capt. Curwen McLellan with his troop of the 6th Cavalry and Gatewood’s scouts—sent ahead by Hatch because water shortage slowed the main command—swept into the canyon from the summit of the San Andres and drove the Apaches back into the mountains.

Laboring up the mountains from the south with Morrow’s battalion, Hatch received word by courier from McLellan of the fight raging on the slopes above Hembrillo Canyon. The colonel veered at once to the west and attacked over the top of the mountains, hoping to trap the Indians between Morrow and McLellan. The move was understandable, but it was a mistake. No sooner had he changed direction than Victorio’s people flowed down the south slope of the San Andres and then continued moving away from the mountains, hiding silently as the troops marched nearby. Some turned west to cross the Rio Grande and hide in the Black Range, and the rest headed for the Mescalero Reservation.

Reporting this engagement, Hatch telegraphed a brief, confusing narrative of troop movements, but pronounced Victorio “thoroughly whipped.” General of the Army William T. Sherman directed that his congratulations be conveyed to Hatch. The victory, of course, had been Victorio’s, not Hatch’s, and Captain McLellan and his Arizona troops and scouts had conducted the only serious fighting. Even in his more detailed annual report, Hatch presented a version that is difficult to untangle.

Official reports obscured the Hembrillo Canyon action with accounts of the main purpose of the expedition—disarming and dismounting the Mescaleros. As planned, Hatch and Grierson met at the Mescalero agency on April 12: Hatch with 430 men, Grierson with 280. Combined, their force was larger than the total number of Apaches enrolled at the agency. The agent regarded most of the Mescaleros as peaceful, but had to bow to Hatch’s superior authority.

The disarming on April 16 went badly. About 320 Indians had been assembled, many of them women and children. The disarming had scarcely begun when firing broke out, and the Indians stampeded up the side of a mountain. Grierson’s cavalry charged in pursuit, bringing down several Indians with carbine fire. Between thirty and fifty escaped to join Victorio, and the rest returned quietly to their camp by evening. The soldiers recovered only a few arms, but Hatch left behind a strong guard while he turned again to chasing Victorio. Grierson returned to Texas.

After more than eight months of exhausting flight and struggle, Victorio and his people were tired. They scattered into the Black Range and the Mogollons. Victorio’s son Washington, an aggressive daredevil, pushed west with a handful of warriors to try to liberate their families at San Carlos and sign up more recruits, but troops of the 6th Cavalry turned him back decisively. Victorio himself, with the main band, endured the usual tortuous pursuit by Major Morrow and other units of Hatch’s regiment. By mid-May the troops had exhausted their mounts, which were so broken down that the soldiers had to withdraw to Ojo Caliente and resume the chase on foot.

But Victorio had grown careless. Neglecting to post his people on a defensible height, he laid out his camp in a canyon not far from Ojo Caliente. At daybreak on May 24, 1880, carbine fire ripped into his camp. Sleeping warriors scrambled to defend themselves or escape, but in every direction they ran, volleys of fire drove them back. They were surrounded. Hunkering down, they exchanged fire with their attackers all day. Victorio took a bullet in his leg, and thirty or more of his people—men, women, and children—fell dead, while many others sustained wounds. Sporadic firing continued through the next day. Late in the afternoon, the assailants withdrew, having little ammunition left and no water. The Apaches scattered back into the Black Range.

Victorio had been soundly whipped—the first decisive defeat in his long struggle. Dragging their wounded, leaving some to die, the Apaches headed in three parties for Mexico. Troops pressed from the rear until the remainder of the Indians had escaped across the border. Morrow followed one party so closely that at the border itself he had a brief skirmish in which Victorio’s son Washington was killed.

Colonel Hatch again misrepresented the success, ascribing the victory to the cavalry, with slight assistance from the scouts. In fact, not a single Regular took part in the battle. Hatch’s civilian captain of scouts, Henry K. Parker, had led some seventy Apache scouts on Victorio’s trail, discovered his camp, and during the night succeeded in posting contingents on four sides. They remained undiscovered until close enough to open the battle at dawn. Parker sent back for more ammunition, but it had not arrived by the afternoon of the second day. Almost out of ammunition and entirely out of water, he fell back to Ojo Caliente, allowing Victorio to hurry south.

His people fatigued and short of provisions, Victorio headed southeast into the forbidding Chihauhuan Desert south of West Texas. The disheartened chief did not know where to turn. Another foray into western New Mexico seemed futile. The Mescaleros with him may have tried to persuade him to dash northward to their agency and surrender, or to refit and once more take to the warpath; or he may have resolved on his own to attempt one of those two courses. In any event, late in July 1880, with 150 warriors, he forded the Rio Grande into Texas. Nana seems to have remained in Mexico, caring for the women and children.

After leaving the Rio Grande, their survival as they crossed West Texas depended on having enough water for the horses and men.

Few reliable sources existed. One, called Tinaja de las Palmas, lay in Quitman Canyon. On the morning of July 30, Victorio approached the spring from the south but discovered that a handful of the 10th Cavalry commanded by Colonel Grierson held a commanding height.

Following the fiasco at the Mescalero agency in May 1880, Grierson had returned to Texas, deciding to remain there and make certain that Victorio did not try to cross West Texas to return to New Mexico. Concentrating eight troops of the 10th Cavalry and four companies of the 24th Infantry at Fort Davis, he had strung his units along the Rio Grande at every water hole and other strategic position.

At Tinaja de las Palmas on July 30, Grierson held the height above the spring with only himself, his young son Robert, and twenty-three troopers. Yet he knew that if he could hold Victorio there, other units could be summoned to the battle.

As Victorio turned to bypass the spring on the east, ten soldiers rushed out to confront him. Both sides formed skirmish lines and exchanged fire for about an hour. Suddenly Victorio spotted a large body of cavalry charging toward the battleground from the east. First on the scene were two troops of cavalry, under Capt. Charles D. Viele, that had been posted at Eagle Springs. The skirmish lines dissolved as the ten soldiers withdrew to their defenses and the reinforcements fought their way through to join the beleaguered few. Desperate fighting continued for another hour, when still another force of horsemen charged into the fray: Capt. Nicholas Nolan’s troop, which had been camped farther west in Quitman Canyon. Outnumbered and outfought, Victorio turned back to Mexico.

Undeterred, he tried again a few days later. After a brief skirmish with soldiers on August 4, he slipped through the screen and raced north on the west side of the forbidding Sierra Diablo Range. He knew that in a canyon draining the east side of the mountains lay vital water, Rattlesnake Springs. Descending the canyon on August 6, he discovered soldiers posted to command the springs.

Grierson, anticipating Victorio’s return and tipped off to his location, had led two troops of cavalry in a punishing dash up the east side of the range, marching sixty-five miles in twenty-one hours to reach Rattlesnake Springs before Victorio. Two more troops under Capt. Louis H. Carpenter joined him there.

Victorio attacked, but heavy fire drove his men back into the mountains. Late in the afternoon they sighted a wagon train approaching from the southeast and galloped out of the mountains to attack it. A formidable force of black foot soldiers with long rifles surrounded the wagons and stopped the attack. At that moment, horsemen charging from Rattlesnake Springs hit the Apaches in the rear, and they fled to the southwest, into a mountain range. Water, held by hard-fighting soldiers, had again confounded Victorio’s drive toward the Mescalero agency. He returned to Mexico.

Grierson would play no further part in the conflict, contenting himself with sealing off the Rio Grande to prevent another attempted crossing. That achievement, however, is a tribute to his leadership and the fortitude and courage of his black troopers.

Victorio and his people neared the limits of their endurance—limits Apaches rarely reached. Exhausted, hungry, thirsty, almost out of ammunition, and abandoned by many of the Mescaleros, they thought they had run out of options. Victorio knew one remained, but hesitated for days. At last he decided to strike directly west and join Juh in the Sierra Madre.

Victorio soon discovered, however, that even the Chihuahuan Desert afforded no safety. In September 1880, Mexican Col. Joaquín Terrazas scoured the country with a force that grew from two hundred to more than three hundred as volunteers enlarged his command. Believing himself distant from his foes, Victorio slowed and instructed scattered groups to unite at a lake near three low, rocky peaks called Tres Castillos. On the afternoon of October 13, 1880, the bedraggled band spread over a grassy plain bordering the lake. It was an ideal place to rest, feed and water their horses, and feast on recently killed cattle.

With a large fire blazing to cook the meat, the Indians relaxed as night began to descend. Suddenly rifle fire erupted from all directions, the flashes reflecting on the surface of the lake. Seeing the fire came from all sides, Victorio ordered his people to scale the rocky heights of the nearest of the three low mountains. Quickly they worked themselves up among the boulders and crevices and hid themselves to wait out the long night.

At daybreak Mexican soldiers swarmed up the slopes, seeking out Indians in their hiding places and killing them. For two hours the warriors fought back, until they had exhausted their ammunition. Stories abound of how the chieftain died: the most reliable, told by the Apache who found his body, is that he fatally stabbed himself with his knife. Only a few escaped who had been with him. Some sixty-eight women and children were taken into captivity and—perhaps tragically, considering the background of many of the black troopers who had hounded Victorio’s band into the hands of Terrazas—sold into slavery in Mexico.

Colonel Terrazas lost three men killed. He went home to Chihuahua City in triumph, an even greater hero for having achieved glory without any help from American soldiers.

Not all of Victorio’s followers had been present at Tres Castillos. Most important, old Nana had been absent with some of his people. He inherited the mantle of Victorio and headed west for the Sierra Madre, where Juh welcomed him. Despite his age and his physical infirmities, Nana remained a powerful leader.

He took revenge. “Nana’s Raid” ravaged southwestern New Mexico for a month in the summer of 1881, killing between thirty and fifty whites and capturing herd after herd of horses, all while reenacting Victorio’s success in eluding pursuing troops. It was a fitting tribute to the extraordinary leadership of the brilliant but tragic leader of the Victorio War of 1879–80.

Nana then allied himself with Geronimo and surrendered with him in 1886. He died ten years later, surely well beyond eighty years old. Today neither Victorio nor Nana is remembered as well as the less-talented Geronimo, a tribute to the power of a media and popular culture that have turned that chief’s name into a war cry for the ages. MHQ