In 1966, the country with the most heavily defended air space was not the United States, the Soviet Union or China. It was North Vietnam. A well-developed triad of anti-aircraft guns, surface-to-air missiles and MiG fighter planes made it the most dangerous place in the world for American pilots. Yet week after week U.S. aviators were sent into the firestorm to hit North Vietnamese targets, and many didn’t come out. One of those who went down was U.S. Air Force Capt. Victor Vizcarra, a F-105D Thunderchief fighter-bomber pilot—and his plane wasn’t even touched by a North Vietnamese weapon.

Recommended for you

Vizcarra’s journey to Vietnam began with admiration for his brother Gilbert, 15 years his senior, who enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1942 and became a fighter pilot in World War II. Victor, born Oct. 13, 1936, in Los Angeles, learned of his brother’s heroics through talks with their father.

“My dad would tell me stories about what Gil was doing in the war so I wouldn’t forget him,” Vizcarra recalled in an extensive interview for this article. “I was in awe of him and wanted to be just like him. He finished his combat tour with 153 combat missions. He was the greatest influence in my life.”

pilot in training

In January 1960 Vizcarra joined the Air Force through the ROTC program at Loyola University in Los Angeles. He was called to active duty in March 1960 and went to Spence Air Base in Moultrie, Georgia, for primary flight training. Then it was on to Reese Air Force Base in Lubbock, Texas, for basic flight training and his pilot’s wings. In November 1961, Vizcarra graduated from a six-month program at Luke Air Force Base in Glendale, Arizona, to train him for the F-100 Super Sabre fighter-bomber.

After advanced training he was assigned in April 1962 to the 309th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 31st Tactical Fighter Wing, at Homestead Air Force Base in Florida. In 1963, Vizcarra received orders for an F-105 assignment and reported to Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada that August. His next stop was Itazuke Air Base in Japan on Dec. 31 with the 80th Tactical Fighter Squadron, part of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing.

On Aug. 2, 1964, three North Vietnamese vessels attacked a U.S. destroyer in the Gulf of Tonkin. In response, President Lyndon B. Johnson on Aug. 5 ordered airstrikes against North Vietnam. The 80th TFS deployed to Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base on Oct. 30, 1964, and remained there through December.

“Our combat missions were very limited during this deployment,” Vizcarra said. The squadron mainly provided air cover for search and rescue efforts to save downed aircrews. Vizcarra was credited with eight combat missions on that deployment.

The air war heated up on March 2, 1965, with the beginning of Operation Rolling Thunder, a campaign of continuous bombing that U.S. officials hoped would force North Vietnam to abandon its efforts to overthrow South Vietnam. “The planners at the Department of Defense estimated the campaign would last six to eight weeks,” Vizcarra noted. “It lasted 44 months and never achieved its goal.”

The 80th TFS was stationed at Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base from mid-July through the latter part of August 1965. During this time, Vizcarra flew 29 Rolling Thunder missions in F-105 Thunderchiefs, “Thuds,” including “the first strike against a surface-to-air missile site in the history of aerial warfare,” he said. The Air Force lost six of the 46 Thuds involved in the attack on those SAMs, Vizcarra added.

In September 1966, Vizcarra and two other pilots from the 80th TFS deployed to the 354th TFS at the Takhli air base. The move sent him on more SAM suppression missions.

eject! Eject!

The mission on Nov. 6, 1966 would be the one Vizcarra could never forget. Capt. Glen Davis, in an F-105 designated Clipper Lead, and Vizcarra, Clipper 2, were looking for three suspected SAM sites just above the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Vietnam.

Suddenly Vizcarra’s aircraft suffered a “hellacious” engine compressor stall.

“I initially believed I could nurse the plane back to Takhli,” Vizcarra said. He jettisoned six M117 750-pound bombs to lighten the plane. “But that didn’t help, and I couldn’t maintain my altitude. It soon became obvious I was going to have to eject.”

After informing Clipper Lead, he pulled up the seat armrest ejection handles and waited for the canopy over the cockpit to jettison. “But nothing happened,” Vizcarra added. “I thought that the system had failed and that I was going to have to blow myself through the canopy!”

He squeezed the ejection trigger in each armrest. The canopy jettisoned and the seat followed.

Vizcarra took a last look at the cockpit instruments: airspeed 172 knots (about 200 mph) and altimeter 3,700 feet. At that altitude, he was just 1,700 feet above the terrain—300 feet below recommended minimum ejection altitude.

“The seat ballistics took me in a large backward somersault where I was inverted at the peak of the arc,” Vizcarra said. “At about the peak of the somersault, my seat belt and harness opened automatically, and the butt snapper forced me out of the seat.” The butt snapper is webbing that conforms to the shape of the seat but is stretched taut during the ejection process, bouncing the crew member out of the seat. Without it, Vizcarra explained, “too many individuals would tense up and never let go and ride the seat all the way to their deaths.”

eerie landing

The shock from the opening of his parachute was “very mild” because of the extremely low airspeed at ejection, Vizcarra said. “Even though I had never bailed out before, prior training automatically started me going through procedures of checking my chute for any torn panels or twisted lines, and I found everything in perfect shape.”

The ejected pilot saw an F-105 flying below and close to him. “At first I was ready to cuss out my lead for flying so close to me, but then realized it was my plane,” Vizcarra said. “I watched it as it proceeded in a gradual descent and then slowly turned left and crashed into a mountainside with a resounding explosion.” It’s an image that still haunts him.

Vizcarra had ejected east of the North Vietnamese/Laotian border and just south of Mu Gia Pass, used by North Vietnamese supply trucks to reach the Ho Chi Minh Trail. It was about 3:30 p.m.

“I was surprised how quiet it was with only the sound of wind rushing through my helmet as I floated down towards the thick jungle below me,” Vizcarra remembered. “I pulled the release handle on my survival kit attached to my butt, which, when released, would hang below you by an almost 20-feet lanyard. I prepared for a landing in the trees. I put my feet close together and one arm on the parachute risers behind my head and the other arm on the front risers, making myself as streamlined as possible.”

Actually, “a landing in the trees” isn’t precisely what happened. “It was more like an uncontrolled crash!” Vizcarra said. “It was a very sudden stop. In addition to ending up tangled upside down in the tree, it also knocked the wind out of me. Hanging upside down from my right ankle wedged in a fork of a branch, it was nearly impossible to determine my height from the ground.”

After several strenuous attempts to bend upward, grab the branch holding the wedged ankle and pull himself up, Vizcarra finally succeeded. But he still didn’t know how far he was from the ground. Jungle trees in Southeast Asia can grow as high as 200 feet. To gauge the distance, Vizcarra dropped his helmet. He saw it vanish into the jungle undergrowth. He still had no idea of where the ground was.

“In desperation, I foolishly chanced it and released myself from my chute hoping I was not too high up,” Vizcarra said. “To my surprise, I dropped about 6 feet, which meant when I was hanging upside down, my head was only about 3 feet from the ground!” He had narrowly missed crashing headfirst to his death.

On the ground, Vizcarra put into practice what he learned during Survival Training School at Stead Air Force Base in Reno, Nevada. First, he turned off the beeper beacon that would identify his location to rescue crews because it might interfere with his emergency survival radio.

hopes of rescue

Vizcarra made contact with Clipper Lead pilot Davis, who instructed him to conserve radio power by turning the device off for 15 minutes until search-and-rescue forces arrived. Vizcarra sat on the jungle floor to wait.

“I quickly realized that although I was in thick jungle undergrowth, it wasn’t thick enough to conceal me,” Vizcarra said. He moved northward toward karst mountains—limestone rock weathered into cliffs, sinkholes and, most important to Vizcarra, caves. He had noticed the outcrops as he parachuted into the jungle.

“I reached the base of the karst after traveling around 200 yards up an incline,” he said. “Several cave entrances came into view, providing excellent concealment opportunities.”

Vizcarra soon found a good hiding place. “I entered the nearest cave directly in front of me and was surprised by how dark it was after only taking a few steps into the cave,” he said. “I had to stop and let my eyes get accustomed to the darkness. I was amazed. The cave was like a labyrinth with various corridors.”

He picked a corridor to his left and followed it about 10 feet, then turned right into another corridor. Going an additional 10 feet, he saw an indentation in the passageway. Vizcarra decided that he could conceal himself in there. By leaning forward and looking back toward the spot where he entered, he would be able to see intruders silhouetted against the backlight of the main entrance. He was now able to rest.

“I finally had time to reflect on what had happened,” Vizcarra said. “I thought of my family for the first time, wondering how my wife would react when they informed her I was down. I thought of my two sons. They were 5 and 6—old enough to remember me if I didn’t get rescued. I thought of my daughter. She was three weeks short of being a year old—too young to remember me if I didn’t get rescued. For the first time, I felt pangs of despair. I turned to my faith and said a little prayer asking God to help me get out of this place!”

Almost immediately, he heard the sound of jets flying overhead. They were F-105 Thunderchiefs, although Vizcarra didn’t know it at the time. “I rushed out of the cave and heard Clipper Lead calling me as I turned on my survival radio,” he said.

Davis told Vizcarra that search-and-rescue aircraft were on-site. The rescue helicopter, not identified to Vizcarra, was a UH-2A Seasprite, dubbed the “Grey Ghost” by its crew, members of the Navy’s Helicopter Combat Support Squadron 1 stationed on the destroyer USS Halsey in the South China Sea. The helicopter was accompanied by Air Force A-1 Skyraider single-seat, propeller planes that were designed as fighter-bombers but also served as escorts on rescue operations. While on rescue duty, Skyraiders used the call sign Sandy.

Davis radioed that Sandy 7 would be in charge. Sandy 7 immediately told Vizcarra to press and hold down his radio button for a “long count” to give Sandy’s ADF (automatic direction finder) time to get a fix on Vizcarra’s radio signal.

Vizcarra replied with his count: “Clipper 2, five, four, three, two, one, and repeated the count back up to five.” Sandy 7 determined Vizcarra’s location and flew directly over him. Vizcarra radioed, “Sandy 7, you just flew over me!” Sandy 7 didn’t acknowledge, and Vizcarra thought the pilot might not have heard him. (After he got back to Japan and was reviewing the transcripts of radio transmissions, Vizcarra learned that Sandy 7 didn’t respond because he was concerned that the enemy might be monitoring the American radios and would be able to pinpoint Vizcarra’s location.)

At the time of the planned rescue, the sky was “almost a total overcast,” Vizcarra recalled, “with only one nearby sucker hole [a clearing in the clouds]. I heard Sandy 7 radio his wingman that he thought he could spiral down through the sucker hole and get below the clouds. All I could see were the tops of the karst disappearing into the low overcast with very little room for staying in visual conditions.”

The clock added to the pressure. Only 30 minutes of daylight were left.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

royal lancer

The rescue helicopter, call sign “Royal Lancer,” was cleared to conduct the operation. “I picked up the distant sound of a helicopter one valley over,” Vizcarra said. “I told him I was northwest of his location and to come over one valley. He acknowledged. My excitement increased as the sound of the chopper increased as he approached my position. I finally got a partial glimpse of him through the top of the thick foliage as he traversed from left to right over my parachute hung up on the tree.”

Vizcarra radioed, “You just flew over my chute! Do you have it in sight?” The chopper pilot acknowledged in the affirmative. Vizcarra excitedly responded, “OK, I’m only 200 miles north of my chute!” He then heard an inquisitive voice: “You’re where?” Vizcarra corrected himself: “Negative, negative. I mean I’m 200 yards north of the chute.” The rescue copter moved sideways toward Vizcarra, who popped a smoke flare to mark his location.

As the chopper neared, its downwash kicked up debris from the jungle floor and broke branches off trees. One hit Vizcarra on the head, but it was small and didn’t cause much of an injury, he said. The noise of breaking branches increased as the chopper stopped, hovered over him and lowered into the trees a rescue hoist called a “jungle penetrator.” Vizcarra only had to take one step to reach the penetrator. He thought to himself, “These guys are good!”

Vizcarra unzipped the hoist’s canvas cover and pulled down three petal-shaped pieces of metal that folded out to an anchor-like seat. He positioned himself over the petals, sitting on one and straddling a leg over each of the other two. The next step was to secure the safety lanyard around himself and snap the clasp in place on the hoist, but Vizcarra—trying to do all of that with one hand while holding his radio in the other—was having a difficult time opening the clasp.

“The spring in the clasp was either bent or rusty, but I couldn’t open it all the way with my thumb,” he said. “Every time I tried to hook the security line up, the clasp would bounce off because of it not being fully open.”

running out of time

As Vizcarra struggled, someone with a megaphone in the helicopter called for him to hurry up. The helicopter was running low on fuel. After the third call from the helicopter, Vizcarra gave up on his attempt to secure the lanyard and was going to radio “OK, I’m ready,” but he got out only “OK” before he was jerked up suddenly.

“I lost hold of my radio as I reached for the cable with both hands,” he said. “The ascent was relatively quick while I held on to the cable for dear life, unsecured.”

It was a jarring experience. “I don’t like heights unless I’m in an airplane, so I closed my eyes while they pulled me up,” he said. But he opened them upon hearing a “squeaking noise” above him that was increasing in loudness. The sound was the hoist cable rubbing against a tree branch. The hovering helicopter had drifted from its initial position, which meant the cable was no longer hanging straight down.

“My rise to freedom stopped as my shoulder reached the branch,” Vizcarra lamented. “My rescuers had to stop and lower me a few feet and try using my shoulder several times as a battering ram to break through the branch!”

Once free of that barrier, Vizcarra continued his ascent. Eventually, he cleared the trees.

The chopper tilted nose down and started to speed away. “I finally felt someone grab the collar of my flight suit at the nape of my neck and pull me into the chopper,” Vizcarra said. He checked his watch and figured that in about 40 minutes the helicopter would be touching down at Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Air Force Base, where a U.S. Air Force helicopter rescue squadron was based. From ejection to rescue, Vizcarra had been on the ground for about two hours.

After a little while, Vizcarra was handed a life preserver, “which I thought was strange,” he said, “All of this just to cross the Mekong River?” He was unaware that he had been hoisted into a Navy helicopter.

Later a crewman “opened the chopper door and started dumping out anything that wasn’t tied down, the machine gun, ammo cans, etc.,” he recalled. “I wondered what the heck was going on when all of sudden I remembered their pleas for me to hurry up because of being low on fuel. I wondered how close these guys had cut it.”

Close to the 40 minutes he had estimated for the flight to Nakhon Phanom, Vizcarra felt the chopper start to decelerate, begin a descent and land. “When I jumped out of the chopper, instead of being on terra firma as I expected, I was shocked when I got hit in the face by the spray of salt water and a bunch of flashing light bulbs.”

go navy

To his great surprise, Vizcarra was on a Navy ship. “All this time I had been thinking I had been saved by the Air Force,” he said.

Vizcarra learned that this was the helicopter squadron’s last duty day on the Halsey. “I was their eighth rescue that cycle and their first land rescue,” he said. “It was an emotional rescue for the unit. They were still reeling over their most recent attempted land rescue, which had been unsuccessful. The unsuccessful experience propelled the unit to go to extremes in my rescue, staying on station way below ‘Bingo Fuel,’ the amount of fuel needed to get back home.”

The squadron’s noncommissioned officer in charge, Petty Officer 1st Class Curtis Venable, stationed on the Halsey’s bridge, had recognized during the rescue that the helicopter’s fuel situation was critical. He recommended that Capt. Julien J. LeBourgeois, the Halsey’s commander, turn the ship around and race toward the returning helicopter at maximum speed, 34 knots (39 mph). When the chopper landed on the ship, it had just two minutes of fuel left.

By the time Vizcarra arrived at the Halsey, it was night, and from inside the helicopter he couldn’t see where the chopper landed.

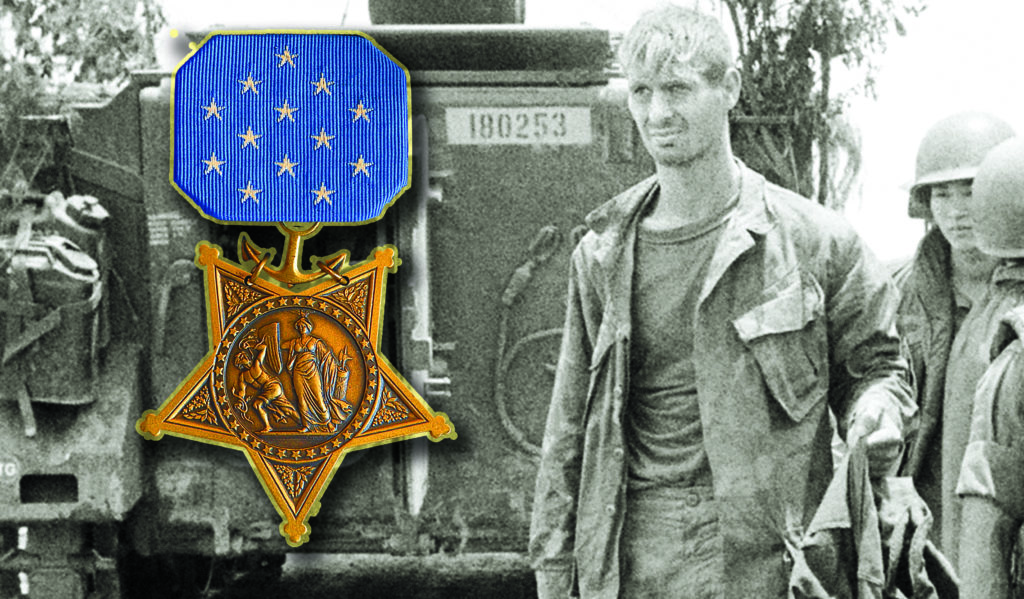

As he departed the Seasprite and discovered he was on a ship’s landing deck, a look of bewildered astonishment appeared on the Air Force captain’s face—a moment captured in a Navy photographer’s picture. Next to Vizcarra in the photo is Navy Airman Recruit P.J. Meier. The UH-2A’s crew included pilot Lt. Robert Cooper, co-pilot Lt. j.g. William Ruhe Jr. and Airman Recruit Robert J. Wall.

The photo, which became one of the war’s iconic images, was the subject of a humorous caption contest among the ship’s crew. The winner: “A ship? I thought I was being rescued!”

Vizcarra returned to Vietnam in 1970 as an F-100D Super Sabre pilot assigned to the 35th Tactical Fighter Wing, 352nd Tactical Fighter Squadron, at Phan Rang, South Vietnam. He retired from the Air Force as a colonel in 1984 after 24 years of service and just short of 3,600 flight hours—2,694 of which were in four different military jets. V