The term “war hero” is unlikely to conjure an image of a soft-spoken, devoutly religious conscientious objector whose childhood ambition was to become a doctor or missionary. But Army Pfc. Desmond Doss, a Seventh-day Adventist who didn’t smoke, drink, curse, eat meat or carry a weapon, displayed unimaginable heroism over a three-week period in 1945 on Okinawa, during the bloodiest battle of the Pacific. Exposing himself for many hours to heavy enemy fire, the young medic from Lynchburg, Va., saved dozens of his fellow infantrymen, earning him the Medal of Honor. Doss was the first conscientious objector to earn the U.S. military’s highest award.

Doss grew up in a working-class family during the Depression. After one year of high school, the 18-year-old went to work as a carpenter at a defense housing project in Newport News, then moved over to the Newport News Shipyard as a ship joiner, where he could have sat out the war doing vital defense work. “My boss offered me a deferment,” Doss said in 2001, “but I felt like it was an honor to serve God and country according to the dictates of my conscience.”

So the young man joined the Army on April 1, 1942, although his faith forbade him to bear arms. Since he wouldn’t carry a weapon, the Army assigned Doss as a medic to the 307th Infantry Regiment of the 77th Infantry Division. “I specifically requested medical duty,” Doss said, “because I felt that while I could not kill, I could help save human life.”

During training and stateside assignments, Doss faced continual harassment over his religious beliefs. He was mocked at prayer and ridiculed for refusing to carry a weapon. The harassment ended abruptly when the 77th, the Empire State Division, got into the war in July 1944. From the start Doss displayed courage under fire, first during the liberation of Guam, and then at the battles on Leyte. But it was his actions during the fighting on Okinawa that earned Doss the nation’s highest military honor and the nickname “Wonder Man of Okinawa.”

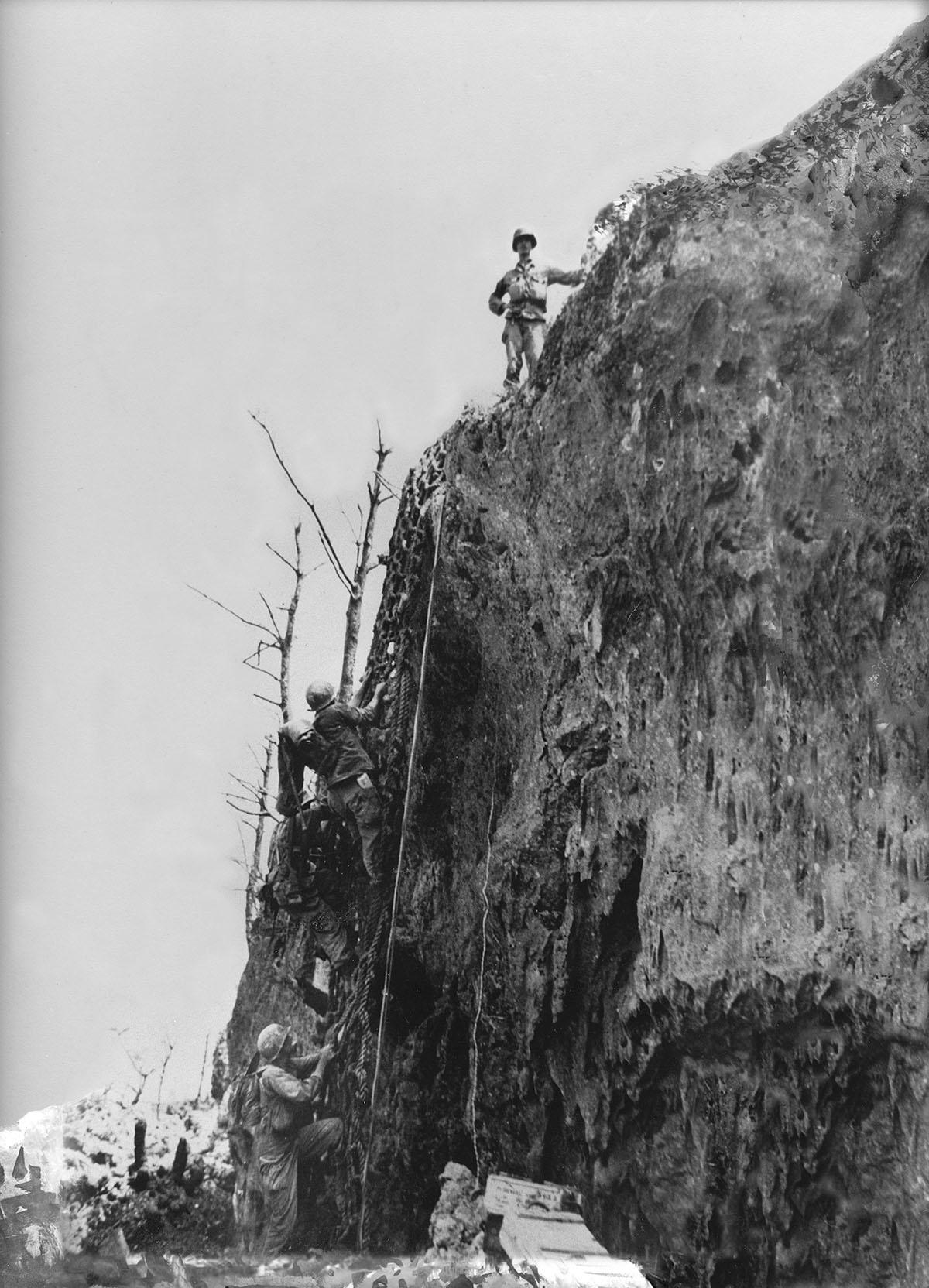

The 77th Infantry arrived on Okinawa on April 28 and immediately jumped in against the dug-in Japanese. From April 29 to May 21, Doss was in the thick of battle, tending the wounded. That first day he was credited with rescuing some 75 men pinned down by artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire atop a 350-foot escarpment known as Hacksaw Ridge. “Pfc. Doss refused to seek cover and remained in the fire-swept area with the many stricken, carrying them one by one to the edge of the escarpment and lowering them on a rope-supported litter down the face of the cliff to friendly hands,” reads his official Medal of Honor citation. His commanding officer, Doss said, “said later they wanted to credit me with 100 lives [saved], but I said 50, and they finally settled for 75.”

Doss wasn’t finished. On May 2, facing heavy machine-gun fire, he ventured out 200 yards in front of American lines to drag a GI to safety. On May 4, he made separate trips under fire to treat and save four wounded men within 25 feet of a heavily defended Japanese cave. On May 5, Doss carried a wounded officer 100 yards to safety despite enemy shelling and small-arms fire.

On May 21, during a night attack, while tending to wounded GIs, Doss was hit in both legs by grenade shrapnel. Rather than draw other medics away, he dressed his own wounds. Five hours later, while finally being carried from the battlefield on a stretcher, Doss got off and directed other medics to help a more seriously wounded soldier, only to be struck in the arm by enemy fire. Using a broken rifle stock as a makeshift splint, he crawled some 300 yards to an aid station.

On Oct. 12, 1945, President Harry Truman awarded Doss and 14 other men the Medal of Honor at a ceremony on the White House lawn. “I’m proud of you,” Doss recalled Truman saying. “You really deserve this. I consider this a greater honor than being president.”

After the war, Doss spent some six years in military and Veterans Administration hospitals and spoke about becoming a florist. But he was never again physically able to work a full-time job. Instead, he accepted public speaking engagements and assisted with Seventh-day Adventist scouting programs. The self-described “conscientious cooperator” died of a respiratory ailment at age 87 on March 23, 2006.

Originally published in the October 2008 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.