Most of the topography that figured in Civil War campaigns is remembered as a military landmark simply because opposing armies collided there. The Miller Cornfield at Antietam and the Rose Wheatfield at Gettysburg were no different from thousands of other mid-19th-century cornfields and wheatfields in America. Kennesaw Mountain and Missionary Ridge were indistinguishable folds in vast mountain ranges. Antietam Creek and the Rappahannock River were just two of the many waterways that drain the continent. The fortunes of war made them legends in military history.

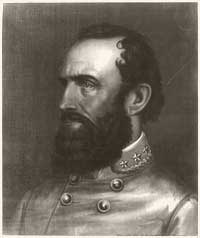

There were, however, a handful of man-made topographical features that actually affected the conflict’s course and its outcome. Some were massive civil engineering projects that gained prominence because they facilitated marches and maneuvers or affected the fighting. A great example is “the abandoned grade of the Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad,” generally referred to as the “unfinished railroad,” which arcs and dips across the northern perimeter of the Manassas battleground in Virginia. In August 1862, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson settled his soldiers behind the abandoned railroad grading and awaited developments. The developments, which came in short order, turned out to be the Second Battle of Manassas.

Unfinished railroads figured in at least four major eastern Civil War battles: Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Wilderness and Second Manassas. Only at Second Manassas, however, did an uncompleted railroad bed actually define the battlefield—in the sense that a battle was fought there largely because of the abandoned railroad grade.

On a hot Thursday, August 28, 1862, Jackson’s Left Wing of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was resting several hundred yards north of the Virginia crossroads hamlet of Groveton. From its position, it looked down at the Warrenton Turnpike. The men crowded together under the shade of the trees that afternoon. Some, including Jackson himself, were napping in fence corners.

They were posted behind the abandoned grade of the Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad. Work on the line had ceased nearly four years earlier, and it was slowly becoming overgrown. Weeds, cedars, grass and brush were beginning to obscure the straight-engineered lines. Farm fences encroached on the right of way, some even running along the railroad bed itself. But the excavations and embankments of the unfinished railroad were still largely intact—and for a commander in search of an advantageous position, these were distinctive and very welcome. It would be almost two years before tactics included the formal use of dug trenches and prepared positions. In the meantime, fortuitous “found” fortifications such as this were ideal for Jackson’s purposes.

The worn-out Rebels had just been through several arduous days. They had marched some 60 miles in 72 hours, bewildering, eluding and outflanking the Union Army of Virginia, under the command of General John Pope. The night before, these Confederates had captured Manassas Junction, Pope’s base of supplies and a massive Union depot. After eating all they could consume and packing up all they could carry, the Rebels set fire to tons of stores, ammunition and railroad rolling stock, then disappeared into the shadows.

The next day Jackson’s men rested near the unfinished railroad line, their encampment humming like “a beehive on a warm summer day,” in the words of staff officer W.W. Blackford. Though there was some effort at concealment, they were waiting to be found. And General Pope was working hard to find them.

Stonewall had chosen his ground well. A year earlier, Union infantry had noted the potential military value of the unfinished railroad when they marched along and then across it, en route to Sudley Ford and First Manassas. Now Jackson had placed his corps, protected and out of sight, behind the railroad embankment. They were positioned to intercept and attack any unsuspecting Union troops marching east along the Warrenton Turnpike, several hundred yards to the south. Jackson’s troops were also in a position to link up with the rest of the Confederate army that was scheduled to turn east and pass through Thoroughfare Gap in the Bull Run Mountains, maneuvering in such a way as to threaten Washington. And if anything went awry, Jackson could retreat northwest, toward Aldie, and escape any combination of forces that General Pope could throw together to try and stop him.

Stonewall had chosen his ground well. A year earlier, Union infantry had noted the potential military value of the unfinished railroad when they marched along and then across it, en route to Sudley Ford and First Manassas. Now Jackson had placed his corps, protected and out of sight, behind the railroad embankment. They were positioned to intercept and attack any unsuspecting Union troops marching east along the Warrenton Turnpike, several hundred yards to the south. Jackson’s troops were also in a position to link up with the rest of the Confederate army that was scheduled to turn east and pass through Thoroughfare Gap in the Bull Run Mountains, maneuvering in such a way as to threaten Washington. And if anything went awry, Jackson could retreat northwest, toward Aldie, and escape any combination of forces that General Pope could throw together to try and stop him.

Over the next fateful days, Stonewall and his corps made good use of their position. As it turned out, they would desperately need every single advantage that the cuts, fills, culverts and dumps of the abandoned grade afforded them. General Robert E. Lee’s tactic at Second Manassas was to let Jackson’s men hold the attention of the Union forces and bear the brunt of the fighting. Lee meanwhile pulled the rest of his army together on the Union left and unleashed a devastating flank attack that effectively swept Union forces off the field. Without the sturdy fortifications afforded by the unfinished railroad grade, Jackson would never have been able to withstand repeated Union assaults and hold on long enough for Lee’s plans to mature and succeed.

The unfinished line’s history actually dates back to 1850. In March of that year, the Virginia legislature passed an act allowing for the incorporation of the Manassas Gap Railroad. Alexandria, Va., was to have railroad service via the soon-to-open Orange & Alexandria Line, but the town’s markets also desired rail line access to the rich agricultural resources of the Shenandoah Valley. That ambition was reciprocated by the farmers of the Valley, who had long been isolated from Eastern markets by the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Once it was determined that the Manassas Gap in the Blue Ridge could be engineered to a grade suitable for railroad traffic, the principal roadblock to financing the project was removed. A group of investors decided to undertake building a rail line from Harrisonburg north to Strasburg in the Valley, then east through the Blue Ridge to the tiny hamlet of Tudor Hall. At that point the projected railroad would connect with the newly laid tracks of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, effectively establishing a route for the products of the Shenandoah Valley to reach Alexandria’s bustling markets. The new line was named the Manassas Gap Railroad, after the most prominent geographic feature on the chosen route.

The investors elected Edward Carrington Marshall president of the new venture. Marshall was the son of John Marshall, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and America’s most famous jurist. Previously disabled by a fall, Edward Marshall still managed to get around with the aid of a crutch and a cane. What he lacked in mobility he seemed to make up for in enthusiasm and determination. Unfortunately, he suffered from another handicap, an inability to draft realistic and achievable long-term plans, that would affect the new rail line.

Surveying of the new line was soon underway. By September 1851, the railroad was graded, ties were being placed and a section of the line was ready to be laid with “T” pattern rails made of expensive, heavy-grade English iron. Within another year, Marshall relayed cheering news to his fellow investors: Rails were laid, engines had been bought and rolling stock had been purchased. Trains were already running on a 29-mile stretch of track between Rectortown and Manassas Junction, as Tudor Hall had now been renamed. Within another two years, the rails were open to Strasburg. The Shenandoah Valley, with its rich agricultural bounty, was now officially open for business.

Only then was a decisive, possibly fatal, flaw in the Manassas Gap Railroad business model uncovered. Between Manassas Junction and Alexandria, the new railroad shared the existing track of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. It was discovered that the fees paid for this privilege made the profitability of the new line problematic. The scale of charges that had been agreed upon gave the Orange & Alexandria Railroad

15 cents for moving a barrel of Valley flour the 30 miles from Manassas Junction to Alexandria. But the Manassas Gap Railroad was charging only 15 cents to move that same barrel of flour the 60 miles from Strasburg to Manassas Junction. This put the line into an untenable financial situation.

Marshall decided that the solution was the establishment of a new “Independent Line” of the Manassas Gap Railroad, intended to bypass the Orange & Alexandria tracks and bring the Manassas Gap Railroad by an uninterrupted route to Alexandria—and profitability. By 1854, the company had begun construction of the bypass. It was to run from Alexandria northwest up the valley of Indian Run, through Fairfax Court House, across the Little River Turnpike and on toward Chantilly Post Office. At this point it would turn slightly south and make its way into what turned out to be military history. It would cross Cub Run and then Bull Run near Sudley Church, running close behind a small farm operated by a tenant named Brawner. It would then link up with the existing Manassas Gap Railroad’s main line at Gainesville.

The fledgling railroad soon found itself overextended. Officials had set about grading the entire length of the newly surveyed line, so that all the rail beds could be completed at the same time. Marshall then launched another ambitious project simultaneously—a further extension of the railroad to be called the Loudoun Branch, which was to serve the extensive coal fields of Hampshire County in western Virginia.

By 1858, a great deal of work had been carried out on the Independent Line. Most of the grading was done, and masonry was in place for some of the proposed bridges, including massive, fitted stone abutments at Bull Run and at Cub Run. But it was estimated that an additional $900,000 would be required before the line was operable. That represented a lot of barrels of 15-cent flour—far too many. It was a sum that exceeded the company’s means.

A failed wheat crop contributed to hard times in the Shenandoah Valley in 1857 and 1858, adding to the difficulties of the struggling railroad. By the end of 1858, work on the Independent Line had been suspended. In his report to stockholders in 1859, Marshall informed his investors that work would be renewed with the “utmost vigor” when a “better day dawns….”

Though no one suspected it at the time, the practical history of the Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad was already over. No further work would ever be done on the grading or masonry, no ties would ever be set, no rails would ever be laid, no locomotive or rolling stock would ever be carried over Cub Run or Bull Run. Marshall looked forward to better days, but the days just ahead would prove unimaginably bad.

.jpg) In 1861 the railroad’s investors learned that the harsh environment of war was far worse for business than the routine exigencies of tight money, business downturns and crop failures. One of the first blows to the line came when Union forces crossed the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., and occupied Alexandria. Among the prizes of war seized by Federal forces were 1,100 tons of “T” pattern rails made of heavy-grade English iron earmarked for the Independent Line.

In 1861 the railroad’s investors learned that the harsh environment of war was far worse for business than the routine exigencies of tight money, business downturns and crop failures. One of the first blows to the line came when Union forces crossed the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., and occupied Alexandria. Among the prizes of war seized by Federal forces were 1,100 tons of “T” pattern rails made of heavy-grade English iron earmarked for the Independent Line.

The main line of the Manassas Gap Railroad also made an indelible mark on military history in the war’s first major campaign. The Confederate government decided to defend the entire Confederacy at its borders. Given that decision, control of the Manassas Gap and Orange & Alexandria railroads was a necessity. That meant, among other things, defending Manassas Junction. For the first time in history, railroads would be a vital component in a military equation. The validity of this tactic was borne out at First Manassas in July 1861. Confederate forces near Manassas Junction were reinforced by troops moved rapidly by rail from the Shenandoah Valley via the Manassas Gap Railroad. They arrived in time to help thwart and defeat Union forces attempting to gain control of the junction.

When Confederate forces gave up their advanced positions in the spring of 1862 and retreated to more defensible ground in Virginia’s interior, they lost control of the Manassas Gap Railroad. The fortunes of the Shenandoah Valley thereafter mirrored the railroad’s fortunes. The line changed hands depending on which army was advancing and which army was retreating. Sections of the line were scavenged for rails to be used in more vital places, and the rolling stock was similarly dispersed. By mid-1863, the line was overgrown with weeds and was so slippery that a locomotive couldn’t get enough traction to pull cars. When the war ended, pretty much all that remained was the railroad bed. The Orange & Alexandria was similarly battered. The two crippled companies merged to form the Orange, Alexandria & Manassas Railroad. The Independent Line, already moribund for years, was now rendered completely superfluous.

The very evident footprint of the Independent Line still lingers to this day, especially where it runs—carefully preserved—through Manassas National Battlefield Park. The path of the line is still occasionally visible in other spots, appearing and disappearing, depending on the paths of modern highways and the density of development generally. Parts of the right of way in Fairfax County appear enigmatically on present-day tax maps, with the peculiar shapes of some property lines reflecting the route of the old railroad bed. The massive stone abutments for the never-completed bridges over Cub Run and Bull Run still stand like majestic monuments, abandoned in the woods north

of the battlefield. Several miles east of the Manassas battlefield, the railroad bed skirts the southern edge of the Chantilly, or Ox Hill, battlefield.

The Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad was thus fated to figure prominently in the war’s history. As a financial undertaking and railroad venture, it was never of any account at all.

Earl McElfresh is the principal of McElfresh Map Company and author of Maps and Mapmakers of the Civil War.