In 1907, a monument honoring Union Maj. Gen. George Sears Greene was dedicated on Culp’s Hill at the Gettysburg National Military Park. It was on that ground that Greene and his New York brigade had secured the northern end of the Army of the Potomac’s fishhook battle line at a critical point of the July 1863 battle. Although the Little Round Top stand by Colonel Joshua Chamberlain and the 20th Maine tends to receive more credit for the Federal victory at Gettysburg, Greene’s actions on Culp’s Hill on July 2-3 were just as important—maybe more so.

Speaking at the Culp’s Hill dedication, Colonel William F. Fox paid tribute to the general’s leadership and the trademark tenacious fighting spirit of his men not just at Gettysburg but throughout the war. “Greene’s division [at Antietam] was not only actively engaged, but made a record for hard fighting, good generalship, and effective service that has received favorable mention from every historian of that famous field,” recalled Fox, a Civil War veteran and author of the three-volume New York at Gettysburg and Henry Slocum and His Men. “General Greene has become so well known by reason of his brilliant achievement at Gettysburg that there is a tendency to overlook or forget the good work accomplished by him and his division at Antietam.”

What Fox intimated that day at Culp’s Hill remains true. There is a regrettable propensity to overlook or forget altogether the accomplishments of George Greene and his men at Antietam on September 17, 1862—nine months prior to Gettysburg.

Born May 6, 1801, in the small village of Apponaug, R.I., George Sears Greene was an 1823 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy and remained at West Point as an assistant professor until reassigned in 1827. After service at posts such as Fort Sullivan in Maine—where in 1833 his wife of five years and three children died of disease—Greene resigned from the Army in 1836 to be a civilian engineer. When the opening shots of the Civil War were fired in April 1861, he was busy aiding in the construction of improvements and enlargements to the Receiving Reservoir of the Croton Aqueduct in New York’s Central Park.

With a need for seasoned military officers, Greene readily offered his services to the Union. The governors of both New York and Massachusetts offered him command of a state regiment, and in January 1862, he became the colonel of the 60th New York Infantry. Three months later, he was promoted to brigadier general, and held brigade command that summer. By the start of the Maryland Campaign in the fall of 1862, Greene was in command of the 2nd Division of the 12th Corps, led by Greene’s West Point classmate, Maj. Gen. Joseph K. Mansfield.

The corps numbered a little more than 7,200 men—with only two divisions the smallest of all Union corps at Antietam. Its composition was a snapshot of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac: Both hardened veterans and green troops, all under the guise of mostly inexperienced and sometimes questionable leadership (Mansfield himself had taken command only days before what turned out to be the bloodiest one-day battle in American history). Yet at Antietam, the 12th Corps redeemed itself after what had been thus far a difficult year of battlefield setbacks.

In the wake of the Army of Northern Virginia’s August 1862 victory at Second Manassas, which spurred General Robert E. Lee’s decision to carry the war north, Lee was forced to divide his army after reaching the vicinity of Frederick, Md., in early September. Lee issued an operational plan, Special Orders No. 191, informing his commanders how he was going to divide his army across the Maryland countryside. It was this plan, found by Union soldiers on September 13, that provided Union commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan the information he needed to catch and bring to battle Lee’s scattered army.

After the two sides exchanged victories, first the Federals at the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, and then the Confederates at Harpers Ferry the following day, both armies converged on the small western Maryland town of Sharpsburg.

Mansfield’s 12th Corps deployed after a short, sharp skirmish on the evening of September 16 between Brig. Gen. George G. Meade’s Pennsylvania Reserves in Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s 1st Corps and John Bell Hood’s Division in Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s Right Wing. Throughout the late hours that night and into the early hours of the 17th, Mansfield’s men crossed Antietam Creek by way of the Upper Bridge to move into position to support Hooker as needed.

Greene, elevated to division command shortly before the Maryland Campaign, had his three brigades at Antietam: Lt. Col. Hector Tyndale commanded the 1st Brigade; Colonel Henry Stainrook, who would survive Antietam but fall at Chancellorsville in May 1863, was in charge of the 2nd; and Colonel William B. Goodrich, a journalist and newspaper publisher, commanded the division’s 3rd Brigade.

In the early morning hours of September 17, Hooker’s corps occupied the North Woods and East Woods on the Joseph Poffenberger Farm, with Greene and the rest of the 12th Corps west of the creek and spread out across the Hoffman and Line farms. By 2:30 a.m., more than 15,000 Federal troops lay on their arms in the dark and rain. To make the situation worse, Private J. Porter Howard of the 111th Pennsylvania Infantry later wrote, “[T]he field that we lay in that night, for there had been manure spread over it and not a very nice place to sleep on.”

The men on both sides woke to a heavy, low-lying fog covering the countryside. It was in those moments, just as it started to get light, that the first shots of the Battle of Antietam were fired by Confederate artillery. The rounds fell within the Union lines on the Poffenberger Farm and very quickly more cannon fire thundered across the landscape. The first small-arms fire came from around the Mumma Cemetery, about a half-mile south of the North Woods. It was this activity that caused Hooker to start his initial assault. For the next two hours, the combatants traded control of the East Woods and farmer David R. Miller’s cornfield. The sounds of battle that morning are also what alerted Mansfield that the engagement was under way. He started his corps toward the field.

The other division commander in the 12th Corps was Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams. His men led the way through the farm of Joseph Poffenberger’s cousin, Samuel. Their push south was made more difficult by concentrated Confederate cannon fire from Colonel Stephen D. Lee’s Reserve Artillery Battalion posted on a ridge east of the Dunker Church. This was the first time that five of the regiments in Mansfield’s corps had ever experienced combat. While attempting to get one of these new regiments to close in and assist in Williams’ attack, the 59-year-old Mansfield was mortally wounded. He was the second of six generals to be killed or mortally wounded during the battle—Confederate Brig. Gen. William E. Starke was the first, dying within an hour after being mortally wounded during the early morning fighting on September 17. (Mansfield would die September 18.)

Following the loss of Mansfield, command of the corps fell to Williams. It was the arrival of his division that stopped the Confederate advance along the northern edge of the Cornfield as well as the East Woods. After taking command, Williams found Greene near the northern part of the East Woods. He directed him to send Goodrich’s brigade to the right and assist the scattered 1st Corps survivors near the Hagerstown Pike.

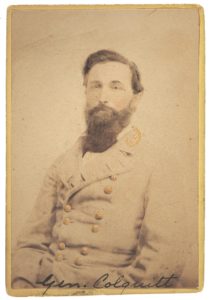

As confusion in the command and deployment of the 12th Corps unfolded, Confederate reinforcements from Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill’s Division moved across the Mumma Farm toward the Cornfield. Three of Hill’s five brigades were sent north, among them Brig. Gen. Gabriel Rains’ old brigade, now commanded by Colonel Alfred Colquitt. Hill’s other two brigades remained in the Sunken Road.

Due to the disposition of Williams’ Division, Colquitt’s line ran to the northeast, through the Cornfield. The 13th Alabama was on the far left, followed to the right by the 28th Georgia, 23rd Georgia, 27th Georgia, and finally the 6th Georgia on the far right along the northern fence of the Cornfield, extending partially into the East Woods. The brigade numbered roughly 1,320 soldiers. Moving toward them through the East Woods were Greene’s two brigades, a little more than 1,700 men.

In the advance, Tyndale’s three Ohio regiments, not more than 425 men total, formed on the right of the large but untested 28th Pennsylvania. Before moving into battle, discussion arose on whether command would proceed more smoothly if the Ohio regimental colors were at the center of the three regiments in one cluster. The men, however, preferred to fight under their individual banners.

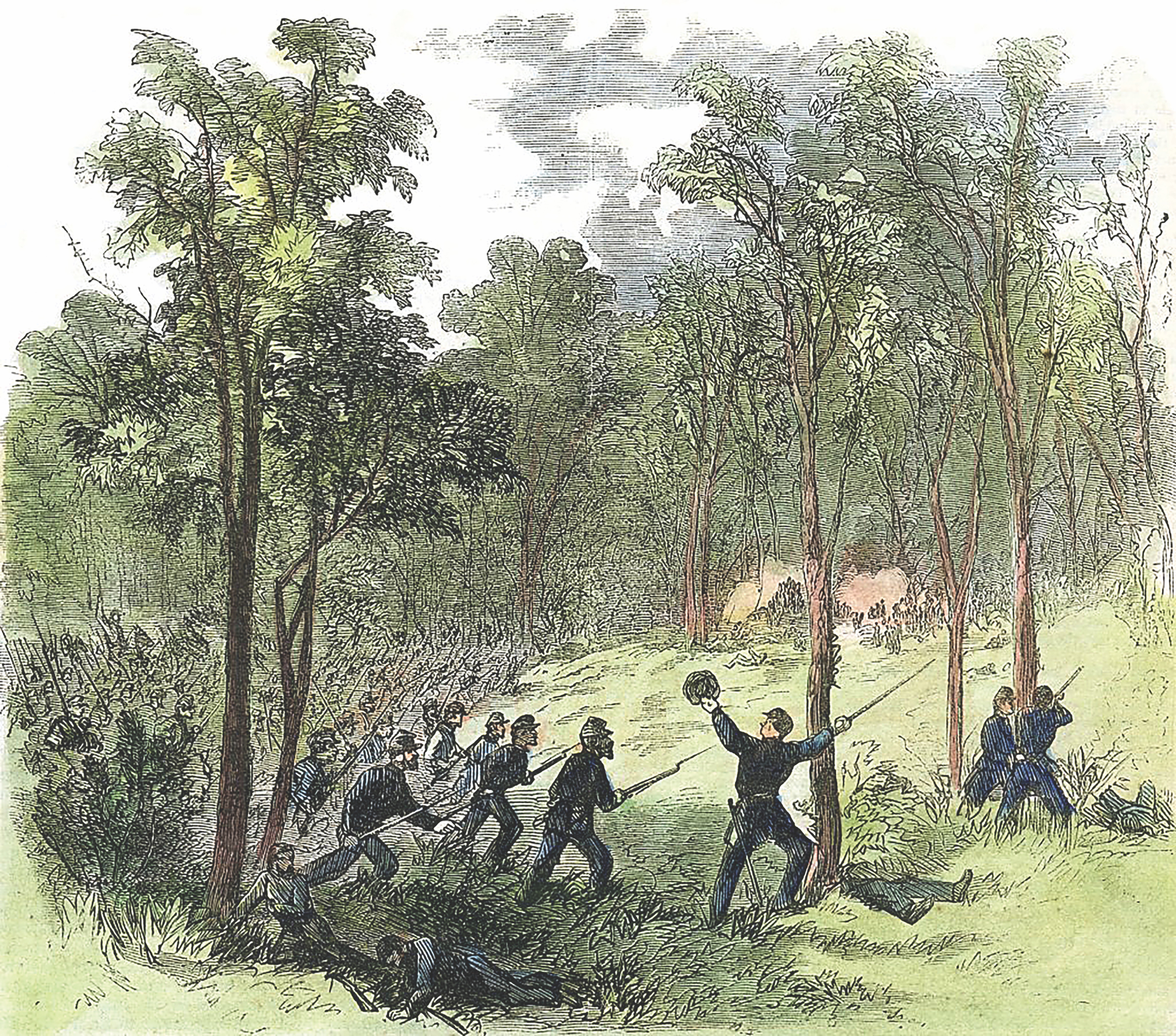

At approximately 8:15 a.m., Tyndale moved toward Colquitt’s line. Lieutenant Colonel Eugene Powell, commander of the 66th Ohio, remembered “mist and fog of the early morning rendered everything obscure and uncertain; but peering through that cloud of vapor, I saw a line of enemy standing in the open space just beyond and behind a rail fence.”

The men he saw were the troops of the 6th Georgia, commanded by Lt. Col. James M. Newton. Powell ordered his Buckeyes to fire. But just as that order was given, Major Orrin Crane of the 7th Ohio interjected, believing they weren’t enemy troops. When it was clear that Powell was correct, the men quickly leveled their weapons and fired.

Newton and Captain John Hanna were killed in the initial volley. The 28th Pennsylvania then closed in on the right, adding to the Georgians’ consternation. A desperate hand-to-hand melee broke out.

“[W]e were exposed to a fire from all sides and nearly surrounded,” Colquitt noted in his after-action report. “….the enemy closed upon our right so near that the ranks were scarcely distinguishable.” The 6th Georgia was hammered in the initial onslaught. The 27th Georgia, its right flank exposed, fell back, as did the 23rd Georgia, 28th Georgia, and 13th Alabama in turn.

Stainrook’s men moved in on the left of the 28th Pennsylvania and forced three regiments from three Confederate brigades out of the East Woods toward the Dunker Church. Near the intersection of the Smoketown Road and the Hagerstown Pike, Generals D.H. Hill, John Bell Hood, and Stonewall Jackson tried to rally the shattered lines, with little success.

Greene’s men pushed south through the corn and the East Woods, slowed a bit by the final shots of S.D. Lee’s artillery before the Rebel gunners fell back to resupply. Those guns, Sergeant William Fithian of the 28th Pennsylvania recalled, had “complete range upon us, creating sad havoc among our brave fellows. They fell right and left; some with heads blown off others with legs, arms and so on.” Eventually, the Federals crossed fences along the Smoketown Road and headed into a swale west of the Mumma Farm that afforded some protection. Having exhausted their ammunition, they needed to be resupplied.

Now about 9 a.m., a brief lull fell across the battlefield. Compared with their counterparts, Greene’s men had suffered few casualties. On the other hand, Colquitt’s Brigade had lost 55 percent of its strength. The 6th Georgia’s loss was nearly 90 percent—Company E, which entered the fight with 33 men, had 13 killed, 17 wounded, and three captured.

At 9:15 a.m., Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s 5,300-man 2nd Division in the 2nd Corps, advanced toward the West Woods. Greene saw Sedgwick’s men marching on his right, on the south side of the Smoketown Road, northwest of the Mumma Farm. Because of the ridge the road traversed, and with Greene’s men re-forming in the swale, Sedgwick’s line quickly disappeared from view. Suddenly, Confederate reinforcements slammed into the Federal troops in the West Woods and behind the Dunker Church, with 2,200 of Sedgwick’s 5,300 men killed or wounded in barely 20 minutes. Because of the terrain—the ridge in particular, which had afforded Greene’s men protection moments before—Greene could not see Sedgwick’s survivors driven back toward the North and East Woods.

If there was a point during the battle when fighting occurred up and down the entire line, it was about 10 a.m. Federal attacks on Burnside Bridge to the south were under way; Union forces were making their initial assaults on the Sunken Road; and the Confederates were driving Sedgwick’s men from the West Woods. In the center, meanwhile, activity was about to begin again for Greene’s division.

As Greene’s men were being resupplied with ammunition, two batteries were sent forward to assist the Union troops near the church, only to be driven back in short order. Then Captain John Tompkins and his six rifled guns of Battery A, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery moved to replace them, unlimbering farther south than the position recently vacated by Battery D under Captain Albert Monroe. Greene, on the left of his line, started to push up and out of the swale, with Tompkins to his left. The Hagerstown Pike, the Dunker Church, and the West Woods became visible just as his men gained the crest. Confederate activity in the West Woods was apparent.

Brigadier General Joseph Kershaw’s South Carolina brigade was in the midst of a Confederate counterattack in the West Woods. His four Palmetto State regiments struck the far left of Sedgwick’s line in the woods behind the church. Kershaw was able to stop three of his four regiments from pressing the Federals too far across the pike toward the East Woods. These three regiments—the 2nd, 7th, and 8th South Carolina—were the men noticed by Greene’s troops.

In his official report, Major Crane wrote: “We then received orders to fall back under cover of the hill and await the advance of the enemy. When within short range, our troops were quickly advanced to the top of the hill where we poured into their advancing columns volley after volley. So terrific was the fire of our men that the enemy fell like grass before the mower.” As the Federals crested the ridge, Tyndale’s men were on the right and Stainrook’s—the 111th Pennsylvania, 3rd Maryland, and 102nd New York—farther south.

After driving back Kershaw’s Brigade, Greene’s men had little time to breathe before another Confederate attack, this by three regiments of Colonel Van H. Manning’s Brigade, part of Brig. Gen. John Walker’s Division in Longstreet’s Wing. Manning’s men were split as they attempted to connect with D.H. Hill’s Division in the Sunken Road and Jackson’s weary troops to the north. Posted on the high ground west of the Hagerstown Pike, just north of the Sunken Road, the 3rd Arkansas and 27th North Carolina were left to make this connection. The remaining regiments—from left to right, the 46th North Carolina, 30th Virginia, and 48th North Carolina—advanced toward Greene just as Kershaw’s men fell back.

After crossing fences to their front, they were ordered to charge up the elevation, only to meet the same galling fire that had mowed down Kershaw’s men before them. The 30th Virginia alone suffered 105 casualties out of 236 men engaged, with 49 killed.

The Federals pursued the disconcerted Confederates, making their way across the Hagerstown Pike by way of a hole in the fence and eventually taking up an arc-shaped position behind the Dunker Church. At this point, 10:30 a.m., Greene mistakenly believed Sedgwick was still on his right in the West Woods. For the next two hours, Greene and about 1,300 troops maintained their exposed position, aided by a few regiments from other units as well as two artillery pieces of Captain Joseph M. Knap’s Battery E, Pennsylvania Light Artillery.

The section of artillery sent to Greene was originally posted east of the pike, opposite the church. Shortly after unlimbering, Tyndale, who already had three horses shot from under him that day, directed Lieutenant James McGill to move his guns to help stop fire coming from the 3rd Arkansas and 27th North Carolina. “I made earnest protest,” McGill recalled, “stating among other reasons, the guns could be easily captured if a charge should be made and any of the horses shot.”

As that unfolded, men on the right in the 13th New Jersey realized a problem of their own. Although Colonel Ezra Carman had been told the contrary upon moving into position, he was so certain there were no Federals to his right that he sent a messenger to Greene to inform the general that the 13th was the end of the line. Greene personally rode to confer with Carman and, after a quick reconnoiter, advised the colonel not to worry—that Sedgwick’s men were on his flank and there were more pressing issues on the Federal left. Not long after Greene departed, however, Confederate skirmishers began moving against the 13th New Jersey and 28th Pennsylvania, though quickly driven back.

Back on the far left, McGill’s two guns had arrived. One sat in the middle of the Hagerstown Pike, the other pushed into the woods. As he waited for orders on which direction to fire, McGill’s fears came to fruition. The 3rd Arkansas and 27th North Carolina charged through the cornfield along their front. Four men were wounded, two horses shot, and one gun had to be left behind after being pinned under a fallen tree limb. According to McGill, that piece and two caissons were saved from capture only because of the gun he’d placed on the pike. The left of Greene’s line, however, began to buckle under the weight of this attack.

About the same time, the Confederates launched an attack on the right. The Federal and Rebel soldiers did not know who was where in the West Woods, as undulating terrain and rock outcroppings affected visibility. With officers from the 49th North Carolina and 13th New Jersey out in front of their lines gathering information, combatants in the opposing regiments suddenly realized the situation and began firing simultaneously.

Greene could hold on only for so long. With both his flanks under attack, the lone option was to fall back. At about 12:15 p.m. the Federals began withdrawing from the West Woods, putting up some resistance as they fell back toward the East Woods. It was during this action that Tyndale was shot, receiving a compound fracture of his skull. He was dragged off the field and would survive. A combination of artillery and infantry fire finally halted the Confederate counterattack.

Now a little after 1 p.m., another lull fell over the battlefield. As was already the case for the 1st and 2nd Corps, as well as all the Confederate forces on the northern end of the field, the 12th Corps’ day was over. Combined, the casualty number was about 16,000 stretching from the Sunken Road to the North Woods and there was still more fighting to come south of Sharpsburg.

Although not as widely known as other actions at Antietam, the advance of Greene’s soldiers was the farthest and longest sustained push into the Army of Northern Virginia’s lines on this bloody day. In April 1863, Greene, likely already realizing his men’s actions at Antietam were being overlooked, wrote: “I still think there were some persons who were aware of our presence on that day if the commanding general was not and that we unmistakably left our work on that field.”

[hr]

After the Army of Northern Virginia retreated across the Potomac River on September 18-19, 1862, Union burial parties began interring the Federal dead on the Antietam battlefield before tending to the Confederate dead. Long trenches were the preferred method for burying those bodies, and every piece of soft ground became a welcome spot for graves. Soldiers would be buried in nearly every farm field within miles of Sharpsburg.

In 1864, local farmers complained to the state government that they were unable to properly plow the fields that were now serving as makeshift graveyards. That led to the purchase of land just east of Sharpsburg to be used for a cemetery.

Only Union soldiers were reinterred when the Antietam National Cemetery opened in 1867, which meant the Confederate dead remained undisturbed in place for the next half-dozen years or so. Eventually, many of the Rebel deceased were reinterred at Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown, Md. Those two cemeteries would hold more than 6,000 reinterred bodies mostly from the battlefield.

In the spring of 2020, a research team from the Adams County (Pa.) Historical Society stumbled upon a unique find while searching the holdings of the New York Public Library for a known map of Gettysburg. The map they found, crafted by California-based cartographer Simon G. Elliott, did not show the Gettysburg battlefield, as expected but did document the burial locations of more than 5,800 soldiers on the Antietam battlefield.

Until then, park rangers and historians were confident they knew where the Antietam deceased had been buried. Using sketches by artist Frank Schnell, and photographs taken by Alexander Gardner and James Gibson days after the battle, historians typically could point to an area of the field and prove that soldiers were, at one point, buried in a specific location.

According to a database compiled after digital analysis of the original document, there were approximately 5,844 identified graves on the battlefield: 2,634 Union and 3,210 Confederate. In addition, 50 individual soldiers, representing both armies, were identified on the map along with 40 locations where 269 horses killed during the fighting were gathered to be burned.

It is unfortunate that because a small portion on the right side of the map is missing and that a few other areas are illegible, an exact count of the graves cannot be confirmed. Also, minor mistakes were made. The 1st Minnesota Infantry was part of Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s 2nd Division, which fought in the West Woods. As they reached the far northwestern corner of the woods, they were met by Confederate small-arms and artillery fire from a ridge just a few hundred yards to their front.

On Elliott’s map, in the section of the woods where the 1st Minnesota fought, three graves are identified as 1st Maryland. Since no 1st Maryland Infantry fought at Antietam, these were clearly 1st Minnesota soldiers. Also, in this section of the map, a lone Union gravesite bears the name “O.L. Cornman, 1st Md.”

Because a Corporal Oscar Cornman did fight for the 1st Minnesota, this is undoubtedly his gravesite. Further proof can be found in the September 30, 1862, Stillwater (Minn.) Messenger: “Corporal Cornman’s body was interred by company B, apart from all others, in a beautiful grove near the battlefield. May it rest undisturbed by the clangor of battle until the great day when kindred and friends and comrades shall meet to separate no more forever.” Cornman’s remains were among those reinterred in the Antietam National Cemetery.

A few other graves on the map have a George Greene connection. The 111th Pennsylvania, of Henry Stainrook’s brigade, swept through the East Woods and passed the Mumma Farm before taking up position south of the Dunker Church. At some point during the battle, Corporal John S. Good was wounded and taken to a field hospital, where he later died. His grave is singled out on the map near the Samuel Poffenberger Farm, just northeast of the East Woods.

Also of note is Alexander Gardner’s famed photo, “A Lone Grave on the Battlefield of Antietam,” which photo expert William Frassanito determined in his 1978 book Antietam: A Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day was that of Private John Marshall of the 28th Pennsylvania, part of Lt. Col. Hector Tyndale’s brigade in Greene’s division. The Elliott Map confirms that Frassanito’s assessment was correct.

A grouping of 10 graves of soldiers from the 27th North Carolina Infantry on the far northeastern corner of the Elliott Map, near the Smith Farm, is also significant. After advancing toward the Mumma and Roulette farms, the 27th, along with the 3rd Arkansas, took part in the attack that drove Greene’s division from the West Woods about 12:30 p.m.—before retreating itself. Because the burial location is more than a mile from where these men fought and behind enemy lines, it is likely these Tar Heels were wounded, left on the field, and then taken to a Union field hospital. Evidently, they had died and were buried where very few other Confederate graves were marked. One grave is specifically identified as that of Lt. R.L. Noble, 27 N.C.

The Elliott Map has given us some valuable added context about the cavalcade of Antietam casualties that bloody September day. –B.B.

Brian Baracz, a native of Cleveland, Ohio, has worked as a park ranger at Antietam National Battlefield since 2000. He lives in Frederick, Md.