Once Italy surrendered to the Allies in September 1943, the Germans moved into the vacuum. Rome was declared an “open city” by the Italian government, meaning it was unoccupied and off limits to attack, but Germany rushed in troops for an occupation that lasted for nine months and subjected the citizens to the brutality of Nazi rule for the first time in the war. The Nazis rounded up Jews and sent them to their deaths in concentration camps, violently enforced curfews, and attempted to crush any opposition.

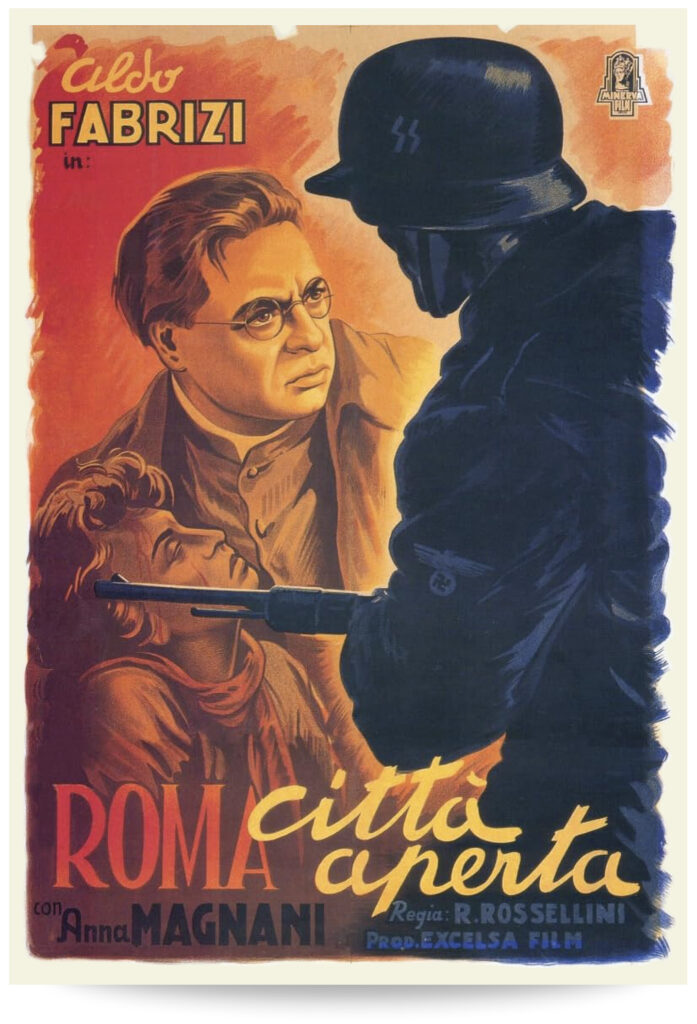

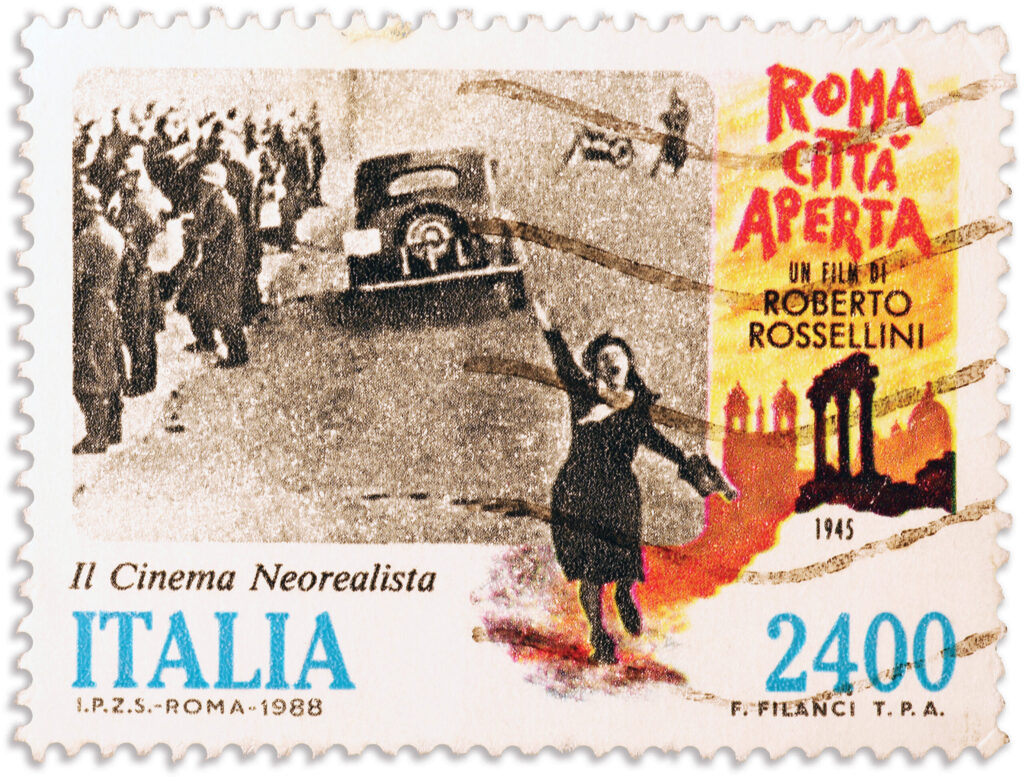

A story about Italian resistance to German occupation, Roberto Rossellini’s 1945 film Roma città aperta (Rome, Open City) is recognized as the first classic film of what has become known as the neorealist movement. Shot in the city after the Germans had left but before the war was over, the stark black-and-white film remains powerful even as it nears its 80th anniversary. Wrote novelist Virginia Baily for The Guardian newspaper in 2015, “It was one of the most visceral, gut-wrenching cinematic experiences of my life and I have carried images and sounds from it—the old ladies stalling the Gestapo while the resistance hero escapes across the roofs, the martial music playing as the German regiment marches down a deserted street, the tortured hero slumped in a chair, the priest in his black robes—with me ever since.”

The film opens as those German soldiers march through Rome to make a nighttime raid on a downtrodden apartment building. They seek Giorgio Manfredi (Marcello Pagliero), a communist and a central figure in the resistance. The apartment dwellers do what they can to divert the soldiers, and Manfredi escapes across the rooftops. While the Germans search, they intercept a call on the communal telephone from Manfredi’s sometime mistress, Marina (Maria Michi), an actress who quickly hangs up when she realizes something is amiss.

One of the building’s residents is Pina (Anna Magnani), a plain-speaking widow with a son, Marcello. She is pregnant, and on the night the Germans arrive she is planning to get married the next day to Francesco (Francesco Grandjacquet), a soft-spoken printer. Her spiritual adviser is the priest Don Pietro Pellegrini (Aldo Fabrizi), who also serves as a central figure in the resistance.

In the meantime, the German Major Bergmann (Harry Feist) plots with the manipulative Ingrid (Giovanna Galletti) to stamp out the resistance and capture Manfredi. On Bergmann’s orders the Germans conduct another raid on the apartment building. This time they herd all the residents outside. When Don Pietro hears that one of the children from the building has a hidden stash of bombs and guns, he bluffs his way inside under the guise of giving last rites to a bedridden old man. He manages to hide the weapons before the Germans find them.

Outside, Pina sees the Germans taking away Francesco. Frantic, she breaks free, and dashes down the street in pursuit of the truck carrying away her fiancé. The merciless Germans gun her down as her son watches. She dies in the street, cradled by Don Pietro. Partisans attack the truck convoy with the prisoners and Francesco manages to escape.

Bergmann and Ingrid have another tool they can use to find Manfredi: Marina. The cynical actress, angry with Manfredi and addicted to her creature comforts—which include drugs that Ingrid provides her—tells the Germans where they can find the resistance leader. The Germans descend as Manfredi and Don Pietro are bringing an Austrian deserter to safety and arrest the three men on the street. Bergmann forces the priest to watch as he has Manfredi brutally tortured, but neither the communist nor the Catholic priest divulge any information. Manfredi dies during his ordeal and Bergmann has the priest executed. Tied to a chair and praying for God to forgive his executioners, Don Pietro is murdered while the children from the apartment look on, horrified, before they trudge back into town, damaged in ways we can only imagine.

Rome, Open City was something of a change of direction for director Rossellini, who earlier in the war had made films for producer Vittorio Mussolini, the son of Il Duce. Even before the Germans had been forced out of Rome, Rossellini had begun thinking about making a movie about the resistance. He wanted “to show things exactly as they were,” he said. One of his collaborators on the story was another up-and-coming Italian filmmaker named Federico Fellini. Rossellini shot the film with little money, on location, and with film stock he scrounged—or even stole—from whatever sources were at hand, including cast-off snippets from other photographers. (The director said he stole stock from the offices of the U.S. Army’s Stars and Stripes news organization.) Most of the actors he used (with the notable exceptions of Magnani and Fabrizi) were nonprofessionals. He even used German prisoners-of-war as extras, including the soldier Pina slaps before making her ill-fated break. The result was a fiction film that looked and felt more like a documentary—in fact, the distributor Rossellini had obtained reneged on the deal, saying Rome, Open City wasn’t a “real movie.” But the film found a distributor in the United States and became a success, launching Rossellini’s international career and putting Italian neorealism—a genre embraced by other directors like Luchino Visconti and Vittorio de Sica—on the cinematic map.