In the early morning hours of April 2, 1865, a collection of Vermont soldiers and Rhode Island artillerymen performed what was aptly remembered as “one of the most perilous exploits of the war.” During the Union assault at Petersburg, Va., the New Englanders captured two Confederate howitzers and, as the battle raged around them, reversed the guns and began firing at the Rebels. For their contributions in the eventual Union victory that broke the Confederate lines around Richmond, leading to Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox one week later, seven members of the battery and two Vermonters received Medals of Honor.

Representing the Ocean State in this daunting mission was Battery G of the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery. No surprise, as artillerymen from Rhode Island were regarded by many as the best in the Union Army. The nation’s smallest state would, in fact, send 10 batteries to the front during the war, all of them trained by the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery, a militia organization dating back to 1801. Battery G was mustered in in the fall of 1861, the unit an amalgamation of Yankees from the rural parts of Rhode Island, the sons of the business elite from Providence, and Irish and German immigrants.

First engaged at Yorktown, Va., in April 1862, as part of the 2nd Corps, the battery would fight at Fair Oaks on the Virginia Peninsula and in the subsequent Seven Days’ Battles. At Antietam in September 1862, its guns were heavily engaged at the Dunker Church and in the Bloody Lane and were again in the fray that December at Fredericksburg. In May 1863, Battery G suffered severely during the fighting at Chancellorsville and, after being transferred to the 6th Corps, took part in a rear-guard action near Gettysburg in July.

Time to Strike

The following spring, the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, still attached to the 6th Corps, served prominently in the Overland Campaign, and in the fall was engaged in the Shenandoah Valley. Early in the clash at Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, the battery—now under the command of Captain George W. Adams, a tough, no-nonsense but respected combat veteran—was overrun. It would lose nine men killed and two guns before reinforcements helped produce a monumental Union victory.

After a winter spent reorganizing the unit, including consolidation with the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery’s Battery C, the refurbished Battery G arrived back at the Petersburg siege lines in February 1865. By late March, after the Army of the Potomac had spent nine grueling months besieging Richmond and Petersburg, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant sensed a potential breakthrough for his Union forces. Lee’s lines were stretched to the breaking point, as his 40,000 or so men tenuously defended a 40-mile front. With Confederate deserters pouring in each day, Grant felt it was time to strike.

His plan to capture Richmond and end the war was set in motion on March 29, as the Cavalry Corps and the 5th Corps swung to the left and on April 1 captured the strategic crossroads at Five Forks. Yet Grant, unable to flank Lee’s defenses, ordered a frontal assault by the Army of the Potomac on Petersburg itself, to begin at 4 a.m. April 2.

It was the task of Major Andrew Cowan’s 6th Corps’ Artillery Brigade to provide supporting fire for the assault. After receiving notice of the charge, Adams met with corps commander Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, offering a mission the captain had been considering since arriving in Petersburg. During a charge on the Confederate lines, infantrymen accompanied by select cannoneers would attempt to capture enemy artillery—guns that could then be used both to boost the assault and repel any Confederate counterattack. Adams’ remaining cannoneers in Battery G, meanwhile, would provide support with their own 3-inch Ordnance Rifles.

Before granting Adams permission, Wright “warned him of its extreme danger”; Adams, though, would not back down, finally receiving Wright’s consent. The captain would take only volunteers, however, fearing it was likely to be a costly assault. Stressing the mission’s extreme importance and danger, Adams said none who chose not to volunteer would be looked down upon. Every member of the battery stepped forward instantly, with 20 eventually selected.

Unlike the infantrymen, who were armed with muskets and bayonets, the cannoneers would carry only their friction-primers, sponge-rammers, lanyards, and artillery spikes, which, if the men faced trouble, could be pounded into the guns’ vents to render them inoperable.

“A short but desperate fight”

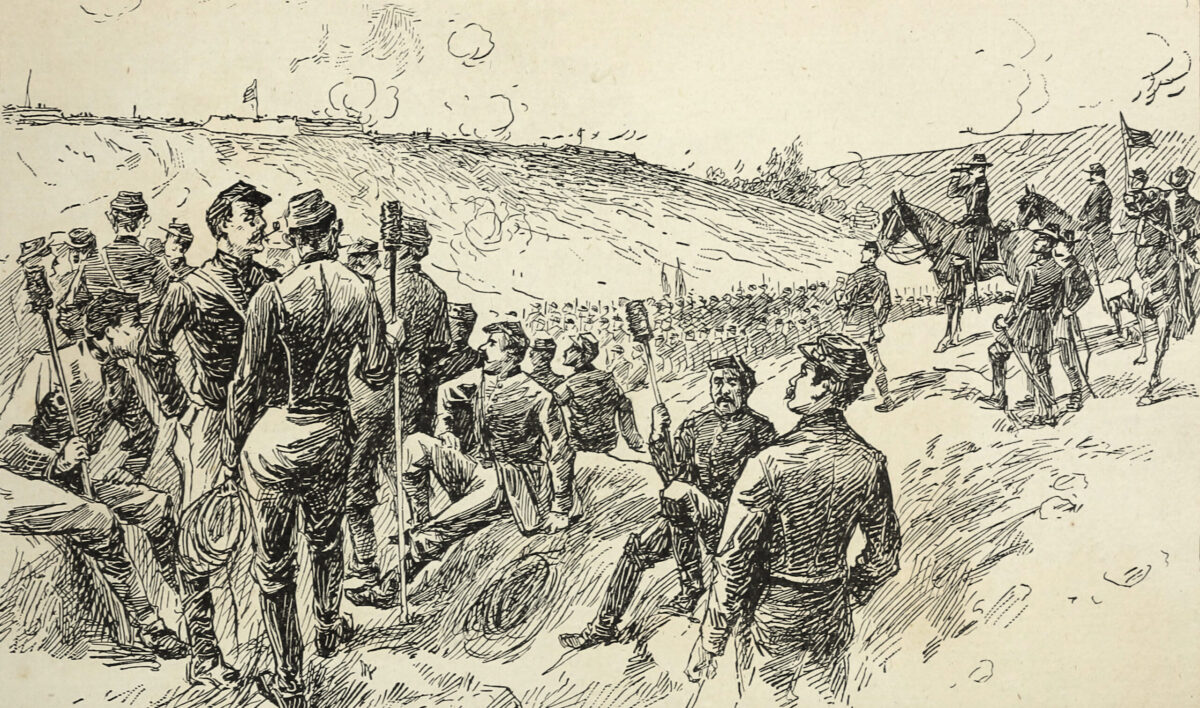

At 10 p.m. on April 1, all eight 6th Corps batteries launched a heavy bombardment on the Confederate defenses, which fortuitously masked the noise of the forming infantry. By midnight, the 6th Corps infantry had formed en masse in front of the Confederate works.

Axmen would lead the assault, cutting away defenses so the infantrymen could quickly exploit the breach. The soldiers were ordered to load but not cap their weapons, to prevent accidental firing. Silence was vital. The men were threatened with death if they spoke.

Adams’ detachment reported to Colonel Thomas W. Hyde’s 3rd Brigade, moving into position near Fort Welch. The 6th Corps formed in the shape of a spear, with Maj. Gen. Frank Wheaton’s 1st Division on the right, the 2nd at center, and the 3rd on the left—roughly 14,000 men total. Hyde’s brigade, in Wheaton’s center, was to swing left after entering the entrenchments to cut off the Boydton Plank Road and then the South Side Railroad. It was a moonless, misty night with a heavy ground fog hanging over the trenches—so thick that most soldiers couldn’t see 20 yards ahead. After 4 a.m. passed without a signal, as Grant waited for the fog to lift so the advancing columns would not be struck by friendly fire, Adams asked his men once more if any wanted to return to Battery G’s main position. Three did.

The first shot was finally fired at 4:40 a.m. by the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery’s Battery E on the corps’ extreme left. Immediately, every gun in the Army of the Potomac opened fire, including Battery G’s four pieces. Because of the cannonade’s immense noise, there was a 10-minute delay before the men realized the barrage had been the signal to advance.

Recorded Dr. George Stevens of the 77th New York: “Without wavering, through the darkness, the wedge which was to split the Confederacy was driven home.” Many of the 6th Corps’ batteries, however, fired only about a dozen rounds before stopping to avoid the “friendly fire” casualties Grant had feared.

As Hyde deployed his brigade, Adams and his men lost contact with the New Yorkers to their right and instead angled left, following Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Grant’s Old Vermont Brigade. The Vermonters rushed onward in total darkness, aiming for a 600-yard long ravine leading directly to an expected weak point in the Confederate line.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

As the Federals advanced, the Confederate defenses came alive. The Rebels, though poorly equipped, clearly had plenty of fight left in them. The guns Battery G had been sent to capture happened to be firing canister and were wrecking the Vermont lines. In merely 15 minutes, 1,100 6th Corps soldiers went down.

Regardless, the 17 Rhode Islanders pushed ahead, and within minutes Union infantry were scrambling into the Confederate forts, many firing a single volley and going in with bayonets. After crossing the deadly killing ground, the Rhode Island detachment angled for its prime destination, an earthen gun emplacement near a swamp in a woodlot. They promptly obeyed a “Capture that battery!” directive from the Vermonters.

Defending the line of earthworks around the fortification was a North Carolina brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. James H. Lane, who had positioned two 24-pounder howitzers at a vulnerable opening and another howitzer, two cannons, and an 8-inch mortar on the right of the ravine through which the Vermonters were charging.

Captain Charles Gould’s Company H, 5th Vermont, which had lost its way crossing no-man’s land during the initial bombardment, leaped into the redoubt, with 30 men following Gould for the cannons. A fervent hand-to-hand clash ensued.

Gould, who would receive a Medal of Honor for his actions, recalled it as “a short but desperate fight.” After the defenders abandoned the position, his unit quickly re-formed and pushed on.

Following directly behind Gould was Major William J. Sperry of the 6th Vermont. Upon seeing the two abandoned howitzers, he directed a dozen men to have the guns reversed and then fired at the fleeing Confederates. Some of his men and a few wayward members of the 11th Vermont were ordered to load the pieces, but Sperry, unable to locate friction primers, resorted to having his soldiers fire blanks into the cannons’ vents.

When the Battery G gunners arrived to find the Vermonters furiously working the howitzers, Sperry surrendered the position to Adams’ men. (The major later received a Medal of Honor as well.)

Some of Adams’ men had understandably worried the assault would inflict a high casualty count, but that was not the case. A ragged final volley by the scrambling North Carolinians did wound two cannoneers, however. Private Luther Cornell received a devastating right shoulder wound from a Minié ball, an injury from which he never recovered, and Private George W. Potter was blinded in the left eye.

Knowing a fierce struggle still lay ahead, Adams had little choice but to relieve his severely wounded cannoneers, ordering them to the rear. Cornell succeeded on his own, but Potter needed to be carried by two comrades. That left Adams with 13 men.

Victory and Recognition

At the South Side Railroad, the 6th Corps re-formed and swung left, capturing hundreds of prisoners while tearing up the tracks but also taking heavy losses as they pushed toward Hatcher’s Run. Nearly 50 Confederate guns would be captured, including a dozen in Battery G’s sector alone, but the remaining 13 Rhode Islanders could man only the two captured 24-pounder howitzers.

Union officers had trouble keeping their commands together, with their men, on the brink of victory, excited and energized. As the sun rose, however, the Confederates made a determined stand to hold their line and directed their fire at Battery G’s new position. Despite a hurricane of lead, the Rhode Island boys stood firm.

In the early morning light, with the unnerving cavalcade of shouting and Minié balls providing perhaps a perfect backdrop, the artillerists continued to load and fire their captured howitzers. The sustained fire and additional Union reinforcements finally pushed back the last remaining Confederate defenders.

The Rhode Islanders would fire nearly 100 rounds total during the brief engagement. According to one postwar account: “The men who served this gun so nobly, standing up unflinchingly before the terrific fire of the enemy were rewarded for their bravery and daring.”

Corporal Edward P. Adams was among the members of Battery G to be excluded from the assault force despite volunteering. He never forgot his comrades’ heroism, writing, “The Captain and his trained men with steady tread marched up with the Corps until the opportune moment when, rushing with great impetuosity they scaled the earthworks and crowned their undertaking with success….”

A good cross-section of the state was represented in what was labeled by one historian as “Adams’ intrepid band of cannoneers.” Sergeant Archibald Malbourne, a mill worker from West Greenwich, had recently transferred from Battery C, as had Sergeant John H. Havron, an Irish immigrant now living in Providence. Corporal James A. Barber was a fisherman from Westerly who joined in 1861 and was one of the few surviving Westerly Boys. Private John Corcoran was a machinist from Pawtucket who had served in Battery C. Private Charles D. Ennis came from a farm in Charlestown, while Corporal Samuel E. Lewis and the grievously wounded George W. Potter were from Coventry.

Adams nominated all 17 men who followed him into the “jaws of hell” for Medals of Honor, but trouble lay ahead. The commander had led 17 cannoneers into the assault, although only 13 were there to work the captured cannons after two were wounded and two others detailed to help those comrades to the rear. Adams never equivocated in establishing that all had been incredibly brave to volunteer.

In April 1866, the 17 Rhode Islanders were recognized with Medals of Honor, and in striking and engraving the 17 medals, the War Department did not differentiate among the names of those who had entered the fort and those who had gone to the rear—the citation on each reading: “For gallant conduct at Petersburg, VA., April 2, 1865. Being one of a detachment of twenty picked artillerymen who voluntarily accompanied an infantry assaulting column and who turned upon the enemy the guns captured in the assault.” Nevertheless, because of federal bureaucracy, only seven would receive theirs. The existence of the other 10 medals has been lost to history.

On June 20, 1866, four medals were delivered to Rhode Island for Sergeants Malbourne and Havron and for Corporals Barber and Lewis, the non-commissioned officers who had led the detachment in the action. There was no formal presentation; they arrived at the men’s homes in simple boxes along with a certificate announcing the award. Unfortunately, the officer in charge of the process failed to mail them to the privates who had also been recognized.

Potter, Corcoran, and Ennis received theirs in 1886, 1887, and 1892, respectively. When Adams inquired why the Medal of Honor had not been awarded to all at an earlier occasion, he received a nonplussed response: “It is possible that these soldiers have been overlooked, this particular service having been performed so near the close of the war.”

Adams already had a brevet of major for his heroism at Cedar Creek. Instead of receiving the Medal of Honor for planning and executing the mission, he was rewarded with brevets of lieutenant colonel and colonel. He wasted no time in sewing his eagles to his uniform, but his pay grade remained at the rank of captain.

The Battery G men took part in the pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia to Appomattox and were then mustered out in June 1865. Now part of Pamplin Historical Park near Petersburg, the site of Battery G’s charge remains one of the most decorated places in American military history.