Condemning slavery was a dangerous business in the 19th century. As a small, vocal, and growing group of Americans began to agitate in favor of abolition in the 1830s, they were often met with mob violence.

The attacks sometimes made headlines. William Lloyd Garrison was dragged through the streets of Boston by a mob in 1831, and preacher and newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy was shot and murdered during a shootout with an anti-abolition mob in 1837. The abolitionist-funded Pennsylvania Hall was burned to the ground by arsonists only days after it opened in 1838. For many abolition evangelists, however, violence and threats were merely a fact of life. In an 1840 letter to abolitionist leader Theodore Dwight Weld, one traveling lecturer noted an uptick in violence but remarked wearily, “I have not reported them to any of the papers because I am tired of [reading] about them….”

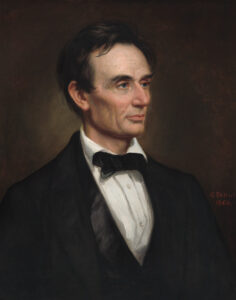

Abolitionists were quick to argue their traveling lecturers and newspapers should be protected by freedom of speech and the press guaranteed by the Constitution. That included Cassius Marcellus Clay, scion of one of the most influential slaveholding families in Kentucky, who had embraced abolitionism while studying at Yale. Although Clay supported a more gradual approach than radicals like Garrison, his politics generated many enemies in his home state. Undeterred, he began publishing an anti-slavery newspaper, True American, in Lexington in 1845.

When a group of men in Lexington met and demanded he cease publication, Clay responded with venom: “Go tell your secret conclave of cowardly assassins that C.M. Clay knows his rights and how to defend them.”

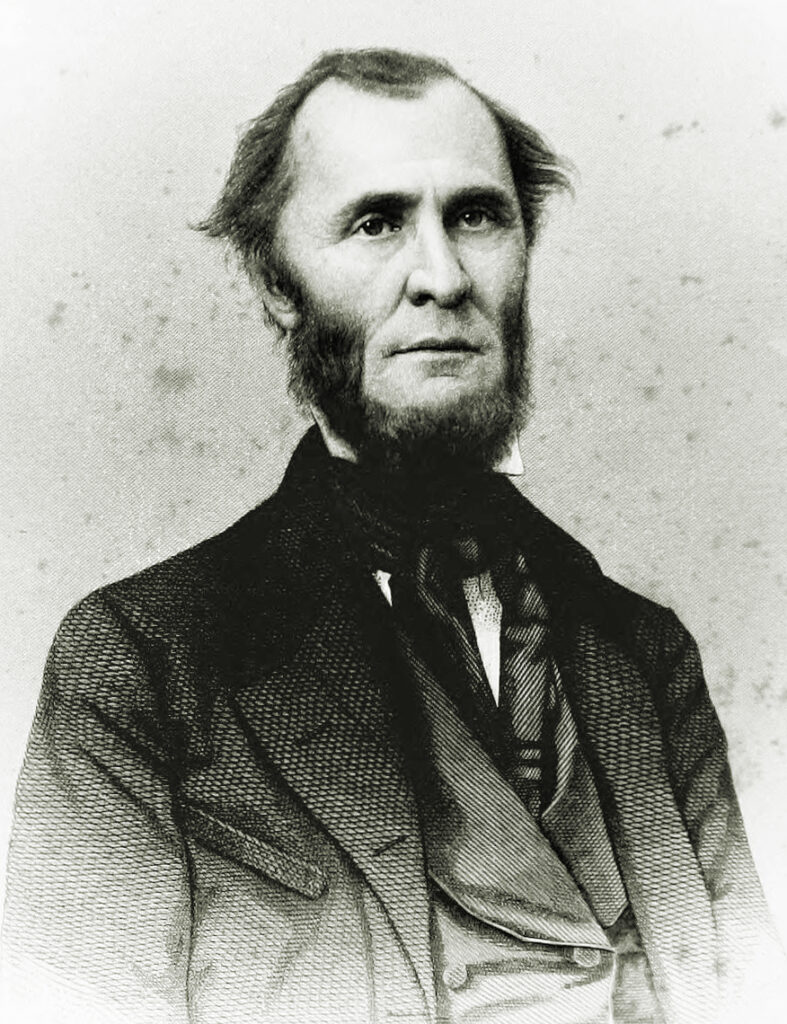

A second meeting, held two days later, would be attended by more than a thousand residents. Thomas F. Marshall, a local lawyer and nephew of former Chief Justice John Marshall, was asked to address the crowd and outline a legal pretext for shutting Clay down. Marshall offered a rousing, remarkably explicit justification for vigilante action against abolitionists. Though he could cite no specific law, Marshall succeded in giving the crowd’s planned suppression of Clay a veneer of legal legitimacy by highlighting the danger abolitionists supposedly posed to a slave society. The Lexington community, he argued, had an inalienable right to defend itself against Clay’s incendiary writing:

A formidable party has arisen within a few years in the United States….They aim at the Abolition of Slavery in America and halt not at the means. They are organized, active, united in pursuit of this object, and desperately fanatical. They have found their way into the National Legislature, and already exercise a threatening influence there. They command a powerful press in the United States. They have among them a burning zeal, commanding talent, and a large amount of political influence and monied capital….They maintain that the negro slave here is an American born, entitled to the full benefits and blessings of republican freedom, under the Declaration of Independence, which freed all of American birth. They maintain for him the right of insurrection and exhort him to its exercise.…

In proceeding by force and without judicial process, to arrest the action of a free citizen, to interfere in any degree with his private property, and if the necessity of the case and the desperation of the man require it, to proceed to extremities against his person, we owe it to our own fame, and the good name of our community, to set forth the facts upon which rises in our justification the highest of all laws, the law of self defense and preservation from great and manifest danger and injury.…

Such a man and such a course is no longer tolerable or consistent with the character or safety of this community. With the power of a press, with education, fortune, talent, sustained by a powerful party…who have made this bold experiment in Kentucky through him, the negroes might well, as we have strong reason to believe they do, look to him as a deliverer. On the frontier of slavery, with three free states fronting and touching us along a border of seven hundred miles, we are peculiarly exposed to the assaults of abolition. The plunder of our property, the kidnapping, stealing, and abduction of our slaves, is a light evil in comparison with planting a seminary of their infernal doctrines in the very heart of our domestic slave population. Communities may be endangered as well as single individuals. A great and impending danger over the life or personal safety of a single man, justifies the employment of his own force immediately in his own defense, and to any extent that may be necessary for his protection….

Our laws may punish when the offense shall have been consummated; but they have provided no remedial process by which it can be prevented. To war with [a newspaper] of Abolition by action or indictment for libel, would make that powerful party smile….An Abolition paper in a slave state is a nuisance of the most formidable character—a public nuisance—not a mere inconvenience, which may occasion delay in business or prove hurtful to health or comfort, but a blazing brand in the hand of an incendiary or madman, which may scatter ruin, conflagration, revolution, crime un-nameable, over everything dear in domestic life, sacred in religion, or respectable in modesty. Who shall say that the safety of a single individual is more important in the eye of the law than that of a whole people? Who shall say that when the case of danger—real danger, of great and irreparable injury to a whole community, really occurs—that it is not armed legally with the right of self defense?

….An unauthorized crowd, who inflict death upon persons or destruction upon property, for the gratification of passion or even for the punishment of crime, is a mob, and is the most fatal enemy to security and freedom. But as in the case of sudden invasion, or insurrection itself, the people have at once, independent of the magistrates, the right of defense, so when there be a well-grounded apprehension of great, and, it may be, irreparable injury, the use of force in the community is lawful and safe. We hold the abolitionists traitors to the constitution and the country, and enemies to the terms upon which the Union was originally formed, and the only terms upon which it can continue to subsist. When they bring their doctrines and their principles into the bosom of a slave state, they bring fire into a magazine. The “True American” is an abolition paper of the worst stamp! As such, the peace and safety of this community demand its instant and entire suppression.

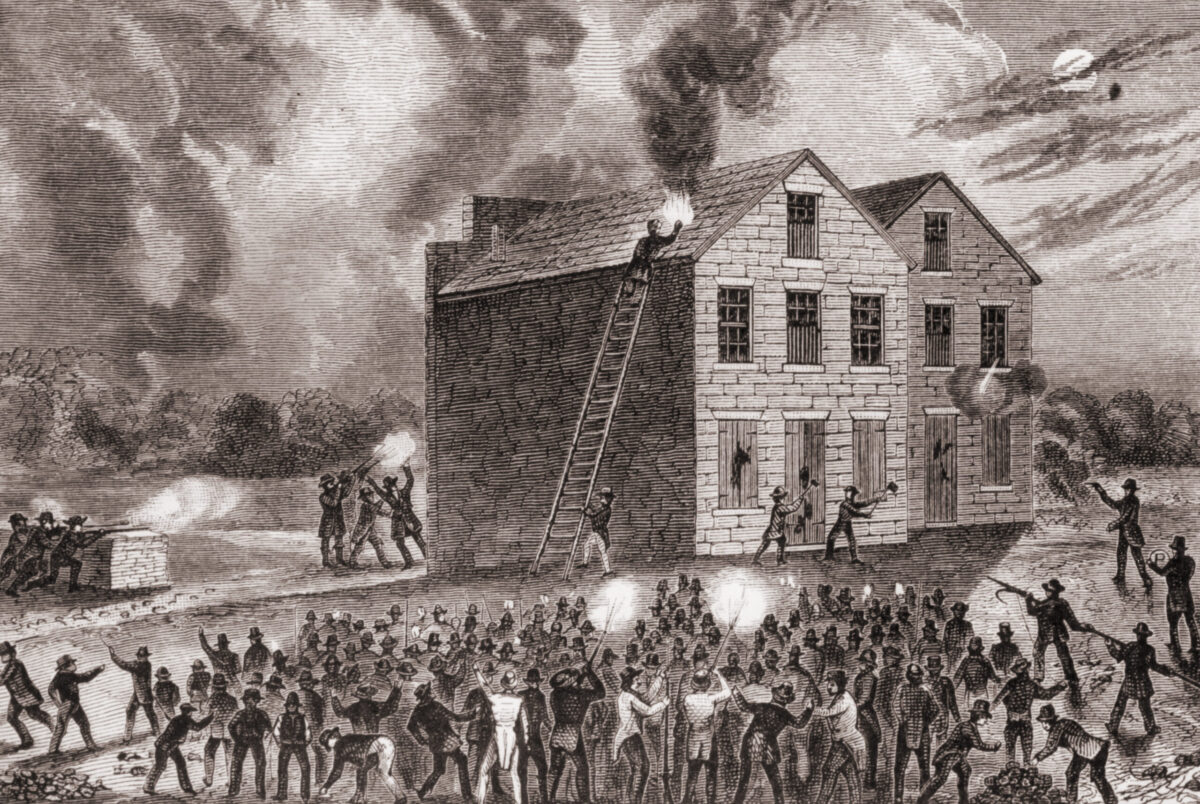

Inspired, the meeting adopted a series of resolutions condemning abolition and formed a committee to seize and ship the printing press and other items in the True American offices across the Ohio River to Cincinnati. Bedridden with typhoid fever, Clay was in no position to contest the seizure. His foes would also publish a pamphlet decrying his conduct and defending seizure of his press.

Upon recovery, Clay sought prosecution. Several committee leaders won cases defending their actions as lawful abatement of a public nuisance, arguing the True American was a danger to the community and its removal was justified to preserve public safety. In an 1847 trial against one ringleader in a neighboring county, however, Clay was awarded $2,500 in damages from a jury unconvinced that he needed to be silenced for the public good.