On the evening of Saturday, December 20, 1919, cold winds swept New York Harbor as 249 leftist radicals waited on Ellis Island to board USS Burford. The Army transport was to carry the deportees, most of whom were not American citizens, to Soviet Russia. The Soviet state formed after the overthrow of the czar in a 1917 revolution led by the Russian Social Democratic Workers’ Party, aka the Bolsheviks. Some deportees’ families, on hand to say goodbye, tried for one last moment with loved ones, but police officers pushed them back. Spectators included members of Congress, a crowd of journalists, and the youthful director of the U.S. Justice Department’s General Intelligence Division, also known as the Radical Division, John Edgar Hoover.

The event’s most famous deportee, Emma Goldman, was an anarchist, feminist, and advocate of free love. Unlike many of her companions, arrested the month before in raids Hoover had planned and executed, Goldman had been behind bars since 1918 for opposing United States participation in World War I and the draft. She also stood apart from the crowd on the wharf because she was a U.S. citizen, having immigrated from Russian-controlled Lithuania in 1885. Nonetheless, Hoover had dubbed Goldman “the Red Queen of Anarchy,” ordering her arrest under the 1918 Alien Act. She argued that citizenship precluded deportation, but Hoover persuaded fellow bureaucrats that because in 1908 the United States had revoked the citizenship of Goldman’s equally radical Russian-born spouse, Alexander Berkman, also among those being sent away, Goldman shared Berkman’s alien status. About to be exiled by her adopted country, the anarchist stood face to face with the bureaucrat who was deporting her.

“Haven’t I given you a square deal, Miss Goldman?” Hoover asked.

“Oh, I suppose you’ve given me as square a deal as you could,” the activist replied. “We shouldn’t expect from any person something beyond his capacity.”

The United States did not recognize the Soviet state; Burford’s 28-day voyage brought the deportees to Finland, where government officials escorted them to the Soviet border. Many were returning to a country they had left when the Czar still ruled.

Within the year, disheartened by Soviet repression, Goldman and Berkman left Russia to live as political vagabonds, supported by Goldman’s writing. Hoover would never again cross paths with Goldman, who died in Toronto, Canada, in 1940. But the fervent anti-communist bureaucrat would ride the momentum of so-called Red raids that he organized in 1919-22 on behalf of U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, then recast himself as “J. Edgar” and go on to head the agency that became U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation until his death in 1972.

In the early 1900s, the Socialist Party was a growing force in American politics, championing worker’s rights and the eventual abolition of capitalism. Though sometimes talking outright revolution, in its activities the party generally emphasized mainstream reforms like allowing women to vote, establishing a federal education department and a nationwide minimum wage, and doing away with child labor. During those decades, American voters elected about 70 socialists to be mayors and state and municipal legislators. Two Socialists served in Congress (See “Reds Scared Away,” April 2019).

In November 1917, after an internal power struggle, the Soviet Bolshevik faction in Russia triumphed. Led by Vladimir Lenin, the Bolsheviks abolished private ownership of estates, nationalized major industries, and suppressed the multi-party Constituent Assembly. The Bolsheviks withdrew Russia from the Great War, killed Czar Nicholas II and his family, and instituted repressive social controls.

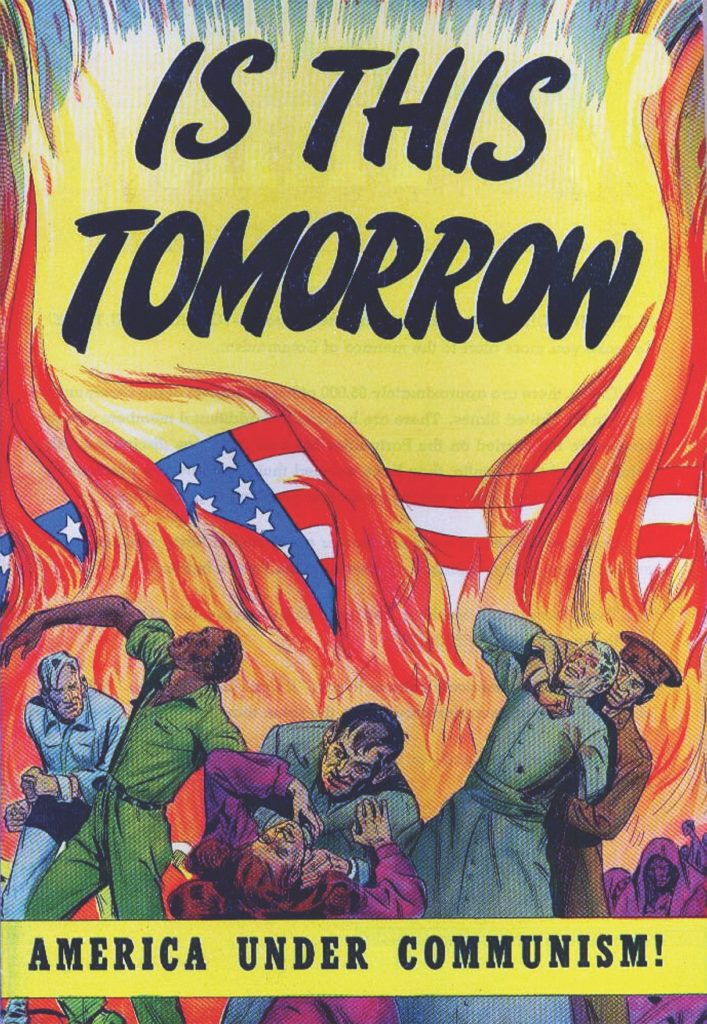

The revolution in Russia divided American socialists into three camps—the Communist Labor Party and the Communist Party of America, both pro-Bolshevik, and a weakened, more moderate Socialist Party. Political anxiety among Americans about Germany, defeated in November 1918, transformed into fear of a communist takeover in the United States—hinted at in a wave of strikes stateside.

In February 1919, more than 65,000 workers, including members of most union locals, staged a five-day general strike in Seattle, Washington. The workers were campaigning for higher wages following two years of wartime wage controls.

That September, the striking Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers shut down steel mills in at least seven states, while in Boston, Massachusetts, unionized police officers walked off the job, resulting in an outbreak of petty crime in that city. Authorities and the press portrayed strikers as Bolsheviks or “Red” fellow travelers, stressing that many strikers were immigrants and quoting them speaking broken English.

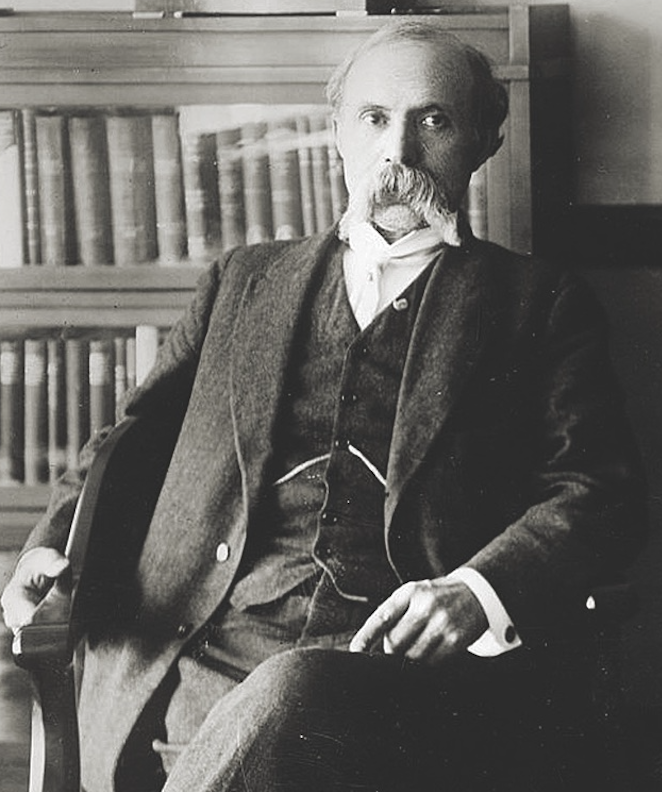

Another group working outside the conventions of the Democratic and Republican parties were anarchists, who since the mid-19th century had embraced individual responsibility, the overthrow of corrupt government, and the role of voluntary associations in maintaining social norms. Some anarchists advocated change through violence, which they called “propaganda of the deed.” One was American anarchist Leon Czolgosz, who had assassinated U.S. President William McKinley on September 6, 1901. Nearly two decades later, on June 2, 1919, adherents of the radical Italian-American anarchist Luigi Galleani set off 11 bombs in eight cities—New York, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Boston and Newton, Massachusetts, Paterson, New Jersey, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC. The blasts’ targets included prominent public officials and a silk company executive as well as Philadelphia’s Church of Our Lady of Victory and the home of a jeweler in that city. An explosive device went off at the Washington, DC, home of U.S. Attorney General Palmer, known as the “Fighting Quaker.”

The anti-personnel bomb meant for Palmer exploded prematurely, sparing the Cabinet member but wrecking his house at 2132 R Street NW. In the wreckage, Carlo Valdinoci, 23, lay dead. On Valdinoci’s mangled corpse was found a leaflet on pink paper reading in part “[T]here will be bloodshed; we will not dodge; there will be murder; we will kill because it is necessary; there will have to be destruction.” Across R Street, Palmer’s neighbor, Assistant Navy Secretary Franklin D. Roosevelt, was returning from a dinner party with wife Eleanor when he heard the blast. After making sure his family was safe, Roosevelt rushed to help.

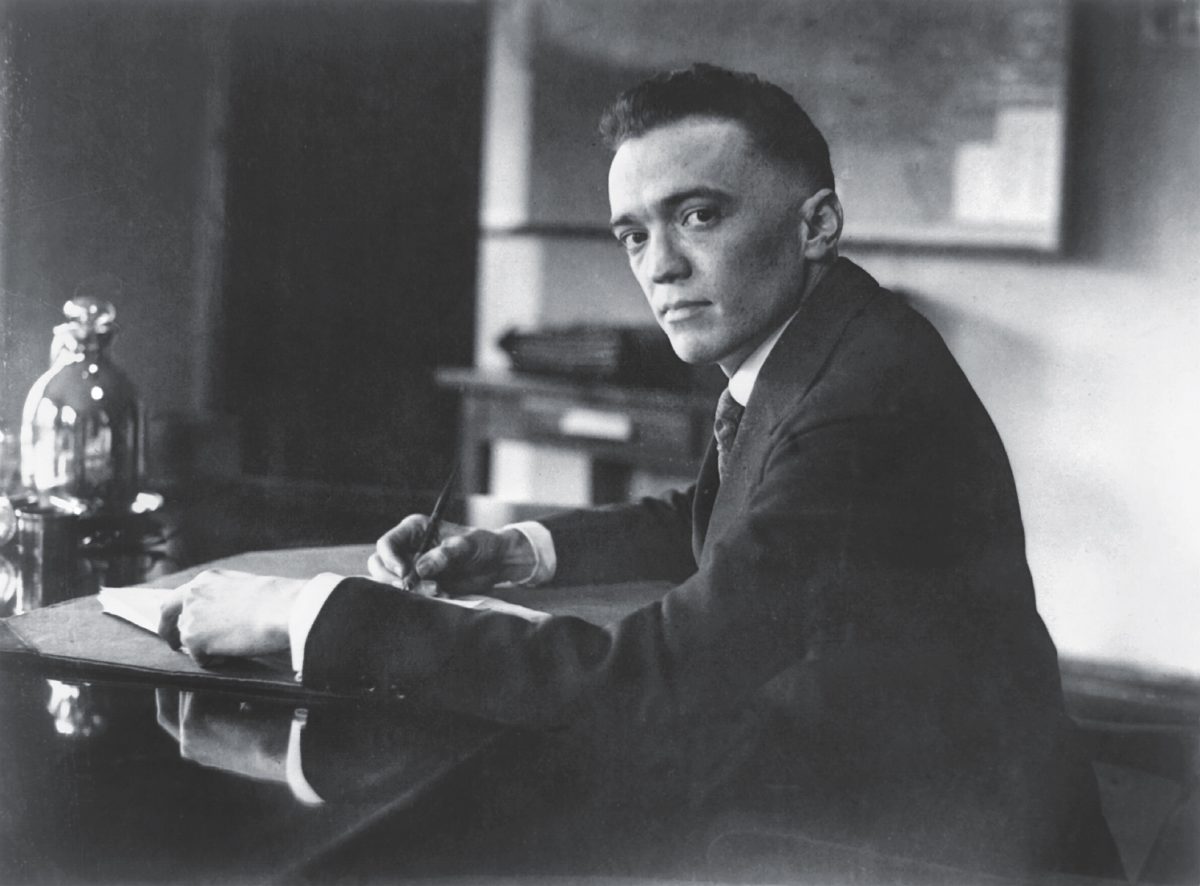

The attacks convinced Palmer, a Democrat with ambitions to run for president, that he had to move against foreign-inspired radicalism. He began coordinating with chiefs of police in major cities, and at Justice established a Radical Division to monitor and neutralize radical groups and individuals. To head the unit, Palmer appointed Washington native Hoover, 24. The government clerk’s son had loved serving in his public high school’s cadet corps. He was an excellent debater, arguing forcefully against female suffrage and abolishing the death penalty, and was valedictorian of Central High’s class of 1913. Obtaining a law degree at George Washington University, also in the capital, young Hoover hired on at the Justice Department in 1917. He worked long hours, meticulously maintained a neat desk, and was a fiend for organization. In two years, superiors promoted him five times, including a wartime stint gathering intelligence on German aliens living in the U.S.

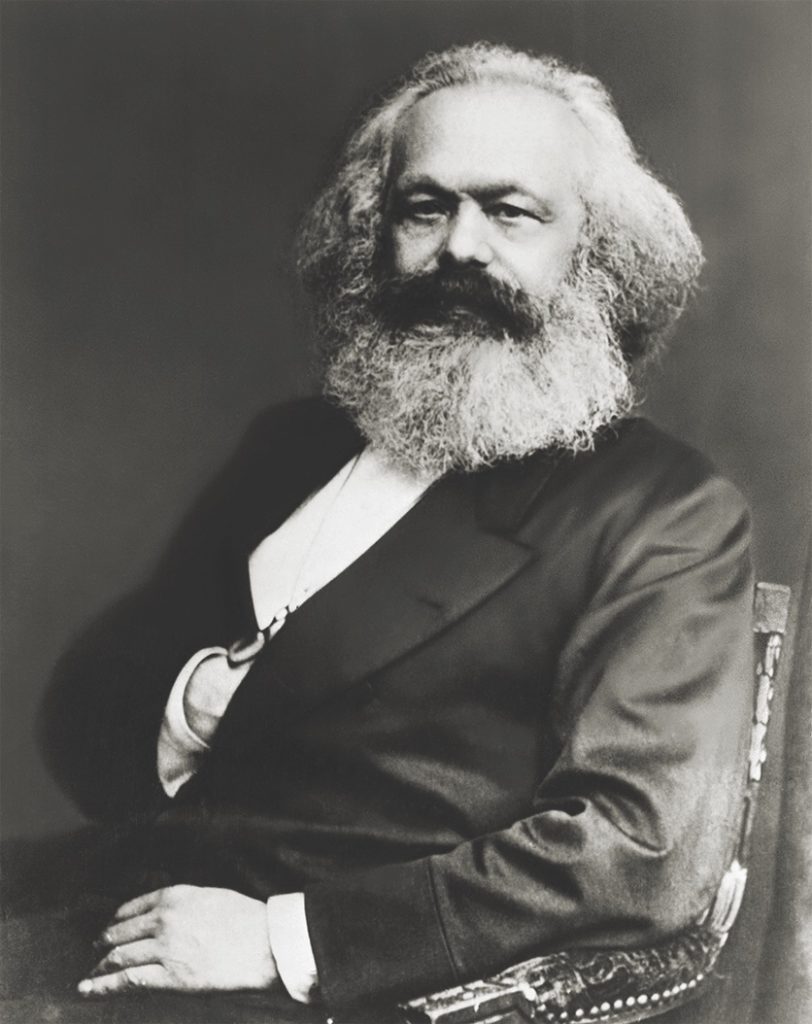

The growth of interest in the writings of Karl Marx and other radicals horrified the young conservative. Hoover soon had organized an archive of 50,000 index cards on radical individuals and groups. Palmer proposed, under the 1918 Immigration Act, to exile as many as possible of those on Hoover’s index cards who were not American citizens. Hoover believed alien radicals had penetrated the American labor movement to a dangerous degree, that left-wing groups had ties to Moscow, and that those groups could help stage an uprising. The 1918 law allowed deportation of aliens who were professed anarchists or who espoused violent overthrow of the United States. Palmer made clear his lack of interest in due process. Hoover endorsed deportation, even though deportation was not a Justice Department responsibility.

Any deportation program required the cooperation of federal immigration officials reporting to the Labor Department. Immigration chief Anthony Caminetti challenged Palmer’s notion on constitutional grounds—until Hoover persuaded Caminetti to go along.

For the first raids, undertaken as a trial run, Hoover focused on the Union of Russian Workers. Since 1907, that émigré organization, which had anarchist ties, had been offering newly arrived immigrants a social setting and giving classes in subjects like English and math. Hoover saw the longer-established URW as a better target than the two domestic Communist parties, which had formed only months before.

On October 30, 1919, Hoover wrote confidentially to immigration director Caminetti,. He advised Caminetti that agents of the Bureau of Investigation, the Radical Division’s parent body, would be sending Hoover “affidavits setting forth the names of the secretaries, delegates and organizers of each local [of the URW]. The department is desirous of obtaining the cooperation of your office in rounding up these undesirable aliens.” Palmer and Caminetti gave the go-ahead. Palmer’s ties to police chiefs smoothed the way, particularly in New York, where in March cops had raided the local URW.

A. Mitchell Palmer

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Karl Marx

Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG/Getty Images; MPI/Getty Images; Bettmann/Getty Images

Palmer and Hoover scheduled raids for November 7, 1919, the second anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. Federal agents supported by local police moved in 18 cities against URW offices and locations members were said to frequent. These included a Russian-language theater in Detroit and a pool hall in Monessen, Pennsylvania, a steel town near Pittsburgh. In raids that often turned violent, arrests nationwide neared 1,100. Most of those arrested proved to have no connection to the Union of Russian Workers—or to be American citizens.

In his 2008 book From the Palmer Raids to the Patriot Act, Christopher M. Finan describes how Russian-born Mitchel Lavrowsky, who had filed papers seeking U.S. citizenship, was teaching algebra at Russian People’s House in Manhattan on November 7, 1919, when armed men identifying themselves as Justice Department agents entered the room. One asked Lavrowsky to remove his glasses. When he did, the agents beat him, threw him down a flight of stairs, and arrested him. Upon realizing their prisoner did not belong to the Union of Russian Workers, Lavrowsky’s captors sent him home with fractures of the skull, shoulder, and foot.

During the early morning raids, Hoover stayed at his desk, conferring with agents by telephone and preparing press releases. A November 8, 1919, Justice Department statement said that raiders had captured a counterfeiting operation in Newark, New Jersey, rooms rented by two URW members. The release added that authorities had found bomb-making materials such as gunpowder, copper and brass wiring, and batteries in a URW member’s Trenton, New Jersey, home. The URW was “more radical than the Bolsheviks,” the statement claimed, adding that “its principles do not favor the Bolshevik form of government, but they are willing to accept the support of any radical or group of men as an expedient for furthering their own particular needs.” The media-savvy Hoover, with Assistant Attorney General Francis Garvin, set up an office to produce releases and pitch them to editors and reporters.

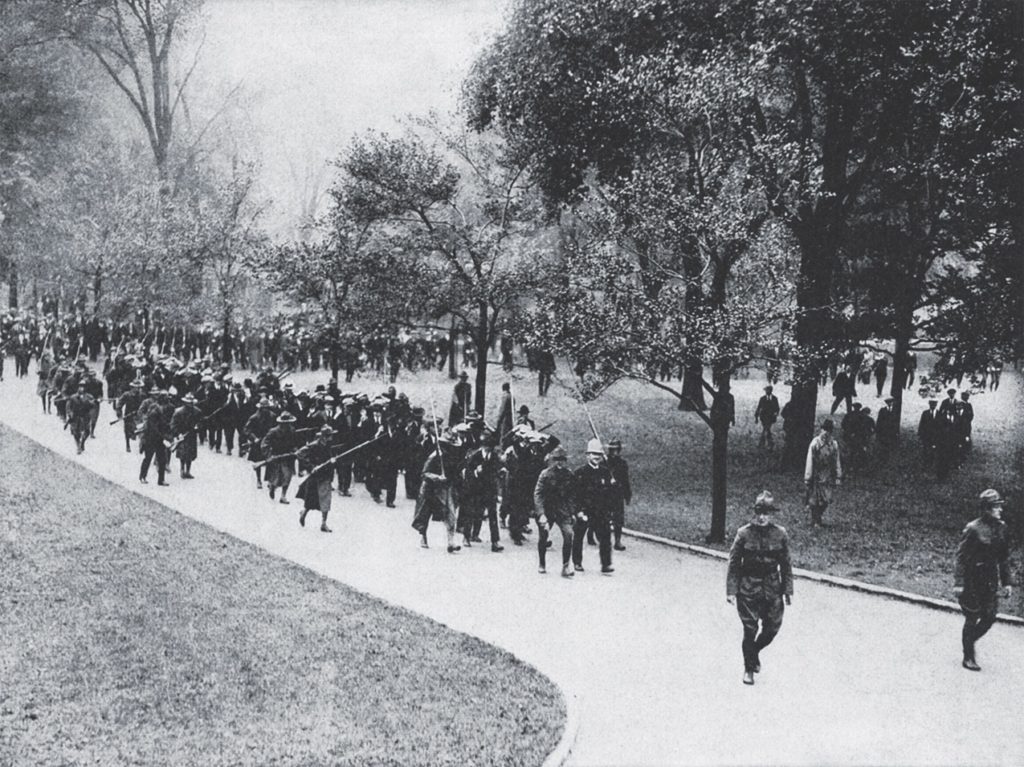

Playing the long game, Hoover let Palmer, about to run for the presidency, take credit for the raids and the expulsion of Goldman, Berkman, and the rest. Looking forward to having a patron in the White House, Hoover began planning raids for January 1920 on Communist Party and Communist Labor Party members and like-minded leftists. Still needing warrants from the Labor Department, Hoover badgered officials there to work faster and hectored their bosses to broaden the warrants’ scope. In an effort to obtain maximum results, Hoover had his agents arrange for informants they had planted in communist groups to schedule meetings on January 2, the night the raids were scheduled. Agents were to break into homes and offices and confiscate any books and papers they found. Overnight that Friday, Justice Department agents made about 2,800 arrests, invading a party in Detroit, Michigan, dances in Lynn and Chelsea, Massachusetts, and an evening class on auto repair in Chicago, Illinois.

As had been the case the previous November, the January raids were brutal. Arresting Russian immigrants in New Hampshire, authorities transported the prisoners to Boston. To move their charges to a federal detention facility on Deer Island in Boston’s harbor, police paraded the shivering prisoners in shackles and chains past taunting onlookers. On Deer Island, the prisoners endured frigid, unsanitary conditions. In Detroit, the Nation reported, authorities warehoused 800 prisoners for a day, unfed, in a federal building equipped with one water fountain and one bathroom. Police then dispersed the 800 among local precincts. At one station house, about 130 prisoners packed a 24’ by 30’ room. Prisoners had to sleep on the floor. Their sole nourishment came from friends and relatives. Release of American citizens and those with no radical ties left Detroit police holding only 300 prisoners, who were shunted to Fort Wayne, an old military bastion on the Detroit River, to await trial. In New York City, more than 500 prisoners were warehoused at Ellis Island.

U.S. Attorney General Palmer, right, at his home in Washington, DC, after an anarchist accidentally blew himself to bits there. (Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock Photo; Library of congress)

When authorities complained that warrants in hand covered only about 150 of those inmates, Hoover pressed Caminetti to speed the warrant mill. The Labor Department had set bail at $1,000 per prisoner—for many, a year’s wages. Hoover urged Caminetti to increase that sum.

Again making his desk a command center, Hoover fielded calls and telegrams, many from officials seeking additional warrants to cover persons not on the original suspect list but arrested nonetheless. Hoover could only pressure Caminetti to get those warrants out. Local officials had trouble finding room for detainees and officers to guard them. Hoover’s media presence began to pay off personally. On January 27, 1920, The New York Times, quoted “J.D. Hoover” as saying about two-thirds of aliens taken into custody were “perfect cases” for deportation because of their membership in the two Communist parties, and that two, three, or more “Soviet Arks” would be made ready, pending convictions.

Raids continued for six weeks or so. In Paterson, New Jersey, on February 14, with Hoover himself on hand, G-men arrested 29 members of Italian anarchist group L’Era Nuova.

At a print shop used by the group, agents found reams of pink paper resembling the stock of the leaflet found in Palmer’s front yard after his house was bombed.

Those January actions netted fewer than 100 deportable alien radicals. One reason was President Woodrow Wilson’s March 1920 appointment of civil libertarian Louis Post as acting secretary of labor. Studying the paperwork, Post found many warrants for immigrant radicals improper, whether because federal agents had broken the law or because the parties named were not true communists but merely had attended a party meeting or enrolled in a class at a social center that also hosted a radical group. By May 1920, Post had dismissed about 75 percent of cases reviewed. He concluded that the Communist Labor Party posed less of a threat than the Communist Party did, so he freed all defendants arrested for belonging to the CLP. Post also reinstated a Labor Department rule, earlier eased at Hoover’s demand, that agents making arrests promptly inform prisoners of their right to counsel. Deportation hearings, according to Post, showed most alleged defendants to have been “working men of good character who have never been arrested before, who are not anarchists or revolutionists, nor politically or otherwise dangerous in any sense.” Palmer enlisted allies in Congress to oust Post, but the acting labor secretary stood fast.

At Palmer’s instigation, Hoover directed agents to investigate Post for links to radical groups. None turned up, but in his lawyering days Post had been on friendly terms with Emma Goldman. He’d defended the radical in free-speech fights and once amicably debated anarchism with her at his home.

Anxiety-Ridden Era

Although the fighting never crossed the Atlantic, save for a few acts of sabotage, the First World War deeply disturbed Americans, heightening fears of an “enemy within.” In July 1916, German operatives triggered a blast on Black Tom Island in New York Harbor, detonating almost two million pounds of munitions meant for the Allies in Europe. In early 1917, discovery of the Zimmermann telegram revealed a plot by Germany to enlist Mexico as an ally against America if the United States sided with the British and French. That April, America declared war on Germany, arousing harsh suspicion of anyone or anything Teutonic. German Americans were pressured to buy war bonds to prove their loyalty, harassed for speaking German, and forced to kiss the flag. Sauerkraut was renamed “liberty cabbage.”

In 1918-19, the misnamed Spanish influenza pandemic, which may have started among military trainees at Fort Riley, Kansas, infected around a quarter of the American population and killed about 650,000 before becoming a global scourge. On domestic front pages, the pandemic and the war shared headline space with the Russian Revolution. That uprising, which remade czarist Russia into a socialist state, in the process slaughtering the Czar and his family, appealed to some Americans and horrified others.

President Woodrow Wilson attacked the new Russia as “government by terror, government by force, not government by vote.” American unions’ increasing power, which the war solidified, met resistance when peace returned. A wave of strikes—steelworkers, miners, even police—in 1919 brought cries that organized labor was a socialist enterprise intent on bringing down the republic. The febrile language used lately against German Americans now was turned on supposed leftists, and soon alarmists were seeing socialist and communist threats everywhere in America. The Red Scare had begun. —Raanan Geberer

On June 1, 1920, referring to what he considered Post’s obstructive behavior, Palmer, with Hoover sitting alongside, told the House Rules Committee, “By [Post’s] self-willed and autocratic substitution of his mistaken personal viewpoint for the obligation of public law, by his habitually tender solicitude for social revolutionists and perverted sympathy for the criminal anarchists of this country, he has consistently deprived the people of their day in court.” Palmer did not mention that Post had signed Goldman’s deportation order.

In a personal scrapbook that he kept, Hoover mounted a poem, “The Bully Bolshevik,” possibly his own work:

The “Reds” at Ellis Island

Are happy as can be

For Comrade Post at Washington

Is setting them all free

They’ll soon be raising hell again

In every city and town

To bring on revolution

And the USA to down

Palmer’s and Hoover’s stances enraged progressive lawyers and their allies. In May 1920, the National Popular Government League published a white paper, whose authors included leading attorney Felix Frankfurter, Harvard Law School Dean Roscoe Pound, and Harvard Law Professor Zechariah Chafee.

The white paper excoriated the Justice Department for letting agents beat prisoners, make arrests and seize property without warrants, use agents provocateurs, and force confessions. Detailed affidavits from raid victims are included in the report—bit.ly/3zhwdsd.

Palmer and Hoover defended the raids and deportation orders. In “The Case Against the Reds” in the February 1920 issue of The Forum, a monthly magazine, Palmer wrote, “My information showed that communism in this country was an organization of thousands of aliens who are direct allies of [Bolshevik leader Leon] Trotzky [sic]. Aliens of the same misshapen caste of mind and indecencies of character.” Hoover told a Labor Department hearing that Communist Labor Party membership justified deportation. The party, Hoover declared, was “a gang of cutthroat aliens who have come to this country to overthrow the Government by force.” He attributed to communist organizations the influence behind recent strikes, The New York Times reported.

Palmer predicted that on May 1, 1920, American reds would start a revolution. When May Day came and went with only scattered demonstrations, Palmer’s sails sagged. The press started to ridicule the Red Scare. On June 23 in Boston, Judge George Anderson ruled membership in the Communist Labor Party or the Communist Party insufficient as grounds for deportation. That ruling was reversed on appeal, but times had changed. Palmer’s presidential campaign collapsed. Even after anarchists bombed Wall Street in September 1920, killing 38 people, few calls arose for Palmer-style raids. Republican Warren G. Harding won the White House.

Declaring his belief in civil liberties and due process, the adaptable Hoover maintained that during the raids he had been following orders, blaming the infamous warrants on local agents. The General Intelligence Division resumed its original name, its scope of work expanding beyond radical politics.

President Harding died in office. Successor Calvin Coolidge in 1924 named prominent New York attorney Harlan Stone U.S. attorney general. Stone appointed Hoover director of the Bureau of Investigation, soon to be renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation, a bastion of crime fighting, intelligence gathering, and press releases. Hoover remained a resolute foe of communism until the day he died.