When his home state was a political borderland, artist’s most famous works celebrated frontier democracy

In 1843 artist George Caleb Bingham, 32, was cross that fame and fortune had not caught up with his ambition. However, that summer the Missourian visited Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, steeping his eye in the work of William Sidney Mount, Emanuel Leutze, John Lewis Krimmel, and other American artists painting scenes of everyday life. Bingham was turning his approach and technique in these role models’ direction when illness reminded him of life’s fragility. Recovered, encouraged, and chastened, he took a fresh creative tack.

Bingham was a roil of contradictions. His affability won him many friends, but he could be vindictive and unforgiving. He saw art that glorified the common man as his ticket to riches. He criticized politicians yet longed to be one. For much of his life, he owned slaves, but backed the Union. His Missouri River and frontier paintings are his lasting legacy, but in his lifetime, works on political themes were his main source of fame. Bingham’s American genre images of a young democracy continue to resonate.

George Caleb Bingham was born in Virginia in 1811. In 1818, after Henry and Mary Bingham lost their farm, mill, and most of their slaves, the family moved to Franklin, Missouri. Henry Bingham became an innkeeper, businessman, and judge. Malaria struck him, and by 1823 Mary was a widow raising George and six siblings operating, with George’s help, a school for girls. The works of an itinerant artist who passed through Franklin—these “limners” traveled with stocks of canvases painted with male and female figures, faces blank, which they completed—piqued the youth’s curiosity about painting, at which he showed talent.

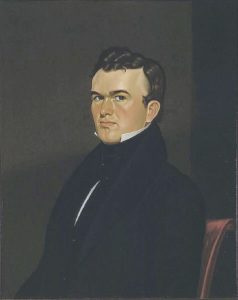

In 1825 a flood on the Missouri River destroyed Franklin. The Binghams moved to a farm in nearby Arrow Rock. George apprenticed with a cabinetmaker, toyed with entering the clergy, and considered studying the law. Instead, he took up palette, easel, and brushes and soon was earning a living painting portraits—“doing heads,” he called it. A decade of doing heads gained him a regional reputation and friendship with attorney, landholder, and politician James Rollins. A year Bingham’s junior, Rollins became a lifelong patron. He introduced Bingham around, coached him at business, and encouraged him to develop his own style. Excluding two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, Rollins spent most of his adult life in Missouri. Bingham traveled far and wide, regularly corresponding with his friend and ally as he completed commissions such as a portrait of Missouri political kingpin Meredith Miles Marmaduke.

Politics underpinned the Rollins-Bingham friendship, reflecting in microcosm the extent to which politics had become a national pastime, supplying Americans with an engaging blend of civic duty, entertainment, and religion. Ennobling yet somehow distasteful, politics fascinated Bingham, a member of the Whig Party. He filled letters to Rollins with criticism of Democratic President Andrew Jackson and his policies, including the Specie Circular, an executive order requiring buyers of government land to pay in coin. The order helped precipitate the Panic of 1837, a nationwide financial crisis that doomed many banks, directly affecting the artist when portrait customers’ checks bounced.

In 1836, Bingham married Elizabeth Hutchinson, who bore him a son. The Binghams built a house in Arrow Rock. A second child died in infancy. Bingham traveled alone to Philadelphia and for the first time visited the Academy of Fine Arts, where he encountered the vogueish genre painting style–simple, plain, American. The approach attracted Bingham, but he worried about its commercial potential. Back in Missouri, still a passionate Whig, he applied his artistic skills in the 1840 election by painting his first piece of political art—a four-panel banner, each segment six feet square, stating the Whig platform, praising local candidates, and extolling Whig presidential candidate William Henry Harrison. Seeking a new market for portraits, Bingham moved his family to Washington, DC. In letters to Rollins he discoursed on Missouri politics, claiming no interest in public affairs and promising to get involved only if another “corrupt dynasty” of Democrats emerged.

Portrait work in the capital ran shallow. In 1841, son Newton died of croup, throwing his father into despair that worsened when President Harrison succumbed to what is now thought to have been typhus. That Elizabeth bore another son, Horace, barely consoled her shattered husband. The family moved to Petersburg, Virginia, but by fall had caromed back to Washington. Elizabeth and Horace returned to Arrow Rock; through 1842-43 George eked out a living in the capital. In summer 1843 he returned to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts; while in Philadelphia he survived his own bout with illness, and, inspired, he narrowed his focus to what he knew—Missouri and politics—and returned to his literal roots.

Admitted to the Union in 1821 under the compromise named for it, Missouri was a hub of riverine commerce through which passed French trappers, Native Americans, settlers, mountain men, and slaves. For an artist, subjects and scenes abounded. Bingham was wondering how to capitalize on what he beheld when he joined the American Art Union, a collective of nearly 10,000 dues-paying members. Members could submit paintings for an annual juried review, from which the Union chose and bought the best canvases, from which lithographs were struck. The body exhibited each year’s champions in New York City and by lottery distributed the originals among members. Besides offering fair prices and valuable exposure, the system mass-produced prints, circulating them to Union members.

Bingham kept at politics. During the 1844 campaign he created banners for presidential candidate Henry Clay and other Whig candidates. In 1845, he submitted four paintings for Art Union review, including a work he titled “French Fur Trader and His Half-Breed Son”—now known as “Fur Traders Descending the Missouri.” All were purchased by the Union and given away by lottery, but none was chosen for reproduction as a mass-marketed print. The following year Bingham submitted another four canvases. Union judges chose “The Jolly Flatboatmen” to be engraved. The Union paid $350 a canvas—today, $10,500. Bingham’s portrait commissions multiplied. The extra income helped; he and Elizabeth had had a another child, Clara.

In 1846, Bingham ran for a seat in the Missouri legislature. He appeared to have won by a narrow margin, but opponent Erasmus Darwin Sappington, a brother-in-law of Governor Marmaduke, at one time a Bingham portrait client, contested the decision. The Democrat-controlled legislature handed Sappington the seat. “An angel could scarcely pass through what I have experienced without being contaminated,” Bingham wrote. “God help poor human nature. As soon as I get through with this affair and its consequences, I intend to strip off my clothes and bury them, scour my body all over with sand and water, put on a clean suit and keep out of the mire of politics forever.” His bleak resolve did not last. By 1848 Bingham had spoken at the state Whig convention and in the subsequent election unseated Sappington in the legislature.

In November 1848, Elizabeth, soon after delivering another son, died of tuberculosis. Grieving, Bingham left Horace, Clara, and baby Joseph with his mother and began to his legislative term. Baby Joseph died. An inconsolable Bingham focused on his job until session’s end, when he moved to New York City to paint. Cholera killed his brother Henry’s wife and three children. His sister Amanda and her family needed a place to stay; Bingham installed them at the farm in Arrow Rock. Through Rollins, Bingham met and married Eliza Thomas, 20, whose companionship lifted his spirit, beginning a personal and artistic resurgence.

Between the late 1840s and the mid-1850s, a renewed Bingham produced a series of remarkable paintings on political themes—not highfalutin’ canvases but images of a process rife with wheeling and dealing and shenanigans, a panoply of polls staying open for days on end, campaigning taking place all the way to the ballot box, ballots being anything but secret, and citizens openly selling votes. Despite or because of his treatment of these systemic flaws, Americans, convinced their democracy had no peer, loved the rumpus the works showed. Participants had developed the “the habit of trained and disciplined good temper toward the opposite party when it fairly wins its innings,” philosopher William James wrote.

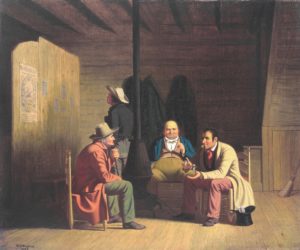

Bingham understood all this, as well as the need to portray the democratic jangle in all its clangorous glory. In 1849, he finished “Country Politician,” presenting an eager candidate addressing two half-hearted listeners as a third man warms himself and reads a circus poster. The Daily Missouri Republican claimed the image portrayed a discussion of the Wilmot Proviso, a bid to ban slavery in territories gained from Mexico. That analysis is understandable. Local and national politics were often the same. In 1852, Bingham debuted the 251/8˝x303/16˝ “Canvassing for a Vote,” a variation on the “Country Politician” theme. This outdoor scene adds a character but includes another inattentive individual—a recurring Bingham trope.

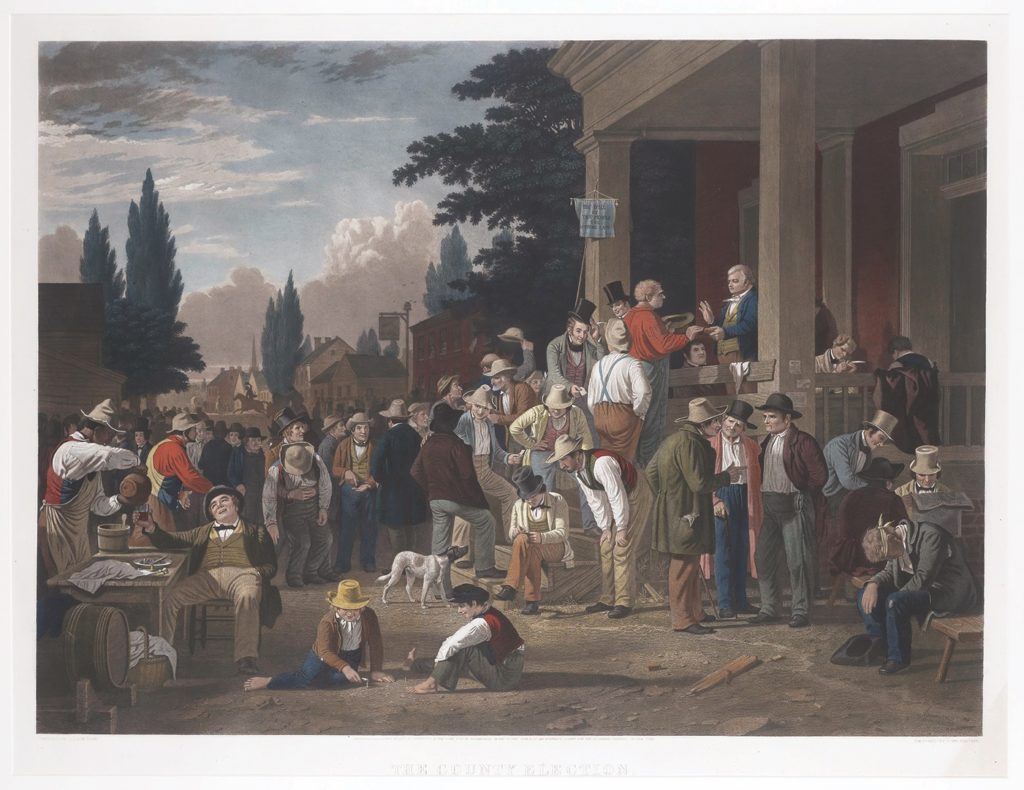

In 1852, angry at learning that the American Art Union had been shortchanging him, paying other artists as much as $1,000 per canvas when he was getting only $350, Bingham quit the collective. Before he could follow through on a threat to sue, New York authorities declared the Union’s lottery system illegal and shut down the operation. Rebounding from his ire, Bingham produced “The County Election”—at 38”x52”, much larger and more detailed than earlier works as well as emphatically admiring of democracy. “All who have ever seen a county election in Missouri are struck with the powerful accumulation of incidents in so small a space, each one of which seems to be a perfect duplication from one of the momentous occasions of real life,” a reporter wrote. Bingham’s individuals each seem important, but certain among them hold the eye: a judge taking an oath, a passerby being offered what may be a ticket. Bingham himself may be that man taking notes. The child playing mumblety-peg comes from a sketch of the author’s son, Horace. The speaker making his point, men debating, a newspaper reader, a drink buying a vote, a drunk voter being dragged to the ballot box, a sign reading “The Will of the People is the Supreme Law”—all make individual points. Critics mostly praised “Election,” and engravings of the work sold well, though some critics derided the work as slanderous and maleficent. “Mortifying…worthless,” wrote a reader to the editor of a paper in Lexington, Kentucky. The crowded canvas of “Election” became a Bingham signature.

In 1852, Bingham attended Missouri’s Whig convention, at which party members elected him a delegate to the national convention. That cycle the Whigs foundered amid the sectionalism dividing the nation; Democrat Franklin Pierce took the White House, prompting Bingham to gripe to Rollins but then add, “I forgot that I am a painter and not a politician.” The Whigs expired. Bingham, despite owning slaves, became a Republican.

Bingham continued painting everyday scenes but needed more money than single works were bringing. Recalling the Art Union’s lithography operation, he began recruiting and supervising engravers and promoting subscriptions to his work, as well as flogging his output at lectures he gave. In 1853 letters to Rollins the artist describes a dervish-like schedule of collaborating with Philadelphia engraver John Sartain to churn out 12 to 15 copies of “Election” per day, ordering better paper from Europe, and working on his next painting, a routine he maintained for years.

During 1854 Bingham finished the 42½”x58” “Stump Speaking,” corralling familiar characters into a crowd listening to candidates. “The gathering of the sovereign is much larger than I had counted upon,” he told a friend. “A new head is continually popping up and demanding a place in the crowd, as I am a thorough democrat, it gives me pleasure to accommodate them all.” Some people in the image listen intently, others ignore the chattering on the dais. Some debate among themselves. Bingham included what he called a “wiry politician grown gray in the pursuit of office,” and “behind him a shrewd, clear headed opponent, who is busy taking notes, and who will, when his turn comes, make sophisms fly like cobwebs before the housekeeper’s broom.” The fat man onstage is long-time Bingham foe and portrait subject Meredith Miles Marmaduke. The hoi polloi loved “Stump Speaking,” which Bingham considered his best effort for its stab at reality. “Instead of the select company my plan first embraced, I have an audience that would be no discredit to the most populous precinct of Buncombe,” the artist wrote, referring to the North Carolina county whose name birthed the term “bunkum” and later “bunk,” connoting meaningless political claptrap.

In 1854, Bingham undertook a yearlong project. “The Verdict of the People,” 46”x65” (facing page), ranks as his largest, most complex work. Bingham depicts the election-day excitement of votes being tallied and results announced. He dots the canvas with exaggerated facial features, inventive use of light and shadows, figures’ stances, the flag, campaign signs, and a stack of hats on a character’s head. For the first time in a Bingham painting, African Americans are present in a notable way. He depicts more women—“Freedom for Virtue,” a banner at the upper right reads, “Remember the Ladies.” Onlookers, faces showing joy and doubt, read the results: 1,406 to 1,410, a near-run thing. Was Bingham referencing his own contested loss of years before? Some critics claimed he was mocking former foes. The rough and tumble, as in other Bingham works, suggests that despite its imperfections America is a place in which to take pride. “Verdict” concluded his series.

By the mid-1850s, Bingham was writing to Rollins of the nation’s problems and his own sense of disengagement. In 1856, he told his friend that thanks to Democrat James Buchanan’s election he had forsworn his “fond elusive dream” of a diplomatic appointment and instead would “bide my time and live for the next four years upon the fruits of the pallet [sic] alone.” It is unclear whether Bingham sold or freed his slaves, but a remark to Rollins—“I myself have gone clear over to the black Republicans.”—suggests the latter. A trip to Europe led the Binghams to settle in Dusseldorf, where George studied and worked on historical portraits for the Missouri Legislature until the family returned home in 1859. Eliza delivered son James Rollins Bingham in 1861.

With civil war declared, Bingham joined the U.S. Volunteer Reserve Corps as a private. He was soon appointed company captain in the Home Guard protecting Kansas City. In 1862 he accepted an appointment as Missouri state treasurer, serving through the duration to emerge a Democrat as a result of his disaffection with Radical Republicans. In 1866, Bingham lost a primary for a congressional seat, and in 1868 he served as an elector at the Democrats’ state convention. That year he exhibited his most controversial canvas. In topic and title, “Order No. 11” invoked an 1863 raid on Lawrence, Kansas, in which pro-Southern guerrillas destroyed that town and killed more than 150 male residents. In response, Union General Thomas Ewing, at the insistence of Lawrence resident and U. S. Senator James H. Lane, issued General Order No. 11. The order required that in western Missouri, where support for the rebel guerrillas was highest, all residents regardless of allegiance had to vacate the region. Some moved into nearby towns. Others left entirely. Bingham thought the order an “act of imbecility”—arbitrary, cruel, and likely to cause more violence. “If you execute this order, I shall make you infamous with my pen and brush so far as I am able,” he told Ewing, who ignored him. The 54”x66” canvas depicts a pro-Confederate family being evicted as Union troops burn fodder, destroy furniture, and loot the premises. A young man has been shot. Women are weeping.

Ever industrious, Bingham sought portrait commissions, exhibited work, and hawked engravings. In 1874, the Kansas City Board of Police Commissioners named him president. In 1875 Governor Charles Hardin named him Missouri adjutant general, a role in which Bingham worked tirelessly to recover money for war claims until 1876, when illness forced his resignation. That year Eliza, who had grown delusional, was institutionalized and soon died. Bingham rallied, and in 1877 was appointed professor of art at the University of Missouri. He married widow Martha Livingston Lykins, and for a year they traveled, and he worked.

In February 1879 Bingham’s health declined; on July 7, he died of gastroenteritis.

James Rollins spoke at the funeral. In eulogies, Bingham’s life in politics outranked his artistry, a pattern that seemed destined to hold until Martha Bingham refocused attention on his oeuvre. The widow’s diligence, along with several important exhibits during the 1930s, cemented appreciation for his work’s evocation of Americana, assuring George Caleb Bingham his place in the pantheon.

_____

Where the Binghams Are

Many Binghams have been lost, but most of his classic works are accessible. His greatest Missouri River paintings, “Fur Traders Descending the Missouri” and “The Jolly Flatboatmen,” hang at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. respectively. “Country Politician” is displayed at the de Young Museum in San Francisco and “Canvassing for a Vote” is at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. “The County Election,” “Stump Speaking,” “The Verdict of the People,” and “Self Portrait” are owned by the St. Louis Museum of Art in St. Louis, Missouri. “Order No. 11” is at the Center for Missouri Studies in Columbia. —Michael McCray

This story appeared in the June 2020 issue of American History.