Two weeks into the Civil War, students of the Atlanta Female Institute put on a program that included a faux bombardment of Fort Sumter. The Atlanta Daily Intelligencer covered the event. “It became necessary for one of the smallest of the girls to hoist the United States flag, and to keep it standing until the close of the bombardment,” the paper reported. William P. Howard, a teacher at the Institute who directed the event, apparently had trouble finding a volunteer. One girl of about 10 told him, “No, it is not our flag, and I will never hold it.” Two other young ladies also refused. Finally, a reluctant flag bearer was found. She held the Stars and Stripes, though crying as she did so, saying that she hoped she was not disgracing herself.

This was the face of Confederate patriotism, as reported in Atlanta’s leading daily newspaper.

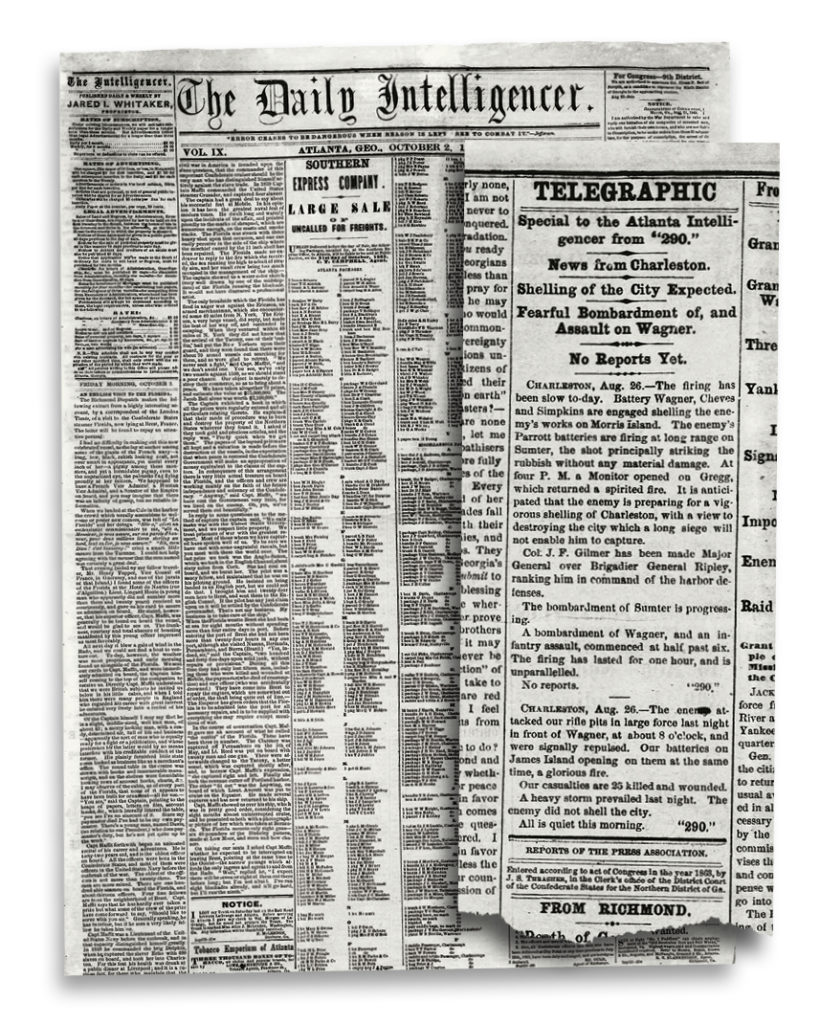

The Intelligencer had been founded as a weekly in 1849, converting to a daily five years later. It was rivaled only by The Atlanta Southern Confederacy, another daily. The competitors strove to scoop one another on big stories, such as the Great Locomotive Chase (Andrews’ Raid) of April 12, 1862. Both papers rushed to print on how Anthony Murphy, William Fuller, and others had captured the Yankee train-thieves. Confederacy staff interviewed the two pursuit leaders; the Intelligencer in turn printed those individuals’ written statements. Both pieces appeared on the 15th. Because the Intelligencer got its morning issues out early, it might have scored the scoop. But the long Andrews article was not on the front page, as one would expect today. Readers looked inside the Intelligencer’s four-page layout; like most papers of the day, it put big stories on page 2, sometimes page 3 (the one that carried its “Telegraphic” column). The first page was mostly ads, anyway.

The Intelligencer was one of 844 newspapers, as counted by the Census Bureau, in what would become the Confederate States of America. Georgia had 105 of them—behind only Virginia—but that number counted dailies, weeklies, and the like. Moreover, in 1860 the U.S. Census posted 3,000 subscribers to the Daily and Weekly Intelligencer, thus ranking it among the top three papers in the state.

Then, as now, a wartime paper’s chief function was reporting the news—and readers expected lots of it. John H. Steele, the Intelligencer’s editor for most of the war, got his information from several sources. Telegraphic dispatches were paramount, especially when received from the War Department in Richmond. To be sure, these were usually very brief—papers paid for wire reports by the word.

Some dispatches proved downright wrong. In its issue of April 8, 1862, this headline blared: “Complete Victory! Great Battle at Shiloh!” The paper had relied on the message General P.G.T. Beauregard sent from the battlefield the night of April 6, after Confederates had pushed Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Federal army back to the Tennessee River. “Thanks Be to the Almighty” screamed the paper’s editorial on the 8th. Even amid later reports that Beauregard’s army had retreated to Corinth, Miss., the Intelligencer continued to crow about 8,000 Union prisoners taken, 70 cannons captured, and so forth.

And the reverse: When bad news came, it was the editor’s job to soften and spin it. Take the Intelligencer’s handling of General Joseph E. Johnston’s retreats through northern Georgia in 1864. After word came that Johnston had abandoned Dalton, Steele assured his readers: “General Johnston, with his great and invincible satellites, are working out the problem of battle and victory on the great chess board at the front.”

The Intelligencer is notable as well for its staying power. By 1865, there were only 253 newspapers still functioning in the Confederacy—and of them, just 20 were dailies. They had succumbed to loss of manpower when printers ran off to join the Army; the blockade that cut off sources of raw materials; rising costs in an inflationary economy; and—to be sure—enemy occupation of key cities such as Memphis and New Orleans.

Then there were the strikes by printers, demanding higher wages. In the spring of 1864, after their workers walked out, Atlanta editors visited the city’s conscript office and addressed the printers’ status. They were exempt from the draft while working, the editors claimed; but now, as they were on strike, the draft officer was encouraged to draft them for Army service. The conscriptor liked the idea. “Gentlemen,” he said, “you are undoubtedly right. I will go to work at once, and as you are here, I will conscript you to begin with.

“Conscript us!” exclaimed the editors.

“Certainly. As you have no printers, you can’t get out your papers. So you no longer belong to the exempted class.”

The editors raced back to their respective offices and contacted the printers’ union. In 15 minutes, everyone was back to work.

During the war, the Intelligencer raised its subscription prices eight times, from $6 a year to $10 per month. Nevertheless, the paper survived the war, although in July 1864, it was forced to flee to Macon, Ga., as Maj. Gen. William Sherman’s forces approached Atlanta. The paper returned in early December to issue a single-sheet “extra” reporting all the damage to the city that the Yankees had wrought. “Whitehall street from Roark’s corner up to Peachtree street is one mass of ruins,” the paper declared after returning to the city; its very offices were among the ruined buildings.

The Intelligencer sometimes sent field correspondents to the battlefront—“specials” who sent back wires and letters relating what they had seen and heard. After General Braxton Bragg expelled reporters from the Army of Tennessee just before the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, Steele was without eyes and ears for the big battle fought in northern Georgia. The editor strained for anything and resorted to printing mere rumors brought down by train passengers. In the newspaper business, this is bad—as Steele found out after the Intelligencer reported, “Gen. [John Bell] Hood’s leg was amputated some distance above the knee, and it is our painful duty to state that he died after the operation.”

Faced with wartime shortages and high prices for newsprint and ink, Southern papers learned to improvise. One solution was to form a press association to have news telegraphed, as the Associated Press in New York was no longer a viable option. The Intelligencer carried the P.A. columns, one of which got the story straight on September 22: “Gen. Hood is not dead.” That wasn’t the last time Steele had to do an about-face.

Then there was the time that the Intelligencer took on President Jefferson Davis. When Steele was away in September 1864, associate editor Dr. I.E. Nagle penned an editorial criticizing the president for apparent neglect of Georgia’s safety. In a speech delivered in Macon on September 23—while he was heading to meet with General Hood south of Atlanta—Davis called an unnamed newspaperman “a scoundrel.” Southerners at the time and historians since have wondered to whom the president was referring. It was Nagle. After returning to his sanctum—the editor’s favorite word for his office—Steele tried to quell the hubbub by admitting it had been his associate. That the president was so alarmed by the paper’s accusations was no small deal. Whether Davis was mollified by Steele’s confession is uncertain.

In its loud, repeated predictions of Confederate victory, the Intelligencer did not go quite so far as the unidentified Johnny Reb who famously asserted, “I have no more idea that the Yankees will whip us than that a chicken can teach Latin”—but it sailed down that same course. At one point, the paper grew so enthused at the prospect of Southern triumph that it actually began envisioning the sorts of territorial demands the Confederate government should exact upon a defeated North.

Similarly, the Intelligencer wasn’t as vindictive as a Columbia, S.C., paper inveighing against Yankees. Upon hearing that a brush fire after the June 1864 Battle of Kennesaw Mountain was burning wounded Federals, it headlined “Confederate Victory Near Marietta! The Yankees Roasting!” Still, in mid-August 1864, the Atlanta paper had some gruesome fun, upon news that 300 prisoners had died at Andersonville in one day, when it did some math: a 6,000-foot-long wagon train to carry the corpses to the graveyard, a trench 600 feet long to bury them; 120 men to dig the grave. “We thank Heaven for such blessings!” the paper exulted.

And while the Memphis Daily Appeal, for example, was unseemly in calling the enemy “azure-stomached miscegenators,” the Intelligenceradopted the terms “ceruleans,” “cerulean abdomens,” and “bluebellies” for Federals—the latter term apparently originated in the war, but its first printed use is uncertain. In May 1864, the paper mocked the enemy as “the Yankees, the terrible, great big, bugaboo Yankees; the fellows with cerulean abdomens or azure corporations.”

It could get even more rancorous. At one point, the Intelligencer claimed those bluebellies had been “gathered from all the purlieus of effete Europe and the North” and were in effect second-rate soldiers: “Dutch immigrants, cheated Irishmen, bamboozled mongrels, miserable contrabands, miscegenating adults and brigades of silly youths with cerulean abdomens, and a sufficiency of Yankees to leaven the whole mess with their accursed principles of injustice and wrong.”

As we will show here, the wartime reporting in the pages of the Atlanta Daily Intelligencer provides an insight into this country’s most devastating conflict, the Civil War.

From the Vault

Exploring the Atlanta Daily Intelligencer’s wartime reporting provides a telling look at the nation’s most devastating period. Below are a few capsules of diverse topics the Intelligencer shared with its devoted readers between 1861 and 1865.

Incredible Clemency

Chivalry was not yet dead in the spring of 1862, as Northern and Southern armies entered their second year of war.

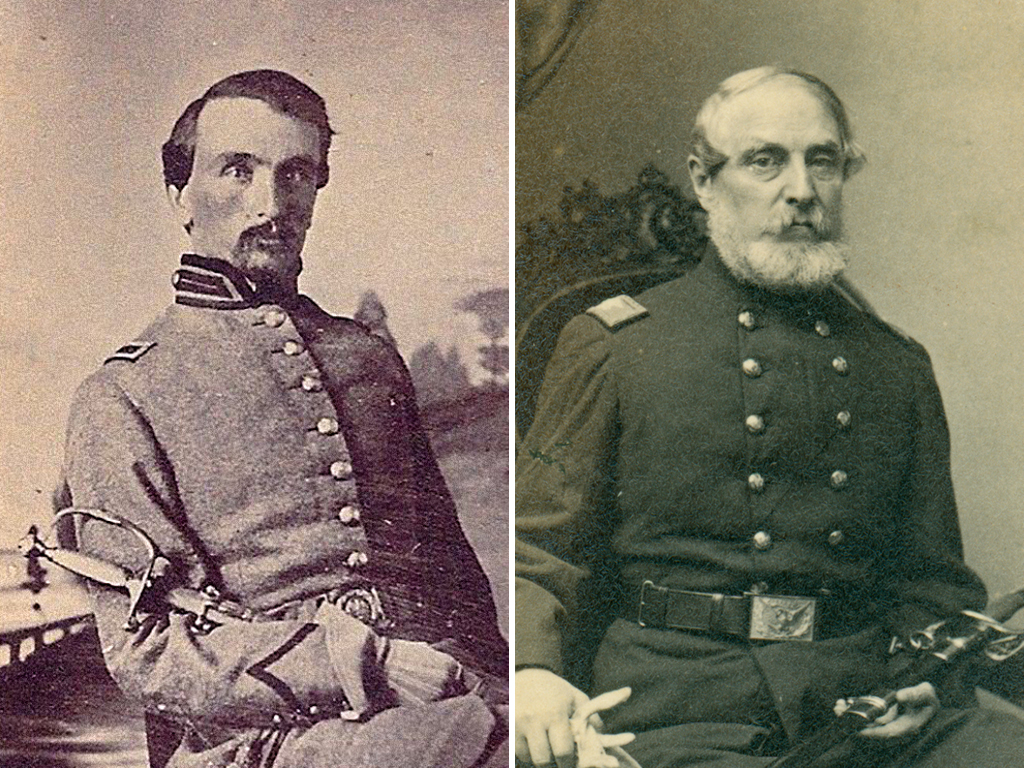

A series of letters printed in the Intelligencer indicates that civility could still exist between gentleman officers of the opposing armies, even as their soldiers sought to kill each other on the battlefield.

During the Battle of Seven Pines, the 35th Georgia was engaged against the 20th Massachusetts a mile north of Fair Oaks Station. After nightfall, a severely wounded officer of the 35th, Lt. Col. Gustavus A. Bull, was brought into the Union lines as a prisoner. The 20th’s colonel, W. Raymond Lee, saw that Bull received medical care. After the next morning’s combat, Lee learned that the 27-year-old Bull had died at 8 a.m. The day after that, June 2, Lee searched for the Confederate officer’s grave, intending to place a headboard upon it. He knew its general location, around a house behind the Federal lines that had been turned into a field hospital, but there were so many graves that Lee could not find the burial site of the slain Georgian.

Two weeks later, the colonel wrote to General Robert E. Lee, whom he had known at West Point (both graduated in its Class of 1829). He revealed Bull’s fate and suggested that someone in Confederate Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s command—against whom his men had fought—might know of the house and its graveyard. General Lee in turn had his staff officer, Major Charles Marshall, mail Colonel Lee’s letter to Bull’s father, a prominent attorney and Superior Court judge in LaGrange, Ga., offering the grieving father assistance in trying to find his son’s grave near Fair Oaks. Mr. Bull asked the editor of the LaGrange Reporter, Charles H.C. Willingham, to print the letters. The Reporter obliged, and the Intelligencer followed suit, publishing the entire correspondence in its July 27, 1862, edition.

Bull’s father never took advantage of Marshall’s offer of assistance to look for his son’s grave in Virginia. Apparently Bull’s remains were disinterred shortly after the war, removed with those of the unknown Union dead, and reinterred in Seven Pines National Cemetery. Today a memorial in the family plot in LaGrange’s Hillview Cemetery reads: “Sacred to the memory of Gustavus Adolphus Bull, whose remains lie among the unknown dead of the battle field of Seven Pines.”

The Death of a Deserter

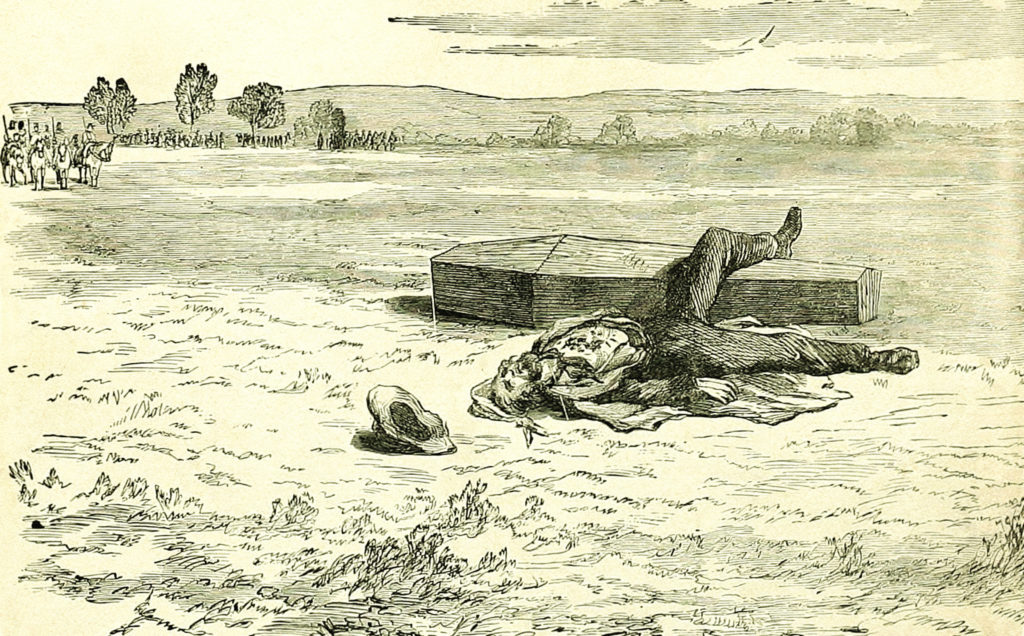

A number of poignant stories found their way into the Intelligencer, such as one about the execution of Private Jacob Adams, a 46th Georgia Infantry deserter. As originally reported by the Charleston Courier and republished by editor John Steele on May 18, 1863, Adams had been executed at the race course outside Charleston, S.C. Confederate troops and the city garrison were formed under arms to witness what would be a solemn and imposing event. They were joined by a crowd of citizens.

Adams was marched into a hollow square at the race course, as a band played a dead march. The funeral strain played by the convicted private’s escort ceased when he entered the square, only to be taken up by the bands of several other commands present.

Reportedly, Adams bore himself with dignity. Standing before a firing squad, he received last rites from the Rev. Leon Fillion. He then knelt upon his coffin, crossed his arms, and, suddenly looking up, took off his hat and threw it to his right. Refusing to have his eyes bandaged, he looked directly at the execution party and awaited the order to fire with perfect calmness.

The order was given—there was a flash, a report, and Adams lay prostrate upon the ground. A surgeon quickly examined the body and confirmed that Adams was indeed dead.

“The execution was an awful but necessary infliction of military justice,” concluded the Courier, its writer adding that the soldiers who had been brought out to witness the execution, particularly anyone secretly pondering likewise slipping out of the ranks, “will be returned to their regiments wiser men.”

Articles about the Charleston execution would be printed as far away as London, Liverpool, and Glasgow—along with information about Adams’ disreputable service record. An Englishman, he reportedly had deserted from the British army and, when caught, was branded with a “D.” After immigrating to America, he had enlisted for a year’s service in the 1st South Carolina Infantry. Adams was arrested, according to the Confederate assistant adjutant general in Charleston, “for attempting to murder a comrade and for other breaches of discipline.” Sentenced to death, Adams would be spared by President Jefferson Davis, who commuted his penalty to imprisonment with ball and chain for the rest of his term of service.

Undoubtedly, Adams was a rough fellow. During his imprisonment, “he several times attempted to murder people though heavily ironed,” the A.A.G. stated. He was also a bounty jumper—one who enlisted, collected a bounty, and then deserted. After his release on September 6, 1862, he joined the 46th Georgia, stationed at Charleston. In October, however, he again deserted but was quickly caught, tried, and sentenced to execution. This time, the punishment was carried out, though not before Adams spent seven months in a Charleston jail.

Adams was one of 103,400 known Confederate deserters. Through the efforts of generals such as Robert E. Lee, most of those caught absent without leave would be given lenient sentences. Indeed, only 229 Confederate deserters were executed between December 1861 and the end of the war. Like Jacob Adams, 204 were by firing squad, 25 by hanging.

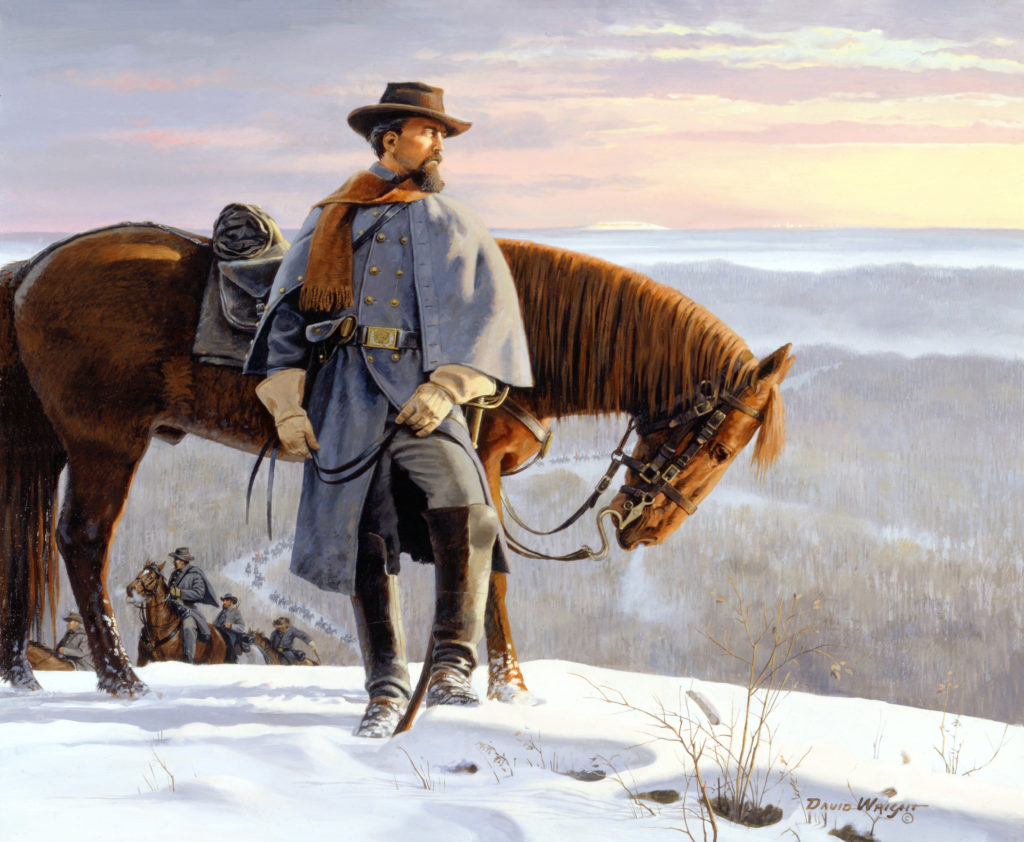

One ‘Fine Steed’

On September 21, 1863—the day after the Confederate victory at Chickamauga, Ga., Nathan Bedford Forrest and his cavalry were chasing William Rosecrans’ beaten army back to Chattanooga. During the running fight, Forrest’s horse was shot in the neck. The general quickly plugged his finger into the wound and kept charging. When he removed his finger while dismounting at the end of the chase, the horse promptly fell dead.

The story is well known. The horse’s name, Highlander, less so.

Less-known still is how General Forrest acquired Highlander in the first place. One could, of course, read about it in The Atlanta Daily Intelligencer.

Earlier that year, on May 3, Forrest and his command gained acclaim by running down Union Colonel Abel Streight and his raiders, forcing them to surrender 25 miles west of Rome, Ga. The Intelligencer joined the Southern press in bestowing its accolades. Rome, after all, was only 55 miles northwest of Atlanta, a likely Yankee target. It was a “brilliant exploit,” the Intelligencer related to its readers on May 6—“a brilliant and dashing affair.” Forrest had bagged a bunch of “Yankee scoundrels,” asserted editor John Steele. “These marauding rascals, these devils in human shape” had ridden toward Georgia “to devastate the country, to capture and destroy Rome, Atlanta, and such bridges on the State Road, as would interfere with transportation, if not effectually to prevent it.”

Atlantans joined the citizenry of Rome in thanking Forrest. On May 10, Steele announced that a fundraising effort had begun to purchase a “fine steed” for the general. In an article titled “A Horse for Gen. Forrest,” Steele informed his readers they could come by the newspaper’s office to contribute. Two months later, Steele exuberantly announced that $2,000 had been raised for that horse and another $1,200 for an elaborate saddle, bridle, and halter. The gift was presented to Forrest in mid-July, with the editor expressing his hope that the general would soon be riding this “splendid charger”—named “Highlander.”

Steele would get his wish.

Sad Telegram

Twelve days after he was shot in the left arm on the second day of fighting at Gettysburg, Lieutenant William Hoyle Nesbit wrote or dictated a telegram to his father in far-away Georgia.

RICHMOND, July 14—To Mr. J.W. Neisbit, care of the Intelligencer:

Dear Father—I am at Jordan Springs Hospital, near Winchester. I lost my left arm at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Come to me. Answer by telegraph. W.H. NEISBET.

The caregiver who handled the young soldier’s missive apparently didn’t know the correct spelling of his name and only that he lived somewhere near Atlanta, so he sent the telegram to the city’s leading newspaper, the Daily Intelligencer.

Editor John Steele published the plea July 26, prefaced by a notice to readers: “The following telegraph dispatch has been received at this office. We do not know the residence of Mr. J.W. Neisbet, to whom it is directed, under our care, and therefore publish it, hoping some one will convey to him the information it imparts.—ED. INT.”

Apparently no one did, but the case of the wounded lieutenant, who turned 22 just 10 days after his Gettysburg wound, worked out well. On August 3, he was granted a 60-day furlough to return home. He resigned from the Confederate Army in November 1863. After the war, he started farming, married, and raised a family north of Atlanta. He died at the age of 83 in 1925, one of approximately 60,000 Civil War amputees.

‘Loathsome Despoilers’

An important feature of the Confederate press was its propagandistic capacity to vilify the enemy, conjuring up especially odious images of Northern soldiers as destroyers of civilians’ homesteads and loathsome despoilers of fair Southern womanhood.

Such is the imagery of a letter first published in the Columbus (Ga.) Times, and reprinted in the Intelligencer on October 25, 1864. The writer, a Confederate soldier in Hood’s army at Jonesboro, Ga., began, “If every man in the Confederacy could look back upon the desolation and ruin that mark the pathway of the Yankee army as they advance, we could then have a spirit of true harmony”—meaning, unity of resolve in the war-torn Confederate States—“and the foul breath that lisps that awful word, ‘reconstruction’”—meaning, reunion with the United States—“would be hushed.” The soldier referred to “desolated homes and fields” left behind by Northern armies marching through the South, and “the desecrated altars from which thousands of women and children have been ruthlessly driven out upon the world, penniless—homeless.”

Then there was “one more spectacle which the fiendish hearts of our invaders have wrought,” the blood-chilling scene that the writer stated was just six miles from where he sat. There an elderly mother and father sat drooped with grief in their little cottage, “once the scene of happiness—now misery.” Sitting beside the parents, as described by the Columbus Times’ contributor, was “a young girl, aged about seventeen years.” She had been raped by Union soldiers, “the victim of the hellish appetite of these more than devils.” The writer had apparently heard the parents’ story about the Yankees: “three of them, in broad day light, before the face of these aged parents, outraged her.” (Rape was a word seldom used in Victorian America.) The soldier-correspondent concluded that one had only to see “the maniac gaze” of the troubled rape victim, to dismiss any thought of “reconstruction or union with such people.”

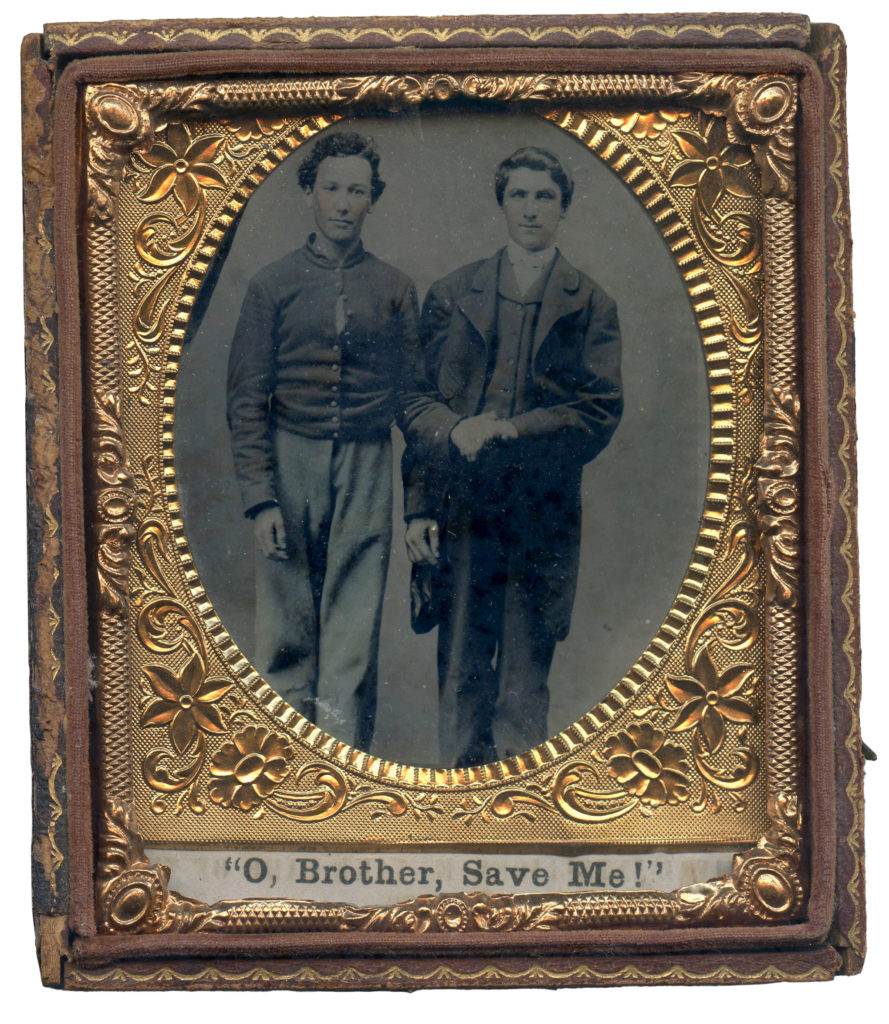

‘War and Its Horrors’

Northern and Southern newspapers occasionally broke free from the martial euphemism and Victorian patina that characterized correspondents’ reporting to give readers brutal glimpses of bloody battlefields. The following account by a soldier in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, written to his father in Charleston, appeared in the Intelligencer’s August 2, 1862, edition:

The painful details of our wounded I will spare you, but will pass to the enemy’s side of the field, where one-half of the number laid; there were men with their arms, legs, and hands shot off, bodies torn up, features distorted and blackened. All this I could see with indifference, but I could not but pity the wounded; there one poor devil, with his back broken, was trying to pull himself along by his hands dragging his legs after him, to get out of the corn rows, which the last night’s rain had filled with water; here, another, with both legs shot off, was trying to steady the mangled trunk against a gun stuck in the ground; there, a fair haired Yankee boy of sixteen was trying with both legs broken, half of his body submerged in water, with his teeth clinched, his finger nails buried in the flesh, and his whole body quivering with agony and benumbed with cold. In this case my pity got the better of my resentment, and I dismounted, pulled him out of the water, and wrapped him in a blanket—for which he seemed very grateful. One of the most touching I saw, were a couple of brothers (boys), both wounded, who had crawled together, and one of them in the act of arranging a heading for the other, with a blanket, had fallen, and they had died with their arms around one another and their cheeks together. But your heart sickens at these details, as mine did at seeing them, and I will cease.

Steve Davis writes from Cumming, Ga.; Bill Hendrick from Marietta. Their University of Tennessee Press book The Atlanta Daily Intelligencer Covers the Civil War is now available.