Howling Wolf memorialized his exploits in vivid and colorful drawings—even while he was imprisoned by the U.S. government.

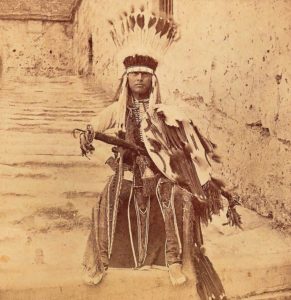

LEDGER DRAWINGS–SO NAMED BECAUSE THEY WERE MADE ON PAGES OF OLD LEDGER or account books—flourished as an art form among the Plains Indians in the second half of the 19th century. The drawings, made with pencil, ink, and watercolor, were a way for warriors to memorialize their deeds. Howling Wolf, a Southern Cheyenne warrior, is considered to be one of the most important ledger-book artists of the era.

Known in his tribe as Honannistto, Howling Wolf fought in its battles with the U.S. Army in the 1860s and early 1870s. He was one of 72 Cheyenne warriors who in 1875 were imprisoned at Fort Marion in Saint Augustine, Florida. And he worked with other Cheyennes to maintain some semblance of traditional life after his release to the Cheyenne reservation in present-day Oklahoma in 1878. He is the only artist known to have made ledger drawings at every stage of this turbulent period in the Cheyenne nation’s history. The subjects of Howling Wolf’s increasingly complex drawings illustrate the change in Cheyenne society from near-constant warfare to externally imposed peace.

Ledger drawings combined the traditional pictographic conventions of Plains art with the new graphic possibilities offered by materials obtained through trading, raiding, or gift exchanges with non-Native settlers. Like the painted buffalo hides, robes, and tipi liners that Plains Indians had long produced, ledger art was rooted in the experience of war. The drawings were part of the war honors system of Plains life, serving as public testimony of personal prowess.

Some warriors did their own drawings; others asked skilled artists to memorialize their exploits in battle, hunting, and horse theft. The aim was to create an accurate and clear account of events. Artists outlined figures in pen or pencil and then applied color, usually in flat tones. They left out backgrounds and other details irrelevant to the events being illustrated; the significance of the various narrative elements shaped proportion and perspective.

Though seemingly simple, ledger drawings convey a great deal of information, placing a warrior’s exploit in the broader context of a raid, battle, or war. Characters are identified by personal glyphs—unique pictographs or symbols to identify them—that float above their heads, typically linked by hairlines. Elements of clothing and adornment also help to identify individuals or the tribes to which they belonged; Pawnee and Osage warriors, for example, have shaved heads and moccasins with flared cuffs. Hooves, footprints, or guns placed at the side of a page indicate how many warriors took part in the event depicted. A series of lines spraying from a gun barrel places the scene in the heat of battle. Weapons floating above the head of an enemy signify that the warrior-hero of the painting disabled his opponent by striking him with his coupstick—an act of supreme bravery among the Cheyenne.

Born in 1849, Howling Wolf fought in the continuous skirmishes that defined Cheyenne life in the final decades of the Southern Plains Wars. He recorded his feats as a young warrior, and those of his fellow tribesmen, in a ledger. Most of the 57 drawings in the ledger illustrate battles and horse raids. He is an active participant in 18 of the battle scenes, all of which include his pictograph: a wolf with lines issuing from its mouth, indicating howls.

The earliest armed encounter Howling Wolf depicts in the ledger is the Sand Creek Massacre. At dawn on November 29, 1864, 675 members of the Colorado volunteer militia attacked a Cheyenne village at Sand Creek, 170 miles southeast of Denver. Adult male warriors of the tribe, taken by surprise, attempted to defend the noncombatants, many of whom fled into the dry streambed of the South Platte River. The soldiers followed, shooting at the retreating Cheyennes. At a point several hundred yards above the village, the Cheyennes dug pits and trenches to protect themselves. The militiamen positioned howitzers on the opposite bank and bombarded the improvised defenses. Over eight hours, they killed roughly a third of the village’s inhabitants—most of them women, children, and men too old to fight. The next day the militiamen returned, set fire to the village, killed the wounded, and mutilated the bodies of their victims, carrying off body parts as ghoulish trophies.

Howling Wolf, who was about 15 years old at the time, depicts the massacre from the perspective of a warrior who helped defend the village. In his ledger drawing he is one of four Cheyennes who gallop across the page from the right; he fires at the militiamen massed along the left border of the page. His companions turn back toward the right edge of the page and fire at unseen enemies behind them. None of the Cheyenne warriors is in full battle garb, reflecting the fact that they were taken by surprise. Hoofprints parallel the movement of the horses from right to left and volleys of arrows line the right edge of the ledger page, together indicating larger numbers of Cheyenne.

Two other drawings from the ledger series illustrate identifiable events in Howling Wolf’s career as a young warrior. The first depicts the action in which he counted coup for the first time: an attack on a wagon train 20 miles away from Fort Dodge, Kansas, in May 1867. Howling Wolf shows himself in the middle of the wagon train. Outnumbered and surrounded by armed gunmen, he unhorses his opponent, but instead of killing him, he strikes him with his coupstick.

The second drawing illustrates an incident the next day. A 75-man war party led by Blackfeet chief Lame Bull attacked another wagon train as it returned to the Cimarron Crossing station on the Arkansas River after delivering government supplies to Fort Union in New Mexico. Howling Wolf was wounded in the thigh as he attempted to cut out the lead mare from the wagon train’s herd. In his depiction of the day’s events, he shows himself fighting singlehandedly against a group of soldiers who emerge at left, guns blazing, as blood spurts dramatically from his wound.

Even in this ledger, which contains his earliest known works, Howling Wolf displays many of the techniques and innovations that distinguished him as an artist. He captures the most intricate details of weapons and costumes with great precision. He explores the possibilities of pencil, colored pencil, crayon, ink, and watercolor to create more-varied color effects than the flat tones in most ledger drawings. He uses traditional pictographic conventions not only to provide information but as art. And he introduces features of landscape and environment not simply as backdrops but as critical elements of the action.

In 1875, reeling from a dry summer, a severe winter, and the U.S. Army’s relentless campaign against them, most of the southern Cheyenne surrendered. The U.S. Army took 72 tribal leaders and warriors as hostages—Howling Wolf among them, along with his father, Eagle Head—and imprisoned them at Fort Marion in Saint Augustine, Florida, so that they could not influence the remaining Cheyenne.

Lieutenant Richard H. Pratt, who was in charge of the prisoners at Fort Marion, ordered their shackles removed and aimed to provide the men with vocational training. He also gave the men sketchbooks, pens, inks, colored pencils, and watercolors and encouraged them to draw. Before long the “Florida Boys” were something of a tourist attraction. Many wealthy northerners wintering in Saint Augustine bought various crafts—bows and arrows, beadwork, and polished sea beans—the Cheyenne prisoners made. Ledger drawings were particularly prized as souvenirs.

During his three years at Fort Marion, Howling Wolf created at least 74 ledger drawings. Only three of them were traditional battle scenes. Perhaps he avoided such scenes while at Fort Marion because his works were intended for tourists, who might have been uncomfortable with scenes of Cheyenne warriors attacking wagon trains and defeating white soldiers. Or perhaps it was because, as a prisoner, he had no new feats of personal prowess to record. Whatever the motivation, most of his drawings from this period depict nostalgic images of everyday life in the camps in the days before the Cheyenne were relegated to the reservation.

While he was imprisoned at Fort Marion, Howling Wolf’s eyesight began to rapidly deteriorate. In 1876 he was sent to Boston for treatment. While there, he learned to speak English and Spanish fluently and abandoned his traditional Cheyenne dress. Howling Wolf returned to Fort Marion the following year, and five months later he and his father were released and sent to the Cheyenne reservation in present-day Oklahoma.

By then Howling Wolf was about 30—the age at which, as the son of a tribal chief and an established warrior in his own right, he would have been recognized as a tribal leader in Plains society. But the traditional paths to power no longer existed. With the influx of white settlers, the near extinction of the buffalo (the primary food source for the Plains Indians), and the outlawing of raids, the Cheyenne struggled to survive. Howling Wolf followed his father’s lead in trying to convert the Cheyenne to the Western ways they had experienced in Florida. After returning to the reservation, he made at least 12 more ledger drawings. Most were camp scenes like those he produced at Fort Marion, but three were strikingly different. In those drawings, instead of recording contemporary events, Howling Wolf explores subjects from tribal history. In a sense they are also an act of public testimony, performed on behalf of the Cheyenne nation as a whole.

After his father’s death in 1881, Howling Wolf gave up the old way of Cheyenne life and worked in various conventional jobs on the reservation. He also grew disillusioned over the federal government’s treatment of the Cheyenne and other Native American peoples. “You gave me the white man’s road and it is very good,” he wrote in a letter to Pratt. “At the fort you gave us cloth[e]s but we have been here one year and they are about all gone.…When I hunted the Bufalo I was not poor; when I was with you I did not want for eney thing but here I am poor. I would like to go out on the planes a gane where I could rome at will and not come back a gain.”

As far as is known, Howling Wolf also stopped drawing. And as drought and starvation ravaged the plains in the 1880s, he reverted to Cheyenne dress and customs and returned to the old ways of a warrior society, becoming a prominent leader of the Cheyenne and working to reclaim tribal land.

Ultimately, though, there was no role for Howling Wolf as either warrior or artist in Cheyenne society on the reservation. In his final years he worked as an Indian dancer in a Wild West show in Houston. He died in a car accident on his way home from Houston on July 5, 1927. MHQ

Pamela D. Toler, who writes about history and the arts, is the author of several books, including Women Warriors: An Unexpected History (Beacon Press, 2019).

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Artists | A Warrior’s Ledger Domain

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!