In the late 1990s, prompted by the popularity of the film Saving Private Ryan and the push to build the World War II Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, the realization that America’s World War II generation was rapidly disappearing entered the nation’s collective consciousness. In virtual panic mode, multiple efforts erupted via websites and other media to capture the wartime stories and accounts of surviving veterans before it was too late.

Today, a generation or more later, the focus on preserving veterans’ memories inevitably has shifted to another vanishing warrior cohort—those who fought our war in Vietnam.

Although approximately 9 million Americans served worldwide on active duty in U.S. military forces during the Vietnam War era (1954-75)—around 10 percent of the corresponding age group—only about 3 million Americans of all military services served in-country in land forces, flew air missions over Vietnam or sailed in the country’s surrounding waters during those years. By 2019, it was estimated that about 775,000 of those 3 million “in-country vets” were still alive. Since then, an average of about 400 have died each day.

Capturing and preserving the first-person accounts of their Vietnam service must be a national priority.

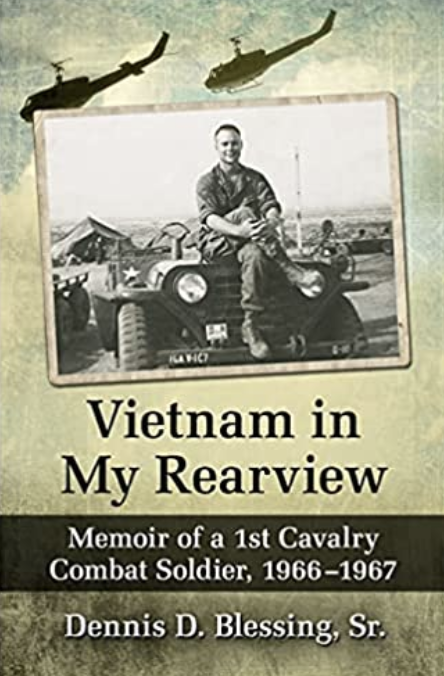

Vietnam War veterans themselves can help in that effort by writing memoirs recounting their service, as Dennis D. Blessing Sr., a combat veteran of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), has done with his concise but engaging new book, Vietnam in My Rearview: Memoir of a 1st Cavalry Combat Soldier, 1966-1967. Importantly, the author begins his account with a very revealing point. There is no “single” Vietnam War experience representing all who served, as Blessing notes:

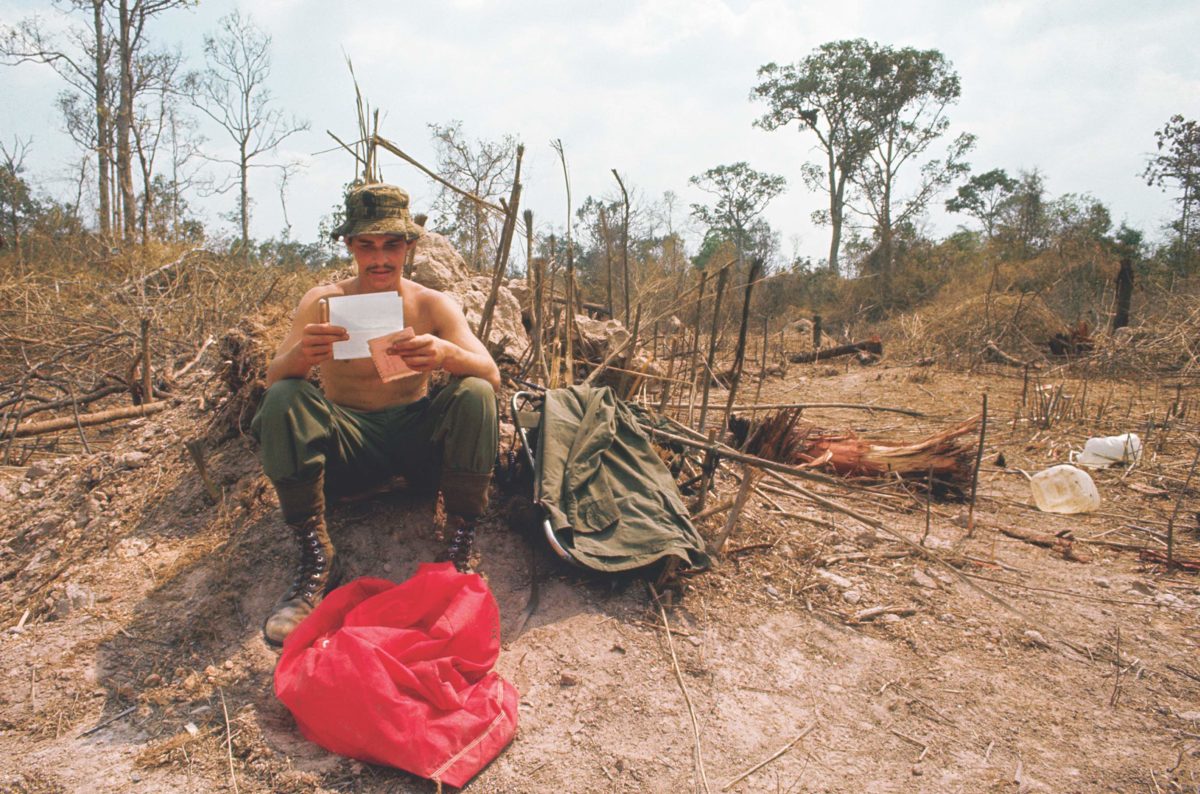

Somewhere, sometime…someone, no doubt, will say: “This guy got it all wrong!” Each American soldier’s experience in this war was different, whether you were humping through the jungle or one of the multitudes of support forces, each of us has his own story…After 54 years since my time in Vietnam I may not have everything exactly right, but this is my story as remembered with the help of my 212 letters home…Writing this book gave me an opportunity to tell the full story of what it was like for me to serve as a combat soldier in an infantry unit in Vietnam…[and]…has helped me in some ways to come to terms with a war I often found hard to understand.

That insightful observation—that no two Vietnam veterans’ experiences were, nor could ever be, exactly the same—is the most profoundly important point that readers should take away from Blessing’s well-written memoir. Aided by his 212 letters home, thankfully preserved, Blessing has published an excellent account of his tour as a combat infantry “grunt” with the 1st Cav. The book provides a snapshot, naturally viewed through his personal lens, of his unit during his 1966-67 tour.

Blessing has done an admirable job of taking readers on his personal “Vietnam War tour.” The very minor errors found by this Vietnam vet in no way detract from his well-written narrative. What he recalled as “Flagstaff” beer was “Falstaff.” His explanation of “left shoulder vs. right shoulder” unit patches was very clear and concise, but he unfortunately got them reversed. The current unit of assignment patch is worn on the left shoulder, while the patch of the unit where one served in combat is worn on the right, not vice versa. However, those are insignificant errors and easily ignored.

The book stands as an articulate and compellingly written example of what Vietnam War vets ought to be striving for: recording their experiences, stories, thoughts and, eventually, efforts to come to terms with the war, their service in it and how it affected their postwar lives.

Blessing included a 15-page glossary of about 300 common terms. Some of them, as all Vietnam vets will recall, come from the Vietnamese language, frequently used by American service members. His list ranges from “Artillery Forward Observer” through “Beaucoup Dinky Dau” (really crazy) and “Sinh Loi” (sorry ’bout that) to “‘Yards” (GI slang for Montagnard tribespeople).

So, come on, Vietnam War vets! Follow Blessing’s outstanding example. Pick up your pens or stubby pencils or computer keyboards and start recording your own Vietnam War experiences…before it’s too late!

Vietnam in my rearview

Memoir of a 1st Cavalry Combat Soldier, 1966-1967

by Dennis D. Blessing, Sr., McFarland, 2021

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.