It used to be easy to define Ulysses S. Grant. He was a heavy drinker who won the Civil War by slinging vast numbers of hapless Union soldiers at the outnumbered Confederacy. But that definition has become more complex. The general’s reputation has been trending upward as recent historians strive to replace the powerful stereotype of the top Union general and two-term president as a butcher commander and failed chief executive. Their collective work has provided a measured and often more appreciative evaluation of the soldier-statesman’s event-filled life and vital legacy.

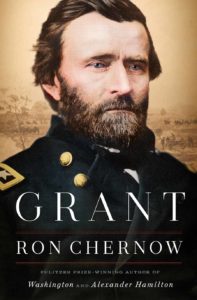

More success has been notched in reevaluating Grant’s military reputation than with his troubled presidential tenure. That too, may be changing. The arrival of Ron Chernow’s Grant and Charles Calhoun’s The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant are brilliant entries to the list of revisionist literature; both deserve a wide readership. The icing on the cake is the publication of the complete annotated edition of The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, edited by John F. Marszalek with David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo.

Best-selling biographer Ron Chernow begins Grant with Walt Whitman’s famous assessment that includes the lines, “What a man he is! What a history!” Chernow proceeds to deliver a dense and riveting saga fully validating the poet’s declaration. Divided into four parts with a total of 43 chapters, Grant covers the Ohio-born and -bred Ulysses’ origins, education and hardscrabble period, his rapid ascent to fame and success as the Union’s top general, his turbulent and influential political career, and his post-presidential years. Chernow threads the narrative with an astute psychological analysis of the man whose private wellsprings remained a mystery. Grant’s relationships with a judgmental father, an undemonstrative mother, and a blowhard father-in-law are examined, yielding rich insights into his experiences with public and private humiliations that wounded him but also added to his strong character. He thrived in a long and happy marriage and was a loving father to four children.

Best-selling biographer Ron Chernow begins Grant with Walt Whitman’s famous assessment that includes the lines, “What a man he is! What a history!” Chernow proceeds to deliver a dense and riveting saga fully validating the poet’s declaration. Divided into four parts with a total of 43 chapters, Grant covers the Ohio-born and -bred Ulysses’ origins, education and hardscrabble period, his rapid ascent to fame and success as the Union’s top general, his turbulent and influential political career, and his post-presidential years. Chernow threads the narrative with an astute psychological analysis of the man whose private wellsprings remained a mystery. Grant’s relationships with a judgmental father, an undemonstrative mother, and a blowhard father-in-law are examined, yielding rich insights into his experiences with public and private humiliations that wounded him but also added to his strong character. He thrived in a long and happy marriage and was a loving father to four children.

Two recurring themes stand out in the book in regard to Grant’s struggles: his alcoholism and his peculiarly naïve and trusting nature. Both tarnished his reputation. Chernow unearths every story (true or false) of Grant’s battles with the bottle. He insists the reader understand that Grant’s rare benders were often preceded by bouts of loneliness, boredom, or pain. It seems that Julia Grant’s presence was the surest guarantee of sobriety and few, if any, lapses were committed during and after his presidency. He judges that “all available evidence suggests Grant had abstained from alcohol and largely vanquished the problem though sheer willpower and perseverance…It was one of the supreme triumphs of a life loaded with major accomplishments.”

Grant’s resolute nature featured perseverance, intelligence, and the patience to pursue victory in the face of innumerable setbacks. This is made manifest in Grant’s willingness to wage war with a remorseless ferocity in the cause of saving the Union, and at the same time demonstrate magnanimity toward the enemy, most famously at Appomattox. While not ignoring serious mistakes, Chernow renders Grant’s military career in the Western and Eastern theaters in refreshingly accessible prose, explaining how this unassuming man delivered the kind of decisive, smashing, aggressive victories at Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and in Virginia that made him a hero in the eyes of his countrymen and brought him to a position of unrivaled power. “Grant was the strategic genius produced by the Civil War,” Chernow proclaims.

Hailed in the postwar North, Grant’s vast popularity and serene confidence, magnified after President Lincoln’s death, propelled him into another level of power and fame. His position as general-in-chief plunged him into the struggles between President Andrew Johnson and the Republican Congress. Grant learned to master the politics of military leadership, but by 1868 he feared that politicians would fritter away the hard-won fruits of Union victory, accepting the Republican nomination with his campaign slogan, “Let Us Have Peace.” The youngest president yet to be elected, the 46-year-old “silent general” won his first term with 53% of the popular vote; in 1872 he swept the Democratic ticket with a huge mandate from the electorate. He remained personally popular during his eight years in the White House; his ardent desire to escape Washington City trumped all considerations of a third term.

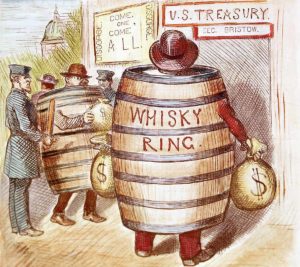

Chernow’s narrative encompasses serious misjudgments, such as Grant’s stubborn loyalty to his corrupt aide Orville E. Babcock in the Whiskey Ring scandal that engulfed his second term. Personally incorruptible, Grant’s trusting nature disinclined him to take action against shady dealings until too late. Notably, Chernow hails the 18th president as an early champion for black civil rights.

Among many other courageous actions, he proudly signed off on the 15th Amendment, broke the spine of the KKK, and tried repeatedly to stop the violent chaos that attended black voting in the South.

Although he lost the battle for a racially enlightened Reconstruction, Chernow writes, “Grant deserves an honored place in American history, second only to Lincoln, for what he did for the freed slaves.”

Grant’s final weeks in office were spent ensuring national authority in the disputed election of 1876, no small achievement. Grant’s financial ruin late in life coincided with his fatal contraction of throat cancer. He rallied to write his memoirs, and in doing so, produced a classic history of the war, ensuring an already indispensable place in U.S. History.

Ron Chernow’s Grant is a masterpiece of the art of biography and will be the standard for some time to come.

Charles C. Calhoun’s The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant is the only comprehensive study of the Grant administration to be published since the 1930s. Calhoun, a distinguished political historian, was determined to rectify this gap, remarking wryly that, “most historical writing magnified its blemishes and slighted its achievements.” To a surprising degree, the hostile charges against Grant levied by his fiercest contemporary critics were embraced and embellished by most 20th-century historians. Here, John Russell Young’s quote is worth repeating: “Calumny has fallen upon the memory of Grant with Pompeiian fury,” he claimed, so that “to tell the truth about him, sounds like unreasoning adulation.”

Charles C. Calhoun’s The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant is the only comprehensive study of the Grant administration to be published since the 1930s. Calhoun, a distinguished political historian, was determined to rectify this gap, remarking wryly that, “most historical writing magnified its blemishes and slighted its achievements.” To a surprising degree, the hostile charges against Grant levied by his fiercest contemporary critics were embraced and embellished by most 20th-century historians. Here, John Russell Young’s quote is worth repeating: “Calumny has fallen upon the memory of Grant with Pompeiian fury,” he claimed, so that “to tell the truth about him, sounds like unreasoning adulation.”

Calhoun’s task is to convince the skeptics, and his meticulously researched book offers a thorough and judicious reassessment of President Grant’s eight years in office. The enormity of Grant’s undertaking in 1868 still astonishes. Buffeted by civil war, assassination, a $2 billion war debt, Johnson’s impeachment, and constant turmoil over “the Southern question,” voters elected General Grant to clean up the disastrous mess created by the nation’s political class. A majority of Northern Americans couldn’t have cared less about Grant’s early fumbling with Cabinet selection, or his friendship with wealthy supporters, or his supposed lack of cultural polish that so outraged professional politicians. Rather, they approved of his first-term achievements in securing financial reform, encouraging a surging economy, promoting humane changes in Indian policy, stabilizing Reconstruction policy, and notching foreign policy triumphs.

These accomplishments were aided by the wise guidance of Cabinet members such as Hamilton Fish, George S. Boutwell, and Amos Ackerman. Reelected by a landslide in 1872, Grant’s second term was marred in 1873 by a severe economic depression, followed by the exposure of corruption in his Cabinet, and Northern white exhaustion with Reconstruction.

The unfolding chapters depict a military hero who became a skilled politician. He lobbied for his agenda, twisted arms, wielded patronage, promoted policies, and shrewdly enlisted supporters in Congress. He did so because he believed the Republican Party was the only national institution that could preserve the war’s goals of union and emancipation. He did so in an atmosphere of vicious, sustained, and shocking attacks by members of his own party led by an unhinged Charles Sumner. Emboldened Democrats launched numerous politically motivated investigations with the goal of destroying the administration.

The firestorm of political venom and visceral hatred directed toward Grant and documented by Calhoun provides shocking reading, and renders his judgment important: “Taken together, Grant’s eight years produced a record of considerable energy and success, tempered at times by frustration and blighted expectations.” Charles Calhoun’s mastery of the inner workings of politics is combined with the unmatched depth of his research. As a result, this important book is not only full of original insights into Grant’s presidency, but also for that of the era’s larger political culture.

Finally, the best place to start a study of Grant can be found in the annotated edition of The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, edited by John F. Marszalek with David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo. Although one might quibble with the editors’ decision not to include maps, the superb annotations make this edition indispensable. Grant’s beautiful narrative of the war is a pleasure to read. While imbued with the spirit of reconciliation between the sections, he also expresses his belief that the North’s cause is the morally superior one. Ulysses S. Grant was the general who saved the Union and the steadfast president who made sure it stayed together. He is surely deserving of a renewed appreciation from the current generation.

Finally, the best place to start a study of Grant can be found in the annotated edition of The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, edited by John F. Marszalek with David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo. Although one might quibble with the editors’ decision not to include maps, the superb annotations make this edition indispensable. Grant’s beautiful narrative of the war is a pleasure to read. While imbued with the spirit of reconciliation between the sections, he also expresses his belief that the North’s cause is the morally superior one. Ulysses S. Grant was the general who saved the Union and the steadfast president who made sure it stayed together. He is surely deserving of a renewed appreciation from the current generation.

A history professor at UCLA, Joan Waugh is the author of U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth (University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

Best Seller

Ulysses S. Grant finished his remarkable memoirs on July 20, 1885, three days before his painful death. Mark Twain had helped his friend find a publisher, and in 1885-86, the initial printing of 200,000 two octavo-sized volumes were sold only by subscription. Salesmen went door to door to increase sales and offered them in four different bindings with price ranges from $7 to $18 a set. Today, in excellent condition, the collectible sets generally sell for $600-$1,800.

Daniel Weinberg

Abraham Lincoln Book Shop, Inc.