Today Paul Fairbrook can freely speak about his time at Camp Ritchie, once known only to World War II intelligence analysts and interrogators as “P.O. Box 1142.”

It’s been said that any well-prepared interrogator, whether in a courtroom or on a battlefield, will strive to ask questions for which he already knows the answers. When it came to the interrogators of the U.S. Military Intelligence Service in World War II, Paul Fairbrook was someone who provided those answers. He was one of the “Ritchie Boys”: mostly young, German-speaking men—many of them Jewish refugees, like Fairbrook—who joined the U.S. Army early in the war and passed through the Military Intelligence Training Center at Camp Ritchie in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Maryland, north of Washington, D.C. Thanks to their native fluency in German, they proved to be ideal interrogators and intelligence analysts. Fairbrook was one of the latter.

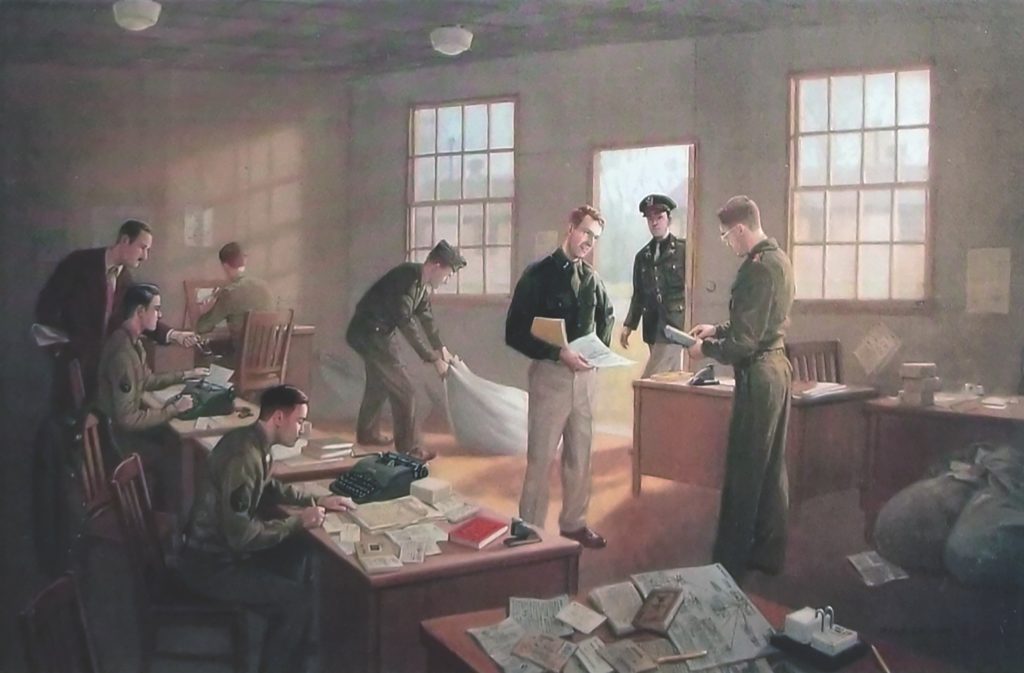

After his four-week course at Camp Ritchie in 1943, Fairbrook was assigned to the War Department’s Military Intelligence Research Section (MIRS) at Fort Hunt, Virginia, about 10 miles south of the Pentagon. Because the activity there was classified, the installation was known only as “P.O. Box 1142.” The job of Fairbrook’s 21-man group was to sort through stacks of captured German documents and create updated editions of a manual, Order of Battle of the German Army—essentially an encyclopedia of the Wehrmacht, detailing specific units, their commanders, their weapons, and their history in combat. There were a series of these color-coded books, each more comprehensive than the last, culminating in the “Red Book” of March 1945. Distributed to U.S. Army units in the field, they provided invaluable information to intelligence officers and prisoner interrogators.

Born Paul Schönbach in Berlin in 1923, Fairbrook arrived in the United States with his family in 1938, after a three-year sojourn in Palestine and a harrowing exit from Europe. Upon his discharge from the army in 1946, he returned to work in the hospitality industry, settling into a two-decade career as food service director at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, where, at the age of 97, he still resides.

Describe the work that you did at MIRS.

The army didn’t have a unit specifically assigned to study captured German documents. The idea was to look at these to help with the tactical aspect of the war, starting with documents that came from North Africa in 1942. I was able to read the documents, German army bulletins, the German military newspapers—the equivalents of Stars and Stripes—anything at all. Our work was specifically to improve books that were already in existence. The U.S. Army had a Wehrmacht order of battle book in 1942, but it was nothing compared to what we came up with. Of course, we didn’t use computers then. That would have made my job so much easier. We put everything on three-by-five-inch cards.

How was the “Red Book” useful to American interrogators in the field?

They could use it as a weapon to interrogate successfully. Before they even started questioning a man, the interrogator could give him the impression that he already knew even more about his subject than the prisoner knew about himself. Using the Red Book, an interrogator could tell a prisoner in German: “I know all about you; I know who your general is; where you’ve been in Russia.” Then the prisoner started talking. That’s where this book came in handy.

What was one of your most important discoveries?

In the fall of 1944, I started running across references in German documents to something called the Nationalsozialistischer Führungsstab (NSF)—the National Socialistic Guidance Staff. It had suddenly become part of the organizational structure of German units. If you look at the Wehrmacht’s organizational structure from the spring of 1944 or before, the NSF is not there. After the failed assassination attempt against Hitler on July 20, 1944, they added the NSF to keep tabs on the loyalty of German officers and troops. Hitler had ordered that at every higher echelon in the Wehrmacht, all the way down to the division level, there would be a loyal Nazi watching the generals. Most of these were probably SS.

Beverley Driver Eddy, the author of the recent book Ritchie Boy Secrets, wrote that your discovery was “central to recognizing that the morale of the German soldier had reached a new low, and used to great advantage by Allied interrogators and psych warriors in the field.”

I told the Pentagon something that they didn’t know. Once I knew about the NSF, I looked for references to it in the German newspapers and the paybooks [the soldbucher, or military identity books] of the German soldiers. I summarized this specific discovery in a 20-page study called “Political Indoctrination and Morale-Building in the German Army.” We got this information out by December 1944, and that was early enough to do some good for the interrogators.

What incoming material surprised you the most?

I was amazed by the foolish German insistence on documenting everything a soldier did. I always joked that if he sneezed, they put it in his soldbuch. Every German soldier had a soldbuch that he carried everywhere he went. The soldbucher were marked with all the units where a soldier had been assigned. They were excellent sources of information.

That sounds very straightforward.

I read in one soldier’s soldbuch that he had gotten the Iron Cross, First Class. There was a stamp bearing the letters and numbers of the unit that had given it to him, and I wrote them down. The next time I had a soldier with an Iron Cross, his soldbuch had the same numbers. At that point I knew that this was the office that gives out the medals. That is one small example of how we connected this information.

How did it feel to be working against the country of your birth?

It felt wonderful. I was 20 years old. I found out shortly later than I had lost part of my family: I’d lost an aunt. I’d lost two lovely young cousins. Once I completed my four-week course at Camp Ritchie, I was automatically made an American citizen. To become a German Jewish American was a feeling I can barely describe.

Did everyone in the Pentagon appreciate your work?

Some of the officers later complained that those of us from Camp Ritchie were a terrible unit because we didn’t have good discipline, that we weren’t really soldiers. But those officers didn’t understand what we were able to do. When you are depending on someone to do research, you can’t force him to stand [at attention], you can’t force him to do research; you have to depend on his intellectual capacity to find things you need to know.

Was it a tight-knit group?

We were really close. When you work on the same things from when I started in September 1943 until V-E Day in May 1945 you become very close. I still remember them all.

What happened to MIRS after the war?

Shortly after V-E Day we were transferred back to Camp Ritchie to become part of a new intelligence unit, the German Military Documents Section. Our job there was to organize all the captured documents. My twin brother Uri, who had earlier broken his leg at Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning, Georgia, had joined our outfit by then, and we spent the remaining time of our military service together. I was discharged on April 21, 1946.

What’s the Ritchie Boys’ legacy?

I think the idea of creating a military intelligence training center to take advantage of anyone who speaks fluent German and to use them for the interrogation of prisoners was a brilliant one. It was a crucial part of the success we had in winning the war, because we had a system that didn’t exist before. It contributed significantly to the Allied success in World War II in Europe. ✯

This article was published in the October 2021 issue of World War II.