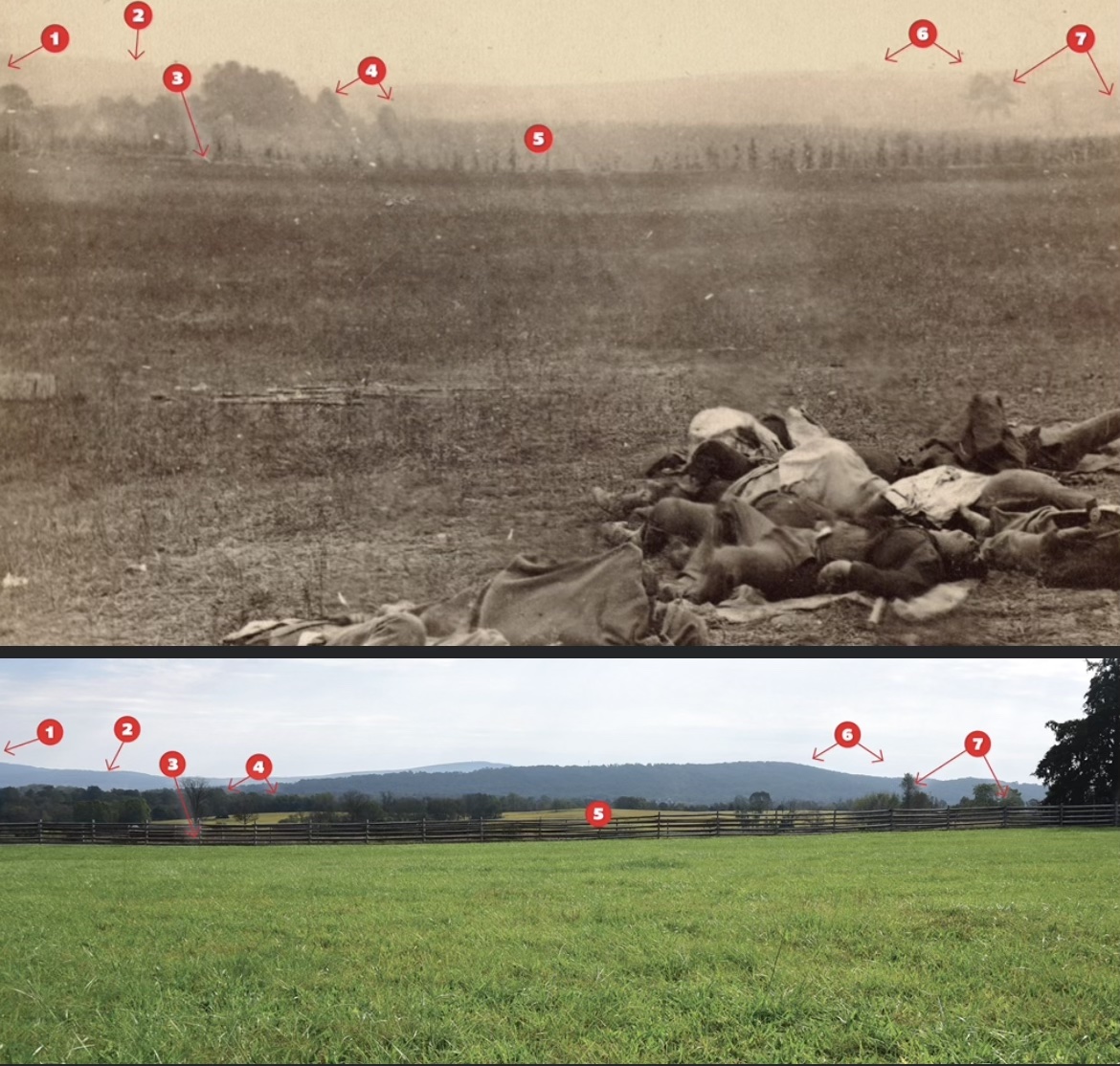

The location of the Antietam battlefield photo above had eluded researchers for years. Who took it and when, however, was well known. Photographers Alexander Gardner and his assistant, James Gibson, both employed by Mathew Brady, took the images on September 19, 1862, two days after the battle. This exposure was one of a series showing dead soldiers and burial parties at work that Brady exhibited in his New York gallery in October 1862. The images shocked viewers, many of whom, far removed from battlefields, still entertained a sanitized view of war.

“Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it,” a New York Times correspondent would write, noting that a “terrible fascination” brought throngs of people to see them.

William Frassanito studied these same images in his 1978 classic, Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day. He was able to ascertain the location of most of Gardner’s images, but this one, stereoview #550, eluded him, mostly due to the photographer’s own caption, “Group of Irish Brigade, as they lay on the Battle-field of Antietam, Sept. 19, 1862.”

Who Were the Irish Brigade?

Recommended for you

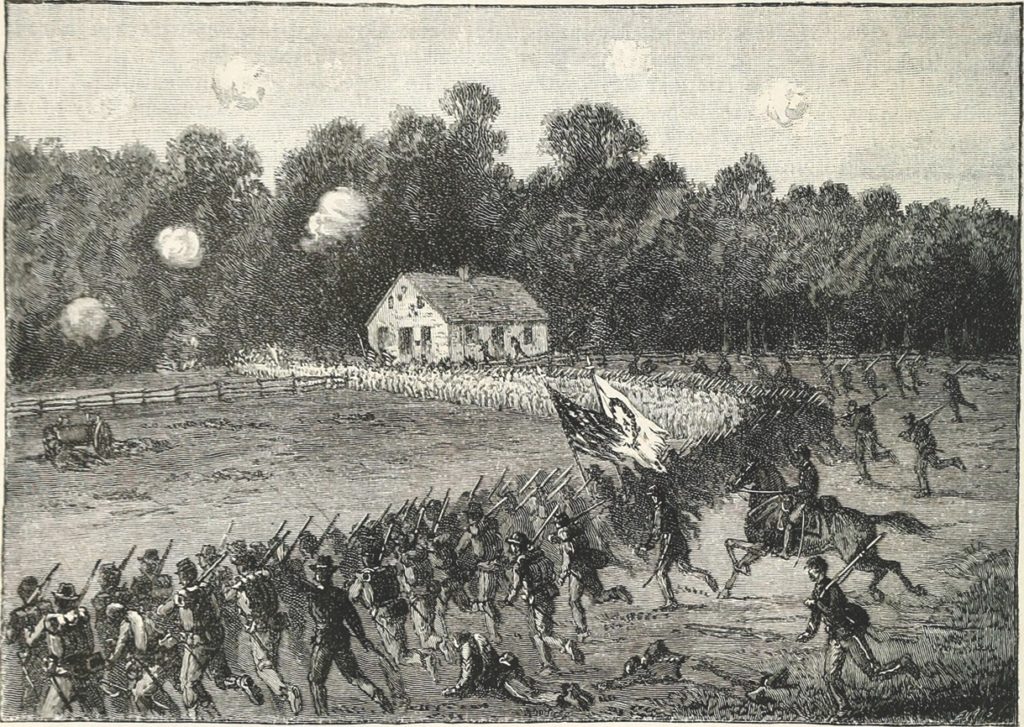

The Irish Brigade served in the 2nd Corps and consisted of the 29th Massachusetts and the 63rd, 69th, and 88th New York Infantry. The storied unit assaulted the Sunken Road on September 17, suffering heavy casualties in the process. But after extensive hunting near the Sunken Road, Frassanito could not pinpoint the image’s location in that vicinity, partially due to the photo’s hazy background.

In findings he published in his 2012 book, Shadows of Antietam, author Robert J. Kalasky was able to track down where the unfortunate soldiers were lying, and extensively documents his photo sleuthing. As can be seen in the following comparative images, Gardner’s camera was located behind the modern visitor center, facing toward Red Hill to the southeast and several yards away from the Mumma Farm Lane that is today paved and used for automobile traffic. The Irish Brigade attacked the Sunken Road about 400 yards to the south.

The location of the image was thus determined, but a mystery remained. Who were these men? Kalasky speculated that they belonged to Maj. Gen. George S. Greene’s 2nd Division of the 12th Corps, who passed over this ground during their late-morning attack toward the Dunker Church and the Hagerstown Turnpike.

The Gardner image in question shows dead Union troops on the Antietam battlefield. That is uncommon in the Gardner series, which mostly shows the bodies of dead Confederates. Federal troops held the field and naturally buried their comrades first. There are a number of keys in the background of the photograph, indicated by the numbers below, that help locate its position. When the relative location of the Gardner image is juxtaposed with the mass grave of the 20th New York that cartographer Elliott placed in this nearly same location, it is not far-fetched to conclude these corpses were men of that regiment. The jumbled forms have been placed on shelter tents and blankets so that burial parties could drag them to this central location for burial, and as they were going about their morose work when Gardner was taking his images, other dead men could have been dragged here. It’s sobering to think that these men who gave their life for their country are a drop in the bloody bucket of Antietam’s 23,000-plus casualties, and that they may now rest in unmarked graves in Antietam’s National Cemetery.

Key:

1. Roulette house out of sight to the left

2. Portions of South Mountain visible through the haze

3. Mumma Farm lane, the modern

park road

4. Trees separating Roulette Farm fields

5. Site of Mumma’s wartime cornfield

6. “Bump” sloping to “notch” in Red Hill

7. Trees along Roulette Farm lane

A new Clue

The discovery of new historical primary documents is always exciting. In the spring of 2020, Andrew Dalton and Timothy Smith of Pennsylvania’s Adams County Historical Society came across a long-forgotten map at the New York Public Library that marked battlefield burial trenches and individual grave sites of thousands of Union and Confederate soldiers killed at the Battle of Antietam. Drafted in 1864 by cartographer Simon G. Elliott, the detailed map locates 2,644 Union and 3,210 Confederate graves. Dashes on the map indicate Confederate locations, while Federal graves are identified by crosses. Dead horses were marked by figures resembling commas. The Union bodies were exhumed in 1866 and relocated to the Antietam National Cemetery, and the Confederates were eventually reinterred at Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown.

The map was a revelation for students of Antietam, and has a direct bearing on the photograph in question. Very close to the spot where Gardner’s “Irish Brigade” photo was taken, Elliott shows a mass grave of 20 soldiers from the 20th New York. Considering the fact that Colonel Irwin’s 6th Corps brigade attacked over this very ground and suffered a staggering 51 killed, it is very plausible to conclude that the dead soldiers pictured belonged to the 20th New York, shot down during their assault.

Why would Gardner have labeled these men as “Irish Brigade” dead? There are a couple of possibilities. He might have been told the dead men were from New York, and not knowing exactly where the Irish Brigade attacked, he made his erroneous conclusion. The Elliott Map labels the Mumma Farm Lane as “Rebel Works.” Today, the “Sunken Road” refers to a specific location, but when the photographers reached the battlefield, the nomenclature would not have been as precise. It’s possible that Gardner did not know exactly where the Sunken Road began and ended.

Or he could have labeled the men as casualties from the well-known Irish Brigade as a marketing ploy. Gardner wanted to make money on his images, and wasn’t beyond manipulating the facts to make a buck, as he would prove in 1863 when he dragged a Confederate “sharpshooter” to his Devil’s Den lair at Gettysburg.

Who Were the Men in This Photograph at Antietam?

Over the past decades diligent research has pinpointed the location of this image of Antietam’s grim harvest. And now, by correlating the information on the Elliott Map with the location of the image, I believe that the dead men were members of the 20th New York who had been dragged to a central location for mass burial. While that cannot be stated with 100 percent certainty, the case is certainly strong.

The conclusion that the dead men are from the 20th New York rests with Civil War Times, but we would like to thank Chris Vincent and the Antietam Institute, Thomas G. Clemens, and the Center for Civil War Photography for their assistance with this article.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.