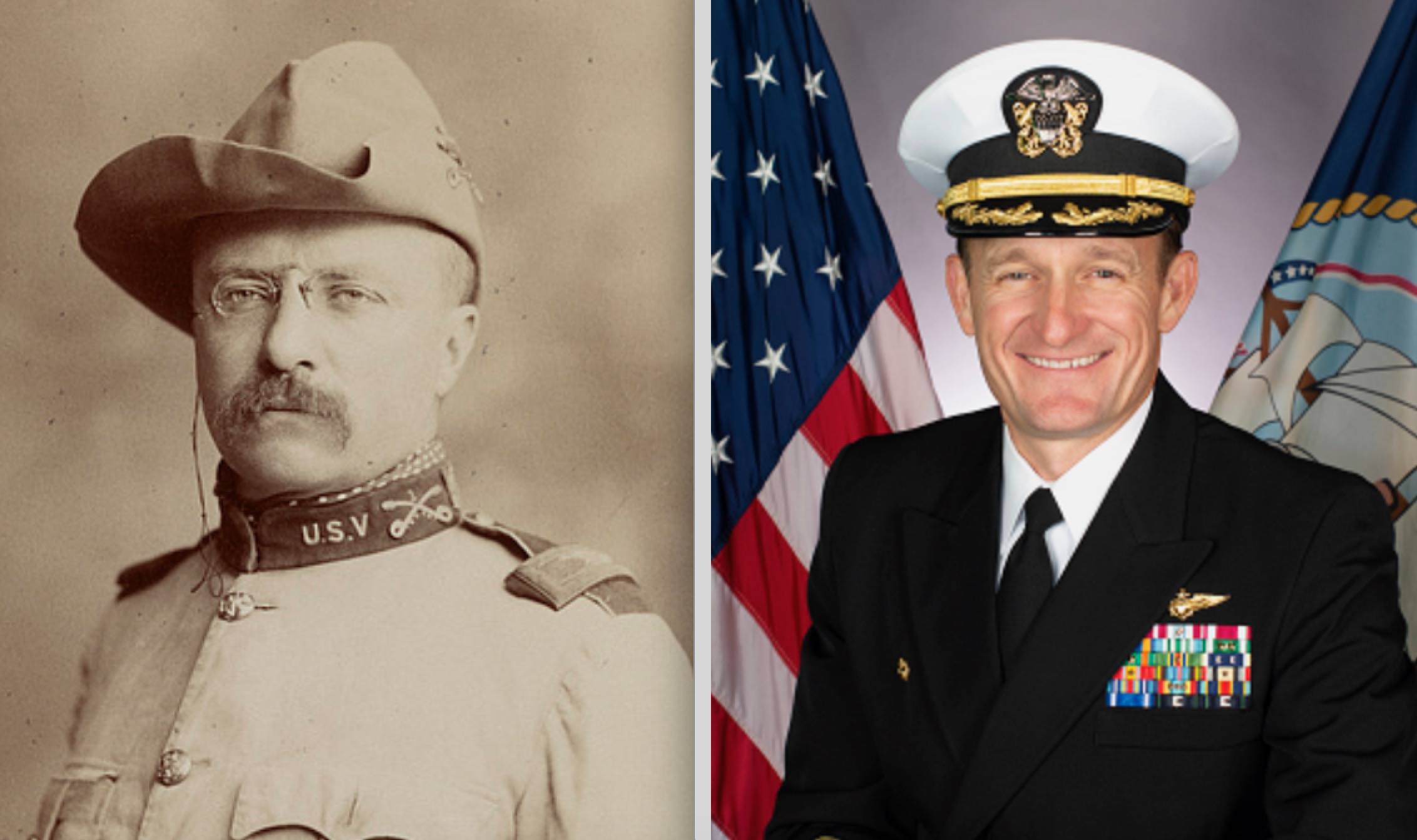

Navy officials are finding themselves in controversial waters in the wake of Thursday’s announcement that the service was relieving Capt. Brett Crozier of his command of the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt, a decision made following the leak of a four-page letter Crozier penned pleading for U.S. assistance to help stymie the spread of COVID-19 on the 4,800-person ship.

“This will require a political solution but it is the right thing to do,” Crozier wrote in the letter, which was first obtained by the San Francisco Chronicle. “We are not at war. Sailors do not need to die. If we do not act now, we are failing to properly take care of our most trusted asset — our Sailors.”

Crozier’s letter was sent via a “non-secure, unclassified” email that included at least “20 to 30” recipients in addition to the captain’s immediate chain of command, Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly told reporters Thursday.

It was an act that “raised alarm bells unnecessarily,” Modly said. “It undermines our efforts and the chain of command’s efforts to address this problem, and creates a panic and this perception that the Navy’s not on the job, that the government’s not on the job, and it’s just not true.”

Crozier’s firing sparked a maelstrom of criticism, with a mother of one Roosevelt sailor telling Navy Times she was “devastated” by the captain’s dismissal, adding that Crozier “risked his own livelihood. That is so hard to do. Not a lot of men, not a lot of women, not a lot of people out there who would do that for others.”

Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that the aircraft carrier’s namesake was once entangled in a similar conundrum, noted retired Navy commander Ward Carroll in Proceedings Magazine.

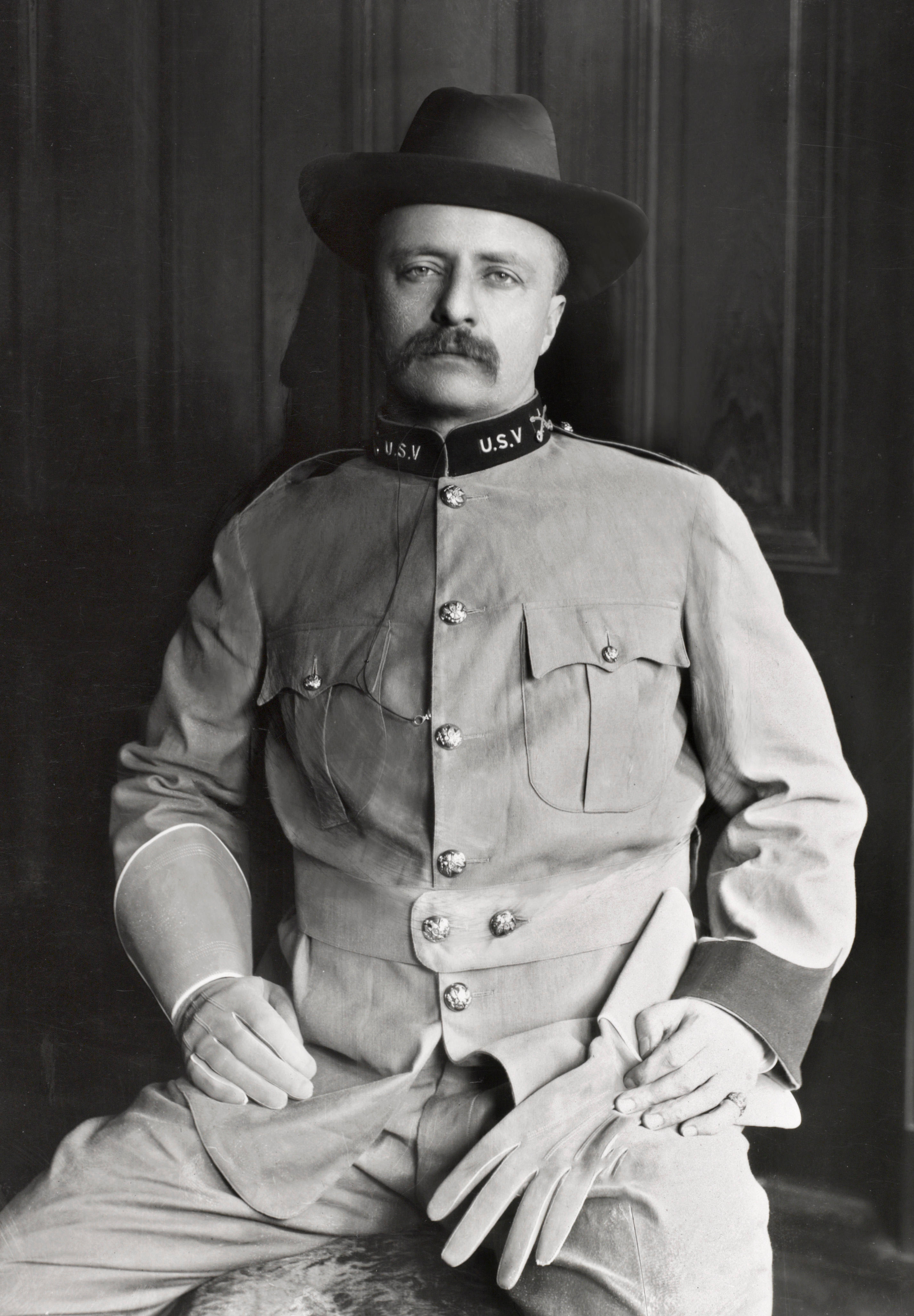

As the Spanish-American War drew to a close in the summer of 1898, the Santiago de Cuba-based men of the U.S. Army Fifth Corps — Colonel Theodore Roosevelt and his famed Rough Riders among them — encountered one of their toughest challenges yet: malaria and yellow fever.

In all, nearly 4,000 of the 4,270 men in Fifth Corps would contract severe illnesses. Many were on the verge of death.

“The soldier who storms the heights and wins them is a hero in the world’s eyes,” war correspondent Kit Coleman wrote from the troop transport ship SS Comal, a vessel tasked with ushering the ill soldiers to Florida. “Uncle Sam’s boys did that; but far more to the credit of the American soldier is the uncomplaining way in which he bore that which was inflicted by the blundering of his own people.”

Rife with disease, “the eight divisional commanders, including Roosevelt, were convinced that if they remained in Cuba, Fifth Corps would be wiped out,” Carroll writes.

The dire situation prompted senior officers to meet with Maj. Gen. William R. Shafter, commander of the Fifth Corps, to recommend that troops be withdrawn from Cuba posthaste. That result of that meeting — whether Shafter agreed or not — remains unknown.

Regardless of the outcome, the commanders were compelled to put their request into writing –– a task that fell to Roosevelt because, as the only non-general among the senior officer group, had less to lose career-wise. The eventual U.S. president drafted what is now known as the infamous Round-Robin Letter:

MAJOR-GENERAL SHAFTER. SIR: In a meeting of the general and medical officers called by you at the Palace this morning we were all, as you know, unanimous in our views of what should be done with the army. To keep us here, in the opinion of every officer commanding a division or a brigade, will simply involve the destruction of thousands.

There is no possible reason for not shipping practically the entire command North at once. Yellow-fever cases are very few in the cavalry division, where I command one of the two brigades, and not one true case of yellow fever has occurred in this division, except among the men sent to the hospital at Siboney, where they have, I believe, contracted it. But in this division there have been 1,500 cases of malarial fever. Hardly a man has yet died from it, but the whole command is so weakened and shattered as to be ripe for dying like rotten sheep, when a real yellow-fever epidemic instead of a fake epidemic, like the present one, strikes us, as it is bound to do if we stay here at the height of the sickness season, August and the beginning of September.

Quarantine against malarial fever is much like quarantining against the toothache. All of us are certain that as soon as the authorities at Washington fully appreciate the condition of the army, we shall be sent home. If we are kept here it will in all human possibility mean an appalling disaster, for the surgeons here estimate that over half the army, if kept here during the sickly season, will die.

This is not only terrible from the standpoint of the individual lives lost, but it means ruin from the standpoint of military efficiency of the flower of the American army, for the great bulk of the regulars are here with you. The sick list, large though it is, exceeding four thousand, affords but a faint index of the debilitation of the army. Not ten per cent are fit for active work.

Six weeks on the North Maine coast, for instance, or elsewhere where the yellow-fever germ cannot possibly propagate, would make us all as fit as fighting-cocks, as able as we are eager to take a leading part in the great campaign against Havana in the fall, even if we are not allowed to try Porto Rico. We can be moved North, if moved at once, with absolute safety to the country, although, of course, it would have been infinitely better if we had been moved North or to Puerto Rico two weeks ago. If there were any object in keeping us here, we would face yellow fever with as much indifference as we faced bullets. But there is no object.

The four immune regiments ordered here are sufficient to garrison the city and surrounding towns, and there is absolutely nothing for us to do here, and there has not been since the city surrendered. It is impossible to move into the interior. Every shifting of camp doubles the sick rate in our present weakened condition, and, anyhow, the interior is rather worse than the coast, as I have found by actual reconnoissance.

Our present camps are as healthy as any camps at this end of the island can be. I write only because I cannot see our men, who have fought so bravely and who have endured extreme hardship and danger so uncomplainingly, go to destruction without striving so far as lies in me to avert a doom as fearful as it is unnecessary and undeserved.

Yours respectfully, THEODORE ROOSEVELT, Colonel Commanding Second Cavalry Brigade.

Signed by all the officers, the letter was delivered to Shafter and meant for delivery to the Army Headquarters in Washington.

Perhaps fearing inaction on the side of Shafter, a copy of the letter also found its way to an Associated Press correspondent – allegedly at the hands of Roosevelt — who cabled immediately to AP headquarters.

The letter was published that same day on August 4.

When the news broke stateside, President William McKinley was indignant, requesting that “every possible effort [be] made to ascertain the name of the person responsible for its publication.”

McKinley was close to concluding peace negotiations with Spain and sought to maintain a military presence in Cuba until that end was achieved. He was cognizant, however, that public sentiment would turn against him if he kept the troops in Cuba. To counteract the effect of the Round-Robin Letter, the men of the Fifth Corps were hastily recalled to Long Island, New York.

Secretary of War Russell A. Alger insisted the letter had nothing to do with the return of the Fifth Corps, “however, [Alger] was on record as previously having asserted that no ships were available” to transport the men back from Cuba, Carroll notes in Proceedings.

Similar to Modly’s press conference Thursday, Shafter decried the leak, saying, “it would be impossible to exaggerate the mischievous and wicked effects of the ‘Round Robin.’ It afflicted the country with a plague of anguish and apprehension.”

In his memoir, “The Rough Riders,” Roosevelt offers a contrasting perspective, stating that keeping the Army “in Santiago meant its entirely purposeless destruction.”

In going over the heads of his immediate chain of command, Roosevelt’s leaked letter to the Associated Press was eventually credited with cutting through the red tape of bureaucracy and saving the lives of 4,000 men.

Despite the hasty dismissal of Capt. Crozier, the large crowd of Theodore Roosevelt sailors who gathered Thursday to chant his name and cheer as he departed the hulking ship for the last time may indicate how fondly the skipper’s actions will be viewed in the years to come.

Military Times editor J.D. Simkins contributed to this report.