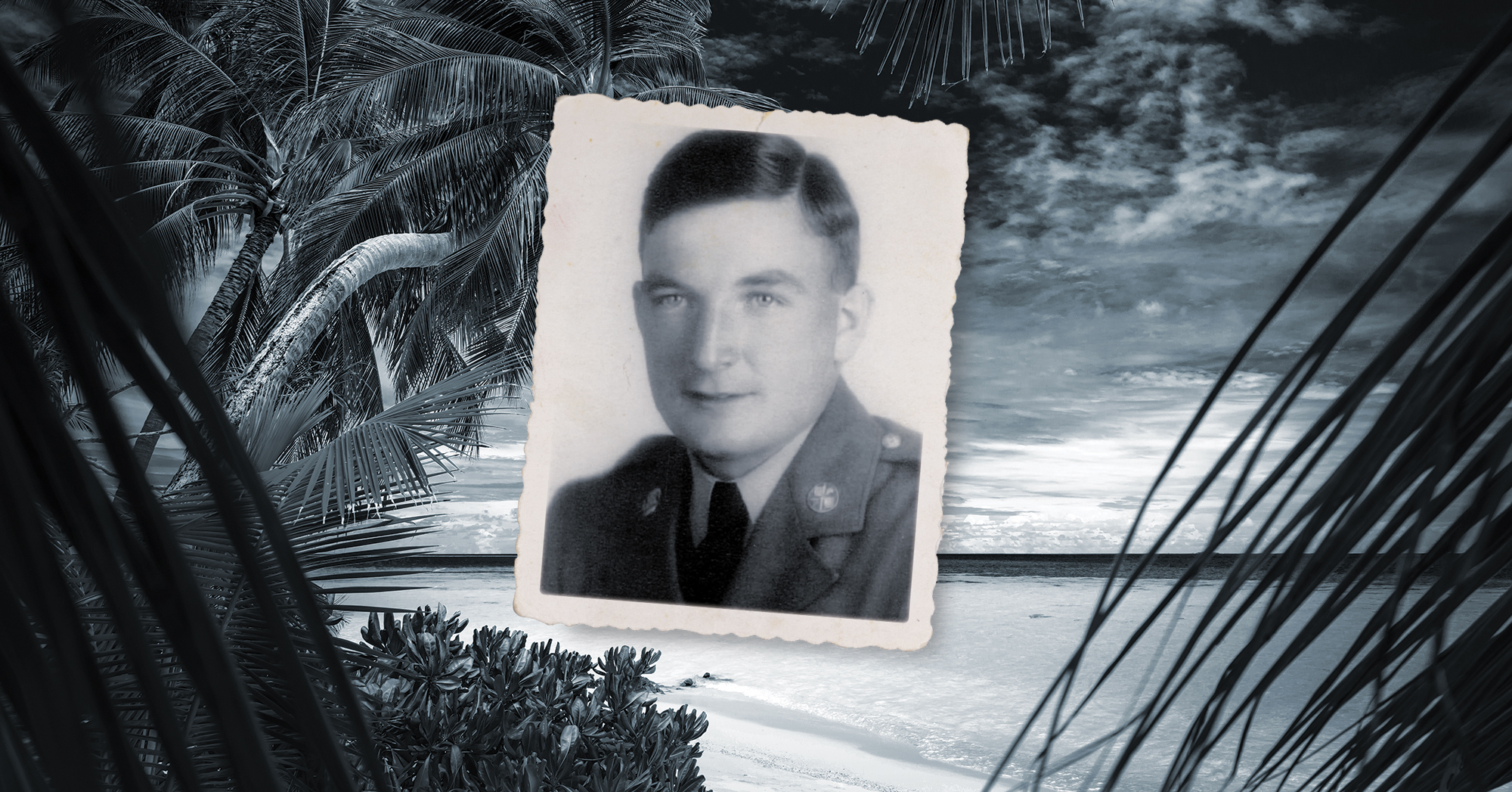

During World War II, young American cattle rancher Franklin Nash served as a member of Australia’s covert Coastwatchers

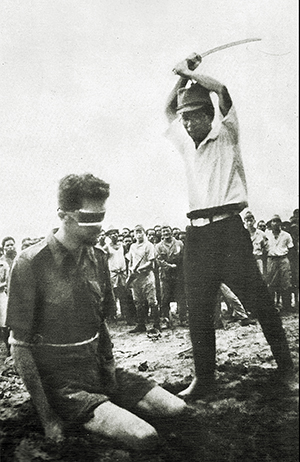

There were far safer assignments during World War II than hiding amid tropical rainforests on Japanese-occupied islands to spy on the enemy and radio information to Allied intelligence. Capture was an all-too-real possibility and would spell certain torture and death. But that was precisely the duty for which some 800 Australians volunteered. Known as Coastwatchers, they were arguably the most vital yet unsung heroes of the Pacific War. Among their number was a lone American GI.

The story of how Benjamin Franklin Nash—Franklin, to family and friends—came to spend more than two years observing and reporting on Japanese activities from behind their lines would doubtless make for a thrill-a-minute film. Three decades after war’s end a pair of veterans who had served with Nash in the South Pacific exchanged letters in which they reminisced about their friend and fellow soldier. “I remember Frank Nash expressing a desire to get into coast watching,” wrote one, “and I figured the guy must be stark raving mad. It was bad enough at [Guadalcanal], but to consider operating a radio from Japanese territory seemed suicidal.”

“He was a real hero,” replied the other veteran, a retired colonel. “When I heard what he wanted to get into, I thought he must be out of his mind.…My hat is off to him.”

The role of the Coastwatchers was fraught with imminent danger. It required daring men willing to set up observation posts on occupied islands teeming with enemy troops to observe their sea, land and air buildup and dispositions, then transmit coded intelligence in the open. Based on their information, planners would create lists of viable targets for Allied ships, fighter planes and dive-bombers. If that weren’t dangerous enough work, the Coastwatchers also took responsibility for rescuing downed airmen and shipwrecked sailors.

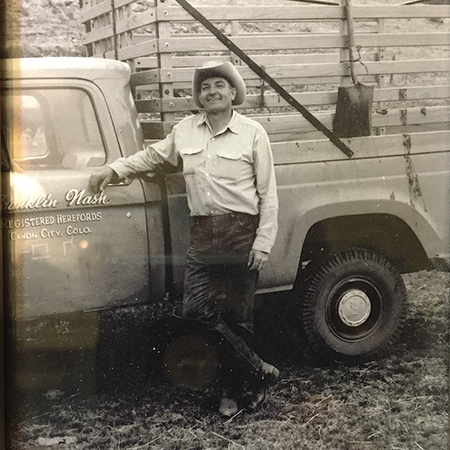

At first glance Nash seemed an unlikely candidate for such a group. The lanky, laconic 6-foot-2-inch Coloradan was a third-generation cattle rancher, a member of a family that raised registered Hereford cattle on a 40,000-acre spread his father and grandfather had started as a homestead in the late 1800s. Young Franklin was virtually raised in the saddle. “He lived what the John Wayne movies only show,” daughter Julie Nash says. “He was the guy who really rode the horse and gathered the cattle, and he did it better than anyone.”

Nash took time off ranching to study geology at the University of Colorado in Boulder and was in his sophomore year in December 1941 when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The 23-year-old immediately left school and enlisted in the Army.

“He lived what the John Wayne movies only show,” daughter Julie Nash says. ‘He was the guy who really rode the horse and gathered the cattle, and he did it better than anyone.”

It turns out that Nash had long been preparing for life in the military. While a student at Cañon City High School he’d completed three years of Junior ROTC training, working his way up from cadet private to captain, commanding one of the cadet companies and serving as battalion adjutant. According to another daughter, Harriet Holloway, he also accumulated “a collection of medals…as a sharpshooter” on the ROTC rifle team. While in college Nash had joined the Colorado National Guard.

The young recruit was assigned to a signal company in California, where the Army put his marksmanship skills to use training other recruits to shoot. When it appeared he might spend the war stateside, he pressed superiors for a combat assignment. “I guess the commander figured he was serious,” Harriet says, “as they finally shipped him out to the South Pacific.”

Corporal Nash was assigned as a radio operator to the 410th Signal Company (Aviation), initially stationed in the New Hebrides (present-day Vanuatu). In January 1943 the 410th moved to Guadalcanal, in the Solomon Islands, where Nash helped install and operate the first Allied radio control tower at Henderson Field, a vital and hotly contested airstrip recently wrested from the Japanese.

Less than a month after arriving on “the Canal,” Nash found the action he’d been seeking. A letter of commendation signed by Lt. Gen. Millard F. Harmon records how the young American performed. “Rather than exercise your privilege of seeking shelter when Japanese bombers attacked Henderson Field,” it states, “you remained at your post in the control tower to keep airplanes notified of conditions at the field and to direct the takeoff of departing aircraft.” One pilot radioed his plane was low on fuel, whereupon Nash “brought it safely in during the most violent part of the engagement.” His actions earned him the Bronze Star, the first of several awards and commendations he would amass by war’s end.

While serving with the 410th, Nash learned of the Coastwatchers, an organization of Royal Australian Navy (RAN) volunteers who set up posts on enemy-held South Pacific islands to report on Japanese movements. These were not professional military men. “The watchers appointed by the navy,” recalled Lt. Cmdr. Eric Feldt, wartime director of the Coastwatchers, “were generally postmasters, harbormasters, schoolteachers, police or railway officials—people who had at hand the means of passing information by telegraph.”

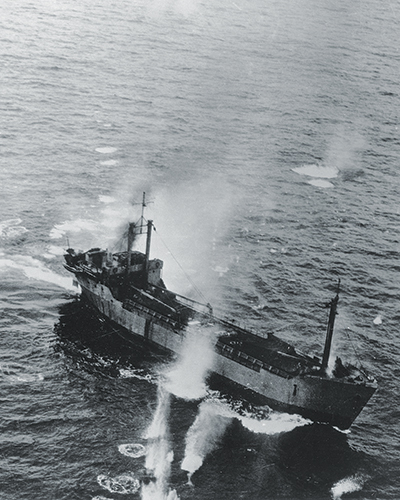

The Coastwatchers’ forward station, call letters KEN, was on Guadalcanal. As a radio operator, Nash was privy to accounts of their dramatic sea rescues of downed aviators and shipwrecked sailors, as well as transmissions that warned of Japanese troop movements and enabled the interception and sinking of countless enemy vessels.

Operating singly and in pairs, the Coastwatchers had infiltrated the broadleaf forests of the Solomons, working closely with friendly natives while seeking to avoid those with Japanese sympathies. To avoid detection they kept moving from one barely accessible location to another, shouldering heavy equipment that included the radio set, a 70-pound generator and a five-gallon can of fuel.

Operating singly and in pairs, the Coastwatchers had infiltrated the broadleaf forests of the Solomons, working closely with friendly natives while seeking to avoid those with Japanese sympathies

Nash was instantly smitten with their mission. This was precisely the sort of action that appealed to him, and he wanted in. He later told an interviewer the prospect of spying on the enemy and reporting their activities “intrigued the hell” out of him. But a few significant obstacles stood in his way.

For one, South Pacific rainforests bore no resemblance to the cattle country of south-central Colorado. Second, the Yank had no training or experience in the type of clandestine warfare practiced by the Coastwatchers. Third, and perhaps the deal-breaker, he was not a member of the Australian military.

Nash was undeterred. “When he made up his mind to do something,” son Clint recalls, “nothing would stop him.” On learning the 410th Signal Co. was moving to the rear, Nash visited Station KEN and volunteered his services.

Lt. Cmdr. Hugh Mackenzie, Feldt’s deputy, happened to need a good radio operator and agreed to put the eager American to work, providing he apply for temporary reassignment from the U.S. Army to the RAN. After sending the relevant paperwork and waiting for a predictably slow response, an impatient Nash chose to reassign himself. “I sort of deserted,” he recalled. The transfer papers eventually arrived, officially loaning the young Coloradan to the Coastwatchers.

Taking on Nash proved an inspired decision. A memorable American character in the 1963 war film The Great Escape was nicknamed “the Scrounger” for his uncanny ability to procure hard-to-find items. He had nothing on Nash. As irregulars the Coastwatchers often ran short of supplies and provisions. Their new Yank colleague was an answer to their prayers, for Nash always seemed able to beg, borrow, steal or simply build what they required.

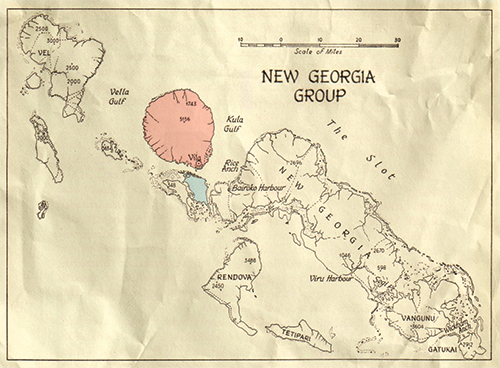

In early May 1943 the brass at Station KEN decided to send a man to assist RAN Sub-lieutenant Arthur Reginald “Reg” Evans, a wiry and resourceful Coastwatcher. Working with a network of natives he employed as scouts, spies and bearers, Evans had set up a one-man observation post high on the small volcanic island of Kolombangara, just east of New Georgia in the Solomons. From his perch he watched the comings and goings of enemy shipping as thousands of Japanese soldiers built an airstrip below him. His radio reports to air strike command regarding enemy shipping had already cost the Japanese dearly, and traffic had picked up in his sector.

In early May 1943 the brass at Station KEN decided to send a man to assist RAN Sub-lieutenant Arthur Reginald “Reg” Evans, a wiry and resourceful Coastwatcher. Working with a network of natives he employed as scouts, spies and bearers, Evans had set up a one-man observation post high on the small volcanic island of Kolombangara, just east of New Georgia in the Solomons. From his perch he watched the comings and goings of enemy shipping as thousands of Japanese soldiers built an airstrip below him. His radio reports to air strike command regarding enemy shipping had already cost the Japanese dearly, and traffic had picked up in his sector.

Nash jumped at the chance to help Evans. Mackenzie overcame his initial reluctance, and in mid-May, after Nash completed a three-day crash course in jungle survival, natives delivered the young American to Kolombangara in a dugout canoe. He and Evans hit it off immediately, and Nash could not have had a better mentor. The older man had an uncanny ability to adapt to his surroundings and a knack for recognizing and reporting important enemy developments. A few months after Nash’s arrival on the island the teammates were peripherally involved in a rescue operation with future international ramifications.

Blackett Strait, the narrow channel flowing between the south coast of Kolombangara and the north end of neighboring Arundel, proved an ideal supply route for the Japanese, the number of enemy warships and barges conveying troops and supplies through the strait steadily increasing. To counter the enemy buildup, Evans and fellow Coastwatchers reported on the types, numbers and location of enemy aircraft and vessels, whereupon U.S. bombers, fighter planes and PT boats searched for viable targets. Meanwhile, the Coastwatchers maintained a lookout for fliers and seamen whose vessels had crashed or sunk.

On the moonless night of August 1–2 Evans and Nash spotted a sudden eruption of flames against the inky black sea and sky. It was obviously the funeral pyre of a vessel, but it was impossible to tell whose. Nash radioed their intention to scour the coastline for survivors. The next morning the pair spotted wreckage in mid-channel, but their search yielded no results.

On the moonless night of August 1–2 Evans and Nash spotted a sudden eruption of flames against the inky black sea and sky. It was obviously the funeral pyre of a vessel, but it was impossible to tell whose

Shortly thereafter a PT boat was reported missing and presumed sunk, its crew lost. Nearly a week later, however, after a heroic effort in which the young lieutenant commanding the vessel managed to drag or lead ashore 10 of his 12 crewmen, a pair of Evans’ native scouts reported having encountered the shipwrecked sailors on a nearby island.

Evans immediately sent a half dozen native paddlers in a supply canoe along with a note:

To Senior Officer…Have just learned of your presence on Naru Is.…Strongly advise you return immediately to here in this canoe, and by the time you arrive here I will be in radio communication with [American] authorities at Rendova, and we can finalize plans to collect balance of your party.

The lieutenant followed the Coastwatcher’s instructions, hiding beneath palm fronds as natives paddled the canoe, and the two soon met, whereupon Evans invited the young American into his tent for tea. The skipper of the wrecked vessel was Lt. John Fitzgerald Kennedy (the future 35th U.S. president), his boat the soon-to-be-legendary PT-109. To the Coastwatchers he was just another shipwrecked sailor in need of help. An American patrol boat soon picked up Kennedy from Kolombangara, then retrieved his crew.

Under Reg Evans’ tutelage Nash was a quick study, and given the course of events in the Solomons, he would have to be. Immediately after Kennedy’s rescue, Evans relocated to nearby Gomu, leaving his American partner the sole Allied presence on Kolombangara—with several thousand Japanese to keep him company.

As the Solomons campaign heated up, the Allies and Japanese engaged in a massive game of maritime chess. The Allies had initiated their island-hopping strategy of bypassing and isolating various enemy strongholds, forcing the Japanese to hurriedly evacuate troops from bases that were no longer viable. For such operations they required a steady stream of barges and other vessels. From his observation post on the Kolombangara heights Nash radioed their movements to Evans, who relayed the intelligence to direct Allied air strikes. When the Japanese evacuated Kolombangara, Nash moved his equipment to Gomu, where he joined Evans’ replacement, Forbes Robertson.

When life on Gomu proved uneventful, the pair closed up shop and headed for the Coastwatchers’ advance base on Munda. There Nash received orders to scout Mono, one of the Treasury Islands, in preparation for an Allied landing. Existing intelligence was long outdated, thus it fell to the young American to accurately determine the enemy presence.

‘S/Sgt. B.F. Nash…has carried out extensive patrols and scouting missions in enemy territory, accompanied only by natives, for the purpose of gathering intelligence and organizing guerrilla warfare against the Japanese. Many of his patrols yielded valuable information and resulted in the killing and capture of numerous Japanese’

On the night of October 21–22 Nash and three teammates paddled a mile from a PT boat to a beach only a short distance from a village, whose residents fortunately proved friendly. A rumor had circulated at Station KEN that downed American airmen had made their way to Mono and were living in the bush. As Nash and his men soon learned, the rumors were true. Three airmen had been shot down that June. The wind and ocean currents had propelled their raft to Mono, where the trio had spent the intervening months. Four more downed American fliers had joined them on the island, only to take their chances in a dugout canoe. Meanwhile, hundreds of Japanese troops fleeing the Allied advance swarmed onto Mono, making the remaining castaways’ position ever more precarious. After assessing the situation on the ground, Nash arranged a rendezvous with a PT boat and returned to base with both accurate intelligence and the rescued airmen.

Although the Solomons were being liberated one by one, Nash was far from finished with his service as a Coastwatcher. The New Guinea campaign was going full tilt, and on November 1 the Allies landed in force at Torokina, a coastal village on the south side of heavily occupied Bougainville. Before any of the thousands of troops hit the beach, a half dozen Coastwatchers, including Nash, had landed to observe the enemy.

“Our basic job on Bougainville,” Nash recalled, “was to go up in the bush and keep an eye on the Japs so they wouldn’t come back down while we built an airstrip at Torokina. There was a lot of Japs left on Bougainville.…We had to be prepared at a moment’s notice.” The Japanese did, indeed, try to take the airbase. “They didn’t get it done,” Nash said succinctly.

Given a precious month’s leave in Australia, a restless Nash inquired about working on a cattle ranch. “A guy told me if I wanted to go to the backcountry, I could find work,” he recalled. “I took a train to the interior and got back to ranchin’ for a while, workin’ with horses and cattle.” When his leave was over, he got back to work in Bougainville, helping to guide dive bombers and supply planes to the new airstrip.

By definition the Coastwatchers were strictly observers and information gatherers; combat was not a part of their mandate. “It was not their duty to fight and thus draw attention to themselves,” Feldt recalled. “It was their duty to sit, circumspectly and unobtrusively, and gather information.” There were occasions, however, when contact with the enemy was unavoidable. Jesse Scott, one of the airmen rescued from Mono, alluded to that in a letter to Nash’s parents. “[He has] saved a lot of us fliers,” Scott wrote, “as well as taking care of a few of the…Japs himself.”

A 1945 letter of commendation from Lt. Gen. Stanley G. Savige, the Australian commander who accepted the Japanese surrender on Torokina, detailed Nash’s interactions with the enemy. It referenced the Coloradan’s “forest craft, courage, initiative [and] leadership,” adding, “S/Sgt. B.F. Nash…has carried out extensive patrols and scouting missions in enemy territory, accompanied only by natives, for the purpose of gathering intelligence and organizing guerrilla warfare against the Japanese. Many of his patrols yielded valuable information and resulted in the killing and capture of numerous Japanese.”

In letters home Nash happily discussed the family cattle business. But he was markedly silent regarding the nature of his service—largely due to its secret nature, of course, but perhaps also to avoid alarming his parents.

In December 1945 Nash was honorably discharged from the Army at the rank of technical sergeant. In addition to the Bronze Star and his letters of commendation, he carried home medals and citations from the United States, Britain and Australia. These included the U.S. Legion of Merit, South Pacific Service Ribbon with two battle stars and two Presidential Unit Citations, as well as Britain’s George Medal.

What had possessed Nash to not only volunteer for such perilous duty, but also remain behind enemy lines for more than two years?

What had possessed Nash to not only volunteer for such perilous duty, but also remain behind enemy lines for more than two years? In 1974 author Walter Lord interviewed the Coloradan for Lonely Vigil, his history of the Coastwatchers. Nash told Lord he’d joined the Australian force for the adventure. But Nash was no war lover. Every assignment he undertook, every letter he wrote home, expressed the motives of a young man whose primary objective was to contribute to a speedy end to World War II. Not content to remain in a safe berth stateside, he badgered superiors to transfer him to a hot spot. When activities there proved too tame, he sought transfer into another nation’s army in order to place himself where he could accomplish the most good. And there he stayed. As rescued airman Scott noted, the Coloradan Coastwatcher “just couldn’t leave ’til he saw the finish of it.”

Nash’s deep-seated sense of service to his country stands in contrast with his disdain for those he considered “draft dodgers.” In late 1943, while playing his dangerous game of hide-and-seek with the Japanese, Nash heard over the radio that a group of American coal miners had gone on strike, an action he viewed as a hindrance to the war effort. “I hope to see the whole lot in hell,” he wrote to his parents. “I hate their guts and all the rest of the big husky ones hiding behind their essential jobs.”

On his return home Nash again took up breeding registered Herefords. In June 1947 he married Clara Giem of Cañon City, Colo., with whom and where he remained until his death at age 87 on Aug. 1, 2005. The couple had seven children and lived to see 11 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. An advocate of education and the arts, Nash sold off much of his ranchland to sponsor scholarships at the University of Oklahoma and New Mexico’s Doel Reed Center for the Arts. For six decades he hardly spoke about the war, sharing his experiences only on rare occasions. “When Walter Lord came to the ranch to interview Dad,” daughter Harriet recalls, “we were all shooed out of the room; and when Dad walked out to take some air, there were tears running down his face. It was the only time I ever saw my father cry.” MH

Ron Soodalter is a frequent contributor to Military History and other publications and the author of Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader. For further reading he recommends The Coastwatchers, by Eric A. Feldt; Coast Watching in WWII: Operations Against the Japanese on the Solomon Islands, 1941–43, by A.B. Feuer; and Lonely Vigil: Coastwatchers of the Solomons, by Walter Lord.