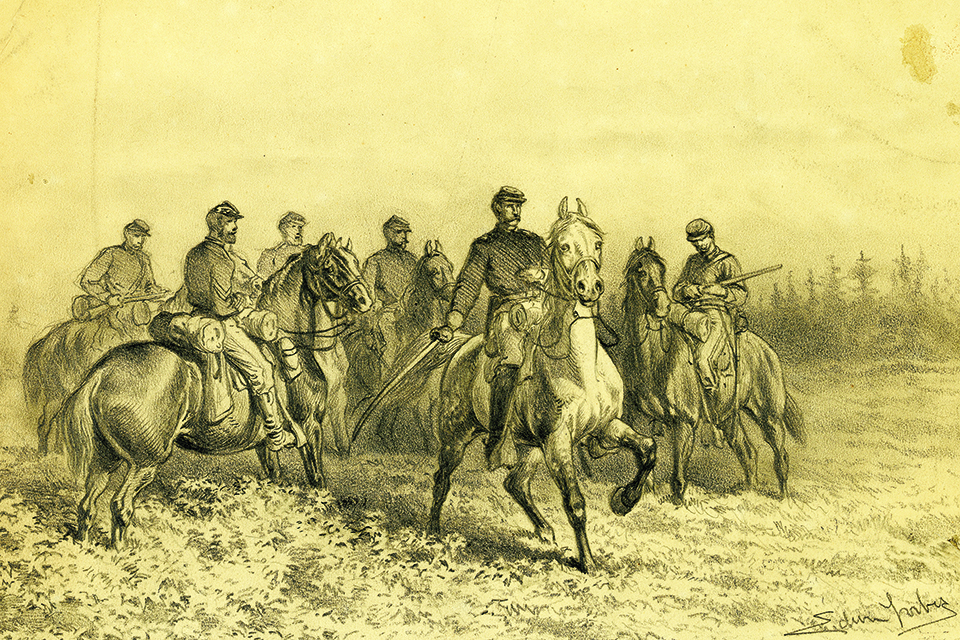

Union Sgt. George W. Quimby donned a Confederate uniform to gather intelligence during the March to the Sea

[divider_flat]IN THE FINAL EIGHT MONTHS of the Civil War, Union soldier George W. Quimby rode through the countryside of Georgia as well as North and South Carolina, spying and scouting in advance of Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee. Sherman’s scouts, often dressed as Confederate soldiers, regularly reported back on what they had discovered. Before he died in 1926, at the age of 84, Quimby penned a memoir of his experiences throughout the war that was never published. That manuscript was recently discovered by Stephen Murphy, the husband of one of his descendants, and Quimby’s recollections of his time as a pathfinder for Sherman are now available in The Perfect Scout: A Soldier’s Memoir of the Great March to the Sea and the Campaign of the Carolinas.

[divider_flat]Murphy, who is married to Quimby’s great-great-granddaughter, and historian Anne Sarah Rubin share editor credentials on this riveting account, which offers valuable insights into those final, intense months of intelligence operations during one of the most decisive campaigns of the war.

Quimby had spent 1862 through 1864 with the 32nd Wisconsin Infantry, and, after being captured by Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s men, was briefly a prisoner of war. Quimby eventually escaped and rejoined his unit, fighting in the Meridian Campaign in Mississippi, which served as a training ground of sorts for Sherman’s eventual operations in Georgia and the Carolinas. It was after the Union capture of Atlanta in September 1864 that Sgt. Quimby began his role as scout.

In The Perfect Scout, Quimby tells his story with considerable humor and wit, as well as a healthy sense of irony. Although he remained steadfast in his devotion to the Union long after the war, even after marrying a Southern woman, Quimby does not reflect ideologically on the war and reveals few insights into his motivations for serving, other than duty and honor.

Born in Ohio and raised in the Midwest, Quimby clearly had empathy for the yeoman farmers and poor Southern whites he encountered, but he was less sympathetic to the plight of the South’s enslaved men, women, and children. Despite occasionally praising those slaves who aided his mission, Quimby for the most part treated them with cruel indifference—an attitude unfortunately shared by much of the Army of the Tennessee, including “Uncle Billy” Sherman himself.

The Perfect Scout provides a unique lens through which to study two of the war’s most important campaigns. Following are some of Quimby’s revelations about the people he fought with and against, as well as how the war affected the South.

Quimby’s definition of a good scout

In describing the qualifications necessary of a good scout, I can only say that one should be quick to think, quick to act, and have a general knowledge of the geography and inhabitants of the country in which he operates, and withal he should have gentlemanly instincts. While he should be a strict partisan, he should also be possessed of a large amount of human kindness, and not be blind to the wants, acts, likes, and dislikes of the enemy’s home people. He should be familiar with their provincial dialect, if they have any, and have a thorough knowledge of their sympathies and hates.

With all these necessary qualifications, he would still be useless as a scout if he did not possess the required amount of moral courage to enable him to fly to the rescue of a friend or comrade if there be a “greater probability of saving their life than that of losing his own.”

How Scouts Operated

Quimby and his fellow scouts, most of whom had served in Midwestern regiments earlier in the war, reported to Captain William Duncan of Company K, 15th Illinois Cavalry, in Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s Right Wing of Sherman’s army. As Quimby explains:

Each of these scouts received from the secret service fund, in addition to their regular pay, $150.00 per month. They were selected on the recommendation of their Regimental and Brigade Commanders and were to serve during good behavior. They were expected to, and did, provide their own arms and horses, but were furnished with ammunition, forage, and rations.

We were allowed a good four-mule wagon to carry our baggage and camp outfit. This was under charge of a corporal who was wagon master, quartermaster, and generalissimo who had charge of all our camp and marching paraphernalia, and dour servants when we were absent on a scout. Each of us had a special contraband [runaway slave] whose duty it was to care for our horses and to lead our extra horse in the column when on the march….

We generally used a fresh horse each day, starting usually at three o’clock in the morning so as to get beyond the foragers before they got far advanced. We scarcely ever returned to the same camp at night, because the columns were nearly every day on the march, so we would be notified each morning as to the probable camping place the following night, which would be from twelve to twenty miles from the preceding. We scarcely ever went directly to the front of the column, leaving that for the advance guard, but went oblique to the army to the right or left, and sometimes away to the rear, as required by the general commanding.

The ethics of foraging

We had made a rule among ourselves never to do any foraging (except in the matter of horses, and [Confederate Gen. Joseph] Wheeler’s men did that also), and never to ask for anything without offering pay for the same. We had a double reason for this rule. First, we were liable to be captured at any time, and if, after foraging, we should be captured near the scene of our so-called depredations, it would be very apt to go hard with us. Put yourself in their place, and then judge.

Secondly, perhaps no other branch of service enabled one to see the inside of secession and to become fairly well-acquainted with the true feelings and general kindness of the individuals of the South, especially of the families and the old men and returned wounded soldiers. We gradually learned to respect, and then to sympathize with, them and finally would as soon thought of robbing our mother as those kind people of Georgia.

On his disguise as a Confederate

Some of my readers may wonder how it was that we, being dressed in Rebel uniform, could pass so readily at any time, day or night, to or from any point without being interrupted or arrested. I will state that nearly all of the Army of the Tennessee soon came to know one or more of us; besides each of the scouts carried a pass which read as follows…

Guards, pickets, patrols, and advance guards, pass the bearer ______, a special Scout at these Headquarters, at all times, for thirty days….

This pass would be renewed every thirty days, but later it was found not necessary to carry them and some of the boys got a little ‘squeamish’ about the possibility of being captured with such a pass in their pocket; therefore, they were eventually discontinued, except on special occasions. Of course, we were sometimes detained at an outpost where we were not recognized. In such cases it was only necessary for us to ask to be taken to some headquarters nearby where we could be identified.

Quimby on “the terrible atrocities of the invaders”

Next morning we divided our forces into three or four squads and advanced on different roads toward the column of troops. About noon [Sgt. Myron] Amick and I (who traveled together) arrived at a house where two foragers had been and had appropriated some ham and chickens, but had passed on to the next plantation. A young lady stood on the porch and recognizing us as Confederates came running out to tell us of the terrible doings of the Yankees….We consoled her as much as we could and expressed a wish that we had been there to get a chance at those Yankees, etc., etc. She invited us to stay for dinner, an invitation we were fishing for, and we accepted readily. The conversation on her part during the dinner was about the “terrible atrocities of the invaders.” She seemed worried because the two Yankees had gone on toward her “Grandpa’s.” While she was bidding us adieu, she looked up the road and saw the foragers returning, one of them mounted on an old grey mare, and exclaimed, “There they come now and they have got Grandma’s old Dolly, kill them.” The foragers advanced toward us unconcernedly, apparently thinking we were Federals, but because of our grey clothes had no reason for thinking. The horse and men were so loaded down with hams, chickens, and turkeys that they could not very well handle their guns. They came up to the gate where Amick and the young lady stood. Amick pulled a gun and demanded their surrender, which they did without word of protest. While he kept them covered, I stepped forward and relieved them of their arms, when the lady said, “Now, why don’t you kill them?” We told her that we had special orders to take such men when captured to headquarters, together with their plunder to be used as evidence against them, where they would be tried and shot.

This seemed to satisfy her and we started off with our “prisoners….” When we got out of sight of the plantation and told them the truth, returning their guns….This was the first time I had heard a lady use such cruel and murderous language. I firmly believe that if we had given her a gun, she would have killed them both.

The scouts’ insights into “Uncle Billy’s” plans…

The scouts often had occasion to cross lines of troops, and while few know our names, many knew who we were and our occupation. For some reason the soldiers had got it in their heads that the scouts were omnipresent and omniscient. Whenever we came in contact with our troops who recognized us, they would fire questions at us in such profusion that we were glad to get away. The burden of their queries was “Where are we going?” Even line officers were not averse to asking us, confidentially, where the terminus of the great march was to be, as though they thought we were in a better position to know than they, when, as a matter of fact, it is doubtful if twenty men in the entire army knew. The principal conversation in the ranks was speculation as to our final destination and purpose. Some would have it that we were simply trying to decoy Hood away from Nashville; others that we were keeping up the appearance of aiming for Augusta to call off the Confederate troops from points farther south, that we then would swing around and make a dash for Mobile. Still others insisted that we were marching “On to Richmond” to relieve General Grant from his dilemma.

Whatever the destination might be, all seemed to be confident of their ability to accomplish whatever “Uncle Billy” might plan.

The burning of Columbia, S.C.

When we arrived in the city, we found that it was full of cotton. Every warehouse and cotton shed was full, and cotton was piled up in backyards; many bales were in the streets and on abandoned carts.

We found a beautiful city, the residence streets being lined with many shade trees and ornamental fences.

In those days cotton was not baled with iron ties, as now, and during the war jute bagging could not be obtained; consequently bales of cotton were tied with wooden hoops or ropes. It seems that many negroes had, after the departure of Confederate forces from the city and before our arrival, cut the hoops or ropes of many hundreds, perhaps thousands of the abandoned bales, in various parts of the city. When it was released from these bonds, the cotton expanded to great dimensions and the extremely high winds of that day and night carried it like so much drifting snow, till it looked like a heavy drifting snowstorm had fallen. Every conceivable object that was capable of catching and holding a lock of cotton had done so.

I found quarters that night at the residence of an old gentleman, who had invited me to remain as a guest. It seemed that many of the citizens preferred a Yankee as his guest as he was sort of protection against marauders.

There had been some fires during the day, but all in comparatively safe places. General Howard had caused them to be extinguished as far as possible. About dark the city was as quiet as was Memphis at its most quiet time during the war.

Sometime between nine and ten o’clock that night, I was aroused from a sound sleep by the cry of fire and had scarcely time to dress myself when the house I was in caught fire. On reaching the street, I saw that the city was doomed. The wind had increased to nearly fifty miles an hour. When the fire first started, I doubt if there was a hundred soldiers in the town, aside from those on guard, but within twenty minutes it was full of soldiers, who came from nearby camps, some from curiosity and others possibly for plunder.

At first, Generals Howard, Sherman, and [Maj. Gen. John] Logan tried to stop the fire, but that being found impossible, they turned their attention to controlling the soldiers. The soldiers appeared to become frantic. It was known that large quantities of tobacco had been stored here for the Confederate government, and as tobacco had become a scarce luxury in our army, every effort was made by them to secure a supply. I, myself, saw Generals Sherman, Howard, Logan, and others try to turn this mass of soldiers back to their camp without success, until a regiment was brought in under arms who arrested all who did not escape.

I was told the next morning that this regiment had twenty-two hundred soldiers under guard, all of whom were later released.

Destruction in Georgia and the Carolinas

During the March to the Sea, all buildings of a public nature, such as cotton gins, corn mills, factories of every sort, fences and bridges, as well as railroads and telegraphs, were destroyed by order of division and corps commanders. There were probably a few private houses also burned by foragers through wantonness. This last was strictly against orders and would have been severely punished if the perpetrators had been caught in the act.

On the Carolinas Campaign, things were entirely different. While all buildings of public utility were destroyed, nearly half of the private buildings were also set on fire, not by order of anyone in authority, but by soldiers and refugee negroes. While this also was against orders, there seemed to be no effort being made to stop it.

It was reported throughout the army that General Logan had issued a special order to the 15th Corps, “Positively prohibiting under penalty of death, the setting on fire any fence or building when an ordnance train was passing.”

I presume that this was a false report, but at any rate it caused a general laugh whenever repeated.

Who was most responsible for the war

There were, no doubt, hundreds and perhaps thousands, of innocent families who suffered by these unnecessary and wanton acts. It was extremely probable that only a small minority of the people of that unfortunate state were really responsible for the deluging of the land with a bloody war. I have since become quite well acquainted with many people of South Carolina and found them to be…good citizens…. South Carolina was to the South what Massachusetts was to the North, that is, they did the talking and wanted others to do the acting. It was a common remark by the soldiers of all armies…especially those of the West, that those two states ought to be compelled to fight it out.

Susannah J. Ural is a professor of history and co-director of the Dale Center for the Study of War & Society at the University of Southern Mississippi.

_____

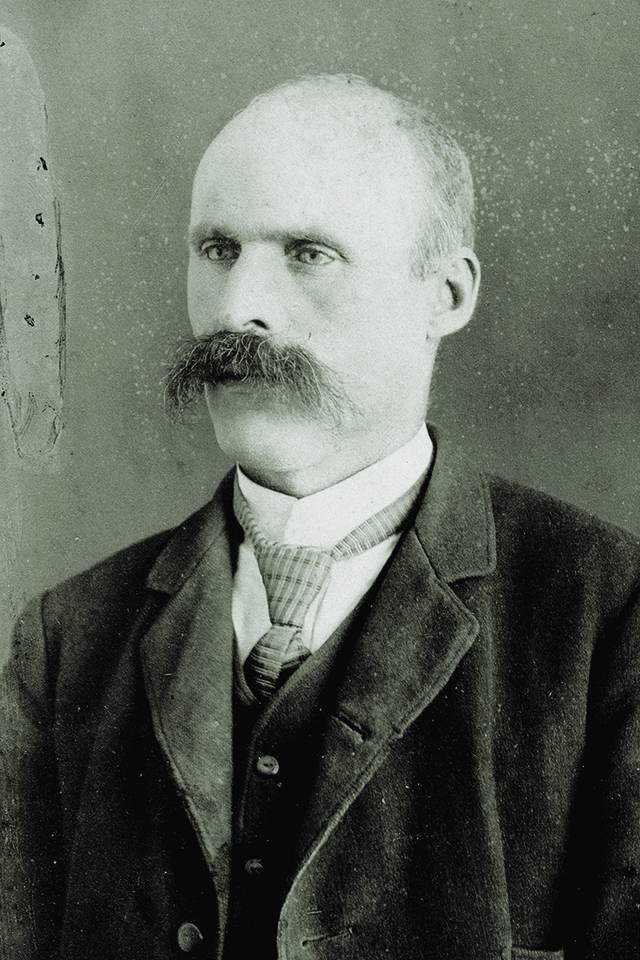

Scout Leader From Scotland

Like many Civil War soldiers, William Duncan, the commander of George Quimby’s scouting pack, was an emigrant. Duncan came to the United States from Scotland in 1856, settling in Illinois. After the bombardment on Fort Sumter, Duncan told Lucy Harwood, who he would eventually marry, “I need to fight for my country, my whole country.”

Duncan initially enlisted in the 36th Illinois Infantry, but he spent most of his service with the 15th Illinois Cavalry. By the time of the March to the Sea, he was a captain and highly respected as a scout. Perhaps his most daring exploit occurred when Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s men arrived outside of Savannah. Duncan, with Quimby and another scout, floated in an unstable dugout canoe down the Ogeechee River. Helped by area slaves, they slipped past the guns of Confederate Fort McAllister to reach the Union fleet offshore, informing it of Sherman’s proximity and to open up communications with the warships (See “Men With Deadly Rifles Outclass Fort’s Monster Cannons.”) Duncan also delivered a dispatch meant for Washingon, D.C., that explained Sherman’s success. The daring scout served in postwar Dakota Territory politics. He died on February 4, 1925, the same date as his wife.–D.B.S.