It’s a story of love (or possible abduction) and betrayal, set against the backdrop of an epic and sprawling 10-year siege.

First chronicled in the Iliad by the famous Greek poet Homer; written about by Herodotus the “Father of History”; and more recently, retold in the Warner Brothers 2004 blockbuster film, Troy, in which viewers watched Brad Pitt, playing a brooding Achilles, make exactly one facial expression throughout the entirety of the movie. For over 3,000 years the legend of the Trojan War has been recited and passed down.

Historians, archeologists, and civilians alike have been fascinated with the decade-long war waged between the Greeks and the Trojans. But the question remains, did it actually occur?

The British Museum seeks to answer this and “tread the line between myth and reality” in their latest exhibit Troy: Myth and Reality.

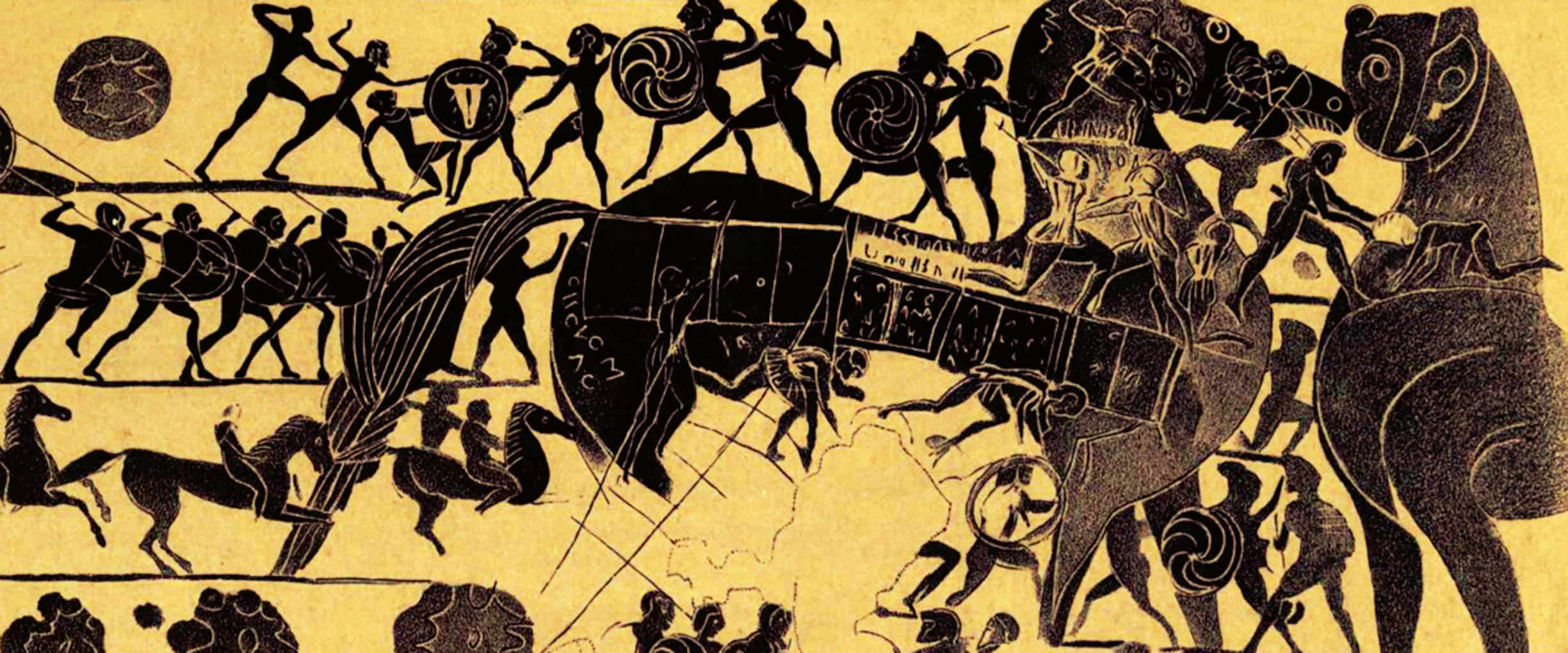

The war itself began after Paris, the prince of Troy, fled the city of Sparta with its beautiful queen, Helen. Some call it love. Others call it abduction. Either way, the cuckold King Menelaus, along with his brother, Agamemnon, assembled a large Greek army to attack the city of Troy. Helen’s face famously “launched a thousand ships” and condemned both city-states to 10 years of grueling warfare, ultimately culminating in the cunning Greek use of the Trojan Horse, and the destruction of Troy.

The ancient struggle is imbued with Greek mythology and falsities, and modern scholars, up until the 19th century, debated whether the city of Troy existed, let alone a war of that magnitude even took place.

The ruins of the city were discovered in 1870 by the wealthy Prussian businessman, Heinrich Schliemann. And although his methods and qualifications are now brought into question, Schliemann found signs that Troy had existed. The city was real.

Among the ruins archeologists have found evidence of fire and arrowheads that, according to author and historian Daisy Dunn, “hint at warfare.” Also surviving are inscriptions made by the ancient people of Hittites, who describe some dispute over ‘Wilusa’ – or Troy as they knew it. Many of these artifacts now reside within the British Museum.

And whether fanciful or fact, the story has continued to enthrall audiences. The museum’s exhibit, on display until March 8, 2020, entreats its patrons to examine the “fascinating archaeological evidence that proves there was a real Troy,” and to look at the “tantalising hints at the truth behind the mythical stories.”

“Regardless of how connected it is to fact,” writes Dunn, “The Trojan War myth had a lasting impact on the Greeks and on us. Whether it was inspired by a war waged long ago, or was simply an ingenious invention, it left its mark on the world, and remains as such of monumental historic importance.”