Current Kent State University students are often struck by the similarities they share with the students of the 1960s and ’70s. They can still grab a drink at J.B.’s or hear a destined-to-be famous band, like the James Gang or Devo, play at the Kent Stage. They can attend rallies for the biggest names in politics, from senators to presidential candidates, feverishly working to win the youth vote. And, of course, they can join a cause. Perhaps here the similarities are most striking. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s lives on in Black Lives Matter. The Women’s Movement echoes in the voices of #MeToo. The fight for equality, the environment and Native American rights—just to name a few—are still alive and well.

Yet, there are some very big differences that line the 50-year divide between the students of 1970 and 2020. Today, unlike 1970, most college students can vote. In 1971, the 26th Amendment to the Constitution lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, giving young people far more power to register their frustration with government officials, policies and organizations.

Although the United States is still sending troops to war, today the combat feels distant. The draft ended with the Vietnam War. Young people do not have to sit in front of a television, desperately hoping for a high number or considering their options should they face a tough choice. Some may not even understand what it means to register with the Selective Service System. Furthermore, very few students know what it is like to lose a friend or family member on the battlefield. The 58,180 daffodils, each representing a fallen U.S. soldier, that bloom during the annual commemoration of the May 4 shootings are a stark reminder of the magnitude of the brave lives lost in the Vietnam War.

May 4, 1970, is often called the “Day the War Came Home.” Fifty years later, it is important to remember that young people, whether soldiers in battle or battling for a cause, are often the tip of the spear of major societal change. It is also important to remember all that has been learned and lost in these fights.

A History of Activism

One of the myths surrounding the events of May 4, 1970, is that Kent State was a sleepy place where nothing ever happened. While Kent State was not as politically active as the University of California, Berkeley, or Columbia University in New York, the Golden Flashes do share a legacy of activism. In 1960, African American students organized a sit-in at what is now the Loft bar to demand service. A year later, some of those same students organized a picket line to protest the fact that only one landlord in all of Kent would rent to black students. In the summer of 1961, Danny Thompson, a white student from Cleveland who would later become the first poet laureate for Cuyahoga County, left Kent to join the Freedom Riders, black and white civil rights activists who rode integrated buses into Southern states to challenge segregation practices still in existence after the Supreme Court had declared them illegal.

In January 1965, inspired by the Free Speech Movement, a group of left-leaning students petitioned the administration to officially recognize the controversial Young Socialist Alliance as an official campus organization. At the same time, students in Kent, like students everywhere, challenged dress codes, fought curfews and, in big and small ways, bucked the status quo.

However, it was 1968, “The Year that Rocked the World,” as historian Mark Kurlansky called it, that truly shook up campus life. In one of the best examples of collective activism in Kent’s history, the Black United Students organization encouraged African American students to walk off campus to prevent university administrators from punishing protesters who had joined with Students for a Democratic Society to physically block the police department of Oakland, California, from recruiting on the campus after being invited by Kent’s law enforcement school. An advertisement in the Daily Kent Stater, on Nov. 5, 1968, sought men ages 21-29 who met the height, weight, vision and character standards for the Oakland jobs, which paid $10,000 a year.

“The Oakland police were in the national spotlight due to their violent interaction with African American residents of Oakland and more specifically, its volatile encounters with the Black Panther Party,” writes Lae’l Hughes-Watkins in “Between Two Worlds: A Look at the Impact of the Black Campus Movement on the Antiwar Era of 1968-1970 at Kent State University,” an article in the journal Ohio History. In a remarkable move of solidarity, on Nov. 19, 1968, more than 300 black students left their classes to walk off campus, deliberately passing through the Kent State arch that normally served as a welcome sign. Days later they returned to campus with a loud round of applause from administrators and students after President Robert White dropped all charges against the protesters for “lack of evidence.”

SDS members continued to press the university for change. In April 1969, they launched the Spring Offensive with four “non-negotiable” demands, the first of which was an unsuccessful attempt to prod the administration to disassociate itself from the ROTC on campus. As symbols of the military, ROTC facilities were targets of protest across the nation. Those demands, combined with the increasing militancy of some SDS members, placed the student organization and the university on a collision course. After a series of arrests and the occupation of a campus building—another common tactic of student radical groups—the SDS leaders were expelled from campus, and the organization’s charter was revoked. Persistent claims to the contrary, the SDS played no part in the events of May 4, 1970.

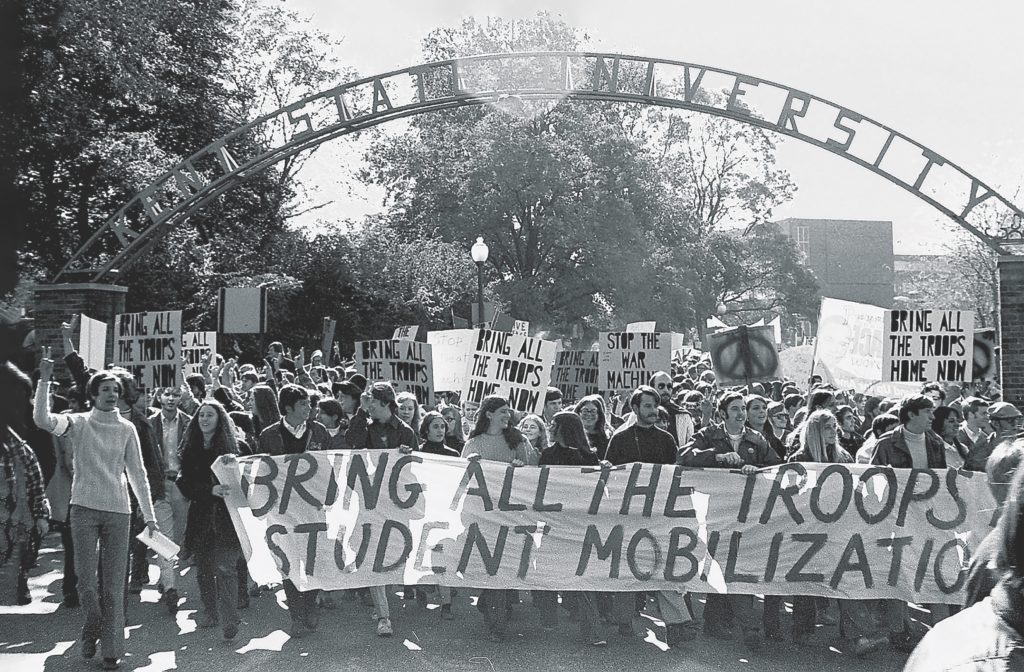

SDS was far from the only anti-war organization on campus. On Oct. 15, 1969, hundreds of Kent State students and their allies joined the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, a day of demonstrations at college campuses across the nation. At the front of a line carrying a sign that read “Bring All the Troops Home” stood Allison Krause, one of the four students killed by the Ohio National Guard just seven months later.

Nixon’s Cambodia Address

In many ways, the story of the Kent State shootings begins in Cambodia. On Thursday, April 30, 1970, at 9 p.m., President Richard Nixon went before a live television audience to announce what he called the Cambodian Incursion. North Vietnamese forces were violating Cambodia’s neutrality by using borderlands there as staging areas for “hit-and-run attacks on American and South Vietnamese forces,” he said.

With polls showing a growing number of Americans opposed to the war, Nixon chose his words carefully. “This is not an invasion of Cambodia,” he explained, “Once enemy forces are driven out of these sanctuaries, and once their military supplies are destroyed, we will withdraw.”

The announcement was met with near instant opposition, especially among young people. As Kent State sociology professor Jerry Lewis, an eyewitness to the shootings, noted in his Feb. 24, 2010, oral history with the Kent State University Library, Nixon’s speech “was important for two reasons, both negative. One, not only was the war not ending, but the more important…the war was spreading. And that really sent a signal to everybody to be quite upset over it.” That weekend there were at least 132 protests held on college campuses. Only one ended in tragedy.

Friday, May 1

Around noon the day after Nixon’s address, nearly 500 people gathered at Kent State’s Victory Bell, in the grassy Commons area at the center of the campus, to protest what they saw as a broken promise. The Cambodian Incursion, they believed, was an expansion of the war Nixon had promised to end. A group of history majors, some of them veterans, planned the event and operated under the name W.H.O.R.E, World Historians Opposed to Racism and Exploitation. After a series of speeches, they buried a copy of the Constitution ripped from a textbook. As the rally ended, the protesters called for a larger, more organized demonstration on Monday, May 4, at the same time and the same place.

The nice spring evening on Friday brought people from all walks of life to downtown Kent to grab a drink with friends, watch the basketball game and listen to some of the best local bands. However, the tensions of the afternoon spilled into the night. A trash fire was lit in the street, someone threw a beer bottle at a police cruiser, and protesters accosted cars as they drove by.

Concerned, Mayor LeRoy Satrom declared a civil emergency in Kent at 12:20 a.m. and closed all the bars. As bar patrons returned to their cars or stumbled back to their dorms, some in the crowd threw rocks at windows and painted anti-war slogans on downtown businesses. Fearful that things could get out of hand, the mayor called the governor’s office, and the Ohio National Guard was put on notice. The Guard was in nearby Akron, where Teamsters were striking and troops had been deployed to protect nonunion truckers from attacks.

Saturday, May 2

The morning dawned quietly. As students sobered up from their drinking the night before, some went downtown to help with the cleanup. With rumors that there could be more protests, and possibly more vandalism, in town and on the campus, Satrom instituted an 8 p.m. curfew for the town. Around 5 p.m., he officially put the National Guard on alert. Soon the Guard left Akron and headed to Kent. Causing some confusion, university administrators issued a curfew of 1 a.m.—much later than the curfew set for town.

Around 7:30 p.m., about 600 students gathered around the Victory Bell shouting anti-war and anti-ROTC slogans. They started to march around campus, calling into the dorms to get others to join the protest. The crowd had swelled to 1,000 to 2,000 students by the time the protesters reached the ROTC building just after 8 p.m. Students tried to burn down the building with railway flares, at least one gas-soaked rag and some lighters.

When Kent city firefighters arrived, demonstrators tried to cut their hoses and otherwise disrupt them. The harassment forced the firefighters to leave, and the Kent State University Police arrived, using tear gas to disperse the crowd. Shortly after 10 p.m., the fire department returned, this time escorted by the National Guard, which had just arrived in town. By the time the guardsmen reached the ROTC building, it was in flames.

There is no question that Kent State students attempted to burn down the ROTC building and blocked the efforts of the firefighters working to put out the blaze, but there is a controversy about what happened after the students dispersed. Some eyewitnesses claimed that the fire was under control when they were forced to leave.

As the authors of This We Know: A Chronology of the Shooting at Kent State, May 1970, published in 2013, write, “Although it is widely assumed that the building was burned by demonstrators, it has been suggested by some researchers that the arson was the work of agents provocateurs.” Some eyewitnesses and researchers believe that the authorities were either neglectful in putting out the fire or that someone restarted the blaze after the students left in order to justify further action against them.

Sunday, May 3

Nothing about Gov. James Rhodes’ stance was unclear. Running for a U.S. Senate seat in a tight Republican primary race to be decided on May 5, Rhodes used the actions of Saturday night as a chance to bolster his position as the law-and-order candidate (an unsuccessful one, as Tuesday’s primary results would show). After touring the smoldering remains of the ROTC building, Rhodes returned to the fire station to deliver a fiery address, declaring, “We are going to eradicate the problem—we’re not going to treat the symptoms.” He compared the students behind the damage to “brown shirts,” or Nazis, and the “nightriders,” another name for the Ku Klux Klan.

That evening, as they had done all weekend, students gathered at the Victory Bell. Upset about the war, alarmed by the governor’s words and frustrated by the 850 guardsmen occupying their campus, they asked to speak to White, the university president. The National Guard used tear gas to split apart the crowd, and about 200 students ended up at the corner of Lincoln and Main streets for a peaceful sit-in. In front of the arch that had served as the backdrop to the BUS walkout in 1968, they again asked to talk to White. Again, the president did not meet with them.

The students wanted the Guard removed from campus and the end of the curfew. Some students tried to negotiate with the Guard on behalf of the protesters. Believing an agreement had been reached, they started to disperse. As the students left, they were told the university curfew had been moved from 1 a.m. to 11 p.m. Some of them, not taking the sudden news well, hurled rocks and obscenities at the guardsmen, who responded with tear gas as they chased the demonstrators into campus buildings. Two individuals later claimed that they were injured by the bayonets of guardsmen.

Monday, May 4

Kent was, and still is, a “suitcase” school. A large proportion of the 20,000-strong student body goes home for the weekend. Those students returned on Monday to a campus they barely recognized. Helicopters had buzzed in the sky all night, and students walking to class that morning encountered guardsmen monitoring their movements. Even for those who planned to attend classes like normal, it was an unusual day.

The official investigations into the May 4 shootings clearly show that communication was a problem. While the mayor had declared a civil emergency for the city just after midnight on Saturday, May 2, the paperwork for a state of emergency was never filed. Additionally, there is little consensus on what was decided at a key 10 a.m. meeting between the Guard’s commanding officer, Brig. Gen. Robert Canterbury, White, Satrom and other local officials, including the police chief.

The biggest misunderstanding centered on the noon rally. Canterbury later testified that White told him it was banned. White claimed otherwise. The university president was off campus eating lunch with fellow administrators at the nearby Brown Derby steakhouse during the rally, and Canterbury proceeded under his impression that the ban was in place. Before cellphones and social media, official pronouncements traveled slowly on campus. Few students received the university-distributed leaflets incorrectly informing them that a state of emergency had been declared and the National Guard was now in control of campus.

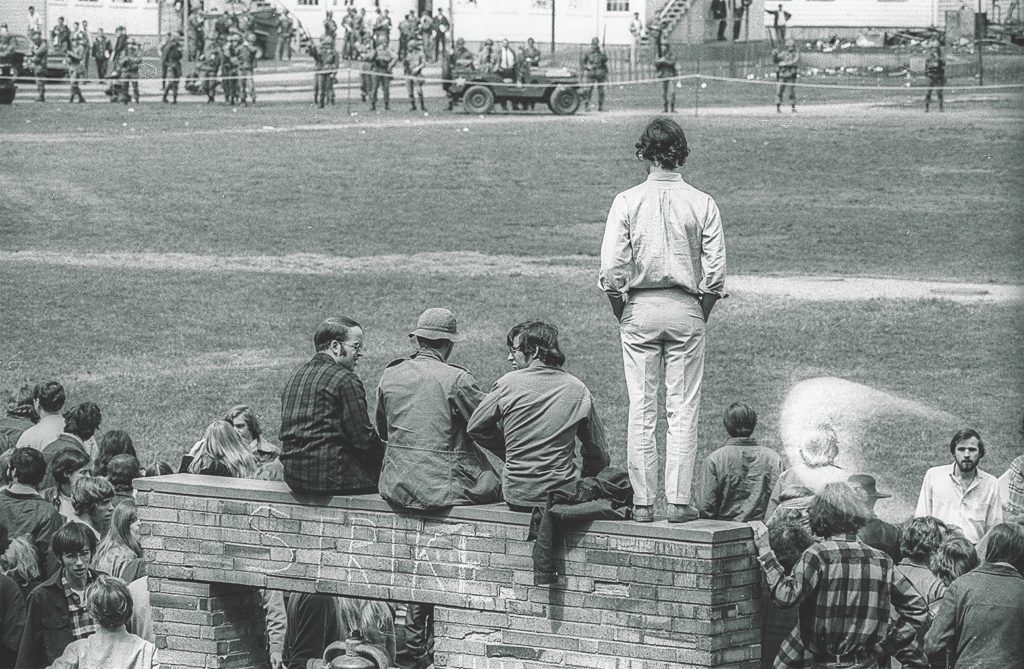

Students started to gather at the Victory Bell around 11:30 a.m. for the noon rally. After the events of the weekend, the arriving protesters were expressing their anger about more than the Cambodian action. But some students showed up just to check out the scene. Morning classes were letting out. Students and faculty could grab lunch at the Student Union, next door to the remains of the ROTC building. Estimates of the number of people who attended the rally range from 1,500 to 2,000.

Just before noon, Canterbury ordered the crowd to disperse. Between the ringing of the Victory Bell and the chants from the protesters, it is unlikely many people heard the general. A KSU police officer grabbed a bullhorn to better relay the order. Still the crowd, largely massed about 500 feet across the Commons, did not budge. The KSU officer flanked by two members of the Guard approached the gathering in a jeep. The students chanted, and some flipped the bird in the direction of the guardsmen or threw rocks. After two more confrontations, Canterbury ordered his men to fire tear gas at the demonstrators. It was a windy day and the gas quickly dispersed, allowing some students to throw the tear gas canisters back at the Guard.

About 12:05 p.m., Canterbury ordered the 113 troops guarding the ROTC building to advance on the crowd and disperse students gathered on the other side of the Commons at Blanket Hill, the highest point in the area and the site of Taylor Hall. Marching toward the protesters was a line of three Ohio National Guard units: Company A, 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry Regiment, on the right flank; Troop G, 2nd Squadron, 107th Armored Cavalry Regiment, in the center; and Company C, 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, on the left.

The soldiers, wearing gas masks and moving shoulder-to-shoulder, split into two groups after they left the ROTC rubble and crossed the Commons. One group, Company C, went to the left, toward the Taylor Hall-Prentice Hall parking lot, stopped at a position in the open space between Taylor and Prentice Halls and stayed there. Company C was not involved in the shootings.

The other group, Company A and Troop G, went to the right toward a concrete sculpture of a pagoda, at the top of Blanket Hill next to Taylor Hall. Canterbury followed closely behind. Company A and Troop G crested the hill. By then many of the demonstrators had retreated to the parking lot and a football practice field next to it. The guardsmen maneuvered down to the football field. Students in the area shouted curses and threw rocks.

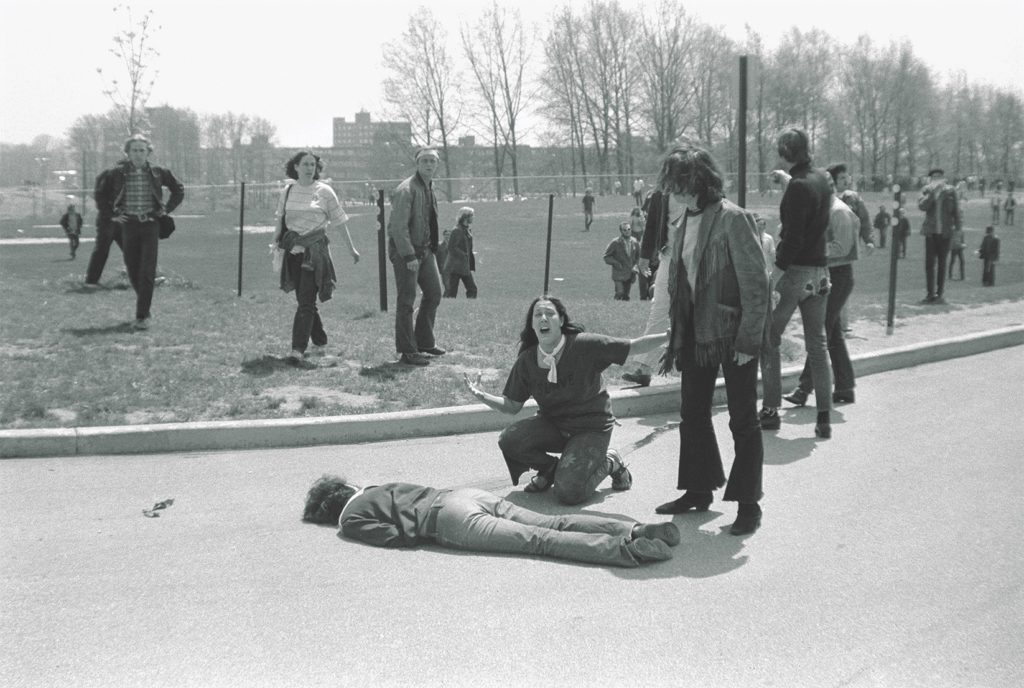

It was in the football field that the guardsmen first aimed (but did not fire) their weapons at students, including Jeffrey Miller, who would, however, be shot dead just minutes later—an event that became one of the day’s iconic images in a Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph by student John Paul Filo showing 14-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio, a runaway from Miami, kneeling over Miller’s body.

After about 10 minutes at the practice field, Company A and Troop G turned and moved back toward the Pagoda, a student art project that became a historic landmark after May 4. Many guardsmen thought they were returning to their original position at the ROTC building.

Some groups of students parted to let the troops pass, and those at the top of Blanket Hill walked down the other side. But other students continued throwing rocks at the withdrawing guardsmen, and some guardsmen threw rocks back at them.

Then at 12:24 p.m., as the troops approached the Pagoda, they turned and 28 of the 76 guardsmen fired 67 shots over the course of 13 seconds, killing four and wounding nine. Most of the shooting guardsmen fired into the air, but others shot directly into the crowd. Investigators determined that no rocks were being thrown at the time of the shooting.

There remains much debate over whether or not there was an order to fire. The eyewitness testimony, both from civilians and the National Guard, provides no clear consensus. Even among witnesses who claim to have heard an order, their description of the command varies widely.

More recently, this debate has centered on the analysis of what is called the Strubbe tape, named after Terry Strubbe, a student who recorded the rally and shooting with a tape recorder perched on his dorm window. In 2010, forensic audio experts Stuart Allen and Tom Owen announced that with further enhancement and evaluation they found evidence of the words, “Guard!” followed several seconds later with the command, “All right, prepare to fire!” While some believe the study, skeptics remain.

After months of investigation, Nixon’s Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, released Sept. 26, 1970, determined that the “actions of some students were violent and criminal and those of some others were dangerous, reckless, and irresponsible,” but the investigators ultimately concluded, “The indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable.” Furthermore, the report stated, “The Kent State tragedy must mark the last time that, as a matter of course, loaded rifles are issued to guardsmen confronting student demonstrators.”

Mindy Farmer, Ph.D., is a public historian and the director of the May 4 Visitors Center at Kent State University.