Acoustic shadows bedeviled commanders on both sides during the war.

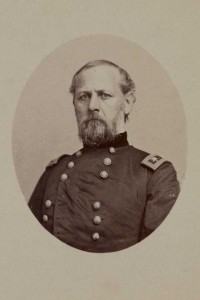

“I received with astonishment the intelligence of the severe fighting that commenced at 2 o’clock. Not a musket shot had been heard nor did the sound of artillery indicate anything like a battle.” So said Union Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell when he appeared before a military commission investigating his conduct during the October 8, 1862, Battle of Perryville. Buell had to admit sheepishly that for hours during the battle he had been deaf to the fighting, the victim of an atmospheric anomaly known as an “acoustic shadow.” He was not alone. During the war, several engagements would be influenced by the inability of critical military personnel to hear the sounds of battle involving their troops.

In his defense, Buell contended that his inability to hear the sound of battle “was probably caused by the configuration of the ground which broke the sound, and by the heavy wind, which it appears blew from the right to the left during the day.” This explanation, unbeknownst to him, was scientifically correct. According to Charles Ross, a physics professor at Longwood College in Virginia and the recognized expert on Civil War acoustic shadows, the zone of silence that hung over the Perryville area “was temperature-induced refraction, combined with the effects of terrain.” The weather had been hot for weeks, and heated air near the ground pushed the sounds of battle upward. That, combined with the rugged terrain surrounding the battlefield, buffered the sound waves that might have otherwise alerted Buell to the battle taking place less than three miles from his Dorsey Farm headquarters. Also, the wind direction kept the smoke and sounds of the fighting from wafting over the grove where he was enjoying a leisurely afternoon lunch.

Major General Charles C. Gilbert, commander of the army’s III Corps, was also dining with Buell. After the war, he corroborated Buell’s testimony. “Owing to the conformation of the ground and to the limited use of artillery on both sides, no sound of the battle had been heard at General Buell’s headquarters…” Lieutenant Colonel J. Montgomery Wright, assistant adjutant general serving as a courier for Buell, also heard nothing until he stumbled upon Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook’s I Corps at about 5 p.m. By then, McCook’s beleaguered men had been fully engaged with most of the Confederate army for nearly three hours. After the war, Wright reported that “up to this time I had heard no sound of battle; I had heard no artillery in front of me, and no heavy infantry firing.”

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]erryville was the largest battle fought in Kentucky and one of the war’s fiercest. Union casualties exceeded 4,200 killed, wounded, and missing. Confederate losses are estimated at nearly 3,400. Most historians consider the battle a Pyrrhic victory for the Confederates. After learning that only a fraction of Buell’s army had been engaged in the fighting that first day, General Braxton Bragg chose to withdraw from the field rather than resume the fight the next day. The best chance for the Confederacy to control the strategic state of Kentucky probably had been lost.

Eight months earlier, an acoustic shadow had almost derailed the career of budding star Ulysses S. Grant. Fortunately for Federal fortunes, General Grant overcame the shroud of silence that kept him from hearing the Confederate attack launched against his troops during the February 1862 Siege of Fort Donelson in Tennessee.

Fort Donelson was the key to opening the Cumberland River to Union naval traffic. But from February 6, when Union Commodore Andrew Foote’s flotilla swarmed up the Tennessee River and conquered Fort Henry, and the opening of Grant’s siege on nearby Donelson, the weather changed from spring-like warmth to arctic cold. Sporadic skirmishing on February 13-14 proved inconclusive. Then the temperature dropped, the wind began to blow, the ground froze, and the underbrush-choked ravines around the fort thickened with layers of snow and ice. Brigadier General Lew Wallace, bringing a corps off river transports to join Grant’s besiegers, later noted: “The wind whisked suddenly around to the north and struck both armies with a storm of mixed rain, snow, and sleet.” Conditions became ripe for poor acoustics.

While the storm howled, a council of war convinced Confederate commander Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd to break the siege by attacking the Union’s right wing on the morning of the 15th. At 2 a.m., 10,000 men began moving from their rifle pits for a dawn attack. Opposing Floyd’s line was Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand’s inexperienced 1st Division, which reportedly heard no enemy movement. After the war, Wallace wrote: “It seems incomprehensible that columns mixed of all arms…could have engaged in simultaneous movement, and not have been heard by some listener outside.” That incomprehensible silence was broken at first light when the woods beyond the Union pickets roared to life with a man-made storm of artillery and small-arms fire. Wallace characterized the sound “as if a million men were beating empty barrels with iron hammers.”

While his beleaguered soldiers fought for their lives, Grant was also on the move, though he was heading away from the fighting. As the Confederates began to redeploy, Grant received a request from Commodore Foote asking for a morning meeting. Since Foote had been injured the day before, Grant felt obligated to meet his comrade on the Union flagship St. Louis, anchored five miles downstream. At dawn, Grant mounted his horse and began a slow journey down a badly rutted, frozen road along the river.

Could Grant have been oblivious to the sounds of battle exploding just a few miles away? Lieutenant Colonel Manning F. Force, bringing the 20th Ohio Infantry up the same road, maintains that he could have. Following the war, Force remembered that “there was nothing in the sound that came through several miles of intervening forest to indicate anything more than McClernand’s previous assaults.” Grant expected no offensive movement from the fort’s defenders and had left orders that no attack be made while he was away. So, if he heard anything, he probably attributed it to more long-range pot-shots fired by skirmishers.

Grant emerged from his conference with Foote at about noon. By then, the battle had raged for nearly four hours. Just as he stepped on dry land, one of his aides, Captain William S. Hillyer, galloped up with the startling news. Together, the two men raced up the river road, arriving on the battlefield about 1 p.m. By that time, the initial Confederate advance had been stemmed, thanks largely to the initiative shown by Wallace who, without orders, moved some of his command to support the reeling McClernand. But Grant, unlike Buell at Perryville, quickly assessed the situation, issued clear and decisive orders, and prepared to retake the ground he had lost. By the end of the day, Union forces reoccupied the earthworks they had held in the morning and a disheartened Confederate high command pondered both escape and surrender.

The next morning, Grant issued his famous “unconditional surrender” demand. His prewar friend, Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, prepared to hand over the fort and about 12,000 of its defenders. Floyd and fellow brigadier Gideon Pillow had slinked off during the night and a bellicose gray cavalry colonel, Nathan Bedford Forrest, defiantly led about 500 troopers along a frozen creek bed to safety. Grant’s steadfast determination and calm decision making in the face of unexpected conditions, both natural and man-made, contrasted markedly with Buell’s obliviousness, indecision, and fault-finding. Grant became an overnight hero, yet acoustic shadows continued to dog his trail and would affect his command decisions at another battle seven months later.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]coustic shadows played a prominent role throughout the war. At Iuka, Miss., in September 1862, the phenomenon disrupted a planned attack by Grant and Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, resulting in a stalemate. A loss would have seriously threatened Confederate prospects in northern Mississippi.

On August 10, 1861, an acoustic shadow cost Confederates at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in Missouri, forcing Generals Benjamin McCulloch and Sterling Price to react quickly to defeat Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon’s Federals. And during the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston ran afoul of an acoustic shadow at Seven Pines on May 31, 1862, a battle that cost him his command and almost his life. In that clash, Johnston did not learn of the fighting until about 4 p.m. General Robert E. Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis had just arrived at Johnston’s headquarters and were dumbfounded to find the general still waiting for news.

The historian for the Army of the Potomac’s XI Corps noted that at Chancellorsville, Va., on May 2, 1863, “the sounds of the distant conflict were not heard, or were too confused and indistinct to awaken suspicion. The noise of the battle did not seem to extend far.” Major General Daniel Sickles, III Corps commander, “did not hear a sound of the fight which wrecked the Eleventh Corps,” allowing Stonewall Jackson’s men to complete their epic Flank March by rolling through Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s unsuspecting corps from the flank and rear. Historian Stephen Sears has noted that Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, commanding the Army of the Potomac, never heard the sound of Jackson’s attack even though he was only a few miles away. “By some fluke of acoustics,” Sears writes, “the roar of Jackson’s assault did not immediately reach Federal headquarters at the Chancellor house.” In the judgment of physicist Ross, “the poor acoustics associated with the Battle of Chancellorsville must have been due to the thick foliage in the region.”

On the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum, commander of the Union XII Corps, claimed that atmospheric conditions and topographic features prevented him from hearing sounds of the fighting occurring only a few miles away. As such, his decision to take a lunch break at Two Taverns delayed him in coming to the aid of the beleaguered I Corps and might have undone what could have been a convincing Union victory on the first day. It did earn the earnest general the sobriquet of “Slow Come” that dogged him for the rest of his career.

At the critical Battle of Five Forks, Va., on April 1, 1865, Confederate commanders George Pickett and William “Rooney” Lee were enjoying the hospitality of Maj. Gen. Thomas Rosser at a “shad bake” only a few miles from the battlefield. They never heard Union Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s troops overrunning their leaderless soldiers until it was too late to affect the course of the battle. The Union victory finally broke the Siege of Petersburg and led to the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia eight days later.

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ince the Civil War, battlefield communications have, no surprise, improved vastly. But weather, in all its forms, and varying terrain continue to influence the ability of soldiers on the ground to implement even the best-laid strategy and execute the tactical maneuvers designed to achieve victory on the field of battle—just as the phenomenon of acoustic shadows had bedeviled commanders on both sides during the Civil War.

What Causes Acoustic Shadows?

Acoustic shadows occur when a particular combination of air temperature, wind speed, wind direction, and terrain prevent certain sounds from reaching listeners even only a short distance away. Sound moves away from its source in waves, like ripples on a pond. Basically, three things can make it change direction, an effect known as refraction. At ground level, the two most common causes of sound waves traveling in unexpected ways are wind direction and sound absorption. A person downwind from the sound source can hear it better than someone upwind. Therefore, wind blowing away from listeners will make it harder for them to hear the sound than if it were blowing toward them. Obstacles between the source and listeners also absorb sound; obstacles on the ground like undulating terrain, dense trees and leaves, and buildings, and obstacles in the air like dense fog or heavy snow. The same atmospheric anomalies can also amplify the sounds at locations far from

their source.

Reading Civil War after-action reports shows how important sound was to a commander directing his troops. Battlefields were usually too large for a commander to scan in their entirety. The sounds of fighting, therefore, helped determine where to deploy troops or send reinforcements. At times, attacking troops were told to move only when they heard the firing from other,

possibly unseen, attackers. But what if a commander unknowingly found himself in a seemingly preternatural zone of silence? Clearly, his command and control ability would be significantly compromised and that’s exactly what happened to the hapless Buell at Perryville.

Gordon Berg, a retired civil servant, is a regular contributor to America’s Civil War.