Though more than 1,800 people in Nuremberg, Germany, died in a fiery hailstorm amid one million incendiary bombs and 120 blockbusters dropped on the city by the British Royal Air Force on Jan. 2, 1945, a horde of Nazi-accumulated artwork survived undamaged in a bunker hidden about 78 feet underground. The secret art bunker of Nuremberg, today known as the Historischer Kunstbunker, held the keys to the historic relics of the Nazis’ Party Rally city.

The Nazis used a medieval tunnel system underneath Nuremberg’s imperial castle to hide the city’s ancient treasures, including the Imperial regalia of the Holy Roman Emperor, valuable paintings and even pieces of stained glass windows from local cathedrals. The underground maze had existed since the 14th century—medieval workers used hammers and chisels to carve a labyrinth of tunnels and vaults underneath the castle hill. The naturally cool chambers had been used to store beer and vats of pickled cabbage. The tunnel system runs about four stories deep and spans an estimated total area of six acres—equating to a space of more than six football fields.

By the time war broke out in 1939, Nazi officials had already developed a detailed plan to preserve “cultural treasures” in Nuremberg held sacred by Hitler’s Third Reich. These items included works of art, religious items and artifacts made in Nuremberg, the former seat of the Holy Roman Empire. Described since the 19th century as the “Treasury of the German Empire,” Nuremberg was home to such notable artists as Albrecht Dürer, Hans Sachs and Augustin Hirschvogel. The Nazis found propaganda value in Nuremberg’s history and transformed it into a symbol of the Third Reich during the 1930s. City officials collaborated with Heinrich Himmler and the SS to hide artwork in the bunker. The storage site was designed by Dr. Konrad Fries, head of the city’s Air Raid Protection department, an architect named Dr. Heinz Schmeissner, and Julius Linke, head of the city’s monument preservation department.

The secret tunnel system was completely renovated within six months after the war began. Previously, the tunnels were used to store Nazi Party Rally equipment, including props, lighting, and allegedly a podium used by Hitler. Renovations transformed the tunnels into a state-of-the-art artifact preservation facility with air conditioning, ventilation and moisture-control systems, and modern plumbing. Shock-resistant steel doors were designed to withstand bomb tremors. Guards kept watch in chambers equipped with bunks. The facility contained a wireless communication hub and an escape route with a ladder to the surface. Six main chambers were used to store artwork.

Artwork with cultural significance to the Third Reich was systematically removed during the war from Nuremberg and other German cities—and from conquered territories—and stored in the bunker. The horde of items packed into the subterranean maze included historic armor and weapons, a globe created by Martin Behaim in 1492, scientific instruments, manuscripts, statues, paintings and drawings. The Nazis removed stained glass windows from Nuremberg’s Frauenkirche and St. Lorenz cathedrals and packed them in carefully constructed wooden crates. Afterwards they installed substitute glass in the windows and draped them with long flags to conceal the missing panes from view. Fountains and altarpieces were also stored in the bunker. Artwork was packed into padded boxes as protection from bomb blasts.

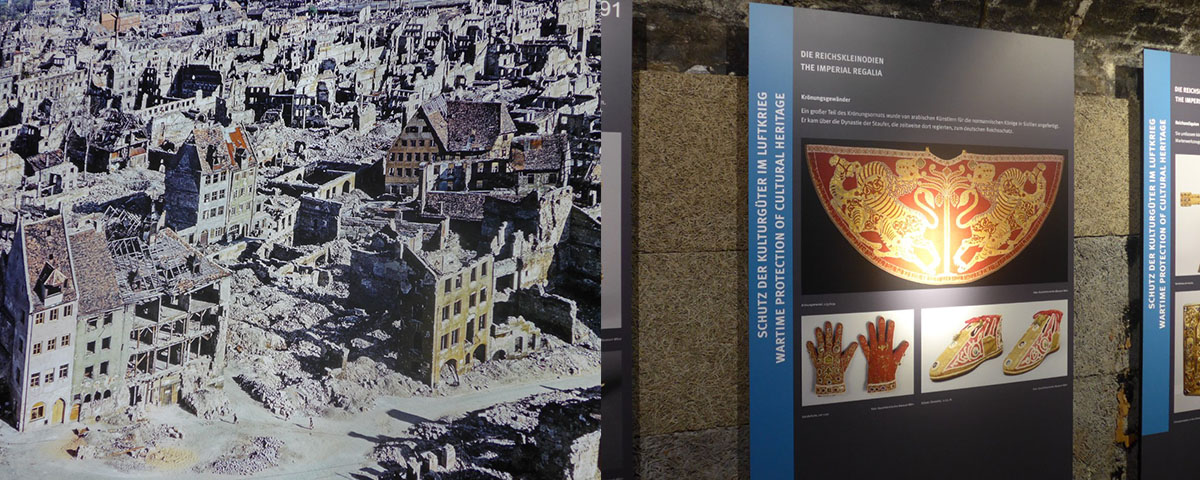

The most famous items stored in the bunker were the Imperial treasures, called the “Reichskleinodien,” which included the jeweled crown, scepter and orb of the ancient Holy Roman Emperor. The Nazis removed these objects from Austria in 1938. Another high-profile item was a Marian altar created by famed German artisan Veit Stoss, stolen from Krakow cathedral in Poland. According to postwar interviews conducted by the U.S. Army, various Nazi leaders worked together to confiscate and store the items, with Himmler and the S.S. playing a key role. Himmler ordered that the Imperial treasures be kept in copper containers.

Operations at the bunker were kept top secret. Allied bombings in January and February 1945 razed the Nazis’ hallowed city to rubble, killing several thousand people and leaving more than 100,000 residents homeless. All artwork in the bunker was totally unscathed. More than 20,000 civilians huddled in a makeshift air raid shelter beneath the city’s Paniersplatz Square during Allied attacks, unaware of the art bunker’s existence. As Allied troops closed in at the end of March, Nazi officials frantically relocated the Imperial treasures due to fear of looting.

As houses were leveled, streets blocked with rubble and city residents starved, Nazi extremists launched a crackdown to prevent surrender—and nearly destroyed the art bunker. Fanatical Nazi politician Karl Holz commanded Nuremberg’s defenses. He ordered that anyone caught attempting to flee the city, waving a white flag or failing to report for work duties would be executed. Using city loudspeakers to spread terror, Holz declared: “Who does not want to live with honor must die in shame,” and referred to the Allies as “devils.” On Holz’s orders, four Nuremberg residents were publicly executed for “disgrace” and an additional 35 citizens were sent to Dachau concentration camp for alleged defeatism. Holz planned to drastically enforce Hitler’s “Nero” decree (Nerobefehl), which called upon Germans to self-destruct rather than surrender. As American troops closed in on the outskirts of Nuremberg, Holz prepared to deploy demolition teams to blow up whole sections of the city—including the art bunker, according to later testimony by city official Albert Dreykorn.

Holz’s plan to destroy the art bunker was allegedly the last straw for city mayor Willy Liebel, a close associate of Albert Speer. Liebel had deported Jews and helped implement Nuremberg racist laws, yet switched side when confronted with the possible destruction of German artwork in the bunker. As American troops entered the eastern outskirts of the city on April 20, 1945, Liebel took refuge in a shelter below city police headquarters and attempted to contact the U.S. Army to negotiate surrender. Hearing of this, Holz entered the room and shot the mayor in the head, according to eyewitness Dreykorn. Claiming Liebel “committed suicide,” Holz ordered troops in the city to hold to the last man. The resulting siege cost many lives on both sides during fierce house-to-house fighting. Ultimately Holz was killed during a standoff with American soldiers after refusing four chances to surrender. Following a victory celebration on the city’s main square, American troops moved into Nuremberg castle and discovered the steel doors of the secret art bunker.

The U.S. Army launched an investigation under the leadership of German-born U.S. Intelligence officer and “Monuments Man” Lt. Walter William Horn. An art expert, Horn had attended Heidelberg University and emigrated to the U.S. due to opposition to Nazism. Horn interrogated 21 people in Nuremberg, including two city councilors. After conducting hard rounds of cross-examination, Horn learned the location of the hidden Imperial treasures. Nazi officials confessed to hiding the items behind a wall in the Paniersplatz civilian air raid shelter, 80 feet below ground. According to Horn’s investigation, the Nazis planned to use the Imperial treasures as symbols to inspire a future resistance movement.

All works of art and cultural items stored in the secret art bunker of Nuremberg were eventually returned to the places they had occupied before the war. Due to bomb damage, it took more than 70 years before various historic objects could be displayed in restored buildings in Nuremberg. Despite protests from city residents—including Dr. Ernst Gunter Troche, director of the Germanic National Museum—the Holy Roman emperor’s Imperial treasures were returned to Vienna, where they had been for 134 years before the Nazis claimed them.

Access to Nuremberg’s historic Art Bunker (Historischer Kunstbunker) is available only through guided tours, which are offered several times daily. For detailed visitor information: www.felsengaenge-nuernberg.de