Frank Sinatra had been headlining at New York’s Copacabana since the end of March 1950 when he took to the nightclub’s stage late on April 26 for that Wednesday evening’s last set. Only about 70 customers, less than 10 percent of the Copa’s capacity, were still in attendance. Around 2 a.m., Sinatra opened his mouth to sing—and nothing came out. “Just dust,” he said later. His audience stared. He stared back. Bandleader Skitch Henderson thought Sinatra was fooling around. “But then he caught my eye,” Henderson recalled. “I guess the color drained out of my face as I saw the panic in his.” Finally, the singer whispered “Good night” and walked offstage, where he began coughing up blood. His vocal chords had hemorrhaged. Doctors told Sinatra not to talk for at least a week. He canceled a booking in Chicago.

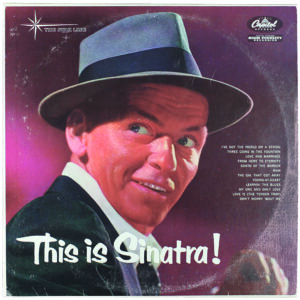

Sinatra’s career had already been in a nosedive. Now he entered a wilderness period that saw him forced to produce musical drivel, until Capitol Records took a chance on him. The label paired the singer with arranger Nelson Riddle, a collaboration that revitalized Sinatra’s studio work. Embraced in Riddle’s artful, sophisticated orchestrations, Sinatra reinvented himself for adults—as an exuberant swinger on upbeat albums or a broken-hearted brooder on introspective outings. His collaborations with Nelson Riddle were the mold that reshaped Frank Sinatra into the cultural icon familiar today.

Sinatra had been on top of the world. The Hoboken, New Jersey, native knew from boyhood that he wanted to be a singer. He was working as a singing waiter at the Rustic Cabin, a roadhouse in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, when trumpeter and bandleader Harry James came in one evening to size up the local talent. James hired Sinatra in February 1939, paying his protégé $75 a week.

Soon Sinatra was aiming higher—at the country’s top band, led by trombonist Tommy Dorsey. In January 1940 Sinatra left James, who voluntarily tore up his singer’s contract, to sign a three-year deal with Dorsey for $125 a week. Sinatra learned a lot watching the trombonist work. “He would take a musical phrase and play it all the way through seemingly without breathing for 8, 10, maybe 16 bars,” Sinatra told Life magazine in 1965. “Why couldn’t a singer do that, too?” Sinatra also listened to violinist Jascha Heifetz, noting how Heifetz maintained a melody line without taking a break. “It was my idea to make my voice work in the same way as a trombone or a violin—not sounding like them, but ‘playing’ the voice like those instruments.”

Sinatra studied microphone technique, using amplification to bond with his listeners as singers before him like Rudy Vallee, Russ Columbo, and especially Bing Crosby, had. “He played the mic with a virtuosity that influenced every singer to follow,” wrote Crosby biographer Gary Giddins. “It was his ultimate ally, perfectly suited to his way with dynamics and nuance and timbre.” Amplification meant singers no longer needed to belt to reach the balcony. Now they were able to whisper, sigh, and confess. Sinatra could sound like he was singing directly to the listener, a connection intensified by his smooth, soothing baritone. Delivering ballads, he came across as romantic, tender, and vulnerable.

In 1941, after Billboard named Sinatra America’s top vocalist, he began angling to get out of his three-year contract with Dorsey, in part because Columbia Records executive Emanuel “Manie” Sacks was offering a deal. Unlike James, however, Dorsey wanted a large payout. The negotiations left both men bitter. “I hope you fall on your ass,” Dorsey told Sinatra.

Nelson Smock Riddle joined the Dorsey band as a trombonist in 1944. Born on June 21, 1921, in Oradell, New Jersey, he was the only child of a dominating French mother and a sign-painter father. Interested in music, the youth learned to read music and play trombone and started performing and arranging—creating the musical framework for songs—with regional bands.

Riddle’s first important mentor, Bill Finnegan, had been arranging for Glenn Miller since the late 1930s. In weekly lessons, Finnegan taught young Riddle how to experiment with combinations of instruments to arrive at a unique sound for each song he arranged. Finnegan endorsed classical music “as the prime source for musical richness.”

When Miller’s demands on Finnegan’s time led the older man to quit teaching, Riddle freelanced as an arranger until bandleader Charlie Spivak hired him full time. “He was a nice guy, very humble,” Spivak saxophonist Don Raffell said of Riddle. “It seemed as though he felt intimidated at all times. His mother was the cause. She practically told him what time to go to the bathroom.” During World War II, Riddle served in the Merchant Marine, playing in and arranging for that service’s orchestra until he graduated to Dorsey’s band, joining on May 11, 1944, in Chicago. “Tommy was pleasant to me in his own particular gruff way and quite supportive of my budding career as an arranger,” Riddle said. “He was, and always will be, one of my heroes.”

Riddle profited from his exposure to Dorsey’s arrangers, citing Eddie Sauter, Hug Winterhatler, and Freddie Norman as influences.

Drafted in April 1945, Riddle spent an uneventful 14 months in the Army, returning to New York to freelance as an arranger until singer and radio show host Bob Crosby lured him to California to handle that role for Crosby’s program. That partnership didn’t last, but Riddle found work writing music for NBC radio. He also studied with Italian-born composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, whose lessons on symphonic arranging had a huge impact. Riddle broke through in 1950 when he arranged “Mona Lisa” for Nat King Cole. That huge hit made Riddle a mainstay at Cole’s label, Capitol Records.

While Riddle was apprenticing, Sinatra was rising to dizzying heights. Something about the skinny young man with the oversize bow ties, the aching voice, and those blue eyes set young women called “bobby-soxers” ablaze. Louis B. Mayer at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer signed Sinatra to a seven-year acting contract—“one of the sweetest deals in movie history,” said James Kaplan in a 2010 biography. At Columbia, Sinatra established his first great musical partnership, with arranger/conductor and fellow Dorsey alum Axel Stordahl. Bald and tweedy, the pipe-smoking, professorial Stordahl wrapped Sinatra in almost classical arrangements. Biographer John Rockwell described the resulting recordings as “a wash of strings and lush, neo-Tchaikovskian arrangements to accompany Sinatra’s gorgeous, lyrical, intimate, introspective ballad singing.” His work with Stordahl earned Sinatra the nickname “The Voice.”

Sinatramania peaked on October 11, 1944, with the “Columbus Day Riots.” New York’s Paramount Theater had booked the vocalist, whose appearance drew a horde of bobby-soxers, numbering perhaps 10,000, to queue up along Broadway and around the block. When the situation boiled over, the 150-some policemen on hand proved no match for teenage hormones. “Shop windows were smashed; people were hurt and carried off in ambulances,” wrote Bruce Bliven in The New Republic. “For Sinatra that stand at the Paramount was a kind of culmination, the final explosive orgy of his cult of youth,” wrote Kaplan. It seemed World War II was ending, and normal life was beckoning. Sinatra’s young followers were growing up.

After the war Sinatra succumbed to celebrity. If he wasn’t slugging reporters, he was squiring women not his wife, Nancy, around town. An affair with smoldering actress Ava Gardner ended his marriage. MGM canceled his movie contract. His left-leaning politics caught the FBI’s attention. Sinatra’s professional life was just as rocky. His record sales were in decline, his voice was showing signs of strain, and his movies were diminishing in quality and popularity. The crisis at the Copa was a physical manifestation of a career in free fall.

At Columbia, oboist-turned-producer Mitch Miller became chief of recording. Miller had a knack for producing gimmicky hits. However, except for Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra, a 331/3 rpm 10-inch with up-tempo arrangements by George Siravo that went nowhere commercially despite a degree of quality, Miller’s stewardship of Sinatra marked the nadir of the singer’s career. Miller’s touch was exemplified by “Mama Will Bark,” a duet with Swedish model Dagmar augmented by a man howling like a dog. Sinatra and Columbia parted ways in 1952.

At 37, Frank Sinatra had the hallmarks of a has-been—until he desperately but successfully lobbied Columbia Pictures boss Harry Cohn to cast him as the doomed GI Maggio in the adaptation of James Jones’s eve-of-World War II novel From Here to Eternity. The role would win Sinatra an Academy Award for best supporting actor. And then Capitol Records gambled on him.

Several people took credit for getting Sinatra to his new label. Capitol artist Jo Stafford said she touted the singer to producer Dave Dexter Jr., who went to hear him and was moved to give a favorable report. But Alan Livingston, Capitol vice president for artists and repertoire, said Sinatra’s agent had called him, trying to gauge Capitol’s interest. “Sinatra had hit bottom, and I mean bottom,” record company executive Livingston told author Charles L. Granata. “He couldn’t get a record contract, and he literally, at that point, could not get a booking in a nightclub. It was that bad—he was broke, and in a terrible state of mind.”

Livingston signed Sinatra anyway.

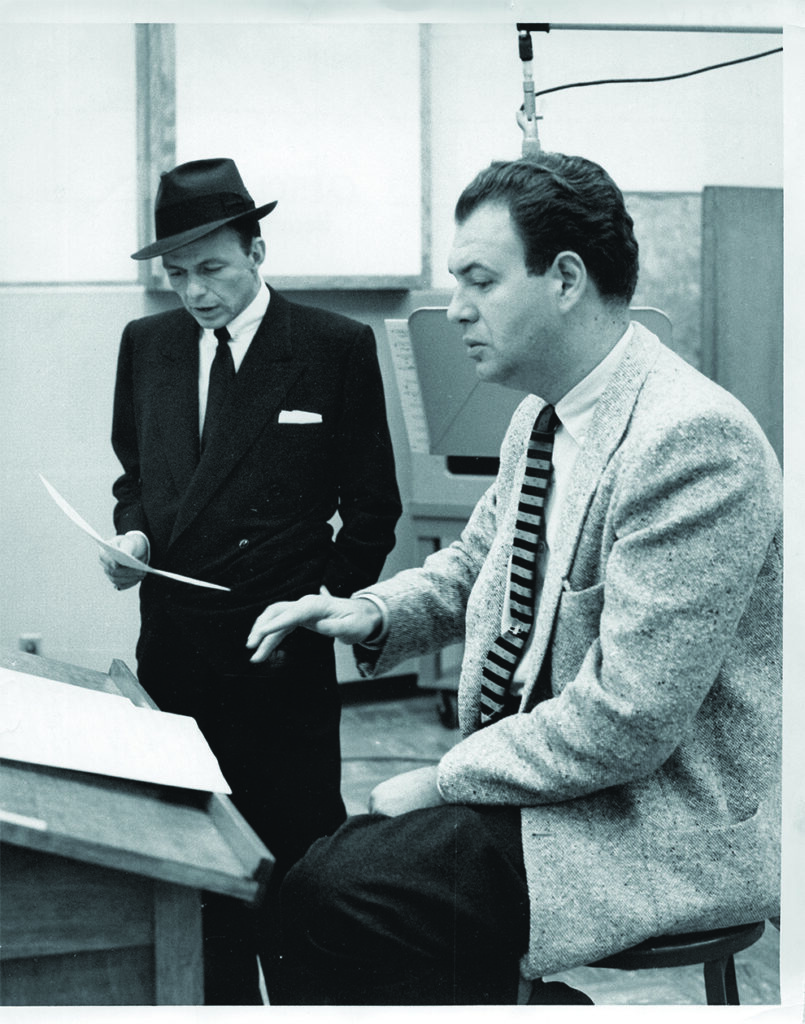

His first Capitol recording was a 45-rpm single, “Lean Baby” and ”I’m Walking Behind You,” arranged and conducted by Stordahl and recorded on April 2, 1953. Sinatra wanted to keep working with Stordahl; the label preferred to pair him with brash, playful bandleader Billy May. But the hard-drinking trumpeter, known for his group’s energetic brass and “slurping saxes,” was on tour, so Capitol enlisted Riddle. “We were all very high on Nelson, he was marvelous!” Alan Livingston said. “He knew how to back a singer, and make them sound great, and I wanted Frank to have the benefit of that.”

Livingston booked Riddle for a session with Sinatra on April 30. The men had crossed paths in 1944 when Sinatra hosted the Dorsey band on radio show All-Time Hit Parade, but Sinatra seems not to have made that connection.

“Frank came in, and saw a strange man on the podium, and said, ‘Who’s this?’” producer Alan Dell said. “I said, ‘He’s just conducting the band—we’ve got Billy May’s arrangements.’” Knowing Capitol’s preferences, Riddle even had made the session’s first two arrangements—“I Love You” and “South of the Border”—sound like May’s work; the label on the single “South of the Border” credits May. One chart was pure Riddle, however. “I’ve Got the World on a String,” with its brassy self-confidence, announced the arrival of a different Frank Sinatra. Yesterday’s tremulous, vulnerable crooner had become manly, upbeat, tough, exuberant. Sinatra listened to the tapes.

“Jesus Christ, I’m back,” he said. “I’m back, baby, I’m back!”

That session began a collaboration that continued, off and on, for more than three decades—according to Riddle biographer Peter J. Levinson, a total of 318 recordings, plus 25 television programs and the soundtracks to seven motion pictures.

“Sinatra and Riddle remained essential to each other because each man pushed the other to heights neither could achieve individually,” wrote music historian Will Friedwald. “And the Sinatra-Riddle sound has since become what we think of when we think of Sinatra; the pre-Riddle period can be reduced to a prelude; the post-Riddle era to an afterthought.”

At a glance, Sinatra and Riddle seemed similar: both were Jersey boys and only sons of dominating mothers. Both emerged from the Big Band era and duty with Tommy Dorsey. But there the equivalency ended. The singer was a hot-tempered boozer, a brawler who wore his nerves on his sleeve. The arranger was quiet and introspective, with a sardonic wit born of a grim childhood. Julie Andrews called him “Eeyore.” Biographer Peter J. Levinson summed up Riddle’s demeanor as “gloom and unhappiness.”

Recording with Sinatra, Riddle said, could be “tense and businesslike.” Work on an album started when the two met to discuss approaches to the songs Sinatra wanted to sing. He would start “with the most agonizingly specific comments on the first few tunes, often referring to classical compositions for examples of what he expected to hear in the orchestration,” Riddle recalled. But Sinatra was known for a short attention span when not actually recording and after giving a few detailed instructions he would drift into vagueness, finally telling Riddle to do what he felt was best. “My headache would start to subside, my pulse return to normal, and another Sinatra-Riddle album would be launched,” Riddle said.

Riddle listed a third key ingredient. “Music to me is sex,” he said. “It’s all tied up somehow, and the rhythm of sex is the heartbeat.” He thought his best material for Sinatra had “the tempo of the heartbeat.”

Sessions “were loaded with electricity,” Riddle wrote. Sinatra was an activist in the studio. Though he did not read music, he was a superlative musician who knew what he wanted to capture on disk and was quick to spot and question flaws. He might skip an arrangement and move on to the next number, but never in anger. “He’d never give out compliments, either,” said Riddle. “If he said nothing, I’d know he was pleased. He just isn’t built to give out compliments and I never expected them. He expects your best—just that.”

Sinatra did hand out a few compliments in a 1961 talk with Douglas-Home. “Nelson is the greatest arranger in the world,” he said. “A very clever musician, and I have the greatest respect for him. He’s like a tranquilizer—calm, slightly aloof. Nothing ever ruffles him. There’s a great depth somehow to the music he creates.”

The apex of the Sinatra/Riddle collaboration may be their second full LP, Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! Recorded over six days in January 1956 in Capitol Studio A at 5515 Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles, the album was done live—singer and musicians in the same studio. “Frank always preferred to be on stage with the band,” Capitol mixer John Palladino told Charles L. Granata. “He wanted eye contact with everyone, he charged the musicians—that’s what made his sessions so special.”

Songs opens with “You Make Me Feel So Young,” a jaunty introduction to the Capitol-era Sinatra. The first side ends on a more thoughtful note with “Love Is Here to Stay” by George and Ira Gershwin. The song, one of the LP’s more subdued numbers, opens with Sinatra’s long-time pianist Bill Miller, one of a platoon of musicians who recorded with the singer and Riddle over the years. Another was trumpeter Harry “Sweets” Edison, whose muted instrument always provides the perfect playful touch. A third was bass trombonist George Roberts, whose sound made a big impact on Riddle’s work and who later provided the ominous melody line in John Williams’s theme for Jaws.

Trombonist Milt Bernhart makes himself heard on the standout track, Cole Porter’s “I’ve Got You Under My Skin.” Sinatra added the chart at the last minute—to arrange it, Riddle pulled a late-nighter—and recorded it on January 12, 1956. After running through the number the first time the musicians gave him a spontaneous ovation. “Skin” became an instant classic, from the open’s bouncing baritone saxophones and bells to the bari saxes winding things down. Sinatra had told Riddle he wanted a “long crescendo” and the arranger obliged, emulating Ravel’s “Bolero” in a middle section that raises the musical temperature before Bernhart’s trombone solo heats the song to fever pitch. “I left the best stuff I played on the first five takes,” Bernhart told Charles Granata. The brass section microphone was suspended overhead. On take 10, Bernhart said, the engineers asked for more volume. Sinatra fetched a box for Bernhart to stand on, putting the bell of his horn nearer the mic. After the song’s instrumental break, Sinatra leans in for an emotional climax before he and the band bring the song softly back to earth. “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” is one of the undisputed highlights of the Sinatra/Riddle songbook.

Sinatra had many other musical peaks, often with Riddle. There were valleys, too, but never again did Sinatra stand at the brink of failure the way he had before signing with Capitol. Eventually his arrangement with Capitol chafed. He left the label in 1960 for Reprise Records, which he founded to escape corporate control. Once his own Capitol contract ended, Riddle arranged five albums for Sinatra at Reprise. Though not all in the same league as the Capitol albums, the Reprise sides boast artful Riddle arrangements, from the string-drenched symphonics of The Concert Sinatra (1963) to the jazz organ percolating through Strangers in the Night (1966)—and they have Sinatra’s mature voice, aged like vintage bourbon.

Sinatra used arrangers other than Riddle, including Billy May, Don Costa, Quincy Jones, and Gordon Jenkins. And Riddle kept busy, working with Ella Fitzgerald, Judy Garland, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Oscar Peterson, and many other artists, as well as scoring for movies and television and releasing recordings with the Nelson Riddle Orchestra.

The partnership foundered in 1978, when Sinatra abruptly canceled an appearance at a tribute for Riddle, a slight the arranger could not forgive. The two never recorded together again, although Sinatra hired Riddle as musical director for a Ronald Reagan inaugural concert in January 1985. Nelson Riddle died that October 6, not long after charting with albums of standards he arranged and conducted for pop singer Linda Ronstadt that capitalized on his Sinatra sound.

When Sinatra died in 1998, he was celebrated as a giant of American popular music, a status grounded by the musical foundation Nelson Riddle provided. “Nelson’s arrangements allowed Frank to swing like I’d never heard him swing,” drummer Greg Field told Riddle biographer Levinson. “That ‘I’ve Got the World on a String’ arrangement sounded as modern as anything we played. The beginning of the Frank Sinatra we all knew and loved—I think Nelson had a massive impact on that.”

This story appeared in the August 2020 issue of American History.