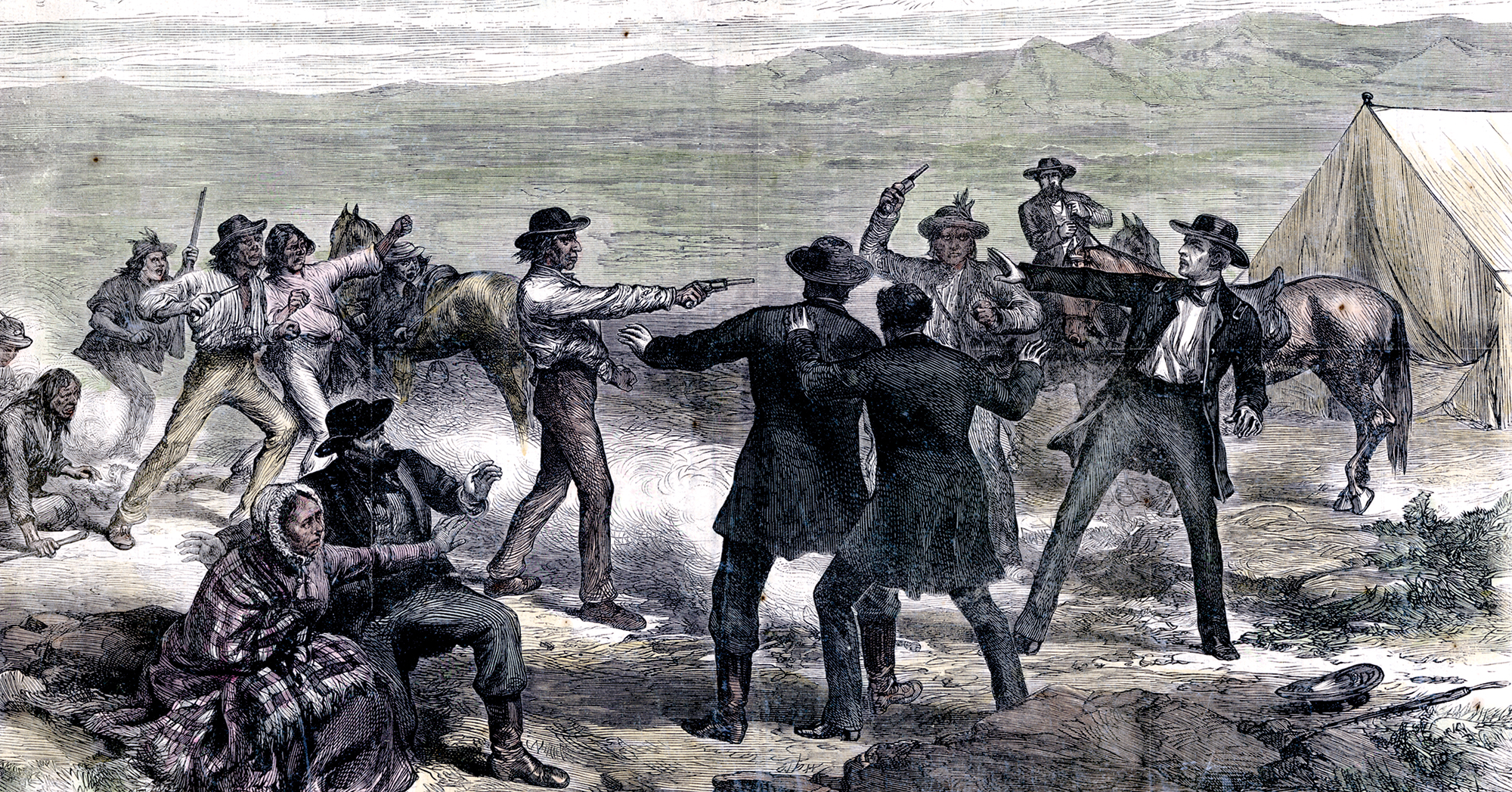

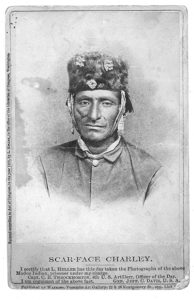

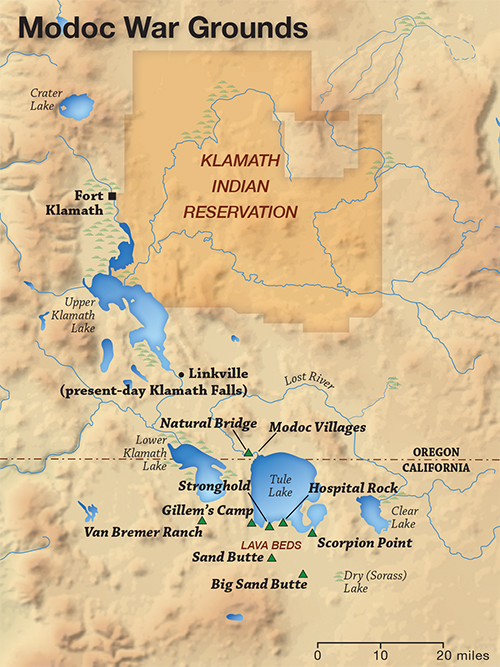

No sooner had the troopers of Company B, 1st U.S. Cavalry, dismounted in the off-reservation Modoc village on the west bank of southern Oregon’s Lost River at Natural Bridge than 2nd Lieutenant Frazier Boutelle drew his revolver and fixed his stare on a tribesman settlers had nicknamed Scarface Charley. The young Modoc, rifle at the ready, glared back from but a few yards away. At the same instant each made the move both knew was coming. Boutelle snapped up his revolver, Charley raised his rifle, both fired. Before the smoke cleared in the early morning light of Nov. 29, 1872, the Modoc War had broken out.

As Boutelle and Charley—both still standing and unhurt—realized death had passed them by, a firefight exploded. Three or four Modocs went down in the first volley, one dead. But the troopers, who stood in the open as the warriors dove for cover, took the worst of it. Eight dropped, one dying on the spot, another soon thereafter. Somehow Boutelle managed to rally his depleted unit, ordered a charge and pushed the Modoc men out into the brush beyond the village. The lieutenant then had his troopers evict the Modoc elders, women and children, destroy all abandoned weapons and set the vacant winter houses ablaze.

Fire and fury fell simultaneously on a smaller Modoc village on the east bank of the Lost River. A vigilante posse from Linkville (present-day Klamath Falls) that had followed the troopers south got the firefight for which they were gunning. In the exchange one vigilante shotgunned a 6-year-old child, then turned his weapon on a mother and infant. While the woman survived the blast, buckshot tore her baby in half.

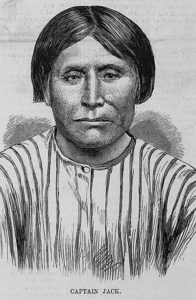

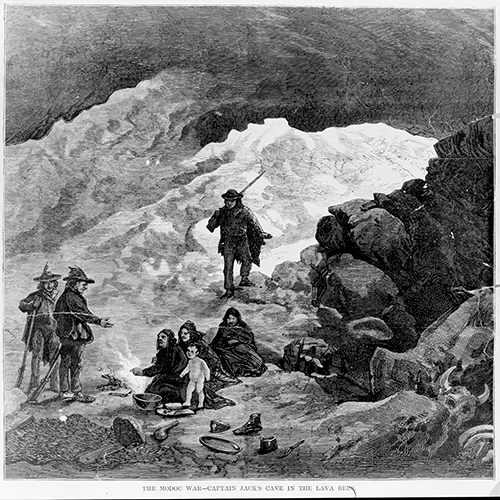

Most of the retreating Modocs gathered at the mouth of the Lost River on Tule Lake, piled into canoes and began the long paddle to the south shore, over the state line in California. Led by Kientpoos—known to settlers as Captain Jack—they were bound for the Stronghold, a plateau amid the Lava Beds on the southwest corner of the lake where for millennia threatened Modocs had taken refuge.

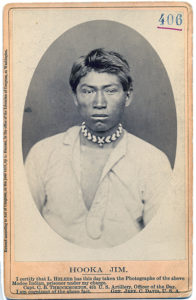

Even as the evacuees paddled south, Hooker Jim led eight other mounted Modocs from the eastern village down the lakeshore, bent on revenge for the shooting of the woman and children, an unforgivable violation of tribal rules of engagement. By the time they connected with those holed up in the Stronghold, the warriors had shot down a dozen or so settlers, all men and adolescent boys.

Despite its dramatic and bloody outbreak, however, the Modoc War initially appeared just one more police action against off-reservation Indians on the frontier. Soon, though, the conflict occupied center stage in the American consciousness. It vexed the Ulysses S. Grant administration for most of the next year, claimed the life of the only general killed in the Indian wars and became the only such conflict in which a newspaper reporter interviewed opposing Indian leaders amid the hostilities.

Such consequence was fitting. After all, the war had been brewing for decades. When it did break, a long-dammed hell flooded out.

Until 1846 the Modocs had had little contact with Anglo-Americans, save for the occasional fur trapper. That year a group of Oregonians led by Lindsay and Jesse Applegate mapped a wagon road from Fort Hall in what is now Idaho to the Willamette Valley. Following ancient Indian trade routes across northern Nevada, northeastern California and south-central Oregon, the Applegate Trail gave emigrants another way into Oregon besides the Columbia River’s perilous rapids.

Until 1846 the Modocs had had little contact with Anglo-Americans, save for the occasional fur trapper. That year a group of Oregonians led by Lindsay and Jesse Applegate mapped a wagon road from Fort Hall in what is now Idaho to the Willamette Valley. Following ancient Indian trade routes across northern Nevada, northeastern California and south-central Oregon, the Applegate Trail gave emigrants another way into Oregon besides the Columbia River’s perilous rapids.

At first the Modocs were little troubled by the transiting wagons and let them pass. But as the emigrant tide swelled, it left in its wake overgrazed meadows, decimated game and fouled water. Within a year an epidemic, most likely of measles, swept through the Modoc villages. Of a population numbering around 2,000 the disease claimed 150 lives. By 1849 the aggrieved Modocs were harrying incoming settlers.

The newly admitted state of California noticed. On Jan. 6, 1851, Peter Burnett, the first civilian governor, gave a state of the state address focused primarily on California’s “Indian problem.” A former Missouri slaveholder, Burnett believed that racial conflict between Anglo-Americans and Indians was inevitable. “A war of extermination will continue to be waged,” he declared, “until the Indian race becomes extinct.” Backing such a strategy without debate, the state Legislature soon floated the first of $1.5 million in bonds (some $47 million in present-day dollars) to fund local militias tasked with killing Indians.

‘A war of extermination will continue to be waged,’ California Governor Peter Burnett declared, ‘until the Indian race becomes extinct’

Two such militias, one led by Ben Wright, a Quaker turned Indian fighter, invaded Modoc country that summer and killed upward of 30 to as many as 90 tribe members. The next fall the Modocs attacked a 16-wagon train along Tule Lake, inflicting significant casualties on the party. Wright responded in kind, spearheading a larger militia that capped its campaign by slaughtering some 40 Modocs under a false flag of truce. And so it went. In 1854 an Oregon militia killed two dozen more Modocs. In 1856 a California militia claimed to have killed more than 185 Modocs, but in reality slew only one—a woman. Modocs were getting scarce.

Indeed, by 1864 the Modoc nation had declined to approximately 350 members. That year it joined the equally beleaguered Klamaths and Yahooskin band of Northern Paiutes in signing the Council Grove Treaty, ceding more than 6 million acres and agreeing to move onto the Klamath Indian Reservation in south-central Oregon.

Reservation life, though, proved harsh and humiliating. The U.S. Senate took five years to ratify the treaty, meanwhile withholding funds for food and shelter. Reduced to eating their horses, most of the Modocs abandoned the reservation for traditional village sites along the Lost River. That set the stage for the cavalry raid of Nov. 29, 1872. When that assault went sideways, it left the Modocs and the United States at war.

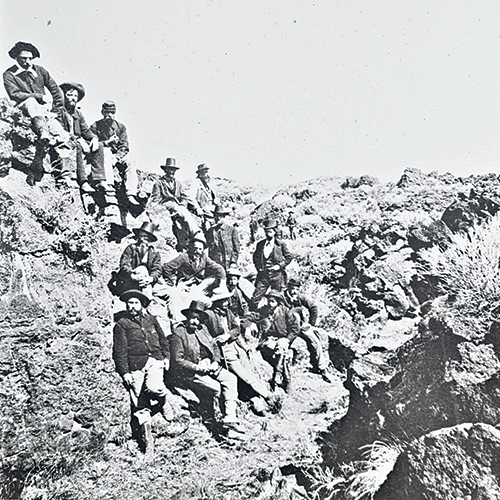

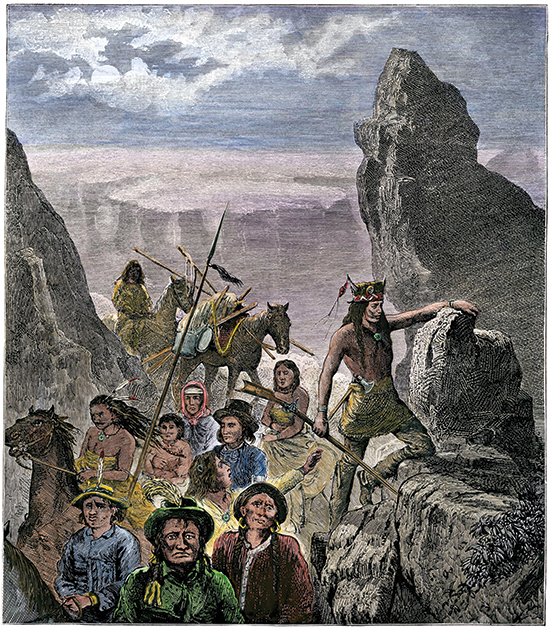

Unlike the fast-moving cavalry conflicts of the Plains, the Modoc War was fought as a siege, a setting the post–Civil War Army considered to its advantage, at least on paper. Appointed by Brig. Gen. Edward Canby, commander of the Department of the Columbia, Lt. Col. Frank Wheaton assembled a 300-strong force of federal soldiers and militiamen from Oregon and California supported by two mountain howitzers. On the other side the Modocs fielded but 50-odd riflemen tasked with defending more than 100 villagers, including elders, women, children and at least one newborn. They were less an army than a band of ragtag refugees.

Ordering a dawn assault on the Stronghold on Jan. 17, 1873, Wheaton was so confident of victory with his 6-to-1 advantage that he’d passed on reconnoitering the fog-shrouded battleground. That hubris proved his undoing. By day’s end nine soldiers and militiamen lay dead, 28 wounded, three mortally and others too seriously to return to action. The Modocs suffered not so much as a powder burn. Exploiting the Lava Beds’ tortuous terrain and the high ground of the Stronghold, the underdogs had flipped the strategic script.

News of the debacle so embarrassed the Army that Canby relieved Wheaton and took personal field command. At the same time prominent Oregonians lobbied U.S. Interior Secretary Columbus Delano to appoint a peace commission and perhaps negotiate a less costly end to the conflict. Delano won over President Grant and General of the Army William T. Sherman to the plan, declared a truce in the Lava Beds and selected the commissioners.

Like Wheaton’s assault plan, the peace commission looked better on paper than in practice. The problem was its personnel. Delano named as chair Alfred Meacham, who had served as U.S. superintendent of Indian Affairs in Oregon when the Modocs were reduced to eating their horses on the reservation. They blamed Meacham for that misfortune. Then there was commissioner Jesse Applegate, the trailblazer, who for years had been fomenting war on the sly. His goal was to drive the Modocs off their land and turn it into a ranching empire for himself and cattle baron Jesse Carr. The Modocs knew what Applegate was up to and justly suspected his motives.

As the peace commission was assembling, the press arrived to cover the paused war. In an expensive gambit the New York Herald, the leading East Coast newspaper, had dispatched reporter Edward Fox. In addition to Fox’s salary, the paper paid for his lengthy reports to be telegraphed word by pricey word to New York. Publisher James Gordon Bennett Jr. considered it a strategic investment. Only months earlier the Herald had scored a journalistic coup when it subsidized Henry Morton Stanley’s headline-grabbing search for missing African explorer Dr. David Livingstone in East Africa. (Stanley’s greeting, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume,” resonates today.) Bennett challenged Fox to pull off something as big and flashy, and hopefully profitable, from the Modoc conflict.

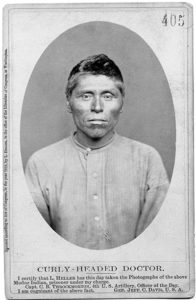

Curley Headed Doctor, a shaman who’d been leading an early version of the Ghost Dance to rouse the Modocs spiritually, saw the conflict as an apocalypse that would wipe out the settlers and resurrect the old days

Fox delivered. The reporter insinuated himself into a party of local settlers heading into the Stronghold to arrange a meeting with the peace commission. The Modocs lacked experience with newspapers, yet they recognized in Fox an unusual opportunity to get out their story to a wider audience. In the resulting published account of his overnight adventure among the Modocs, Fox laid blame for the war mostly on Oregon settlers like Applegate who coveted the tribe’s land. Yet the story won nationwide notice less for its advocacy than for Fox’s plucky reporting.

Meanwhile, the peace commission was making little headway. Already skeptical of Meacham and Applegate (the latter of whom resigned in disgust), the Modocs came to distrust Canby. Taking advantage of the truce, the general reinforced his original 300 men to some 1,000, added four Coehorn mortars to the artillery and moved his camps to the very doorstep of the Stronghold—on the west from the Van Bremer Ranch to the camp of field commander Colonel Alvan Gillem, and on the east from Scorpion Point to Hospital Rock. The final straw came when a cavalry patrol made off with most of the Modocs’ remaining horses, and Canby refused to return the animals. With that the Modocs knew they were cornered.

The tribe split over what to do. Captain Jack, Scarface Charley and several others argued for surrender, trusting the U.S. government would treat them well. Curley Headed Doctor, a shaman who’d been leading an early version of the Ghost Dance to rouse the Modocs spiritually, saw the conflict as an apocalypse that would wipe out the settlers and resurrect the old days. He advocated an all-out fight. His son-in-law, Hooker Jim, agreed, less from prophetic fervor than out of fear a surrender would land him and his eight accomplices atop the gallows for having slain settlers. Regardless, the pair convinced most Modocs to join them in an act of existential desperation—specifically, to set up a meeting with the peace commission, then attack with concealed weapons. Captain Jack had little choice but to bow to the majority, though he chose Canby as their target.

Toby Riddle, a Modoc woman serving as a translator for the Army, learned of the assassination plot and informed Canby. The general dismissed her as a hysterical alarmist before heading off with the rest of the peace commission to the meeting site about a mile from the Stronghold. There the Modoc delegation waited around a sagebrush fire. The date was April 11, 1873—Good Friday.

On arrival Canby handed out cigars and entered into conversation with Captain Jack. He advised the Modocs to surrender and trust him to find them a safe reservation somewhere warm, an offer he’d made repeatedly in vain. He also insisted the soldiers would remain until the parties reached a settlement. Suddenly, Captain Jack stood, shouted an order, drew a pistol and pointed it at Canby. Dumbfounded, the general froze, even when the handgun misfired. Canby remained seated as Captain Jack re-cocked the revolver, squeezed the trigger and sent a slug into the general’s brain. A second shot to the head and a knife to the neck finished Canby.

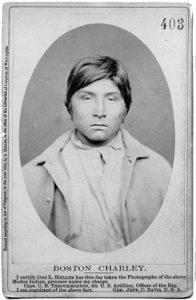

Meanwhile, Boston Charley put two rounds into the chest and head of the Rev. Eleazar Thomas, a Methodist minister who had replaced Applegate on the peace commission, and Schonchin John put four bullets into Meacham. Later rescued by troopers that responded all too slowly to the sound of gunshots, Meacham survived, albeit permanently scarred and partially disabled.

As headlines screamed THE RED JUDAS and declared Canby and Thomas martyrs, public opinion pitted the eternal forces of good (the U.S. Army) against the eternal forces of evil (the Modocs)

Under widely understood tribal rules of engagement in northeastern California, killing the other side’s leader would prompt that side to retreat, and the Modocs expected their surprise strike to have just that effect. They had badly miscalculated. As news of the killings hit newspapers from West Coast to East, the Modoc War escalated into a cosmic conflict. No longer was it a matter of rounding up a few Indians who had gone off reservation. As headlines screamed THE RED JUDAS and declared Canby and Thomas martyrs, public opinion pitted the eternal forces of good (the U.S. Army) against the eternal forces of evil (the Modocs). Any chance for compromise vanished, and the Modocs were put on the fast track to destruction.

To ensure that outcome, Sherman chose as Canby’s replacement the ironically named Colonel Jefferson C. Davis, a senior Union officer whose ruthlessness during the 1864 March to the Sea he had admired. However, Davis first needed to travel from Indiana to the Lava Beds, a journey sure to eat up most of two weeks. Loath to stay the hand of vengeance that long, Sherman telegraphed Colonel Gillem, the interim commander, to hit the Modocs with “an attack so strong and persistent that their fate may be commensurate with their crime. You will be fully justified in their utter extermination.”

Gillem served up that assault on April 15. Attacking the Stronghold from both west and east, the soldiers cut the Modocs off from their water supply at Tule Lake and harassed them with Coehorn mortar fire. After nightfall on the second day most of the Modocs—men, women, children and elders, with their dogs and horses—slipped out of the Stronghold along an unguarded narrow pathway, successfully threading the needle between Warm Springs scouts on one side and Army artillerymen on the other. A few Modoc sharpshooters remained behind to reinforce the deception. The others headed for ice caves in the southern Lava Beds that offered both cover and water. The Army had lost seven killed and 13 wounded in the action, the Modocs three warriors and a handful of women.

For 10 days the stealthy Modocs remained so well concealed in their new haunts that they were able to ambush a 67-man patrol as the unsuspecting troopers took a lunch break. The Battle of Sand Butte, named for the high ground from which the far smaller force of Modocs fired down on the lounging soldiers, was the Army’s costliest engagement of the war. Nearly two-thirds of the patrol was wounded or killed, the death toll including every officer.

Yet even as the Modocs enjoyed their greatest martial triumph, they were dragging bottom. They had been living in the open for more than five months, were clothed in torn rags and worn shoes, and had but a small cache of dried beef remaining. So on May 10, when another attempted ambush at Sorass Lake went awry, the resistance fractured. One group headed west and north toward Lower Klamath Lake. The other, under Captain Jack, made for the canyons east of Clear Lake. Over the next three weeks the Modocs were run to ground, group by small group, and forced to surrender. On June 1 Captain Jack handed his Springfield rifle to a Warm Springs scout, shook hands and announced he was done. With that the shooting phase of the Modoc War came to an end.

Colonel Davis, as befitted his reputation, made plans to hang most of the surviving Modoc men on the spot, starting with the Indian who killed Canby, Captain Jack. The gallows had just been completed when Davis received orders from Washington to stand down. Sherman and the Grant administration had opted for a final solution with a greater gloss of legality than summary execution.

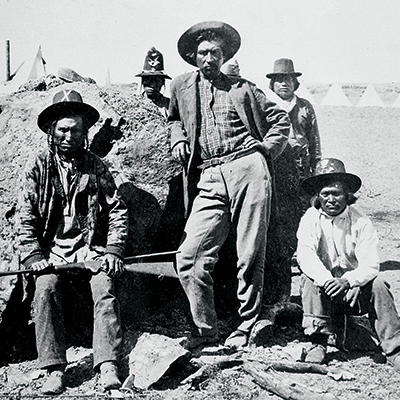

Thus it was in early July a military commission at Oregon’s Fort Klamath tried Captain Jack, Schonchin John, Boston Charley and three other Modocs for war crimes in the killing of Canby and Thomas, the only American Indians ever so charged. While a military commission may sound like due process, the transcript shows the proceeding to have been little more than a show trial. After only four days of proceedings the Modocs were convicted and condemned to hang.

The execution, a public spectacle before a crowd of some 2,000, including the imprisoned Modocs and nearly all the Indians from the Klamath Indian Reservation, was carried out on October 3. At the last moment President Grant commuted the sentences for the two youngest of the condemned to life imprisonment on Alcatraz. As for the four who died on the rope, the indignity continued beyond public hanging. Soldiers carried the bodies to a tent, where a waiting Army surgeon decapitated them. The headless corpses were then returned to their coffins and dropped into unmarked graves. The surgeon later shipped the prepared skulls to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C., in a barrel labeled SPECIMENS OF NATURAL HISTORY.

The execution, a public spectacle before a crowd of some 2,000, including the imprisoned Modocs and nearly all the Indians from the Klamath Indian Reservation, was carried out on Oct. 3, 1873

The surviving 153 Modocs, who had been held in dismal conditions at Fort Klamath since before the trial, were ultimately exiled to the Quapaw Indian Agency in northeastern Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Although they soon earned a reputation for making the best of their circumstances, desperate conditions there were worsened by corrupt Indian agents who pilfered funds meant for food and medical care. Tuberculosis, pneumonia and malnutrition took a slow, steady toll. By the end of the 1880s the Oklahoma Modocs numbered only 88.

Their fate mirrored what was happening to California’s Indians as a whole. In 1846, when the United States took over from Mexico, the indigenous population numbered 150,000, the largest number of Indians in any American state or territory. By 1873 a genocidal campaign of war and attrition had whittled that number down to 30,000. Although military action concluded with the Modoc War, the demographic decline continued, the state’s Indian population dropping to little more than 15,000 by 1900.

Fortunately, the moral arc of the universe is long, and it bends toward justice. Today California once again boasts the largest Indian population of any U.S. state or territory—723,225 as of the 2010 census. The Modocs, living mostly in Oregon and California, number 1,640. A people slated for destruction has made its resilient way back. WW

Author Robert Aquinas McNally’s most recent nonfiction book is The Modoc War: A Story of Genocide at the Dawn of America’s Gilded Age (2017), which won a 2018 California Book Awards gold medal from the Commonwealth Club of California. Learn more about the author at ramcnally.com. Also suggested for further reading: Remembering the Modoc War: Redemptive Violence and the Making of American Innocence, by Boyd Cothran, and Murder State: California’s Native American Genocide, 1846–1873, by Brendan C. Lindsay.