BELGIUM WAS VITAL in the summer of 1914. It was a thriving center of industry, finance and international trade, and owned vast mineral deposits in its African colonies. Closer to home, Belgium was neutral in the looming conflict between the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary and the Triple Entente—France, Britain and Russia. That didn’t prevent Germany’s fearsome war machine from rumbling into Belgium in August of that year and encasing the peaceful constitutional monarchy in a malevolent “ring of steel.” The Great War had begun.

Germany’s occupation paralyzed Belgium. All international trade ground to a halt—a grave problem for a country that imported three-quarters of its food. Reserve stores of flour and other foodstuffs were quickly exhausted—and then the German army grabbed most of Belgium’s 1914 agricultural harvest. Worse, the generals made clear that, though it violated international war protocol, they were not going to supply food to Belgium’s 7.5 million people or to the 2 million people in the swath of northern France that they also occupied. Germany had supply difficulties of its own because Britain’s Royal Navy had established a military blockade of the North Sea, cutting off Germany and the other Central Powers. The Germans argued that Belgium’s incipient food crisis could be averted if Britain would lift its blockade, but since that was out of the question the effectively imprisoned people of Belgium and northern France faced the grim prospect of malnutrition and starvation.

In September a delegation from Belgium, including Émile Francqui, a prominent banker, and Hugh Gibson, first secretary of the American legation in Brussels, arrived in London to plead for help getting food into the country. The U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom, William Hines Page, summoned an American expatriate to the embassy to meet with the group—a reserved, brusque, well-connected businessman said to possess an “indomitable will.” In 1914 Herbert Hoover was one of the world’s preeminent mining experts. He’d spent most of the previous 20 years tramping in remote corners of the world, managing mines, making deals and profiting from what he later called “the Golden Age of American engineers in foreign countries.” After graduating from Stanford University in 1895 with a degree in geology, Hoover worked in Australia, Burma and New Zealand. In Tientsin, China, in 1900, he and his wife, Lou Henry (also a Stanford-trained geologist), survived a monthlong siege of the city’s foreign settlement during the nationalistic frenzy known as the Boxer Rebellion. On the eve of World War I, according to biographer George H. Nash, Hoover was a director of 18 mining and financial companies with a combined 100,000 employees. He was a millionaire and had stakes in sundry mines potentially worth many times more. He had spent the last several years in London, managing a consultancy and living comfortably.

Hoover lacked social graces but was a tenacious problem-solver with one con-trolling passion, according to Nash—“a determination, a drive, to succeed.” He’d already put his administrative skills to work solving a crisis of the Great War. When the fighting started, some 150,000 American tourists and expats were stranded in Europe. Most eventually made their way to London, where they found banks closed and ships diverted to military purposes. Hoover came to their rescue, organizing, with the help of several engineering colleagues, a successful effort to secure passage for all back to the United States. The job involved a lot of creative financial work for the many people who didn’t have the money to get back to America.

Now Page, Gibson and Francqui urged Hoover to lead a food relief effort for Belgium. Francqui noted Hoover’s wide administrative experience, knowledge of the world and the fact that he had the confidence of U.S. and European ambassadors. And importantly, Hoover was an American and, thus, neutral. Hoover himself wasn’t daunted by the administrative challenge of Belgian relief—the purchase, overseas shipment and internal transport of large quantities of material; he said, “Any engineer could do that.” But, he acknowledged, “there were other phases for which there was no former human experience to turn for guidance. It would require that we find the major food supply for a whole nation; raise the money to pay for it; get it past navies at sea and occupying armies on land; set up an agency for distribution of supplies for everybody justly; and see that the enemy took none of it. It was not ‘relief’ in any known sense. It was the feeding of a nation.”

Herbert Hoover was 40 years old and ready for a career change. He once said, “If a man has not made a fortune by 40 he is not worth much,” but now, he told a friend, “Just making money isn’t enough.” He’d been yearning for a career in public service and aimed to get into the big game. There was nothing bigger, as one relief official later put it, than the “heart-breaking, nerve-stretching race against death” in Belgium. So Hoover stepped away from his business duties and accepted the relief job, on the condition that he receive no salary and be given free rein, as chairman, to run the organization.

What came next was one of the greatest humanitarian achievements in all of history. Hoover and a small group of men—Allied diplomats and businessmen, many of whom were American engineers—created the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) that, with the help of private donations, massive Allied government grants and loans and thousands of volunteers, would feed nearly 10 million people in a war zone every day for four years. Large and complex, and at risk of being shut down at any time, the CRB was an operation without precedent, not that Hoover grasped the enormity of the undertaking at first. He figured the war would last less than a year. “The knowledge that we would have to go on for four years—to find a billion dollars, to transport five million tons of concentrated food, to administer rationing—was mercifully hidden from us.”

Hoover did not just work on behalf of Belgium. After the United States declared war on Germany, in April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson appointed him director of the new U.S. Food Administration, charged with stimulating farm production and reducing food consumption for the American war effort while continuing his CRB duties. And then after the war, as a member of the Supreme Economic Council and head of the American Relief Administration, Hoover organized food relief for hundreds of millions of people in 26 nations facing severe food shortages—including Germany, Poland and Bolshevik Russia. His humanitarian efforts turned the tough, taci-turn Hoover into an international and American hero—and after a stint as secretary of commerce for Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he was elected president in 1928. His timing, of course, was terrible: Hoover’s presidency coincided with the worst-ever U.S. depression. Hoover, a Republican, tried to revive the economy but his initiatives came to nothing, and he was thrashed in his reelection bid by Franklin D. Roosevelt. Hoover’s failure to save the U.S. economy tarnished his reputation—so much so that he is forgotten for what Russian author Maxim Gorky called his “unique, gigantic achievement”: saving millions of Europeans from starvation.

A resourceful man with an extraordinary energy level, Hoover jumped into action after accepting the Belgian relief job. Even before the CRB was formed on October 22, 1914, he’d called a broker and placed an order to buy 10 million bushels of Chicago wheat futures, knowing that the war and Belgian food needs were sure to raise prices. After the organization was created, as a private partnership, Hoover put various engineering colleagues in key roles. One took charge of the CRB’s London office, another the Brussels office and a third was assigned to open the shipping office in Rotterdam, Holland, designated as the destination for all Belgian food shipments. A fourth engineer took command of purchasing and shipping for the operation. CRB representatives began leasing cargo ships, and Hoover enlisted the support of ambassadors from the United States, Holland and Spain—noncombatants in the European war—“to make clear our neutral character and for their aid and protection in negotiations with the belligerent governments.” (After the United States, Holland and Spain played the most crucial national roles in Belgian relief.) When Hoover needed gutsy American volunteers to monitor the distribution of food in Belgium, he found 15 American Rhodes Scholars at Oxford University. To preempt the possibility of accusations of financial malfeasance, Hoover persuaded a leading British auditing firm to handle the CRB’s books at no charge.

Hoover understood how news stories influenced public opinion, and he’d collected a lot of noteworthy American and British journalist friends. He asked the Associated Press general manager in London to “ventilate” the poignant Belgian story—a plucky nation caught between the millstones of an occupying army and a naval blockade—and publicize the creation of the CRB and the dire need for charitable donations. The international response was strong. Belgian Relief Committees were set up in 40 American states as well as countries around the world—Australia, Argentina, Japan and South Africa, to name a few—and $2 million was raised in a few weeks. The CRB’s job was to get food into Belgium under the aegis of American neutrality. A separate Belgian organization headed by Francqui, the Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation, would, with thousands of volunteers, transport it to provinces and regions and then to thousands of local communes, from which it would be distributed, under the watch of burgomasters and mayors, to individuals and families.

Within a week the CRB could claim success. With informal German permission, some 20,000 tons of cereals, peas and beans had been picked up in Holland and delivered to large Belgian cities by canal boats. And within six weeks, wrote Hoover, “we had delivered 60,000 tons of food from overseas,” thanks to the help of British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey, who secured temporary permits for CRB ships to pass through the blockade and dock at Rotterdam. “The cities were saved for the moment,” wrote Hoover in his memoir.

Then came a raft of difficulties. By January 1915, the CRB had raised and spent about $15 million—most coming from the foreign assets of Belgian banks—and had millions of dollars of debt. “We were approaching bankruptcy at a high speed,” wrote Hoover. He estimated that at least $12 million a month was needed to feed the Belgians and residents of northern France. And an additional $10 million of food had to be in the pipeline at all times. As Hoover realized, “There was no hope of saving the Belgian people unless we could get government support somewhere.”

Then came a raft of difficulties. By January 1915, the CRB had raised and spent about $15 million—most coming from the foreign assets of Belgian banks—and had millions of dollars of debt. “We were approaching bankruptcy at a high speed,” wrote Hoover. He estimated that at least $12 million a month was needed to feed the Belgians and residents of northern France. And an additional $10 million of food had to be in the pipeline at all times. As Hoover realized, “There was no hope of saving the Belgian people unless we could get government support somewhere.”

He meant Britain and France. The British, for one, were not of a mind to support the CRB. Most of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s Cabinet, including Minister of War Lord Kitchener, Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George and First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, opposed the idea of delivering food to Belgium, fearing that it would end up in the bellies of German soldiers. Undeterred, Hoover personally confronted Asquith, asking for regularized passage of CRB ships through the blockade along with financial assistance. Asquith was amenable to the idea of regularized North Sea passage, but any financial help, said one Foreign Office official, was “impossible.”

Hoover wouldn’t accept that. He was both intuitive and logical, helped by what he described as a “naturally combative disposition.” He set off for Berlin, the first of 40 North Sea crossings he would make as CRB head, “to besiege the German government at the top directly and on all fronts.” The Big Chief, as Hoover was known within the CRB, imposed his personality on the generals and got what he needed most—a written guarantee that all imported food would be free from requisition by the German army. What’s more, Germany officially agreed that CRB foodstuffs could be brought into Belgium by way of Holland, that CRB officials would have freedom of movement in Belgium, and that oceangoing CRB ships would be left alone by German submarines. It was a major breakthrough. Vernon Kellogg, a top CRB official, noted in his book about the relief effort, Fighting Starvation in Belgium, “The German government [in Brussels and Berlin] has shown itself consistently favorable in principle, even if often troublesome in specific matters, to the Commission’s work.”

Hoover, sensing that the German concessions might create some negotiating leverage with the British, made another impassioned pitch to Lloyd George. This time the chancellor was moved—and two days later it became clear that he, Grey and Asquith had overruled Kitchener and Churchill: Britain agreed to contribute nearly $5 million a month to the “Hoover Fund.” The CRB chairman then traveled to Paris and met with the French minister of foreign affairs who was also reluctant to reward German barbarities with relief food. But a day after Hoover’s return to London, a French banker appeared at the CRB office and presented him with two checks from the French government totaling $7 million, after which the country contributed roughly $5 million every month for relief in both Belgium and northern France. Lord Eustace Percy of the British Foreign Office said that Hoover’s “very soft heart and very hard head alike prompted an instinctive attitude to all governments which could best be summed up in the words ‘kindly get out of my way.’ ”

The CRB was in business—and quickly became a sophisticated operation managed with what Hoover called “engineering efficiency.” Functioning almost like a government entity, the committee had its own flag (triangular, with the letters CRB stitched in red), ships, letterhead, buyers and accountants. The New York office bought staples from around the world—corn and meat from Argentina, beans from Manchuria, rice from Burma—wherever they could get the lowest price. The CRB leased about 60 oceangoing cargo ships to transport food and clothing, and 150,000 tons of material arrived in Rotterdam every month. For safety the ships all displayed CRB flags, pennants and deck clothes and followed specific routes to Rotterdam laid out by the Germans. Still, over four years the CRB lost about 20 ships, a handful of them sunk by German subs. Germans inspected every ship docking in Rotterdam—any discovery of contraband could have ended the entire relief effort—and then its cargo was quickly offloaded onto canal boats. Belgium’s excellent transportation system, with its many miles of canals and extensive light rail, was a logistical saving grace. Some 5,000 canal boats made deliveries from Rotterdam to Belgian cities, from which light rail and horse carts moved the food to provincial and district warehouses, and then to 4,200 communes.

CRB relief in Belgium was split between basic “provisioning” for the citizenry and a “benevolence” operation for the destitute, meaning the poor and the hundreds of thousands of people thrown out of work by the war. The provisioning unit took control of every mill, bakery, slaughterhouse, dairy and restaurant in the country, while the charity group “became our effective armor against periodic attempts by British and German militarists to suppress or restrict our activities,” explained Hoover.

Feeding Belgium was no simple matter. Biographer Nash, in The Life of Herbert Hoover: The Humanitarian, quotes CRB delegate Joseph C. Green on what the equitable distribution of food entailed, with bread as an example. “First the Provincial Representative has to figure out periodically the exact population of his province, and the exact quantities of native wheat and rye and of imported grain necessary to cover a certain period. This he reports to Brussels, and Brussels to London….In the meantime, Brussels has decided upon the exact quantities to be shipped to each mill in the country.”

That was just the beginning. “When the flour is finally milled, the real work of distribution begins. Sacks must be provided and kept in rotation. The exact quantity of flour required by a given Commune for a given period must be ascertained. Shipments by canal or train or tram or wagon must be made to every Commune dependent upon the mill. Boats and cars and horses must be obtained….When the flour has reached the local committee, it must be distributed among the bakers in accordance with the needs of each. Baking involves yeast, and the maintenance of yeast factories, and the disposal of byproducts….All this involves financial problems, and bookkeeping, and checking and inspection, all along the line; and the whole process to the tune of endless bickering with Germany authorities high and low.” Bakers were closely monitored to ensure that they did not hoard flour or otherwise violate CRB rules. “We certainly did have trouble with the bakers,” wrote CRB official Kellogg. Those suspected of violations were brought before a “baker’s court” and, if found guilty, Monsieur le Boulanger had his baking privileges suspended.

Ration cards were sold or given to every family or citizen. Early on, most Belgians paid for their cards. Prices were kept reasonably low. The price of wheat and flour in Belgium never exceeded its price in London or Paris and was often lower. In fact, cash receipts from rations surpassed the needs of the charity group, so the surplus money was used to pay police and teachers, in the latter case so schools could be kept open. The situation further improved in 1915 when the Germans agreed to reserve for the civilian population all wheat, barley, rye and oats grown in Belgium—and that accord was subsequently extended to other foods.

And what did the Belgians eat? The basic daily ration consisted of bread, bacon, lard, rice, dried beans and peas, cerealine (similar to corn flakes), potatoes and brown sugar. In total it amounted to roughly 1,800 calories—sufficient to maintain health and fight off disease but, according to Kellogg, “hardly more than half enough calories for a man at work.” Each full ration cost the CRB about 8 cents a day. Added Kellogg: “It is a ration worked out very carefully to make money go as far and effectively as possible in providing a scientifically balanced, readily transportable and storable and easily divisible food supply to a people whose whole eating could be controlled and directed.”

Many Belgians lived on this ration almost exclusively for more than three years. Those who could afford it bought vegetables, fruit, milk, eggs and some meat. Farm families kept enough of their harvest to feed themselves and sold the rest to the CRB at a profit. The CRB and its Belgian counterpart meticulously monitored food consumption, constantly adjusted the volume of foodstuffs transported to particular locales—and wasted no money. Amazingly, an organization that raised and spent more than $925 million kept its overhead costs below 1 percent.

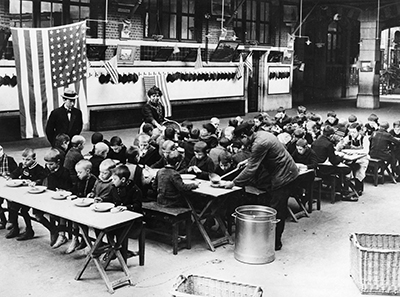

Feeding the children was a priority. “It was our task to maintain the laughter of the children and not dry their tears,” said Hoover. In addition to establishing soupes for the poor, the CRB set up hundreds of canteens to provide young Belgians with a hot meal every day at noon—a hearty stew, condensed milk and other staples. Children need fat in their diet, so the CRB developed what Hoover described as a “big, solid cracker with fats, cocoa, sugar and flour, containing every chemical for growing children.” One was served every day to 2.5 million youngsters and expectant mothers. “The emblem of Belgium during the war should have been a child carrying a soup bucket,” wrote Hoover in his memoir. “From the rebuilding of the vitality in the children came the great relieving joy in the work. The troops of healthy, cheerful, chattering youngsters lining up for their portions, eating at long tables, cleaning their own dishes afterward, were a gladdening lift from the drab life of an imprisoned people.” When the war ended it was found that the mortality and morbidity rates for children in Belgium and northern France were lower than at any time in their history.

Still, problems were constant: German soldiers arbitrarily arrested CRB couriers. Canals froze in the winter. Food was smuggled across the border with Holland. Hoover regularly shuttled between London, Paris, Brussels and Berlin to resolve financial, logistical, political and military complica-tions, which meant finding agreement be-tween two European allies that were often at odds and three different German governments—one in Berlin, the others in Brussels and Charleville, France. The worry that the Germans would steal CRB food never materialized. “I can honestly say that the Germans got practically none of the food,” wrote Kellogg.

Through all the despair, a spirit of sacrifice and humanity prevailed. Some 50,000 Belgian volunteers shouldered the relief work every day. Many were women, who ran the soup kitchens and charity clothing centers. When donated sweaters from America arrived—part of a total of 55 million tons of clothing donations—seamstresses would unravel them and knit them into shawls, the Belgian version of a sweater. Wrote Hoover: “The women developed a zeal that sprang from the spiritual realization that they were saving their race.” And, in turn, the CRB took a turn at helping the women. Some 40,000 of the country’s talented female lace workers were made unemployed by the German invasion. The CRB put them back to work making lace and paid them for their output. After the war the CRB owned $4 million worth of lace that was sold with “substantial dividends to the lace workers.”

When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the CRB altered its operation. All Americans were pulled from Belgium and replaced by Dutch and Spaniards. Hoover’s appointment as head of the Food Administration meant a move from London to New York. By then the Germans were engaged in unlimited sub warfare, and the Belgian relief situation had become more difficult. Some 60 percent of Belgians were unemployed, destitute and daily receiving food from a soupe or some other form of assistance—tens of millions of people. The CRB had fewer cargo ships, which, when combined with global food shortages brought on by the war, meant smaller rations.

Still, Hoover continued to run the CRB, and the CRB kept the food moving. American money began to finance most of the relief effort, American soldiers joined the war effort, and the long, vicious military conflict came to an end on November 11, 1918. That didn’t end Belgian relief, however: Hoover opted to keep the CRB going for another six months, until international commodities trading and shipping could properly resume. When the organization was liquidated, the CRB had a surplus of $35 million. Hoover gave $18 million of it to various Belgian universities and other educational institutions as cash gifts, and with the remainder created two U.S-Belgian cultural and educational foundations that still exist.

Led by its “master of efficiency,” as the British newspaper The Independent called Hoover, the CRB had persevered and kept a nation alive. Hoover and his staff refused to retreat before the “unremitting pressures and troubles that beset [them] at every turn,” according to Nash. “A man of lesser nerve—or less than total commitment to his mission—would have had his ships requisitioned by the Admiralty, his independence whittled away by the Germans….Not Hoover. Time and again the CRB’s desperate circumstances required the intervention of a man of force. It is doubtful that the relief work would have lasted if a gentler, less assertive person had been at the helm.” American ambassador Walter Hines Page agreed, saying of the Commission for Relief in Belgium: “There never was anything like it in the world before, and it is all one man, and that is Hoover.”

Hoover had established a global model for international relief, one that he carried over to central Europe and Russia after the war when he became what General John J. Pershing called “the food regulator for the world.” Hoover wasn’t a sentimental man, and he didn’t like the idea of getting European decorations. “When all is said and done,” he said, “accomplishment is all that counts.” Still, he agreed to accept a singular honor from Belgian King Albert when he visited the country in August 1918: Ami de la nation Belge.

Richard Ernsberger Jr. is a senior editor at American History.

The “Man of Force” Who Saved Belgium originally appeared in the April 2014 issue of American History magazine.