The USS Yorktown (CV-10) steamed gently 30 miles off the coast of San Diego on a golden December morning in 1968. As the ship turned into the wind, its silhouette left no doubt as to its pedigree: This was a World War II–vintage Essex-class aircraft carrier, though with an angled flight deck that had been added after the war. But that was only one contradiction on this ship of contradictions.

Painted on the deck were the white lines that Japanese carrier pilots used to gauge wind direction at takeoff. Behind them was a raft of Japanese aircraft, or at least what appeared to be Japanese aircraft. And surrounding the aircraft were throngs of cheering sailors waving their hands and the white baseball caps favored by the Imperial Japanese Navy. These sailors, however, were American—the Yorktown’s crew.

The planes hurtled down the deck, over the painted lines, and lifted into the air. Beneath the black horizon line only their glowing exhaust pipes and navigation lights were visible, but once they rose into the orange sky their ominous shapes were clearly defined. Up they went, one after another, the roar of their radial engines deafening.

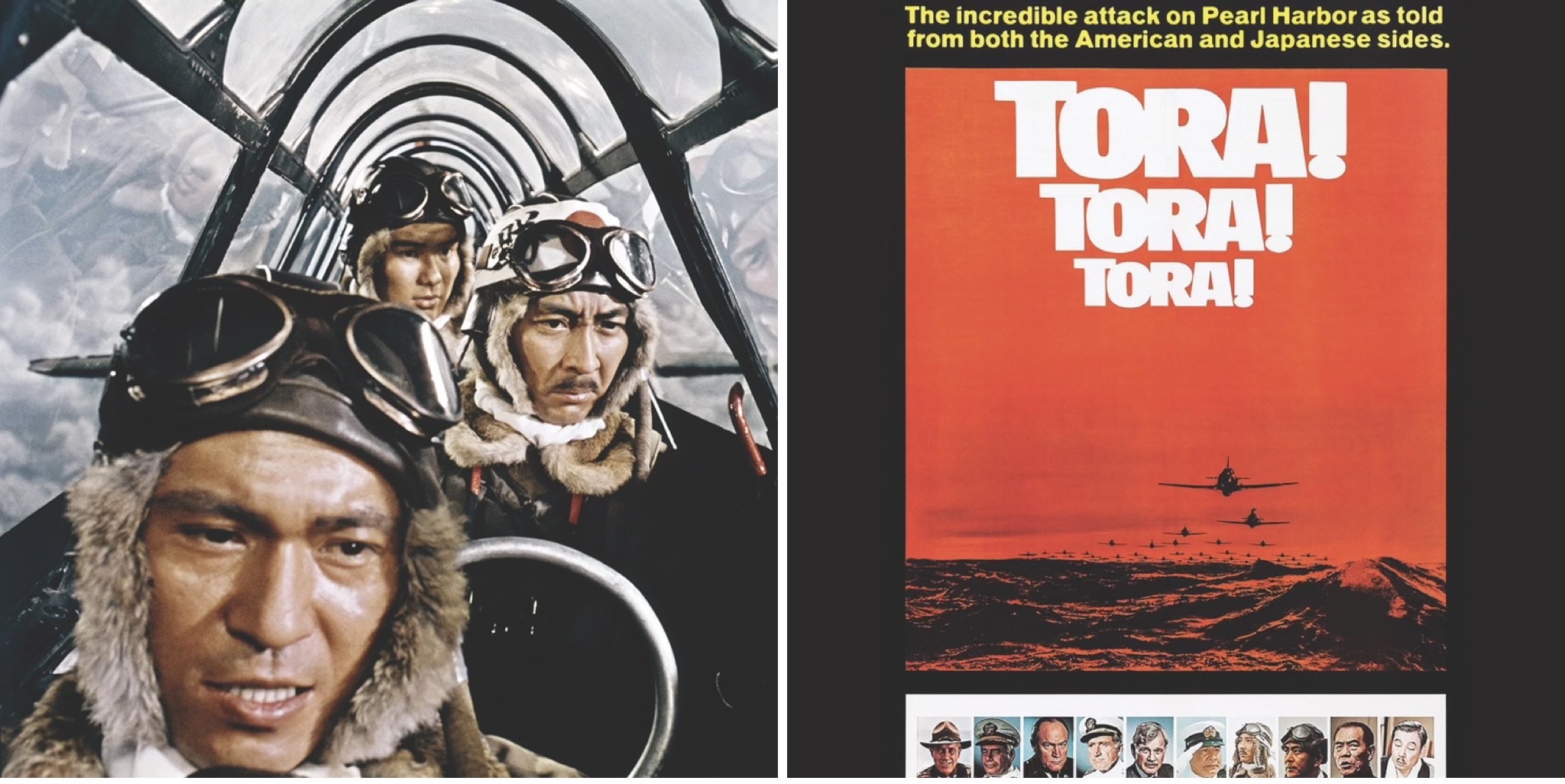

Panavision cameras captured it all, because the Yorktown was a movie set—a gigantic 36,000-ton movie set steaming in the Pacific—and this was the first day of shooting for a film unique in the annals of war movies: Tora! Tora! Tora! Twentieth Century Fox was making it to tell the story of the planning and execution of the bombing of Pearl Harbor from both the American and Japanese sides. It would premiere two years later, in 1970, after numerous false starts, delays, scandals, deaths, and ruined careers—even a threat of suicide—and it would be, for its day, one of the most complex, expensive, and seemingly cursed films ever made.

The aircraft rolling down the Yorktown’s deck were World War II–era American and Canadian trainers modified to look like Japanese carrier planes—Zero fighters, “Kate” torpedo bombers, and “Val” dive-bombers. Lynn Garrison, a retired Canadian Air Force pilot, was one of two plane wranglers responsible for building the air fleet. His partner had died during preproduction, one of two Tora! deaths. Now Garrison was among the pilots flying off the Yorktown, which had been hit by a Japanese bomb during the real war and was playing a supporting role as the Akagi, the attack force’s flagship.

In several days of shooting, Garrison would pilot a Zero, a Kate, and a Val. “With the Zero it was all of a sudden standing on its two wheels, tail up,” Garrison, now 81, recently recalled in a telephone interview from his home in Haiti. “With the 40 knots over the bow the thing was airborne almost immediately. It was a strange sensation. Sort of like an elevator.”

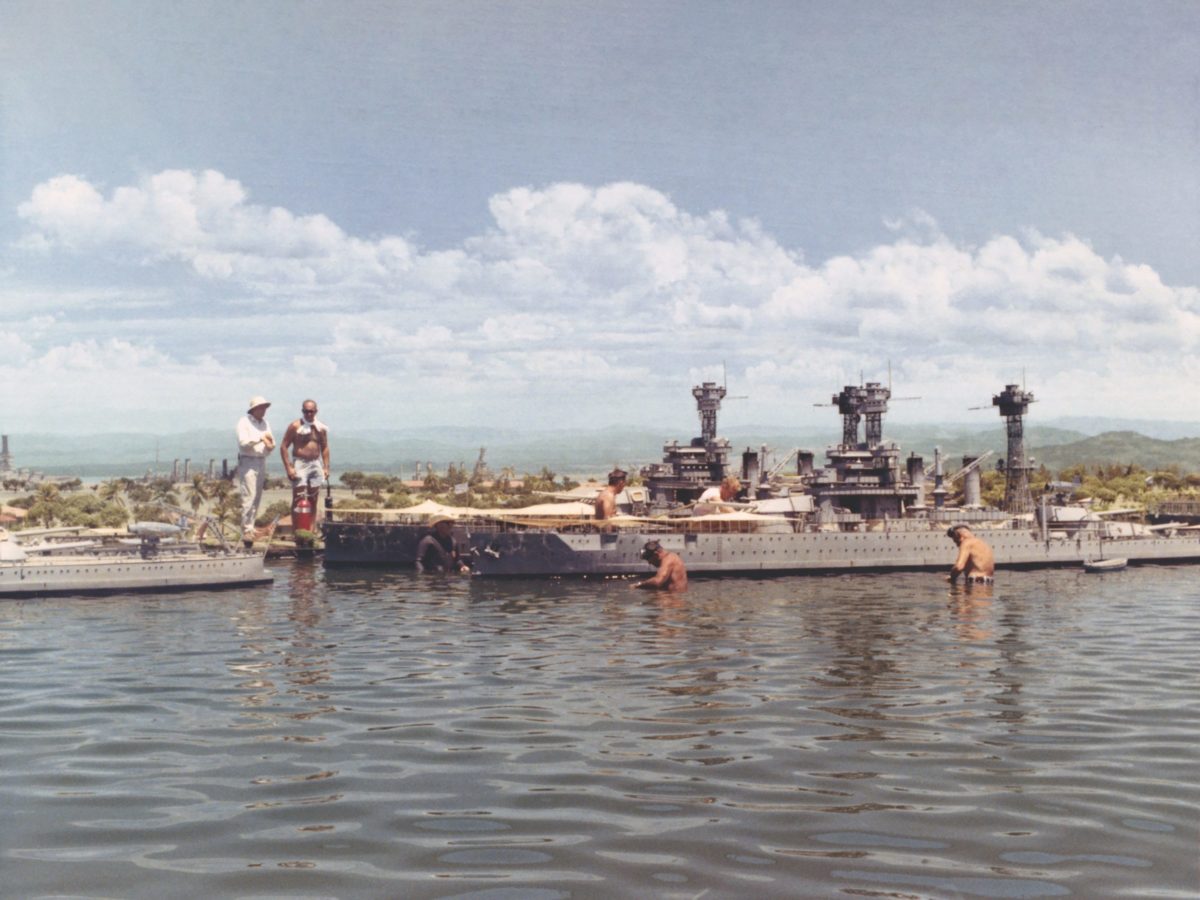

Blowing up battleships

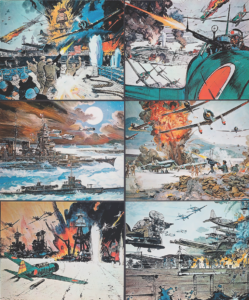

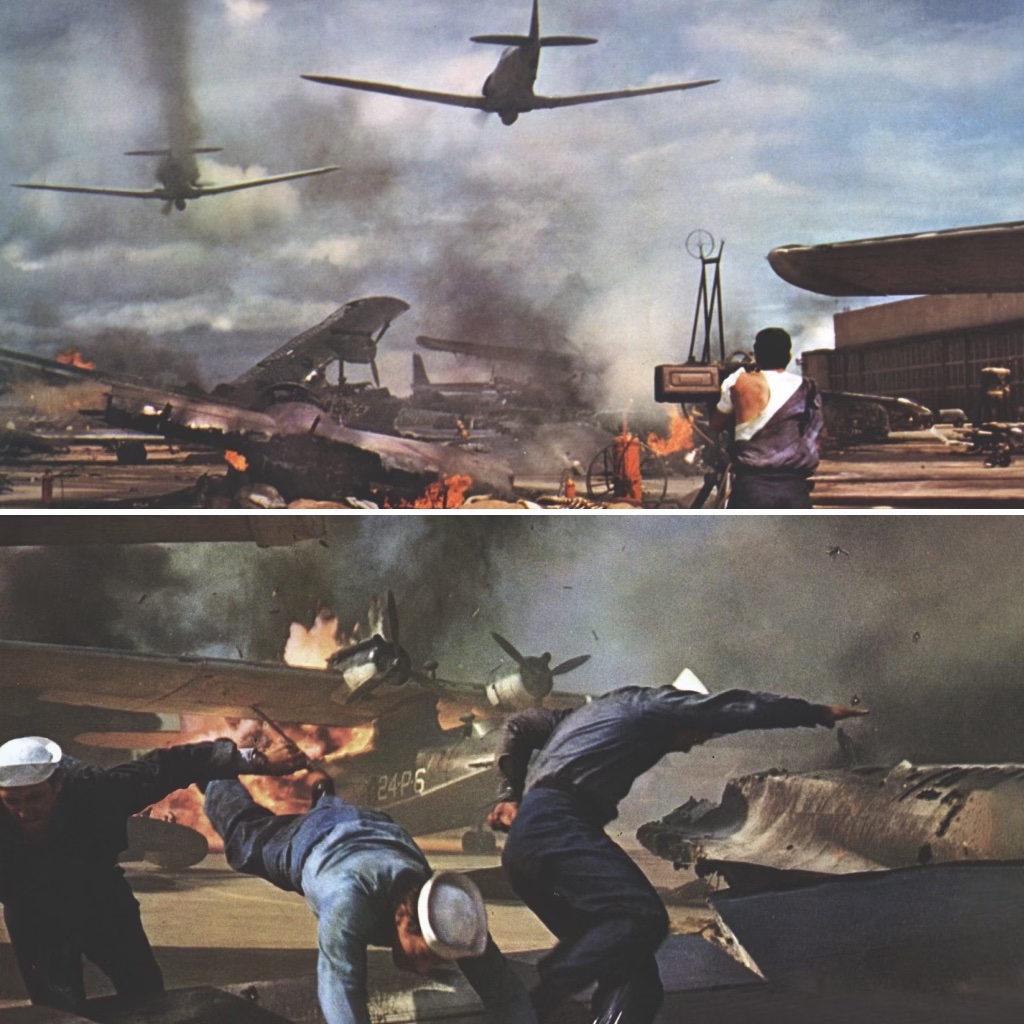

The takeoff sequence is just one striking set piece in a film filled with them, from the opening credits, shot aboard a life-size mockup of a Japanese battleship, to the attack itself—a frenetic, neon-orange Götterdämmerung of explosions and smoke and burning, drowning men that created a visceral sense of being under fire perhaps unmatched until the opening Omaha Beach sequence in Saving Private Ryan in 1998. Tora! Tora! Tora! was one of the last old Hollywood blockbusters, and the story of its creation is a raucous and at times even comic tale of movie making in the days before computer-generated graphics. In industry parlance, this was a movie made “practical”—in other words, if you wanted to blow up a battleship on film, you had to blow up a battleship.

But that isn’t what makes Tora! Tora! Tora! so different. This was not only a motion picture that went to extraordinary effort and expense to portray history as it was—down to using exact quotes in dialogue and, yes, modifying all those airplanes—but a film that managed to deepen two formerly warring nations’ understanding of a seminal event in their messy shared histories. It helped heal the lightly scabbed wounds of the Pacific War, then a recent memory, while also portraying the Japanese people far more honorably and through a far less racist lens than the vast majority of Hollywood films that had preceded it. And its influence has lingered in sometimes surprising ways in the decades since.

Tora! Tora! Tora! was the brainchild of Darryl F. Zanuck, the legendary chairman of Fox. With his severe features, piercing blue eyes, and giant cigar clamped between his teeth, Zanuck was a cliché of an old-time Hollywood studio boss. He’d gotten his start during the Silent Era and gone on to oversee some of Fox’s greatest creations. But by the 1960s, the old ways just weren’t working anymore. Upstart “auteurs” were all the rage in cinema, while big studio epics like Fox’s bloated Cleopatra flopped one after the other.

Zanuck’s son, Richard, himself a cliché of the Hollywood playboy, was Fox’s head of production. The studio needed a blockbuster. So Zanuck and his right-hand man, producer Elmo Williams, resurrected the formula they had successfully used in The Longest Day (1962), their star-studded re-creation of D-Day. This time they would tell the story of Pearl Harbor. Williams was a gregarious studio system veteran and former editor whose credits included High Noon—for which he had won an Academy Award—and who had conceived and directed The Longest Day’s battle sequences. Now he’d been handed the challenge of his lifetime. And right away he met it with a big idea: Not only would the story of Pearl Harbor be told from both sides, but it would be told by both sides—American filmmakers would create the American sequences, and Japanese filmmakers would write and produce the Japanese sequences. Both halves would then be edited into a cohesive whole.

TWo movies in one

This was an extraordinary conceit. Just 24 years earlier the two countries had been locked in the greatest conflict in human history. Most Americans saw the bombing of Pearl Harbor as a dastardly sneak attack executed by a dishonest people at a time of international tranquility. The truth was that it was a bold military stroke by a highly competent professional navy at a time of tense relations and that it succeeded at least partially because of American errors. And it was not supposed to have been a surprise at all—it was meant to have followed an ultimatum that, to the Japanese at least, amounted to a declaration of war.

While the Germans in The Longest Day spoke their native tongue and were played by notable German actors, and some scenes were shot on actual battle locations, the film still embraced some movie-making conventions, like a few too many moments of comic relief, a French starlet (Daryl Zanuck’s girlfriend) playing a sexy French resistance fighter, and John Wayne playing, well, John Wayne. None of that for Tora! Williams and the Zanucks decided, among other things, to cast noted character actors in the lead roles based on their physical resemblance to the actual people.

A team of writers set to work, using two books as source material for the American sequences: Gordon W. Prange’s Tora! Tora! Tora! The Pearl Harbor Story (1963), which would later be published as At Dawn We Slept, and Ladislas Farago’s The Broken Seal: The Story of Operation Magic and the Pearl Harbor Disaster (1967), which examines the United States’s successful, but fumbled, breaking of Japanese naval codes.

Darryl Zanuck and Williams had another reason to aim for accuracy. Both men felt that history had unfairly maligned Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, who’d been in charge of the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor. Their film, they hoped, would set that right.

Fox struck public relations gold with the joint-production gimmick; the press ate it up, especially with a new war raging in Asia, in Vietnam. Even though a premiere was years away, the studio began promoting the film as “The Most Incredible Movie Ever Made.” But then Williams took the idea a step further: He hired the most famous Japanese director of them all—indeed, one of the world’s most renowned filmmakers: Akira Kurosawa.

Williams would come to regret it.

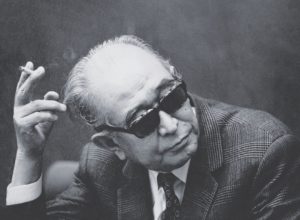

enter kurosawa

Kurosawa’s cinematic masterpieces included Rashomon, whose multiviewpoint storytelling was a revelation to Western audiences, and Seven Samurai, whose thrilling action changed the minds of anyone who thought Japanese films were somber and serious. A master of pacing, plot, and lightning-fast violence, he was the best-known Japanese director in the United States.

Kurosawa jumped at the chance to direct Tora!, as he’d long wanted to break into Hollywood and had also toyed with the idea of making a movie about Pearl Harbor. His involvement prompted a new round of breathless headlines. “This movie will be a record of neither victory nor defeat but of misunderstandings and miscalculations,” Kurosawa said during a press conference in April 1967. “As such it will embrace the typical elements of tragedy. I want to look straight into what it might mean to be a human being at a time of war.”

Just as Zanuck and Williams were interested in the character of Kimmel, Kurosawa was fascinated by the character of Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander of the Combined Fleet, who first conceived the attack. Yamamoto had famously argued against going to war with the United States, insisting it was a war that could not possibly be won. In the admiral’s grand contradiction—an officer who carries out his duties to the fullest even when he does not agree with the mission—Kurosawa saw an irresistible, even Shakespearean, tragic arc.

At the time, Kurosawa’s reputation in Japan was on the wane. Known for running his productions with such vise-like control that he had been nicknamed Tenno (“The Emperor”), Kurosawa threw himself into Tora! He and two of his longtime collaborators, sequestering in an inn to immerse themselves in the history of the Japanese side of the attack, pored over official records and produced a script that would have run six hours—without the American side. No fewer than 27 rewrites followed. They consulted numerous Japanese veterans, including Minoru Genda, the young commander Yamamoto had assigned to work out the logistics of the attack, whom Kurosawa hired as an adviser. Kurosawa also storyboarded practically every scene with his own drawings.

massive vision

Kurosawa conceived of the film’s opening: a massive “manning the rails” sequence on the battleship Nagato, in which thousands of sailors in their white uniforms line the decks to honor Yamamoto’s new appointment as the fleet’s commander in chief.

To achieve his vision, Kurosawa soon had an army of workers creating a life-size set of the Nagato on a beach on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu. At 660 feet long and 10 stories high, with a towering “pagoda” superstructure, it was the largest set ever built in Japan, an ingenious creation of plywood, concrete, and wires atop a forest of telephone poles. Its designer-architect was Tsukasa Kondo, an art director handpicked by Kurosawa (but not credited).

The faux battleship sat perpendicular to the Hibiki Sea so that when filmed from a low angle, it would appear to ride the currents. A separate set of the flight deck and superstructure of the Akagi, complete with a working aircraft elevator, was built parallel to the Nagato, allowing one to be filmed from the other, giving the cinematic impression of a grand fleet at anchor. Hordes of tourists crowded the beach to admire the twin monstrosities as they were being built, and at least one snowstorm—rare in that part of Japan—delayed construction. “For my father, completing the open set of the battleship Nagato and the aircraft carrier Akagi of ‘Tora! Tora! Tora!’ was the best job of his life,” Kondo’s son, Masashi, recalled in a recent email exchange. “It was my father’s pride that he was appointed by Akira Kurosawa, designed a huge set, and led a large staff as an art director to complete it. It didn’t matter if his name was credited or not.”

Kurosawa visited often, striding the teak decks, taking it all in from behind dark glasses. At 6 feet tall, the director towered over those around him.

obsession with accuracy

Williams’s obsession with historical accuracy went beyond the script and plot. The planes had to be just right too. This was an era in which every American boy who’d grown to adulthood knew his World War II planes by heart. So Williams brought in Garrison and his sometime partner, Jack Canary, who would also act as the film’s safety coordinator. The pair had worked with Williams on the 1966 film The Blue Max, creating an entire air force of replica World War I fighters—Fokkers, Pfalzes, and S.E.5s—but Tora! would require even more ingenuity. Williams wanted no fewer than 70 planes of different types. He wanted some to fly off real carriers and to drop torpedoes.

And he thought he knew where to get them: Why not travel around the Pacific to abandoned Japanese airfields and restore the planes that had been left behind? Canary and Garrison thought it over, talked it through, and went to the producer to disabuse him of that notion. The challenges were insurmountable.

First, the airfields were inland, so any wrecks would have to be helicoptered to barges before they could be transported across the Pacific. Second, Japanese planes had not been built to last, especially in the war’s later years; the zinc-aluminum alloy used in the airframes, for example, was especially susceptible to corrosion. Some planes in long-forgotten airfields had palm trees growing out of their cockpits. And of course the Japanese had lost the war, so most of their planes had been shot down or blown to bits on the ground.

Canary and Garrison had a better idea: to modify AT-6 Texans (or their Canadian Air Force cousins, Harvards) and a second similarly designed trainer, the Vultee BT-13 Valiant, so that they looked like Japanese planes.

Garrison, who was living in Ireland (where The Blue Max had been shot), set up a slide projector with his daughter’s help and used it to throw images of the Japanese planes on the wall over paper cutouts he made of the American and Canadian trainers. Then he took scissors and cut up the paper models, mixing and matching their parts so that they fit the images being projected on the wall, showing how easily these planes could be transformed: Texans and Harvards as Zeros, Valiants with their fixed landing gear as Vals, and sections of both planes to make Kates. Fuselages would be lengthened, wing shapes altered, canopies modified. Williams was sold. Garrison and Canary would get $1,000 for every plane they brought in, plus expenses.

creating an air force

Finding the planes, however, was easier said than done. In the years following World War II, militaries around the world had sold the trainers as surplus, often for as little as $300, and amateur pilots and collectors had snapped them up. But over the years they fell from use, and by the time Canary and Garrison started their hunt for the planes, many of them sat “lonely and unloved,” in Garrison’s words, in little airfields and even barns and backyards.

With two associates, Garrison crisscrossed the country in his own Piper Comanche to look at Texan-Harvards. Quite a few were unflyable. Rubber fuel hoses had ruptured. Cables were frayed. Canopies were rusted shut. Birds had nested in the engine wells or beneath the wings. Many had bad magnetos, the magnetized devices that delivered the electrical current to start the engine.

When Garrison found a good specimen, he bought it on the spot and then flew it himself across the country, barnstormer-style, back to Long Beach, California, where it would be modified at two aircraft companies, Stewart Davis Inc. and Cal-Volair, for use in the film. Garrison used roads and railroad tracks to navigate, stopping at random airfields to fuel and use the bathroom.

Canary sought out the Valiants. He found one particularly fine example in Sussex, New Jersey. Built in 1943, its shiny aluminum skin was as smooth as glass despite its years. He took off at 10:22 a.m. on August 19, 1968. It was a clear day, but clouds rolled in near Reading, Pennsylvania, followed by fog.

Apparently disoriented—people on the ground heard his plane circling—Canary flew straight into the thickly wooded slope of Blue Mountain, about 20 miles from Strausstown. Burning gas and oil drenched the grievously injured flyer as he struggled to pull himself out of the shattered greenhouse cockpit. He crawled on his hands and knees to a nearby cabin. In a daze, with much of his clothing burned away, he managed to tell the first rescuers what kind of plane it was, where he’d taken off from, and the unusual reason he was en route to California.

Canary suffered third-degree burns over 60 percent of his body, as well as deep cuts and internal injuries, and died three days later. Stories in the local newspapers all marveled that, in their corner of the world, a World War II–vintage plane being flown to Hollywood for use in an epic war movie had burst out of the clouds and into Blue Mountain.

“Jack was impatient,” Garrison recalled. “And in aviation, impatience gets you killed.”

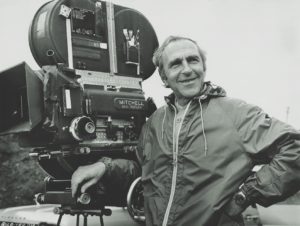

american half

The American sequences of Tora! Tora! Tora! were to be directed by Richard Fleischer, a respected and highly competent studio veteran with credits that included The Narrow Margin and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. He was known for bringing in taut productions on time and on budget. One could say that he’d been in the movies since before he was born: His father, Max Fleischer, was one of the industry’s earliest and most creative animators (he brought such characters as Betty Boop and Popeye to the screen), directors, and producers. But Richard Fleischer was hardly of the same stature as Kurosawa (who would later maintain that he was told that David Lean, who created Lawrence of Arabia among other expansive epics, would be his counterpart). And here the trouble began. Kurosawa saw Fleischer’s Fantastic Voyage and hated it. He met Fleischer and Williams in Hawaii, where he was alarmed by how much ketchup the American director poured on his food; from then on, he referred to Fleischer as “Ketchup Man.”

The battleship building and plane gathering paused for eight months as Fox delayed production in the face of increasing financial pressures. It wasn’t until December 1968 that shooting finally began on both sides of the Pacific—and literally on the Pacific, with the Yorktown takeoff sequence. While that footage turned out better than anyone had hoped, problems in Japan quickly multiplied. Kurosawa, it turned out, had hired business executives for major roles, including Yamamoto, on the theory that their serious demeanors would mimic those of naval admirals. (Fox executives suspected that he was lining up financiers for future films.)

The director seemed agitated and exhausted and behaved oddly on the set. Losing his temper with the man who snapped “the clapper” at the start of each scene, he hit the man with the script. The man quit. Soon after that, he ordered the crew to repaint a white room with another shade of white so similar that no one could tell the difference. When he discovered that the books in an admiral’s cabin were not ones the admiral would have read, he sent terrified crew members scouring bookstores for the correct volumes—even though they wouldn’t appear on camera. He bristled at Williams’s cost constraints and requests for updates. He wore a helmet for no apparent reason.

Panicked Telexes flew back and forth between Fox liaisons in Japan and the bosses in Hollywood. But the news just got worse. After three weeks, Kurosawa had shot only six minutes of film. And not surprisingly, the business executives turned out to be terrible actors.

Williams, realizing that he had to fire The Emperor, traveled to Japan to deliver the news in person. They met along with a pair of translators in a hotel room. Kurosawa, seemingly calm and cool behind his sunglasses, listened, paused, made a short statement, and then left. Williams asked what Kurosawa had just said and was mortified to learn that one of the world’s most famous directors had announced that he was going to return to his hotel and commit hara-kiri, Japanese ritual suicide.

He didn’t make good the threat right away. But in 1971, with his fortunes further declining, Kurosawa did indeed try to kill himself by slitting his wrists.

international fallout

Kurosawa’s firing was even bigger international news than his hiring. Darryl and Richard Zanuck were both furious when they realized that none of his footage appeared to be usable. In a father-and-son rage, they ordered the whole dual-production plan scrapped, insisting that Tora! become a strictly American story. But the equal involvement of the Japanese, for them to own their own story, had become an obsession for Williams. He begged his bosses to reconsider; after all, he argued, the giant sets had already been built in Japan, the crews hired, the contracts signed. That meant a lot of money would be thrown away, and for movie studio heads, few thoughts are more horrifying than that. Father and son relented.

But Williams had other problems. A 60 Minutes exposé revealed the involvement of Minoru Genda, the attack

planner, and the fact that the filmmakers had leased the USS Yorktown and other navy ships, manned by active-duty personnel, at a cost of nearly $300,000. Protests erupted objecting to the U.S. military participating in a movie recounting a great defeat, and the anger was only exacerbated by the controversy over the nation’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Fox took out full-page ads defending itself as Williams received death threats. Genda’s name was removed from the credits, although he continued to work on the project. The script was still too long, and the navy, which had script approval, objected to entire pages that made its officers look like bumbling oafs. Williams continued to cut back the script even as filming was underway.

Hiring a new director in Japan turned out to be a struggle, as no one wanted to offend Kurosawa. But with the clock ticking, Williams finally hired two: Toshio Masuda and Kinji Fukasaku. Masuda had trained as a kamikaze pilot during the waning days of World War II but was discharged, to his everlasting good fortune, for “antimilitary sentiment.”

The new directors brought in a new cast, including several highly regarded Japanese actors, among them So Yamamura to play Yamamoto and Eijiro Tono to play Admiral Chuichi Nagumo. They further trimmed Kurosawa’s script while keeping many of his scenes and lines as well as his sets. The directors, talented journeymen on a par with Fleischer, each spent a month working on the film; Fukasaku handled action scenes, and Masuda shot the interior sequences.

Finally, they shot the magnificent opening sequence on the Nagato. Busloads of college students were brought in to line the decks of the towering set. They were all paid extra to get military-style haircuts. Up they went, up to every outcropping of the great vessel, where they stared impassively out to sea with the wind tugging at their white tunics while the cameras rolled and a trio of modified AT-6 Texans shipped from the United States roared overhead.

logistics, logistics, logistics

With production ramping up on both sides of the Pacific, the challenging logistics of such an unwieldly, multinational project became clear. Japanese uniforms were shipped to Hawaii. An American liaison group was dispatched to Japan. New film shot on the beach in Kyushu was developed in Kyoto and then flown in reserved seats on Japan Air Lines to Hollywood.

Some of the footage gave Fleischer heartburn. Japanese actors overacted, following their own theatrical traditions. And Masuda and Fukasaku didn’t “cover” the scenes with shots from multiple angles to be edited later. This quirk was a holdover from making movies in Japan during the war, when film was scarce. Fleischer and his team were used to shaping their films with a great deal of post-filming editing—Williams, after all, was a veteran editor—and this required lots of footage from different angles. They couldn’t do much with the tiny pieces of celluloid that came from Japan. More Telexes flew across the Pacific asking that the Japanese actors tamp down their reactions and that the directors shoot every scene from multiple angles.

Giant model ships—some of them 40 feet long—were shot in cavernous tanks at the Fox ranch in Calabasas, California, using high-speed cameras to give the vessels lifelike heft. When the film was played back at the conventional 23 frames per second, the models were essentially moving in slow motion, creating the impression of realistic movements for both the vessels and the roiling ocean waves. Smaller models were used farther away from the camera to give the impression of distance, a trick called “forced perspective.” Detergent created the appearance of frothy whitecaps. Getting this effect just right involved lots of trial and error and lots and lots of detergent.

Variety and the Los Angeles Times chronicled every problem facing the film with seeming relish. But this only made the senior Zanuck more determined to complete the epic and show that he could still make an old-fashioned blockbuster. Some close to Zanuck feared he was showing the first signs of dementia.

The main event, of course, was filming the attack in Hawaii. To pull it off, the American production team had to treat each day as if it were fighting a real war. Fox leased a giant navy hangar on Ford Island in the middle of the harbor that still had bullet marks from the real attack. There, Garrison and his team worked on the flyable planes, as well as dozens of fiberglass replicas that would be lined up on the ground for the Japanese to strafe. Some had working engines. They purchased and restored practically every car of 1940s vintage on Oahu.

At a cost of $1 million, a full-size mockup of the stern of the battleship Arizona was built atop three barges.

When shooting began, the 47 pilots of the “Fox Air Force” gathered every morning in a briefing room on Ford Island to go over the day’s assignments. Behind them, a rising sun flag adorned the wall, an airman’s joke. After the briefings the pilots would attack Pearl Harbor all over again; for weeks in the spring of 1969 Oahu rumbled with explosions and shrieking aircraft. More than 100 giant smoke pots blackened the sky both to capture the scale of the mayhem and to hide structures that had been built after 1941. The local newspapers provided daily coverage. Airplane hangars that survived the actual attack were blown to bits in the re-creation.

“We were on this ship, firing machine guns, cursing and screaming,” recalled Charlie Picerni a novice stuntman who, in various scenes, was set on fire, catapulted 70 feet through the air off a burning ship into the also burning water, and chased down a runway by a careering fighter plane. “If you worked on this movie, you thought you were in World War II,” he recently recalled in a telephone interview. “This was real. There was no faking, no bullshit.”

cursed set or opportunity?

Then, as if to prove Picerni right, came another tragedy. Guy Strong, the pilot of a Val dive-bomber, stalled while practicing formation flying and sidewinded into a sugarcane field, cutting a long black groove in the bright-green terrain. He died instantly. A former navy pilot, Strong was buried at the National Cemetery in Punchbowl Crater on Oahu, near victims of the actual attack.

A. D. Flowers, a legendary special effects expert, was in charge of all the explosions. Tora! was by far his broadest canvas; he would use every ounce of creativity and imagination to recreate the attack. After a decadeslong career in Hollywood that began with him working as a gardener for MGM, Flowers was known as one of Hollywood’s best “powder men” for his prowess at creating explosions. His creativity knew no limits: In time he would design a pressurized vest that would, on command, burst open with blood-spurting bullet holes, and he would capture mass human suffering in movies like The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno. For Tora! he and his team invented something they called an Air Ram—a box of pressurized air that when stepped on could send a stuntman like Picerni flying into the air—and timed explosions to occur at the precise moment planes flew over, often just feet above the ground.

Accidents were put to good use. At one point, the landing gear of one of five B-17s used in filming got stuck in the up position. As the pilot circled to deplete his gas to eliminate the danger of a fire or explosion, cameras were set up to record the touchdown. The shrieking one-wheel belly-landing was used in the film.

One of the most intricate sequences involved Zeros strafing Wheeler Field as American P-40s tried desperately to get airborne and fight back. Flowers and Fleischer timed it to the split second, but no matter how hard you plan, when you are making a movie “practical,” reality can take over.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Movie people still marvel at this shot today. It was supposed to be simple: A life-size, radio-controlled mockup P-40 with a working engine would taxi down the runway and explode as it was strafed. The cameras, one of them 200 feet away, were encased in thick plywood. Just in case.

It started as planned, with the motorized mockup easing onto the runway as the the Texans-dressed-as-Zeros zoomed in. The P-40 picked up speed as planned, racing down the flight line, until it started to take off—something for which it had not been designed and which no one on the crew thought aerodynamically possible. Flowers hit the button to blow it up but the P-40 careened into a line of dynamite-filled P-40s, and Picerni and his buddies ran for dear life.

In the final cut you can see the stuntman run, fall, scramble on all fours and then get up and run some more, the flaming debris of the exploding planes literally feet away from him, heavy pieces of metal clanking to the asphalt all around. Genuine terror is evident in his every muscle movement and panicked backward glance.

Fleischer used this accident in the film—three times, from three different angles.

muted premiere

Tora! Tora! Tora! premiered in New York City and Tokyo on September 23, 1970. Its final cost: $25.5 million—two and-a-half times the original budget, making it the second most expensive film ever produced to that point (after Cleopatra). But the initial box office results were modest, the reviews mixed. An altered and lengthened version released in Japan—with the Japanese directors getting top billing—was a smash hit.

After so much media attention and anticipation and so much money spent, perhaps anything less than a huge success would have been seen as a failure. Some blame goes to the final product itself—many reviewers found the long windup to the attack tiresome—but some, too, must be laid on the times. With the Vietnam War at its height and the country riven by unrest, an epic movie about the nation’s greatest military defeat was understandably not a popular topic.

Zanuck, Williams, and the others conceived the movie in one era but finished it in another. Fox never recovered from the financial hit. In the aftermath, Zanuck fired his son before he himself was removed as chairman, and the studio era finally came to a close.

Fleischer, perhaps as payback for the “Ketchup Man” nickname, disparaged Kurosawa, saying in his memoir that the one scene Kurosawa shot that survived was “the worst scene in the picture.” He also claimed that the Nagato set had been pointed in the wrong direction and that Kurosawa failed to notice because he never visited the beach in Kyushu. Yet numerous photographs exist of the Japanese director stalking around the wooden battleship throughout construction. For his part, art director Tsukasa Kondo took home the Nagato steering wheel and made a coffee table out of it.

Tora! won an Academy Award for Powers’s special effects but was soon relegated to late-night airings on local television stations, its 3-to-1 Panavision aspect ratio cut by two-thirds—the left and right sides—to fit the small screen, with occasional panning within the frame to capture key images. But then, slowly, the film’s reputation grew. Fox sold the footage (to Fleischer’s further annoyance), and it appeared in productions ranging from Midway in the late 1970s to The Final Countdown in 1980, even to Australia in 2008. But its influence can be seen in far more films. The scene where those Zeros descend like huge dragonflies to attack Wheeler Field, for example, has been referenced in many other films, including the Star Wars saga.

product of its time

To this day, film historians marvel that a project like Tora! was even undertaken; no one tried anything like it ever again. Aviation afficionados consider it one of the greatest airplane movies ever made. Videos in letterbox formats restored the film to its intended widescreen glory, followed by increasingly ambitious DVD and Blu-ray releases, complete with all manner of commentaries, documentaries, and extras.

In time, Fox made a profit. Many of the planes still tour the country as part of airshows. Tourists at the memorial for the USS Arizona on Oahu were asked in the 1990s where they got their knowledge of the attack on Pearl Harbor. The top answer? Tora! Tora! Tora!

On first viewing, even today, the film is definitely unusual. The strict adherence to dialogue from real life creates a quasi-documentary feel. While the Japanese sequences have a staid, geometric elegance, some American sequences feel staged and wooden despite the efforts of such first-rate actors as Jason Robards (who was on Oahu on December 7, 1941), Martin Balsam, and Joseph Cotten. And despite all the effort, some historical inaccuracies crept in, like the Yorktown’s angled flight deck.

But on subsequent viewings, the movie develops a fascinating power. The absence of melodrama or any romantic subplots has allowed it to age well. The characters move forward—in a sense, all blindly—toward their fate, the increasing, even excruciating tension heightened by the back-and-forth editing between the two halves and the gorgeous, slowly building score by composer Jerry Goldsmith.

Kimmel is a victim; Yamamoto a tragic hero. There are screwups and missed opportunities on both sides—the Japanese, for example, fail to deliver their ultimatum on time because they don’t have a skilled typist. The “manning the rails” sequence on the Nagato is stunning—somehow all that wood looks like cold, riveted steel on film—as are the takeoff and the subsequent flight of Garrison’s and Canary’s strike force through the lush mountains of Oahu.

And then there’s the unspeakable horror of the attack itself—that smothering spectacle of death from above. The switch in mood from the buildup to the attack is jarring—but that’s how it was that morning in December 1941.

But the film’s greatest accomplishment might best be appreciated outside of movie theaters. Before it was made, and especially during the war itself, the Japanese were usually portrayed in American films as evil, duplicitous, and often incompetent, plotting their schemes behind bottle-glass spectacles. Tora! changed that. The Japanese were skilled, honorable military professionals here, wrestling with the horror that they were about to unleash, in charge of a skilled fighting force of awesome power—the Nagato was proof of that. And man, could they fly those planes. Subsequent war movies treated them similarly, right up to Clint Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima in 2008.

Such humanization of a modern enemy was a profound thing indeed. And perhaps that is Tora! Tora! Tora!’s enduring legacy. Though it failed in some ways as cinema, brought down careers, and led to at least two deaths, it succeeded where few other films have in putting our painful history in context and illuminating the humanity on both sides of the Pacific in World War II. MHQ

Wendell Jamieson, an award-winning reporter and editor, has worked for every major New York City newspaper, including, for 18 years, the New York Times. While at the Times he wrote occasionally about film, with a focus on Japanese cinema. He is the author of New York by New York (Assouline Publishing, 2018).

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.